This chapter discusses the results in the context of the research questions and the literature review. The opening section deals with the first research question, which focused on the differences between the autobiographical story and the ELEANITZ story in terms of comprehension. The second section discusses the differences between both stories in terms of raising interest and motivation among students, which relate to the second research question. The third section focuses on the differences in the use of English by the students on the questionnaires of both stories, linked with the third research question.

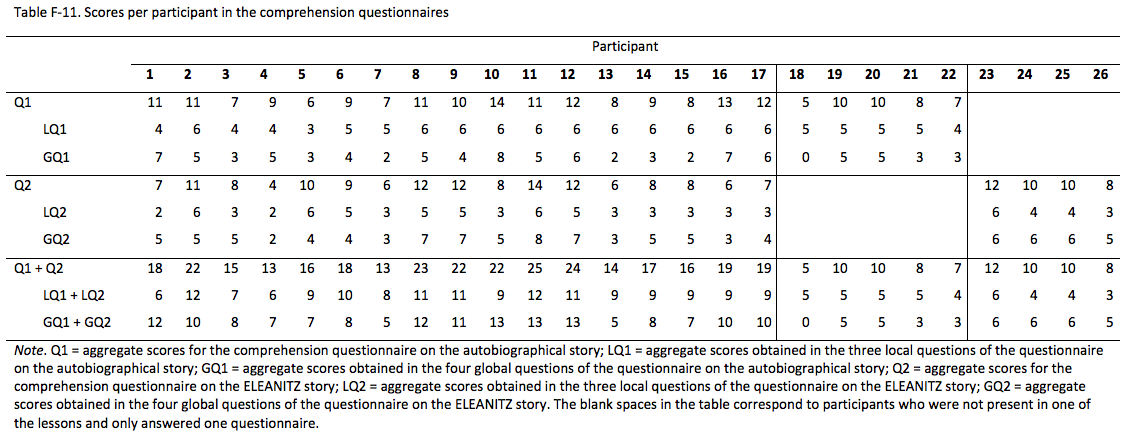

The scores of the comprehension questionnaires suggest that both stories were understood fully in some aspects, and partially in others. In particular, the autobiographical story was understood better than the ELEANITZ story, and the students had better understanding of the stories at the local level than they did at the global level, especially for the autobiographical story.

As regards the contradictory results of the local and global questions, they are in line with previous studies about the effects of question types on listening comprehension by EFL learners. For instance, while Shohamy and Inbar report higher scores for local questions, Park reports higher scores for global questions (G.-P. Park, 2004). Furthermore, a study on the relation between comprehension skill and inference making ability concludes that those who comprehend poorly can often answer local questions, but have difficulty integrating the text globally and selecting the relevant information to produce inferences (Cain, Oakhill, Barnes, & Bryant, 2001). Yet, it is beyond the scope of this study to analyse these issues in depth.

On the other hand, the differences in the scores of the comprehension questionnaires were not statistically significant, due to the small sample size. However, the effect size, that is, the magnitude of the difference between the comprehensions of the two stories, can be interpreted as being attributable to the differences between the two storytelling activities, following Hattie’s guidelines for educational contexts (2009), which establish that Cohen’s d > 0.40 should be interpreted as the method or intervention researched having desired effects. Thus, it could be argued that the difference in comprehension had practical significance in the context of education.

The initial objective of assessing the comprehension of both stories was to test if the autobiographical story had been adapted appropriately, by comparing it to a story within the ELEANITZ project. However, the higher comprehension scores obtained by the autobiographical story raise the question on why that happened, particularly bearing in mind that the readability test graded the autobiographical story as being more challenging than the ELEANITZ story. Yet, even if we leave the results of the local and global questions aside, the interpretation of the comprehension results is challenging for several reasons.

Firstly, it must be borne in mind that the absence of counterbalanced measures design in this study could have caused learning effect, thus allowing participants to improve scores in the questionnaire of the ELEANITZ story, which took place in the second lesson. This would be particularly true for global questions, as they were the questions that more doubts raised during the pre-task activity where the whole group, together with me, went through all the questions to clarify their meaning.

Secondly, my own involvement in the storytelling could have affected the results, as I could have inadvertently stressed the parts of the autobiographical story most relevant to the questions. I also told the autobiographical story with more passion than the CD recording did for the ELEANITZ story, and my motivation could have reflected on students’ achievement, as previous studies suggest (Dörnyei, 2001; M. J. Guilloteaux & Dörnyei, 2008). In addition, the novelty factor could have influenced the activities, as the two lessons on which the case study is based were the only activities led by me with this group of students during my school placement. Lastly, the two cameras that were set up to record the two lessons added to the excitement and caused short distractions to some of the students.

Thirdly, several variables that affect comprehension at the time of telling the story were different between the two stories:

- Characteristics of the input: the autobiographical story had repetition, comprehension checks and gestures, which improve comprehension (Peñate Cabrera & Bazo Martínez, 2001), but the storytelling was longer and had a more unfamiliar topic, with the opposite effect (Buck, 2001); text characteristics were also more complex in the autobiographical story, making comprehension more challenging (Buck, 2001; Révész & Brunfaut, 2013). Regarding the length of the story, even though the semi-scripted text of the autobiographical story had 562 words and the ELEANITZ story had 526, the storytelling took 11 minutes in the former, while the latter took 5 minutes and 40 seconds. The difference in length was mainly caused by rephrasing introduced to simplify grammar, repetitions, answers to clarification requests made by the students, and comprehension checks.

- Characteristics of the task: the autobiographical story consisted in a listening activity, whereas the ELEANITZ story was a simultaneous reading and listening activity, and the strategies used for comprehension in each case are different, leading to dissimilar comprehension scores (Lund, 1991; Vandergrift, 2007; Woodall, 2010). As a result, it is difficult to know which of the two stories might have had better conditions for comprehension regarding the task.

- Characteristics of the setting: there was considerably more background noise while the ELEANITZ story was played on the CD, and the quality of sound was poorer, which made comprehension more difficult.

Additionally, the possibility of students having copied cannot be discarded, since the original arrangement of grouped desks was maintained, although no clear evidence of this was found.

Finally, the fact that student engagement and motivation were higher for the autobiographical story could have also had a positive effect on the performance in the comprehension questionnaires, as previous studies report (Vandergrift, 2007).

Because of the large number of factors that were different in the two lessons, it is not possible to identify the exact elements or combination of elements that might have caused the autobiographical story to be comprehended better than the ELEANITZ story. Therefore, the first research question has been answered partially, as I found differences in terms of comprehension between the two stories, but the interpretation of the reasons for those differences remains inconclusive.

In the first place, the results show that the autobiographical story had the power to spark autobiographical stories in the participants, while the ELEANITZ story did not. Even in the little welcoming context of a written comprehension questionnaire, the students felt inclined to share their personal stories. Thus, it can be concluded that the results of this study conducted on primary students are in agreement with Kazuyoshi’s finding of autobiographical storytelling having a contagious effect on university students (2002).

As regards the reasons behind the results, the authenticity and truthfulness of the autobiographical story could have played an important role, bearing in mind that previous studies provide evidence on the importance of both features for student engagement and motivation (Dörnyei, 1994; Guariento & Morley, 2001; Leggo, 2007).

Additionally, although not all participants could be observed for on-task and off-task behaviour, the results show some off-task behaviour in the lesson on the ELEANITZ story, and virtually no off-task behaviour during the lesson on the autobiographical story. These results are consistent with those of previous studies that measured on-task and off-task behaviour when using artificial materials compared to authentic materials (Peacock, 1997). Thus, it can be claimed that the use of authentic materials had a positive effect on the level of interest, engagement and motivation experienced by the students.

Furthermore, the autobiographical stories written by the participants imply that they made close to literal connections with the stories that were told in the two lessons. As a result, their own autobiographical stories mostly shared the same setting (the mountains) and contained an identical element (an experience of risk, an incident) as the autobiographical story. Therefore, it can be argued that in order to echo personal stories among the participants, the story that was told to them needed to have a setting and a type of event that they were likely to have experienced themselves.

That fact could partly explain why the ELEANITZ story did not prompt any personal stories, as the probability of any of the students having been to the circus and being asked to take over the performers was very low. I believe that many of the students have probably replaced a teammate in a sports game, or a classmate in a school play, just like they must have felt a bit lost in their first encounters with EFL, like I did with Japanese in Japan, but they did not generalise or project the stories they were told that far.

Secondly, the autobiographical story was liked clearly better, mostly because it was found to be more interesting, but also because it evoked emotional bonds. Besides, in the few cases when the ELEANITZ story was preferred, it was mainly because it seemed easier.

However, it is interesting to notice that mainly high achievers in the comprehension questionnaires liked the ELEANITZ story better and found it easier. This could imply that they favoured the most familiar story, or that they felt more comfortable in the reading and listening activity, finding the autobiographical story more challenging.

As for the reasons why the participants found the autobiographical story more interesting and motivating, the results suggest that the autobiographical story contributed more to improve both intrinsic and extrinsic motivational factors reported by previous studies (Nicholson, 2013) in the participants, and it was a better source of engagement (J. C. Turner et al., 2014).

In particular, the participants themselves claimed that its contents were more interesting, which is known to increase intrinsic motivation (Nicholson, 2013). According to the criteria proposed by J.C. Turner et al. (2014), it can be argued that the autobiographical story also increased opportunities for belongingness and connectedness with others, since it provided favourable circumstances for a pleasant interaction and triggered personal stories in the participants. Likewise, the higher comprehension scores of the autobiographical story imply that it could have promoted feelings of competence in the students, thus improving their engagement.

On the other hand, my own motivation to tell a personal story could have also contributed to the autobiographical story raising more interest, engagement and motivation, as previous studies report (Dörnyei, 2001; M. J. Guilloteaux & Dörnyei, 2008).

Finally, the results should be interpreted with care, mainly because the sample was small. Thus, the study answered the second research question for the particular class that took part in the case study, but further research would be needed in order to generalise its results.

The subsample of the participants who answered the open-ended questions was small, and the results need to be interpreted with care. Hence, the study answered the third research question for the particular class that took part in the case study, but further research would also be needed in order to generalise its results.

The findings regarding the use of English in the answers suggest that the autobiographical story had more power to stimulate the use of English in primary students, in agreement with Kazuyoshi’s findings for university students (Kazuyoshi, 2002).

Most importantly from the practical point of view, it can be argued that mainly low achievers in the comprehension questionnaires were motivated during the lesson on the autobiographical story to use English in their explanations. This could have important practical implications, as generating willingness to communicate in L2 is most probably the most central objective of current foreign language pedagogy (Dörnyei, 2001).Continued on Next Page »

Ajayi, L. (2011). Video ‘Reading’ and Multimodality: A Study of ESL/Literacy Pupils’ Interpretation of Cinderella from Their Socio-Historical Perspective. The Urban Review, 44(1), 60–89. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11256-011-0175-0

Allen, D., & Tanner, K. (2006). Rubrics: Tools for Making Learning Goals and Evaluation Criteria Explicit for Both Teachers and Learners. CBE - Life Sciences Education, 5(3), 197–203.

Alley, D., & Overfield, D. (2008). An Analysis of the Teaching Proficiency Through Reading and Storytelling (TPRS) Method. In C. Wilkerson & C. M. Cherry (Eds.), Languages for the Nation. Dimension 2008. Selected Proceedings of the 2008 Joint Conference of the Southern Conference on Language Teaching and the South Carolina Foreign Language Teachers’ Association (pp. 13–25). Southern Conference on Language Teaching. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED503097

Andrade, H. G. (2005). Teaching with Rubrics: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. College Teaching, 53(1), 27–30.

Arter, J. (2000). Rubrics, Scoring Guides, and Performance Criteria: Classroom Tools for Assessing and Improving Student Learning. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New Orleans, LA. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED446100

Artigal, J. M. (1990). Uso-Adquisición de una Lengua Extranjera en el Marco Escolar Entre los Tres y los Seis Años. CL & E: Comunicación, Lenguaje y Educación, (7), 127–144.

Arzamendi, J., Etxeberria, J., Garagorri, X., Elorza, I., Ball, P., & Lindsay, D. (2003). A los 10 Años de Evaluación de la Experiencia Eleanitz-Inglés. Enseñanza-Aprendizaje de las Lenguas Extranjeras en Edades Tempranas, 143–174.

Azpillaga, B., Arzamendi, J., Etxeberria, F., Garagorri, X., Lindsay, D., & Joaristi, L. (2001). Preliminary Findings of a Format-Based Foreign Language Teaching Method for School Children in the Basque Country. Applied Psycholinguistics, 22(1), 35–44.

Birky, B. (2012). Rubrics: A Good Solution for Assessment. Strategies, 25(7), 19–21.

Boston, C. (2002). Understanding Scoring Rubrics: A Guide for Teachers. College Park, MD: ERIC Clearinghouse on Assessment and Evaluation. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED471518

Bromer, J. (1995). When I Was a Baby: Autobiographical Talk in a Preschool Classroom. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/eric/docview/62552414/abstract/E7835A1856E34006PQ/1?accountid=17248

Bryant, S. C. (2008). How to Tell Stories to Children and Some Stories to Tell. Tennessee: Dodo Press.

Buck, G. (2001). Assessing Listening. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press.

Bulger, M. E., Mayer, R. E., Almeroth, K. C., & Blau, S. D. (2008). Measuring Learner Engagement in Computer-Equipped College Classrooms. Journal of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia, 17(2), 129–143.

Cain, K., Oakhill, J. V., Barnes, M. A., & Bryant, P. E. (2001). Comprehension Skill, Inference-Making Ability, and Their Relation to Knowledge. Memory & Cognition, 29(6), 850–859.

Cenoz, J. (2011). The Increasing Role of English in Basque Education. English in Europe Today. Sociocultural and Educational Perspectives, 15–30.

Cenoz, J., & Etxague, X. (2011). Third Language Learning and Trilingual Education in the Basque Country. In S. Björklund & I. Bangma, Trilingual Primary Education in Europe: Some Developments With Regard to the Provisions of Trilingual Primary Education in Minority Language Communities of the European Union (pp. 32–44). Ljouwert/Leeuwarden: Fryske Akademy; Mercator Education.

Cheng, H.-F., & Dörnyei, Z. (2007). The Use of Motivational Strategies in Language Instruction: The Case of EFL Teaching in Taiwan. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 1(1), 153–174. http://doi.org/10.2167/illt048.0

Cheyney, D. A. (2010). The Use of Rubrics for Assessment of Student Learning in Higher Education (Doctoral Dissertation). Talbot School of Theology, Biola University, La Mirada, CA. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/eric/docview/860152539/abstract/E2CE33D7361F4D35PQ/10?accountid=17248

Ciampa, K. (2012). ICANREAD: The Effects of an Online Reading Program on Grade 1 Students’ Engagement and Comprehension Strategy Use. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 45(1), 27–59.

Crossley, S. A., Allen, D. B., & McNamara, D. S. (2011). Text Readability and Intuitive Simplification: A Comparison of Readability Formulas. Reading in a Foreign Language, 23(1), 84–101.

Crossley, S. A., Greenfield, J., & McNamara, D. S. (2008). Assessing Text Readability Using Cognitively Based Indices. TESOL Quarterly: A Journal for Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages and of Standard English as a Second Dialect, 42(3), 475–493.

Daniel, A. K. (2012). Storytelling across the primary curriculum. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon; New York: Routledge.

Davis, E. A., Beyer, C., Forbes, C. T., & Stevens, S. (2011). Understanding Pedagogical Design Capacity Through Teachers’ Narratives. Teaching and Teacher Education: An International Journal of Research and Studies, 27(4), 797–810.

De La Paz, S. (2009). Rubrics: Heuristics for Developing Writing Strategies. Assessment for Effective Intervention, 34(3), 134–146. http://doi.org/10.1177/1534508408318802

Desjardins, E. N. (2011). Small Stories for Learning: A Sociocultural Analysis of Children’s Participation in Informal Science Education (Doctoral Dissertation). Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, NY. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/eric/docview/1023531028/abstract/D5393755946543FEPQ/1?accountid=17248

Dewitz, P., Leahy, S. B., Jones, J., & Sullivan, P. M. (2010). The Essential Guide to Selecting and Using Core Reading Programs. Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Dörnyei, Z. (1994). Motivation and Motivating in the Foreign Language Classroom. Modern Language Journal, 78(3), 273–284.

Dörnyei, Z. (2001). New Themes and Approaches in Second Language Motivation Research. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 21(1), 43–59.

Dörnyei, Z., & Csizér, K. (1998). Ten Commandments for Motivating Language Learners: Results of an Empirical Study. Language Teaching Research, 2(3), 203–229. http://doi.org/10.1177/136216889800200303

Elkhafaifi, H. (2005). The Effect of Prelistening Activities on Listening Comprehension in Arabic Learners. Foreign Language Annals, 38(4), 505–513. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.2005.tb02517.x

Ellis, G., & Brewster, J. (Eds.). (1991). The Storytelling Handbook for Primary Teachers. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books Ltd.

Ellis, G., & Brewster, J. (2002). Tell it Again! The New Storytelling Handbook for Primary Teachers. Harlow: Penguin English.

Elorza, I. (2005). Ikastolen ‘Eleanitz’ Proiektua: Euskara Ardaztzat Duen Eleaniztasuna. Jakingarriak, (57), 22–27.

Elorza, I., Fano, D., & Tejada, E. (2005). Where’s the Magician?. Donostia: Ikastolen Elkartea.

Elorza, I., & Muñoa, I. (2008). Promoting the Minority Language Through Integrated Plurilingual Language Planning: The Case of the Ikastolas. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 21(1), 85–101. http://doi.org/10.2167/lcc345.0

Euskal Herriko Ikastola EKE (EHI EKE). (2013). Eleanitz Project. Retrieved 4 January 2015, from http://www.eleanitz.org/public/Eleanitz_Project

Fox, M. (2008). Reading Magic: Why Reading Aloud to Our Children Will Change Their Lives Forever (Updated end rev ed.). Orlando, Fla: Harcourt.

Fox, M. (2013). What Next in the Read-Aloud Battle? Win or Lose? The Reading Teacher, 67(1), 4–8. http://doi.org/10.1002/TRTR.1185

Freadman, A. (2014). Fragmented Memory in a Global Age: The Place of Storytelling in Modern Language Curricula. The Modern Language Journal, 98(1), 373–385. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2014.12067.x

Fritz, C. O., Morris, P. E., & Richler, J. J. (2012). Effect Size Estimates: Current Use, Calculations, and Interpretation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 141(1), 2–18. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0024338

Garagorri, X., Elorza, I., & Lindsay, D. (1997). ELEANITZ Eleaniztasuneko Proiektua, Ingelesa 4 Urtetik Aurrera Irakastea. Jakingarriak, 36, 30–39.

Garvie, E. (1990). Story as Vehicle: Teaching English to Young Children. Clevedon; Philadelphia: Multilingual Matters, Ltd.

Gipuzkoako Ikastolen Elkartea. (2009). Story Projects Tutorial. Story Projects 2. Teacher’s Guide.

Gobierno Vasco. Departamento de Educación, Universidad e Investigación. (2010). Decretos curriculares para la Educación Infantil, Básica y Bachiller en la Comunidad Autónoma del País Vasco. Retrieved from http://www.hezkuntza.ejgv.euskadi.net/r43-2459/es/contenidos/informacion/dig_publicaciones_innovacion/es_curricul/adjuntos/14b_curriculum/320002c_Pub_EJ_curriculum_basica_c.pdf

González Somocurcio, J. (2014). Eleanitz Proiektuak Dituen Hutsuneak. Irakaslearen ikuspegia (Undergraduate Dissertation). Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea - Universidad del País Vasco, Bilbao. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10810/14017

Guariento, W., & Morley, J. (2001). Text and Task Authenticity in the EFL Classroom. ELT Journal, 55(4), 347–353. http://doi.org/10.1093/elt/55.4.347

Guilloteaux, M.-J. (2013). Motivational Strategies for the Language Classroom: Perceptions of Korean Secondary School English Teachers. System: An International Journal of Educational Technology and Applied Linguistics, 41(1), 3–14.

Guilloteaux, M. J., & Dörnyei, Z. (2008). Motivating Language Learners: A Classroom-Oriented Investigation of the Effects of Motivational Strategies on Student Motivation. TESOL Quarterly: A Journal for Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages and of Standard English as a Second Dialect, 42(1), 55–77.

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible Learning: A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement. London; New York: Routledge.

Hegler, K. L. (2003). Using General Education Assessment Rubrics to Document Basic Skills and Content Knowledge. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New Orleans, LA. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED472812

Howe, A., & Johnson, J. (1992). Common Bonds: Storytelling in the Classroom. London: Hodder & Stoughton.

Hsiao-fang, C. (2004). A Comparison of Multiple-Choice and Open-Ended Response Formats for the Assessment of Listening Proficiency in English. Foreign Language Annals, 37(4), 544–555.

Ikastolen Elkarteko Eleanitz-Ingelesa Taldea. (2003). Eleanitz-English: Gizarte Zientziak Ingelesez. Bat: Soziolinguistika Aldizkaria, (49), 79–98.

Kazuyoshi, S. (2002). Contagious Storytelling. The Language Teacher, 26(Special Issue: The Narrative Mind), 15–25.

Keane, J. T. (2010). Student Multimedia Autobiographies: The Roles of Technology, Personal Narrative, and Signifying Practices (Doctoral Dissertation). University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/eric/docview/898324097/abstract/D07BEE47EFD84FB3PQ/1?accountid=17248

Kobayashi, M. (2012). A Digital Storytelling Project in a Multicultural Education Class for pre-Service Teachers. Journal of Education for Teaching, 38(2), 215–219. http://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2012.656470

Kohn, A. (2006). The Trouble With Rubrics. English Journal,High School Edition, 95(4), 12–15.

Kouame, J. B. (2010). Using Readability Tests to Improve the Accuracy of Evaluation Documents Intended for Low-Literate Participants. Journal of MultiDisciplinary Evaluation, 6(14), 132–139.

Kugelmass, J. W. (2000). Subjective Experience and the Preparation of Activist Teachers: Confronting the Mean Old Snapping Turtle and the Great Big Bear. Teaching and Teacher Education, 16(2), 179–194.

Lasagabaster Herrarte, D. (2011). Basque as a Minority Language and English as a Foreign Language: Are They Complementary Languages in the Basque Educational System? Annales-Anali Za Istrske in Mediteranske Studije, 21(1), 93–100.

Le Fevre, D. M. (2011). Creating and Facilitating a Teacher Education Curriculum Using Preservice Teachers’ Autobiographical Stories. Teaching and Teacher Education: An International Journal of Research and Studies, 27(4), 779–787.

Leggo, C. (2007). Writing Truth in Classrooms: Personal Revelation and Pedagogy. International Journal of Whole Schooling, 3(1), 27–37.

Liu, C.-C., Wu, L. y., Chen, Z.-M., Tsai, C.-C., & Lin, H.-M. (2014). The Effect of Story Grammars on Creative Self-Efficacy and Digital Storytelling. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 30(5), 450–464. http://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12059

Livingston, M. (2012). The Infamy of Grading Rubrics. English Journal,High School Edition, 102(2), 108–113.

Lund, R. J. (1991). A Comparison of Second Language Listening and Reading Comprehension. The Modern Language Journal, 75(2), 196–204. http://doi.org/10.2307/328827

McKendry, M. G., & Murphy, V. A. (2011). A Comparative Study of Listening Comprehension Measures in English as an Additional Language and Native English-Speaking Primary School Children. Evaluation & Research in Education, 24(1), 17–40. http://doi.org/10.1080/09500790.2010.531702

Meddings, L., & Thornbury, S. (2009). Teaching Unplugged. Dogme in English Language Teaching. Peaslake: Delta Publishing.

Menezes, H. (2012). Using Digital Storytelling to Improve Literacy Skills. In Proceedings of the International Association for Development of the Information Society (Iadis) International Conference on Cognition and Exploratory Learning in Digital Age (Celda) (Madrid, Spain, October19-21, 2012). Madrid, Spain: International Association for the Development of the Information Society. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED542821

Mertler, C. A. (2001). Designing Scoring Rubrics for Your Classroom. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 7(25).

Morgan, G. L. (2008). Improving Student Engagement: Use of the Interactive Whiteboard as an Instructional Tool to Improve Engagement and Behavior in the Junior High School Classroom (Doctoral Dissertation). Liberty University, Lynchburg, VA. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1140&context=doctoral&sei-redir=1&referer=http%3A%2F%2Fscholar.google.es%2Fscholar%3Fhl%3Den%26q%3Dstudent%2Bengagement%2Bchecklist%26btnG%3D%26as_sdt%3D1%252C5#search=%22student%20engagement%20checklist%22

Morgan, J. (1983). Once Upon a Time: Using Stories in the Language Classroom. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press.

Moskal, B. M. (2000a). Scoring Rubrics Part I: What and When. ERIC/AE Digest. ERIC Digests. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED446110

Moskal, B. M. (2000b). Scoring Rubrics: What, When and How? Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 7(3). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/eric/docview/62234228/E2CE33D7361F4D35PQ/34?accountid=17248

Moskal, B. M. (2003). Developing Classroom Performance Assessments and Scoring Rubrics - Part II. ERIC Digest. ERIC Digests. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED481715

Msila, V. (2011). Autobiographical Narrative in a Language Classroom: a Case Study in a South African School. Language and Education, 26(3), 233–244. http://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2011.636820

Nicholson, S. J. (2013). Influencing Motivation in the Foreign Language Classroom. Journal of International Education Research, 9(3), 277.

Panadero, E., & Jonsson, A. (2013). The Use of Scoring Rubrics for Formative Assessment Purposes Revisited: A Review. Educational Research Review, 9, 129–144. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2013.01.002

Paran, A., & Watts, E. (Eds.). (2003). Storytelling in ELT. Whitstable: IATEFL.

Park, G. (2011). Adult English Language Learners Constructing and Sharing Their Stories and Experiences: The Cultural and Linguistic Autobiography Writing Project. TESOL Journal, 2(2), 156–172.

Park, G.-P. (2004). Comparison of L2 Listening and Reading Comprehension by University Students Learning English in Korea. Foreign Language Annals, 37(3), 448–458.

Peacock, M. (1997). The Effect of Authentic Materials on the Motivation of EFL Learners. ELT Journal, 51(2), 144–156. http://doi.org/10.1093/elt/51.2.144

Peñate Cabrera, M., & Bazo Martínez, P. (2001). The Effects of Repetition, Comprehension Checks, and Gestures, on Primary School Children in an EFL Situation. ELT Journal, 55(3), 281–288. http://doi.org/10.1093/elt/55.3.281

Pennac, D. (2008). Como una Novela (12th ed.). Barcelona, Spain: Anagrama.

Petit, S., Mougenot, C., & Fleury, P. (2011). Stories on Research, Research on Stories. Journal of Rural Studies, 27(4), 394–402.

Pilon, E. M. (1993). Autobiography and Writing Across the Curriculum: Bringing ‘Life’ to Disciplinary Writing (p. 24). Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Conference on College Composition and Communication, San Diego, CA. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/eric/docview/62772270/abstract/27539FC981C048E9PQ/1?accountid=17248

Quackenbush, J. L. (2010). Writing (and Re-Writing) a Gendered Educational Life: Envisioning Possibilities for Teachers’ Autobiographical Texts (Doctoral Dissertation). Columbia University, New York, NY. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/eric/docview/881461769/abstract/2A8F1D52FB314668PQ/1?accountid=17248

Read, C. (2007). 500 Activities for the Primary Classroom. Immediate Ideas and Solutions. Oxford: Macmillan Education.

Reason, P., & Bradbury-Huang, H. (2001). Introduction: Inquiry and Participation in Search of a World Worthy of Human Inspiration. In P. Reason & H. Bradbury-Huang (Eds.), Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice (pp. 1–13). London; Thousand Oaks, Calif: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Révész, A., & Brunfaut, T. (2013). Text Characteristics of Task Input and Difficulty in Second Language Listening Comprehension. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 35(1), 31–65. http://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0272263112000678

Rivera Maulucci, M. S. (2011). Language Experience Narratives and the Role of Autobiographical Reasoning in Becoming an Urban Science Teacher. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 6(2), 413–434.

Rossiter, M. (2002). Narrative and Stories in Adult Teaching and Learning. ERIC Digest. ERIC Digests, 4.

Rossiter, M., & Clark, M. C. (2007). Narrative and the Practice of Adult Education. Malabar, FL: Krieger Publishing Company.

Rubin, J. (1994). A Review of Second Language Listening Comprehension Research. The Modern Language Journal, 78(2), 199–221. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1994.tb02034.x

Savvidou, C. (2010). Storytelling as Dialogue: how Teachers Construct Professional Knowledge. Teachers and Teaching, 16(6), 649–664. http://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2010.517682

Schmidt, M., & Knowles, G. J. (1994). Four Women’s Stories of ‘Failure’ As Beginning Teachers. (p. 40). Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New Orleans, LA. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/eric/docview/62708098/abstract/7F3F302A8BBA48C1PQ/1?accountid=17248

Scrivener, J. (1994). Learning Teaching: a Guidebook for English Language Teachers. Oxford: Heinemann.

Taeschner, T., Gheorghiu, I., & Colibaba, A. (2013). ‘The Narrative Format’for Learning and Teaching Languages to Children and Adults. Synergy, (2), 223–235.

Taguchi, K. (2006). Is Motivation a Predictor of Foreign Language Learning? International Education Journal, 7(4), 560–569.

Thornbury, S. (2001). Point and Counterpoint. The Unbearable Lightness of EFL. ELT Journal, 55(4), 391–396. http://doi.org/10.1093/elt/55.4.391

Turner, J. C., Christensen, A., Kackar-Cam, H. Z., Trucano, M., & Fulmer, S. M. (2014). Enhancing Students’ Engagement Report of a 3-Year Intervention With Middle School Teachers. American Educational Research Journal, 51(6), 1195–1226. http://doi.org/10.3102/0002831214532515

Turner, M. (1996). The Literary Mind. New York: Oxford University Press.

Vandergrift, L. (2005). Relationships Among Motivation Orientations, Metacognitive Awareness and Proficiency in L2 Listening. Applied Linguistics, 26(1), 70–89. http://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amh039

Vandergrift, L. (2007). Recent Developments in Second and Foreign Language Listening Comprehension Research. Language Teaching, 40(3), 191–210.

Walters, L. M., Green, M. R., Wang, L., & Walters, T. (2011). From Heads to Hearts: Digital Stories as Reflection Artifacts of Teachers’ International Experience. Issues in Teacher Education, 20(2), 37–52.

White, B. F. (1995). Effects of Autobiographical Writing before Reading on Students’ Responses to Short Stories. Journal of Educational Research, 88(3), 173–184.

Whittaker, C. R., Salend, S. J., & Duhaney, D. (2001). Creating Instructional Rubrics for Inclusive Classrooms. Teaching Exceptional Children, 34(2). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/eric/docview/1437904047/abstract/E2CE33D7361F4D35PQ/31?accountid=17248

Wilson, D. E. (1993). Composing Experience and Knowledge: Narrative as a Critical Instrument in English Teacher Preparation. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the National Council of Teachers of English, Pittsburgh, PA. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/eric/docview/62797112/abstract/6E90A3610CDE429EPQ/1?accountid=17248

Woodall, B. (2010). Simultaneous Listening and Reading in ESL: Helping Second Language Learners Read (and Enjoy Reading) More Efficiently. TESOL Journal, 1(2), 186–205. http://doi.org/10.5054/tj.2010.220151

Wright, A. (1995). Storytelling With Children. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wu, R. (1994). ESL Students Writing Autobiographies: Are There Any Connections? Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Rhetoric Society of America, Louisville, KY. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/eric/docview/62702220/abstract/9C6FA8564B3F4EB8PQ/1?accountid=17248

Yoshina, J. M., & Harada, V. H. (2007). Involving Students in Learning Through Rubrics. Library Media Connection, 25(5), 10–14.

Zamanian, M., & Heydari, P. (2012). Readability of Texts: State of the Art. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 2(1), 43–53.

Zaro, J. J., & Salaberri, S. (1995). Storytelling. Oxford: Heinemann.

Zeleke, A. S. (2013). Does Viewing Test Items at Different Times Matter in English for Academic Purpose Listening Test? Modern Journal of Language Teaching Methods, 3(2), 63–77.

Appendix A – Key new vocabulary in the stories

This appendix contains the key vocabulary in each story that the participants were likely to encounter for the first time. The prelistening phase introduced the key vocabulary.

Key vocabulary that was addressed in the prelistening phase of the autobiographical story: hiking, mountain range, tent, hut, sleeping bag, bunk beds, onigiri.

Key vocabulary that was addressed in the prelistening phase of the ELEANITZ story: magician, magic show, MC (master of ceremonies), worried, orchestra, audience, circus, clowns, jokes, troupe.

Appendix B – The autobiographical story

Hiking in Japan

A few summers ago, my husband and I spent six weeks in Japan, one of them hiking in the Japanese Alps, a long mountain range about 3,000 metres high.

The day before we started hiking, we prepared our rucksacks and filled them with all the things we would need: the tent, our sleeping bags, the little stove, water bottles, a bit of cutlery, the rain jackets, a few spare clothes, a bit of soap and our toothbrushes. And, of course, we needed food.

So, we went to the supermarket. Unfortunately, we spoke only a few words of Japanese, we couldn’t read anything, and we found nobody who spoke English. Everything looked very unfamiliar to us in the supermarket. We needed to take some sandwiches for lunch. But, guess what? Japanese people don’t eat bread, so we had to find something else. The closest thing to sandwiches is onigiri, rice balls. So, we bought onigiri and some cakes. My husband said: “I hope the mountain huts along the path will sell food. Otherwise, we will have to come down in two days, instead of seven.”

The next day we started hiking for seven days in the Japanese Alps. The first day was the hardest, because we had to climb almost 2,000 metres. We couldn’t read Japanese maps or signs, so we weren’t sure if we would find the path easily. Luckily, the path was very clear, so we didn’t get lost.

On this first day, we found a small mountain hut that sold food, where other Japanese hikers were buying noodles and onigiri. So, I thought: “Food will be easy to get along the way.”

Most days we slept in our tent, close to other hikers. We all got up at the same time in the morning, then started walking at a different pace, and we met again in the evening on the next campsite. So, they were our “tent-neighbours,” and we became friends with two of them, even if we couldn’t speak Japanese, and they didn’t speak English.

One afternoon, it started to rain, so we decided to go to a mountain hut, instead of sleeping in the tent. We had a nice supper, and slept on bunk beds. The next morning, we saw that the workers in the mountain hut were very nervous, walking up and down and talking on the radio. Finally, some other hikers came carrying on their shoulders a man who looked sick; his face was blue. His friends told us with signals that he had a heart attack. Then, we heard a helicopter, and we realised that it was coming to rescue the sick man. A man was dropped from the helicopter with a cable, he tied the sick man, and both of them were lifted up with the cable again.

After the rescue, it was sunny again. We left the mountain hut and continued with our walk. When we got to the next campsite, we met our two friends. That night we had dinner together, and we shared their barbeque meat and our onigiri, together with some sake they had. It was their last night in the Japanese Alps, and the same for us.

The next day we walked down another 2,000 metres, and said goodbye to our Japanese friends. I never learned their names, but we were friends for seven days.

Appendix C – Criteria followed to adapt input and to design the comprehension questionnaires

Listening comprehension is a very complex process. Much of its details remain unknown and, consequently, assessing it is also difficult. An effort was made to shape the autobiographical story in such a way that its degree of difficulty would be equal to that of the ELEANITZ story.

Nevertheless, the circumstances under which the empirical research took place made it impossible to take into account all the factors that could have been addressed (Révész & Brunfaut, 2013; Rubin, 1994) if there had been more time to analyse the degree of difficulty of the ELEANITZ story and adapt the autobiographical story to match it.

On the other hand, although the level or degree of difficulty of the listening activity will be set by the task itself, and not the material (Guariento & Morley, 2001; Scrivener, 1994; Wright, 1995), some of the factors determining task difficulty are related to text characteristics. In general, complexity of the language, cognitive load and performance conditions are considered the factors that should receive special attention in this sense (as cited in Guariento & Morley, 2001).

Regarding text difficulty, the following guidelines were taken into account to set the complexity of the language and the cognitive load in order to make input more comprehensible in the autobiographical story (Buck, 2001; Ellis & Brewster, 2002; Révész & Brunfaut, 2013; Rubin, 1994):

- Unfamiliar words were avoided, using more high-frequency vocabulary whenever it was deemed suitable, and idioms and keywords that might be unfamiliar were introduced before telling the story. Redundancy of words new to listeners was used throughout the narration.

- Regarding verb tense, the simple past was used. Structures were kept simple, and sentences short.

- Story events were referred in chronological order, following a linear order. In addition, wherever necessary, the sequence of events was reinforced using appropriate transition words (first, then, before etc.). Transition words were used to improve cohesion. Direct speech was used when it was thought it would make the story easier to follow. Finally, the number of events and people in the story was kept short.

- Additionally, while telling the story, visual aid was used to provide a schema-based approach and students were encouraged to ask for further clarification whenever they did not understand something in the story, in order to promote the negotiation of comprehensible input along the storytelling.

The comprehension questionnaires for the two stories were designed following the extensive analysis on listening assessment carried out by Buck (2001) and the review of further research literature on the subject published later on (Vandergrift, 2007). The following criteria were taken into account to design the comprehension questionnaires concerning task difficulty (Buck, 2001):

- The amount of information to be processed.

- The location of the information to be processed within the text, as integrating scattered information is more difficult.

- The type of content to be produced, as recalling literal content is easier than summarising.

- The relationship between the order of the questions and the order of the information in the story, because the task is easier when both are the same.

- The order of the questions in relation to their difficulty, as the task is easier when the questions are arranged starting from the easiest and progressing to the most difficult.

Appendix D – The questionnaires and the post-test survey

1. The autobiographical story

Set of questions regarding the autobiographical story:

- Whom did Miren go hiking with in the Japanese Alps?

- Her Japanese friend

- Her husband

- Her brother

- Her neighbour

- Which of the following did Miren put in her rucksack?

- A stove, a rain jacket, some deodorant

- Sunglasses, a tent, a bit of soap

- A water bottle, a hat, some spare clothes

- A sleeping bag, some cutlery, a toothbrush

- How much did Miren climb on her first day in the Japanese Alps?

- 1 000 metres

- 2 000 metres

- 3 000 metres

- 4 000 metres

- What was the story about?

- It was about the different types of food in Japan

- It was about the friends Miren made in Japan

- It was about Miren’s holidays in Japan and what happened to her in the Japanese Alps

- It was about a man who had a heart attack and had to be rescued in a helicopter

- Where did Miren get the food she ate during her days in the Japanese Alps?

- She bought everything in the supermarket

- She always ate in the mountain huts

- She got part in the supermarket and part in the mountain huts

- She got part in the supermarket, part in the mountain huts and part from her Japanese friends

- After having listened to this story, if you went to the Japanese Alps, which would be the most important three things you would put in your rucksack?

- A sleeping bag, a rain jacket and a bit of food

- A lot of food, some spare clothes and a toothbrush

- A tent, a sleeping bag and some soap

- A water bottle, some cutlery and a stove

- What do you think is the message of this story, the reason why Miren chose it? Why do you think that?

- Does this story remind you of anything that happened to you? Explain what happened shortly, please.

2. The story “Where's the magician?”

Set of questions on the story “Where's the magician?”:

- How did Peggy find out about the show of the Tilly Troupe?

- Her mum heard it on the radio

- Peggy read it on the school magazine

- Her mum read it on the newspaper

- David told Peggy about it

- Who called whom to go to the Tilly Troupe’s show?

- First, Peggy called David. Then, David called all the others

- Peggy’s mum called all her friends

- First, David called Peggy. Then, Peggy called all the others

- First, Peggy called David. Then, each called two friends

- When was the show going to start?

- At a quarter to five

- At five o’clock

- At a quarter past five

- At half past five

- Choose the sentence which best summarises the story

- The story was about a magician who got lost and didn’t arrive on time for the show

- The story was about Peggy and her friends, and what happened to them when they went to see the Tilly Troupe’s show

- The story was about Peggy and her friends, and how they organised to go to a show

- The story was about the clowns Coco and Jolly, who were making jokes and got cross in the end

- What had the Tilly Troupe planned to do in the show?

- The Tilly Troupe had planned to do magic tricks, clown jokes, and singing and dancing

- The Tilly Troupe had planned to play with the orchestra and dance

- The Tilly Troupe had planned to do horse riding tricks

- The Tilly Troupe had planned to do some clown jokes and magic tricks

- After having listened to this story, if you wanted to go to the Tilly Troupe’s show, what are the most important 3 things you would do before:

- Phone a friend, buy a ticket, and learn a joke

- Read the newspaper, arrive on time for the show, and learn a song

- Buy a ticket, arrive on time for the show, and learn a card trick

- Learn a card trick, a song and a joke

- Do you think the story is believable? Why do you think that?

- Has anything similar ever happened to you? Explain what happened shortly, please.

3. The post-test survey

- Which story did you like more?

- The story about Miren hiking in Japan

- “Where's the magician?”

- If your regular teacher, Idoia, asked you to summarise one of the stories in class, which would you choose? Why?

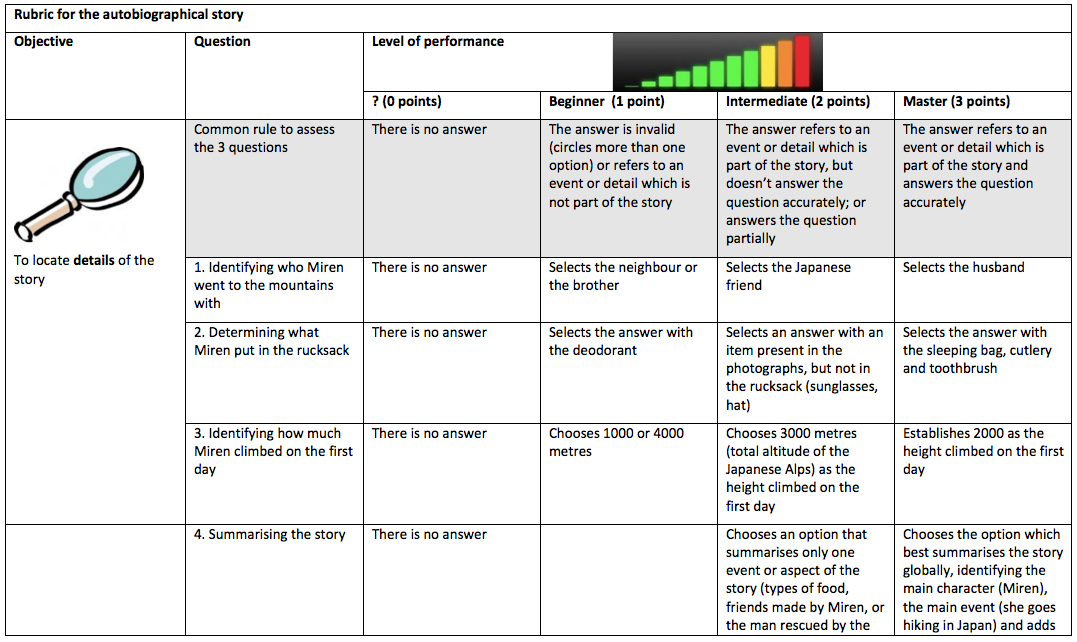

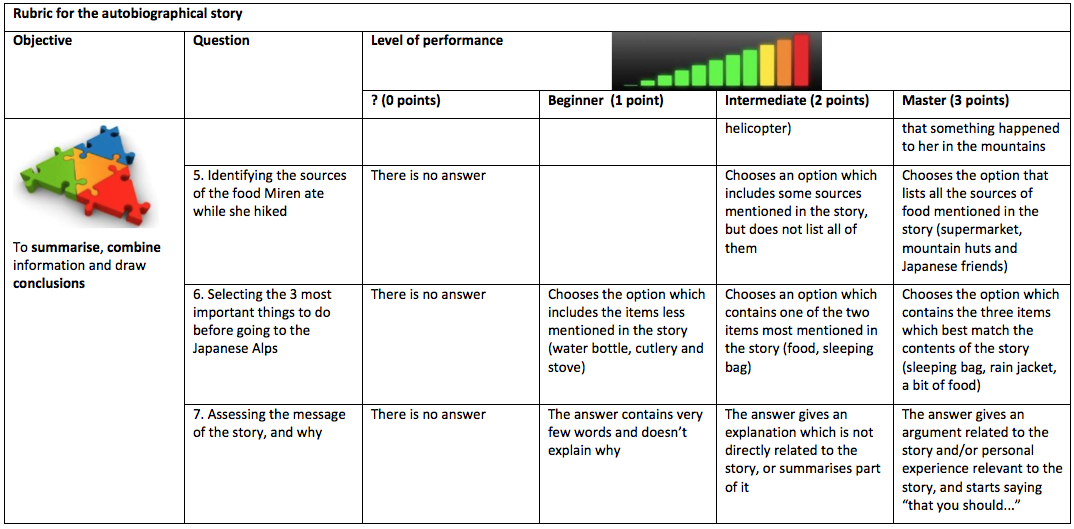

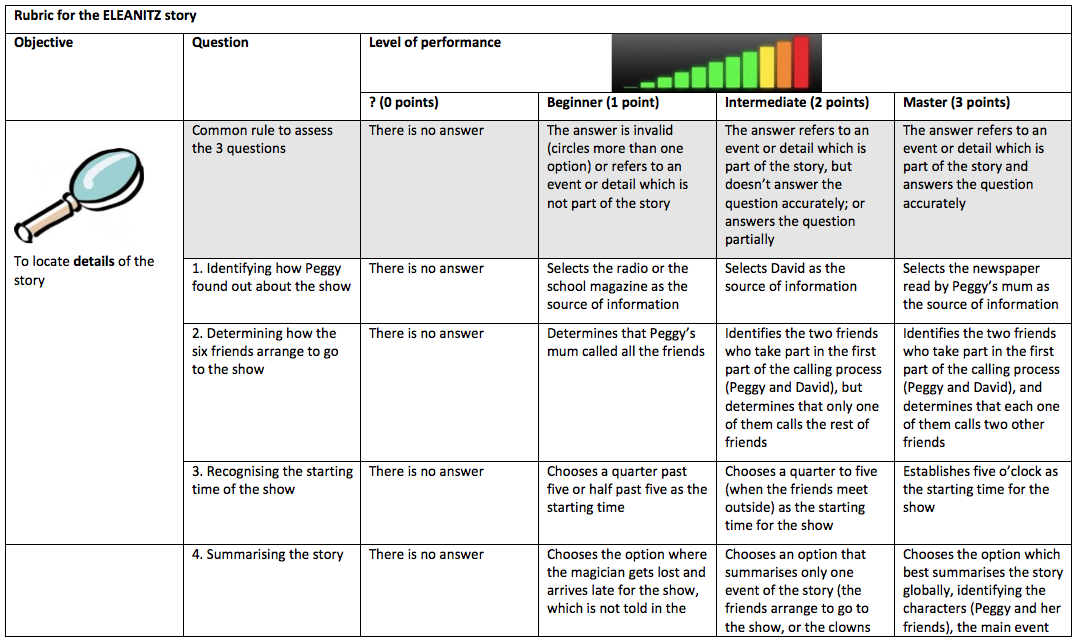

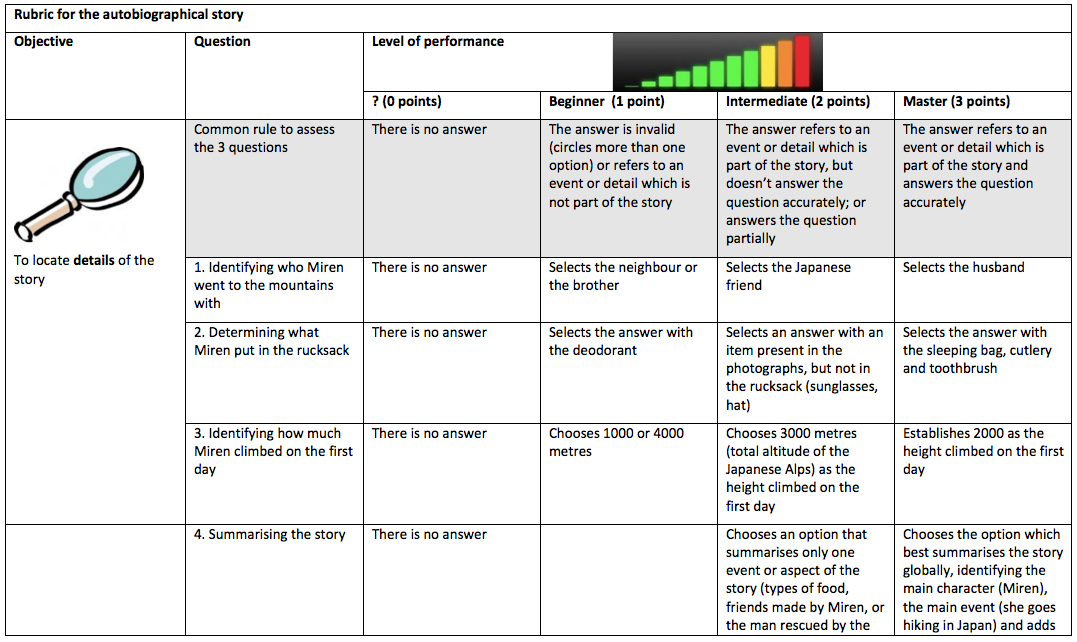

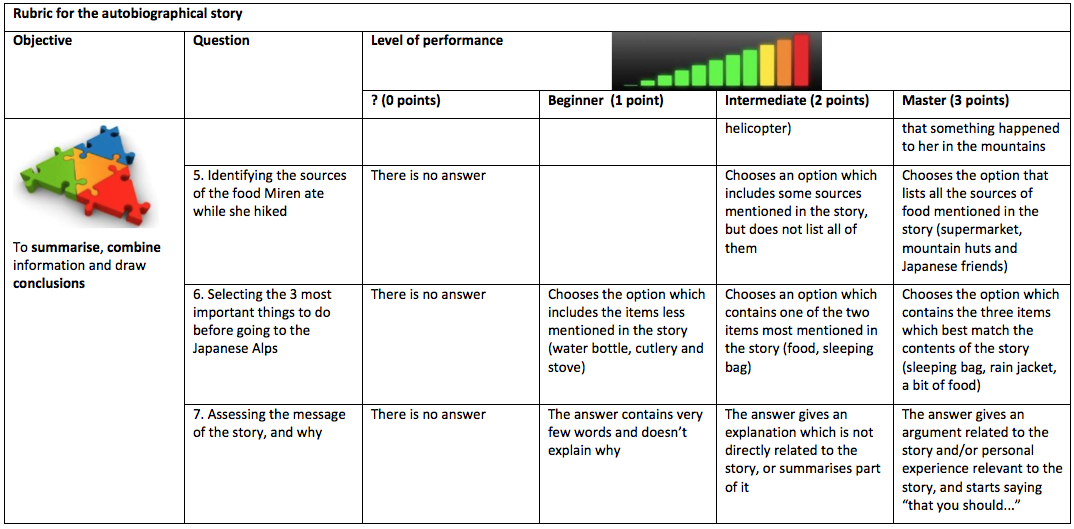

Appendix E – The Rubrics

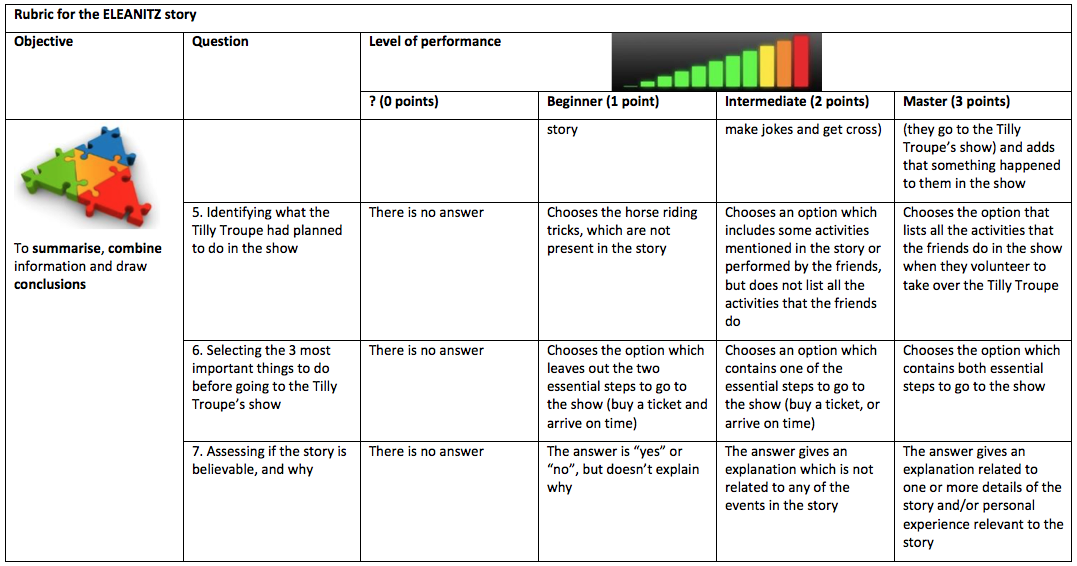

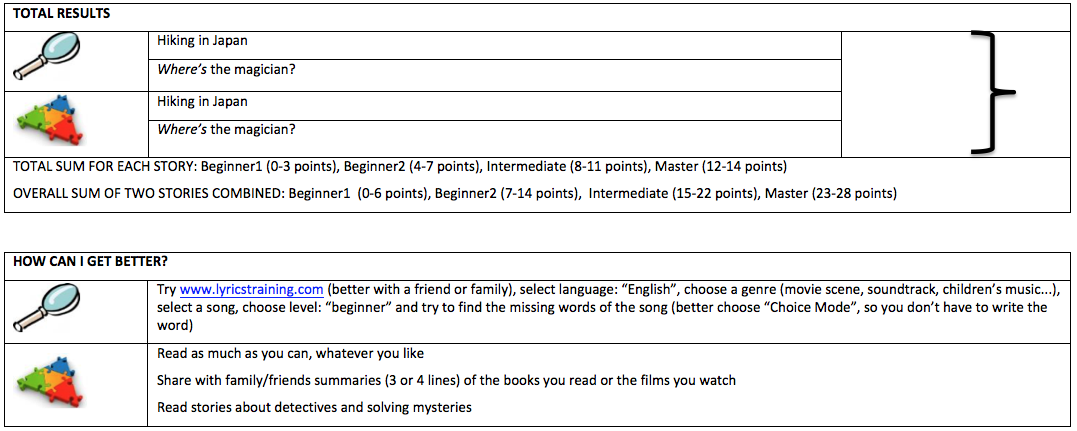

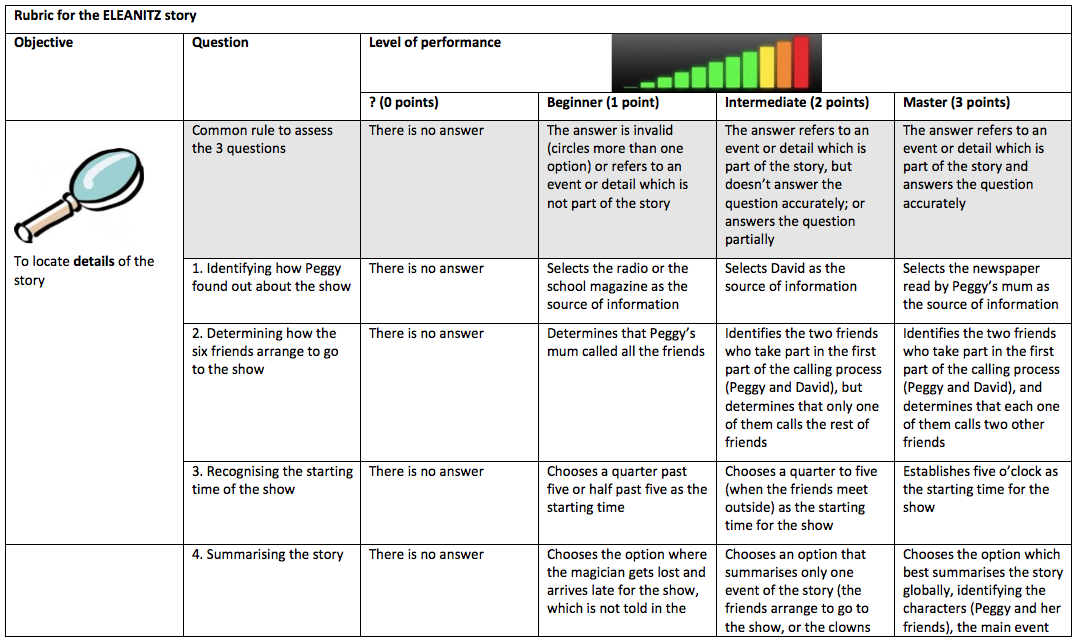

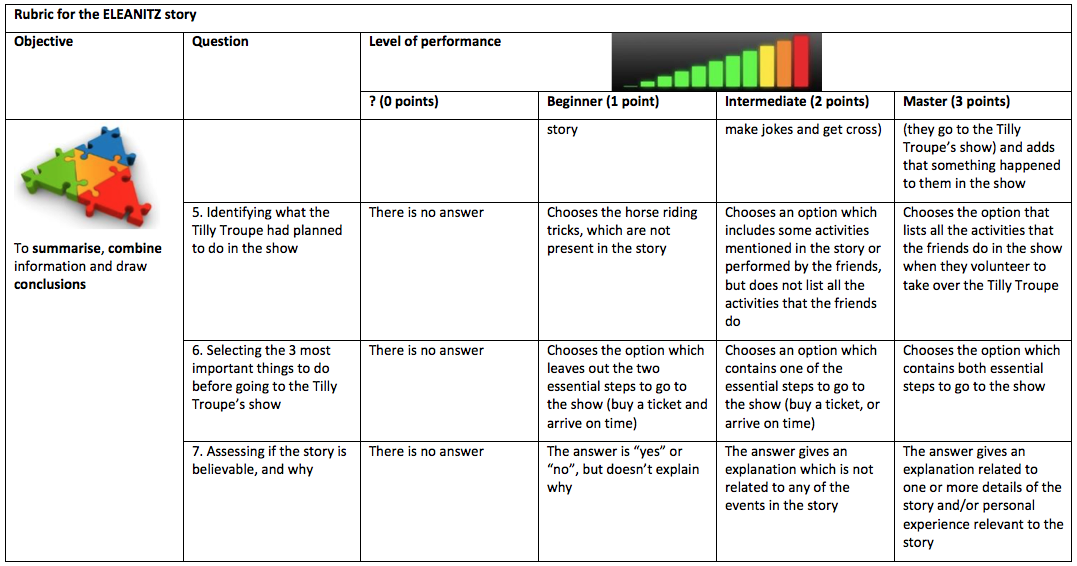

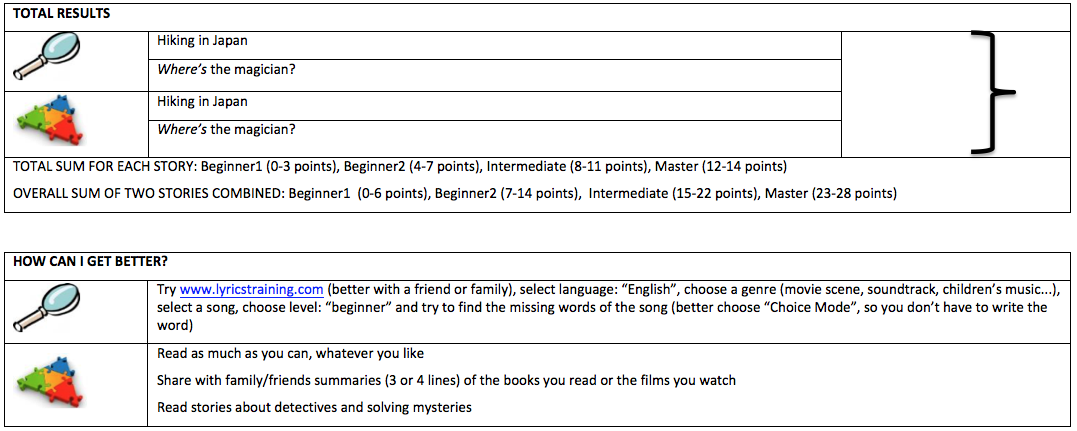

This case study met two important criteria which supported using a rubric as the assessment tool for the comprehension questionnaires (Allen & Tanner, 2006; Andrade, 2005; Arter, 2000; Moskal, 2000a; Panadero & Jonsson, 2013): it dealt with a complex process – listening comprehension – which demanded a qualitative approach in the assessment, and it was intended to give the participants feedback on the results of the questionnaires in the form of a formative assessment, which would give them some guidance as to how to improve their listening comprehension. Rubrics are widely used in all stages of education, and they are not free of controversy, having both detractors (e.g. Kohn, 2006) and advocates (e.g. Livingston, 2012).

The rubric was partially designed in the form of an instructional rubric (Andrade, 2005; Whittaker et al., 2001). Unfortunately, the circumstances of the case study forced to use it as a scoring rubric.

The three local questions of each questionnaire were assessed with a holistic rubric, while the analytic rubric was considered more adequate to assess the four global questions, as each one of them dealt with a different aspect of comprehension. For the purpose of giving feedback to the participants, the rubric was slightly changed, in order to make it more self-explanatory. In particular, the holistic section of the rubric, which is applied to the first three questions, was turned into an analytic rubric. Besides, the language used in the rubric was reviewed in an attempt to bring it closer to student language, as suggested by Whittaker at al. (2001) and images were introduced to help communicate the contents.

The following pages contain the final rubrics, completely analytic and adapted in order to be handed out to the participants as feedback on the activities.

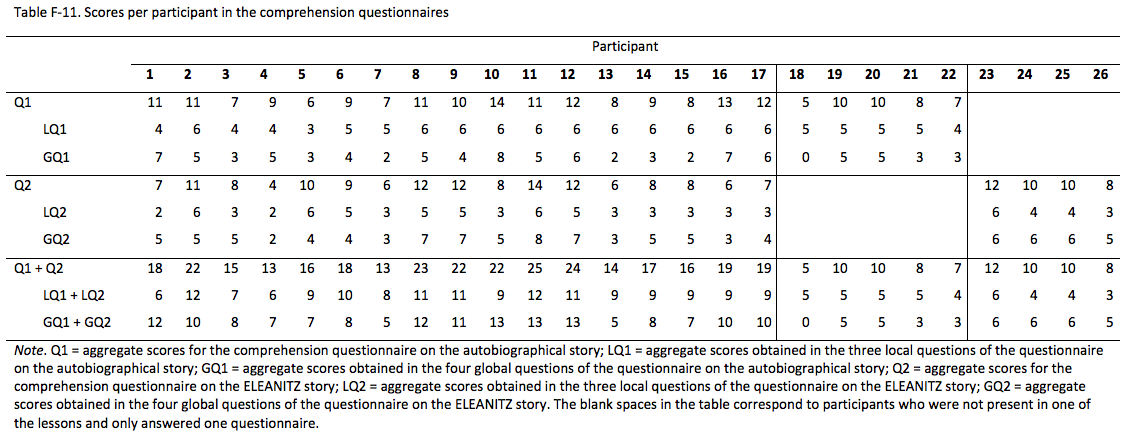

Appendix F – Comprehension scores per participant

The table in the following page shows the scores obtained by each participant in both stories.