The empirical evidence in this dissertation has been drawn from a case study involving a group of fourth grade primary students (aged 9 to 10) who took part in two storytelling activities held on different lessons; one being a listening activity, and the other being a listening and reading activity.

The first activity consisted in listening to an autobiographical story on my favourite hobby told by myself using several A3 size colour images as visual support. The second activity consisted in listening to an ELEANITZ story on a CD recording, for the first time, while students read it on individual copies of the storybook. The storybook (Elorza, Fano, & Tejada, 2005) combines text and colour illustrations in all pages.

The main methodological limitations of this study, namely the size of the sample, the use of convenience sampling, the differences in the conditions for the storytelling of both stories, and the absence of counterbalancing measures relate to aspects explained in section 1.1, which outlines the context of the study.

The participants were a class in the fourth grade of primary (children aged 9 to 10) at Astigarragako Herri Eskola (Gipuzkoa, Spain). There were 26 students in the class, 13 girls and 13 boys. Some students were ill on the days when the two stories were told. As a result, 22 students took part in the autobiographical storytelling (11 girls and 11 boys), and 21 took part in the ELEANITZ storytelling (10 girls and 11 boys). Overall, 17 took part in both activities, 5 took part only in the first one, and 4 took part only in the second one.

This group of students was selected through convenience sampling among the several groups of students whose EFL lessons I attended regularly during my 12-week school placement. An additional criterion taken into account for selecting the sample was the potential interest towards autobiographical stories. During this school placement, I took part in EFL lessons for two EYFS grades and three primary grades. The primary grades involved children aged 6 to 7, 7 to 8 and 9 to 10 respectively. The latter showed greater interest by far in personal stories concerning the EFL teacher and myself, and were therefore selected for the sample.

Regarding the level of proficiency in English, the sample had an additional degree of diversity beyond what would be expected in any Basque school, where some students start taking extra English lessons outside school as early as the beginning of primary. The EFL teacher reported that there were great disparities in the proficiency level within the group, as three or four students barely met the most basic objectives, and were a great distance away from those classmates who took extra English lessons outside school.

There are additional factors that need to be taken into account concerning diversity within the sample. Firstly, one of the students, who joined the group on the previous academic year, was in the Language Reinforcement Programme, as her L1 was Spanish and she had had no previous contact with either Basque or English before. Secondly, another student had dyslexia and received support from a Special Educational Needs teacher at school. Lastly, another student had joined the group two academic years before, showed signs of deep disengagement at school in all subjects, and was under study to assess if support needed to be given to her.

The activities were completed during two consecutive lessons held one week apart, as the students were away on a school trip for three days in between. The general procedure followed in both activities was the task-feedback circle proposed by Scrinever (1994).

Students sat at their desks, as they usually do in the English lessons. Desks were arranged in six groups of four to five students.

Both lessons were recorded on video, using two video cameras in order to record the faces of the students and myself, who was standing opposite to them. The size and spatial arrangement of the classroom did not make it possible to record all students with the video cameras, which were in a fixed position.

In the first lesson, I introduced briefly the activities of the two consecutive lessons and explained the general procedure that would be applied in both. Prior to that, their general classroom teacher had explained to them the purpose of the research, as outlined in section 3.5.

Both lessons followed the same pre-task phase, composed of the following steps:

- I introduced the topic of the story and we held a short discussion in order to activate prior knowledge and introduce some new key vocabulary that students were likely to encounter for the first time. This key vocabulary is listed in Appendix A. It was previously identified with the help of their EFL teacher, based on the semi-scripted text contained in Appendix B and on the ELEANITZ storybook.

- I handed each student a copy of the questionnaire to be answered after the listening activity, and we read and discussed the questions contained in it (see Appendix D), to make sure students had a chance to ask any doubts on their meaning.

- I explained that they should listen to the story with those questions in mind, that they would have five to ten minutes to write their answers after listening to the story, and that they were asked to do this individually.

Both the vocabulary preview and the question preview were included among the prelistening activities, as they have been reported to improve listening and reading comprehension (Elkhafaifi, 2005; Zeleke, 2013).

After the pre-task phase, in the first lesson I told the autobiographical story. In the second lesson, each student was given one copy of the storybook, and listened to the CD recording of the ELEANITZ story, while reading it in silence individually.

After the storytelling, I followed the same procedure in both lessons: I read each question in the questionnaire aloud, leaving time for the participants to answer it. Those who needed it were given extra time to answer the questions.

The second lesson ended with a short post-test survey, to assess participants’ attitudes towards the two stories, which can be found in Appendix D.

During the pre-task discussions, the students understood readily what the local questions requested, and their doubts concerned mainly vocabulary that was new to them. On the contrary, I experienced great difficulty in explaining the meaning of global questions four and seven of the questionnaire about the autobiographical story. That is the reason why question four, which dealt with summarising the story, was reformulated in the questionnaire for the ELEANITZ story, in order to make it easier to understand for the participants.

The storytelling of the autobiographical story lasted 11 minutes, and the ELEANITZ story’s CD recording lasted 5 minutes and 40 seconds.

Finally, there were some differences in the setting between the two lessons, as there was considerable noise coming from the corridor while the CD recording of the ELEANITZ story was played during the second lesson. In addition, the volume and sound quality of the CD player in that lesson were noticeably poorer than my live voice telling the autobiographical story in the first lesson.

The story taken from the ELEANITZ course materials is titled “Where’s the magician?” (Elorza et al., 2005). In summary, the story tells the adventures of six friends when they go to see a show by the Tilly Troupe in the local theatre. These six children are the characters in the stories of the “Story Projects” material that students go through during the third and fourth grades of primary. The friends arrange to go to the show and, once inside, the master of ceremonies requests volunteers to perform in the show, because the Tilly Troupe has not arrived yet. Two of the friends do magic tricks, other two tell jokes dressed up as clowns, and the last two sing and dance. Their performances are a great success.

Although the stories in ELEANITZ are usually introduced to students through collective dramatisation, this particular story is typically presented reading the storybook in silence while listening to the text being read on a CD recording (Gipuzkoako Ikastolen Elkartea, 2009).

The autobiographical story was titled “Hiking in Japan.” Careful thought was given to aspects linked with authenticity of the text due to its relationship with student motivation (Guariento & Morley, 2001), as well as to the importance of truthfulness in autobiographical stories (Leggo, 2007). As a result, it was decided to tell a truthful story, although it was adapted to the participants and the context. I wanted to share a personal story as a language learner and my struggles along the way, of the sort that Kazuyoshi (2002) reports being successful at creating a collaborative learning environment. Unfortunately, the school policy stated that EFL teachers should pretend to be native English speakers. Thus, I chose a personal story about my holidays in Japan, knowing just a few words of Japanese, hoping that it would echo the first experiences of the participants with English.

In summary, the autobiographical story tells how my husband and I bought food and prepared our rucksacks to spend a week hiking in the Japanese Alps. It explains our experience sleeping in our tent and in a mountain hut, our difficulties understanding maps and signs, and our experience making two Japanese friends, even though we spoke no Japanese and they spoke no English.

Figure 1. Examples of the A3 visual aid used in the autobiographical story

The semi-scripted text can be found in Appendix B. The autobiographical story was shaped following criteria to make input comprehensible (see Appendix C). However, this semi-scripted text was not read aloud, nor memorised, as recommended by Buck (2001).

The entire text of the ELEANITZ story and the semi-scripted text of the autobiographical story were subjected to the analysis of readability shown in Table 2, using the readability test performed by Microsoft Word 2010.

The Flesch Reading Ease test rates text on a 100-point scale. The higher the score, the easier it is to understand the text. The formula for the Flesch Reading Ease score is:

- 206.835 – (1.015 x ASL) – (84.6 x ASW)

The Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level test rates text on a U.S. school grade level. The formula for the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level score is:

- (.39 x ASL) + (11.8 x ASW) – 15.59

Where, ASL is the Average Sentence Length (the number of words divided by the number of sentences), and ASW is the Average of Syllables per Word (the number of syllables divided by the number of words).

Most standard texts have a Flesch Reading Ease score of 60-70. According to Zamanian & Heydari (2012), Flesch Reading Ease scores of 70-80 are interpreted as being fairly easy and suitable for seventh graders (ages 12 to 13), while scores of 80-90 are interpreted as being easy and suitable for sixth graders (ages 11 to 12).

I am aware that readability is a wide field of research and that alternatives to traditional readability indices have been proposed (e.g. Crossley, Allen, & McNamara, 2011; Crossley, Greenfield, & McNamara, 2008; Kouame, 2010), but it is beyond the scope of this study to analyse these issues in depth.

The information on readability is brought here only to illustrate that, as a starting point, the text of the autobiographical story was more challenging than the text of the ELEANITZ story.

For methodological triangulation purposes, three data collection instruments were used in order to answer the three research questions outlined in section 1.2. The first instrument for collecting data in the case study was the questionnaire, which contained eight questions. Questions one to seven formed the comprehension questionnaire, which is the data collection tool linked with the first research question. One comprehension questionnaire was designed and passed for each story in order to test general language proficiency related to the level of comprehension.

The other two data collection tools relate to the second research question. Student engagement was assessed using a behavioural observation instrument, which was filled while watching the video recordings of the two lessons. It is worth noticing that technical and spatial limitations in the EFL classroom had prevented from recording all the students who were present in both lessons.

A short post-survey test, run after the questionnaire of the ELEANITZ story, was used to study the perception and attitudes of the participants regarding both stories. This information was supplemented with the eighth question included in the questionnaires, which allowed assessing aspects linked to motivation.

Finally, regarding the third research question, three open-ended questions (questions 7 and 8 in the questionnaires, and question B in the post-test survey) allowed to test whether the participants used English or not in their responses.

The following subsections explain each instrument in detail.

As it has been mentioned, the first seven questions of the questionnaire (see Appendix D) formed the comprehension questionnaire. The questionnaire had an eighth question, which gave a chance to make connections between the story and the listener’s personal experience. The purpose of this last question was to assess aspects related to motivation, as it has been reported that content which is interesting and relevant for students plays an important role as an intrinsic factor, which improves levels of motivation (Nicholson, 2013). A story that one can relate to is expected to be interesting and relevant in this sense. This question complemented other motivational aspects analysed through the behavioural observation instrument explained in subsection 3.4.2.

Focusing on the comprehension questionnaire, there is a wide range of variables that affect comprehension. Besides the factors that influence comprehension and take place at the time of telling a story that have been analysed in section 2.6, there are also important aspects linked with the design of a questionnaire that can have an effect on comprehension (Buck, 2001; Ellis & Brewster, 2002; Guariento & Morley, 2001; Révész & Brunfaut, 2013; Rubin, 1994; Vandergrift, 2007). Appendix C explains the criteria that have guided the design of the comprehension questionnaires in this case study.

The main purpose of the comprehension questionnaires was to test general language proficiency. The first three questions were local questions that referred to exact details of the story, and the following four questions were global questions, which required synthesising information and making inferences. One of the global questions was related to understanding gist, one required integrating information from different passages of the story, another one asked the listener to draw a practical conclusion out of the story, and the seventh question required making an inference on the meaning of the story. Local and global questions were included for the purpose of assessing listening comprehension in a global way, as proposed by Buck (2001).

Questions 1 to 6 were traditional multiple-choice questions with four options, while questions 7 and 8 were open-ended questions. Traditional multiple-choice questions were chosen despite the fact that designing them is difficult (Buck, 2001), because this response format has been reported to help listeners understand oral texts and perform better in the test, especially when target language proficiency is low (Hsiao-fang, 2004).

Each of the multiple-choice questions had one or two distractors among the four possible answers that referred to events or details mentioned in the story, although they did not answer the question accurately. In the autobiographical story those details were sometimes introduced in the images used as visual aid, rather than in the text itself. In addition to the correct answer, one or two distractors among the options referred to aspects that were not part of the story. For instance, in the third question of the questionnaire on the autobiographical story, the correct answer was 2000 m, but the story mentioned that the mountain range itself has an altitude of 3000 m. The other two possible answers, 1000 m and 4000 m, were not mentioned in the story at all. The distractors that referred to aspects mentioned elsewhere in the story were introduced in order to detect partial or incomplete understanding of the story.

It must be remembered that the purpose of the case study regarding the first research question was to analyse comprehension, and not articulation ability in the target language. Thus, students were allowed to answer the open-ended questions in L1, in the same fashion as other studies have done (Elkhafaifi, 2005; Hsiao-fang, 2004; G.-P. Park, 2004; Révész & Brunfaut, 2013; Woodall, 2010). Additional evidence supporting this decision can be found in studies that have not allowed the use of L1 in open-ended questions and suggest that articulation ability may have caused test bias (McKendry & Murphy, 2011). Besides, allowing the students to use their L1 in the open-ended questions gave the opportunity to test the use of English in those questions, the object of the third research question.

Finally, the comprehension questionnaires were closely aligned with the official Basque curriculum contents for the second cycle of primary, which encompasses the third and fourth grades of primary, regarding EFL, as well as Basque and Spanish language (Gobierno Vasco. Departamento de Educación, Universidad e Investigación, 2010).

Connected with the second research question, a behavioural observation instrument was created, in order to assess student engagement during the two lessons that had been recorded. The increasing widespread of the use of computers in classrooms has recently allowed for detailed quantitative measuring of student behaviour (e.g. Bulger, Mayer, Almeroth, & Blau, 2008). Unfortunately, this was not our case, and the analysis of student engagement took into account observable behavioural measures, such as on-task and off-task behaviour frequency, adapting the behavioural observation checklists created by Ciampa (2012), Morgan (2008) and Turner et al. (2014).

On-task and off-task behaviours were recorded manually on the behavioural observation instrument using momentary time-sampling (sweeps) at seven-minute intervals during the video recording of each session. Every seven minutes along the recording, each student was briefly observed and his or her on-task or off-task behaviour was recorded on the behavioural observation instrument.

This technique was chosen for the sake of time and effort, bearing in mind that the results of the behavioural observation instrument were going to be partial, as only some students were recorded, and therefore the information drawn from it would be complementary to the data collected with the other tools. On the other hand, the fact that I told the autobiographical story myself prevented the use of other techniques based on field notes.

The post-test survey (see Appendix D) was also connected to the second research question and consisted of two questions, one multiple-choice and one open-ended. It intended to measure the perception and attitudes of the participants regarding both stories. It was kept very simple, bearing in mind that the participants would answer it after the questionnaire on the ELEANITZ story. Like in the open-ended questions in the questionnaires, participants were allowed to answer the open-ended question in L1, hence allowing for the collection of data related to the third research question.

As it has been pointed out in subsection 3.4.1, the post-survey test was complemented with the eighth question in the questionnaires. Following the criteria applied in similar studies (Taguchi, 2006), measures of motivation and attitude based on self-reporting were avoided. Therefore, participants were asked if the story reminded them of anything that had happened to them (question 8 of the questionnaire), which story they liked best (question A of the post-test survey), as well as which story they would choose if their general classroom teacher asked them to summarise one of the stories, and why (question B of the post-test survey).

Although no specific guidelines regarding ethical issues for research by undergraduate students were communicated by the university, I have considered ethical aspects in my research design.

This study does not involve discussion of sensitive topics. No harmful or negative consequences could be expected for the participants or me during the activities involved.

In order to ensure that the students understood the activities proposed to them and the context of the study, I asked their general classroom teacher to explain them in Basque, based on some notes I prepared beforehand.

In summary, students were aware that they were free to decide whether to take part in the activities or not (listening to the ELEANITZ story was compulsory, though), that the results would not be taken into account in the assessment of the English unit, and that I would give them feedback on the findings of the study.

This chapter analyses the data collected in the study in order to draw the key results. The chapter is divided in sections, named after the instruments for data collection, which summarise the findings derived from the data collection tools, and highlight the key results obtained.

Questions 1 to 7 of the questionnaires formed the comprehension questionnaires, which relate to the first research question, and are analysed in this section. The results of the eighth question are discussed in sections 4.3 and 4.4, as that question deals primarily with motivational and attitudinal aspects related to the second research question.

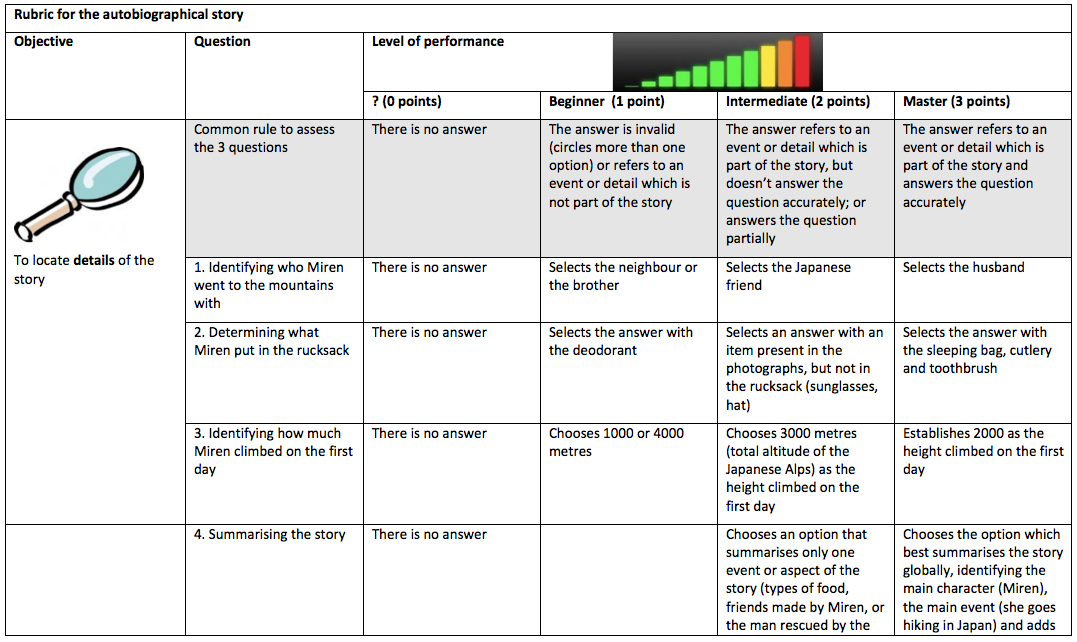

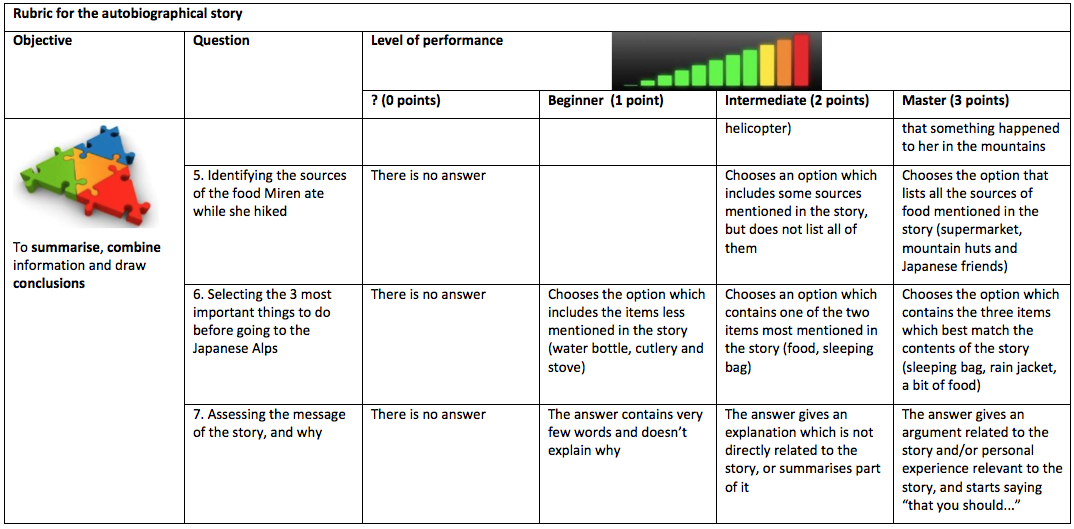

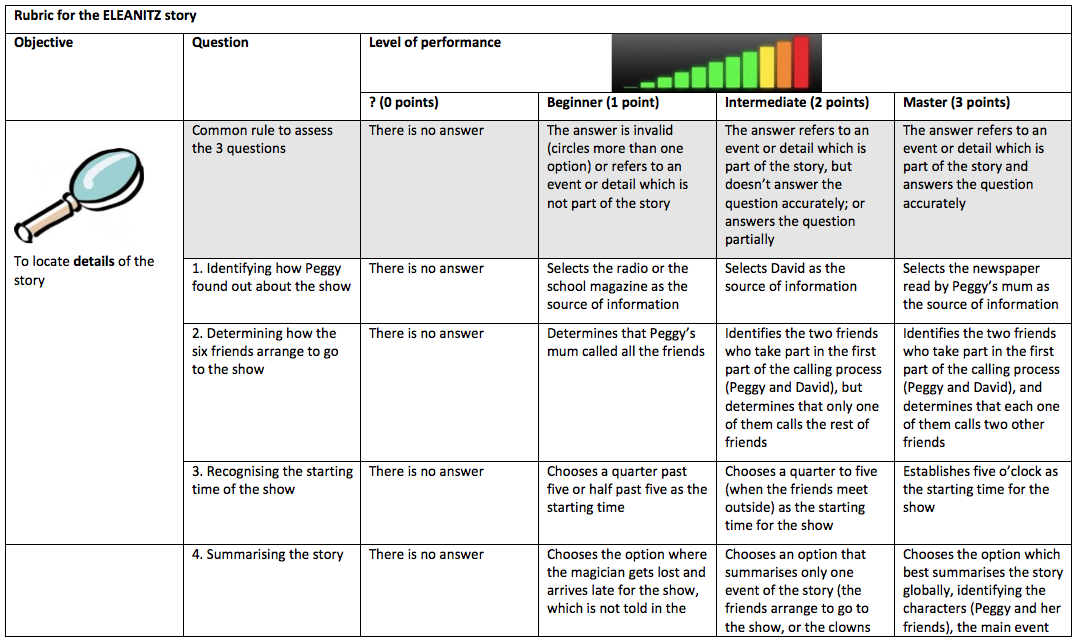

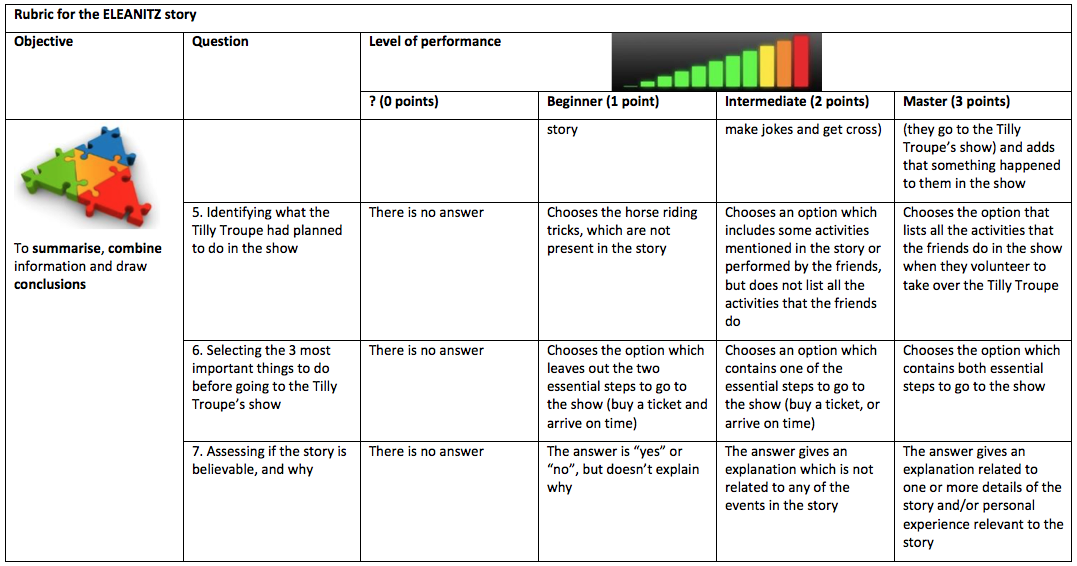

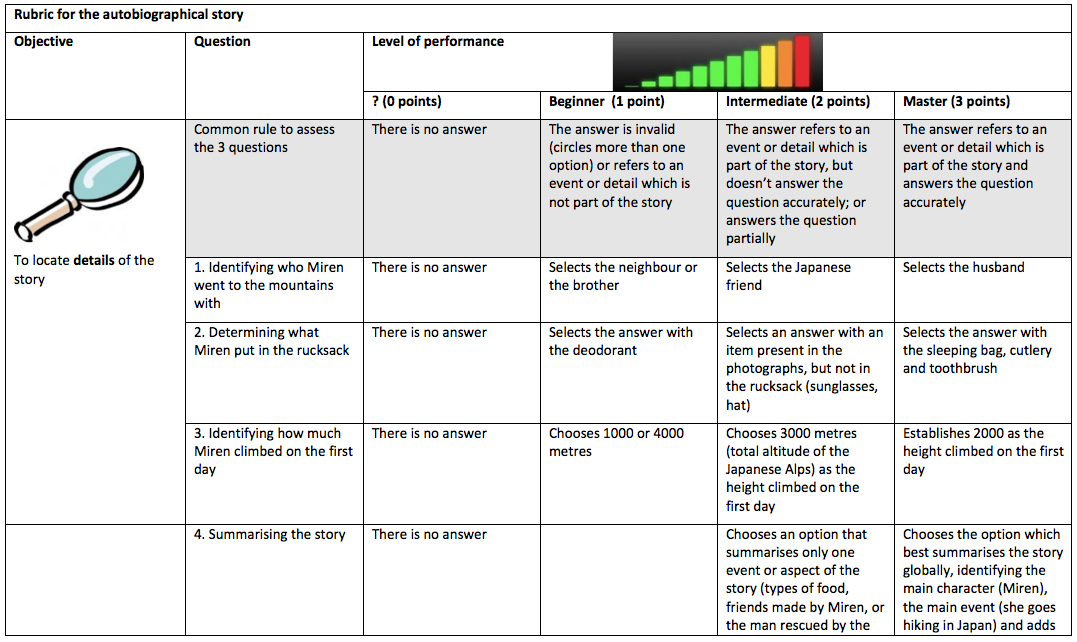

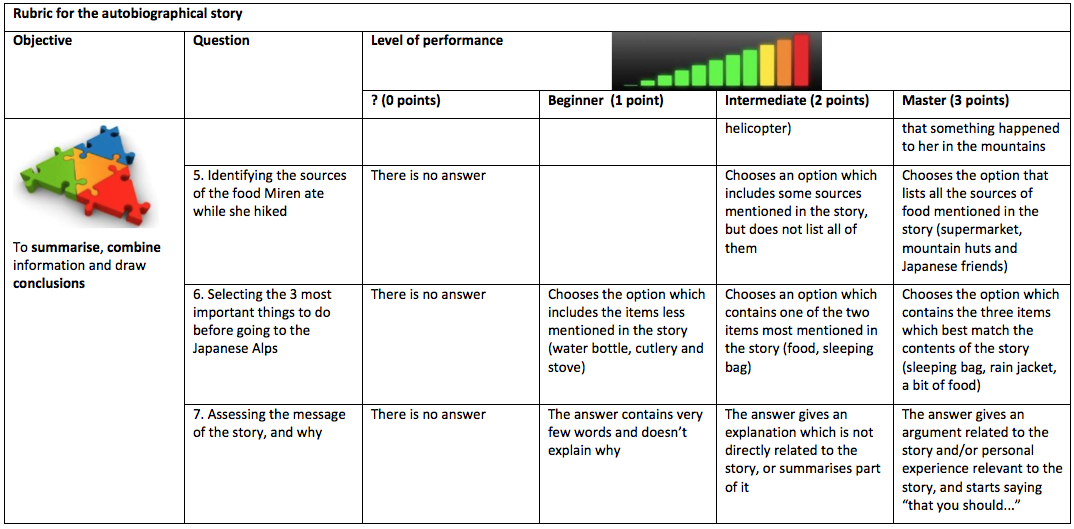

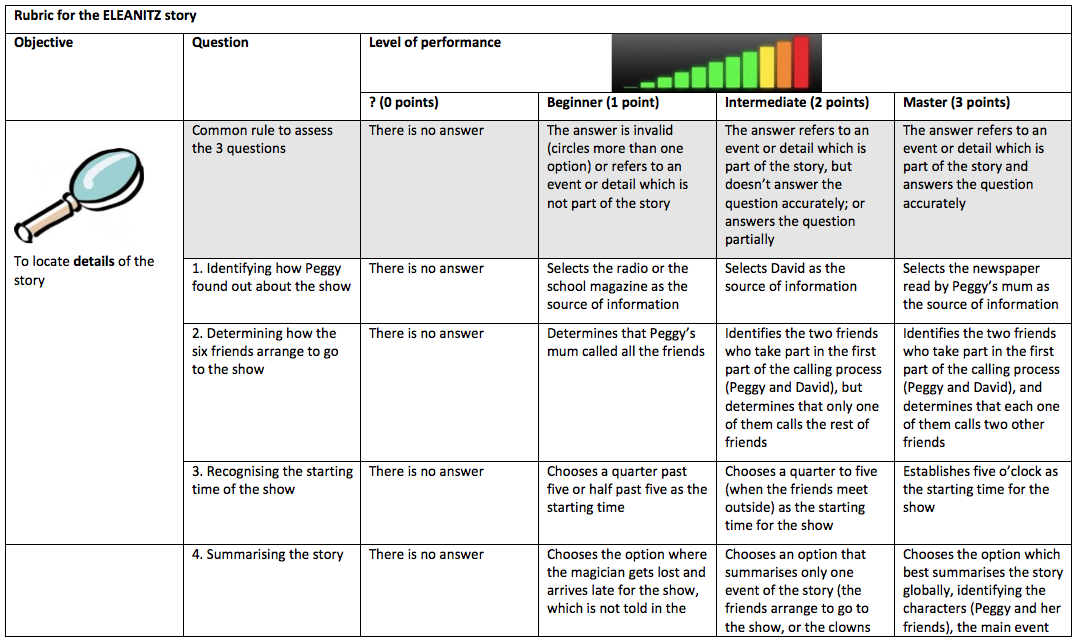

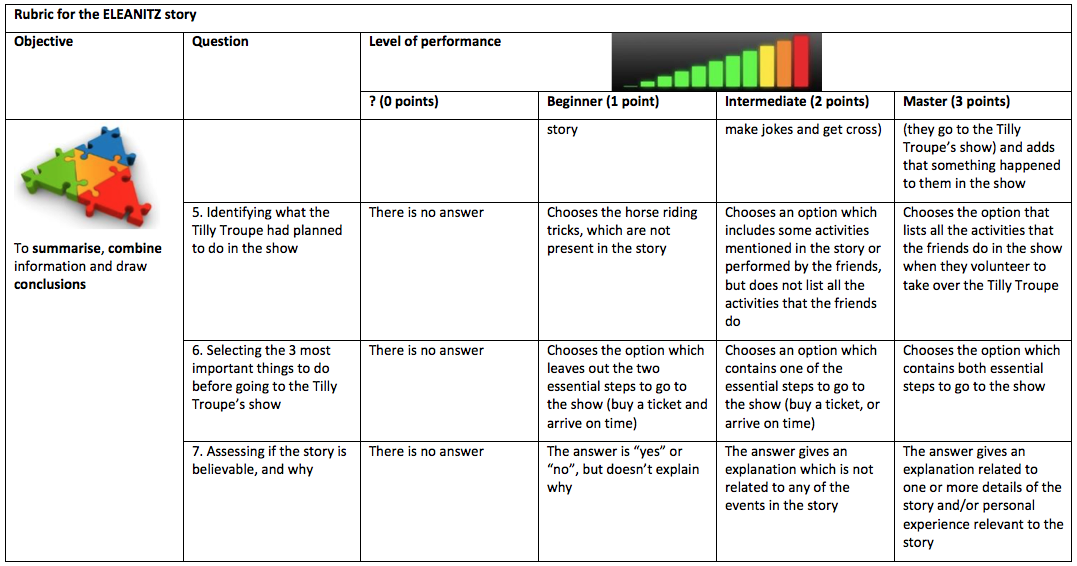

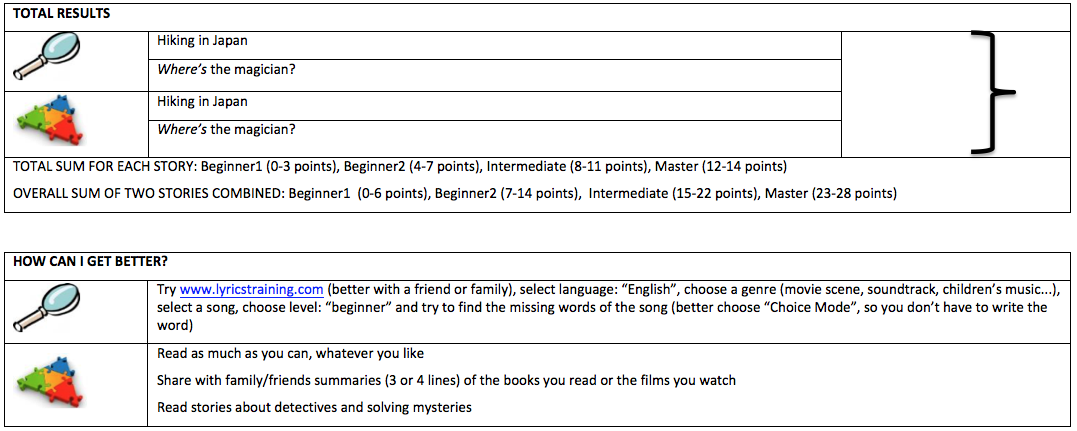

The answers to the comprehension questionnaires were evaluated using a scoring rubric. The rubric was designed following widely accepted criteria and guidelines and was based on several models (Allen & Tanner, 2006; Andrade, 2005; Arter, 2000; Birky, 2012; Boston, 2002; Cheyney, 2010; De La Paz, 2009; Hegler, 2003; Livingston, 2012; Mertler, 2001; Moskal, 2000b, 2003; Whittaker, Salend, & Duhaney, 2001; Yoshina & Harada, 2007). Appendix E contains more details on the process of creation of the rubric, and the rubric itself.

The number of participants in the first lesson, which dealt with the autobiographical story, was different from the number of participants in the second lesson, where the ELEANITZ story was used, as shown in Table 3. This had effects over the total maximum possible score for each participant, as will be discussed along this section.

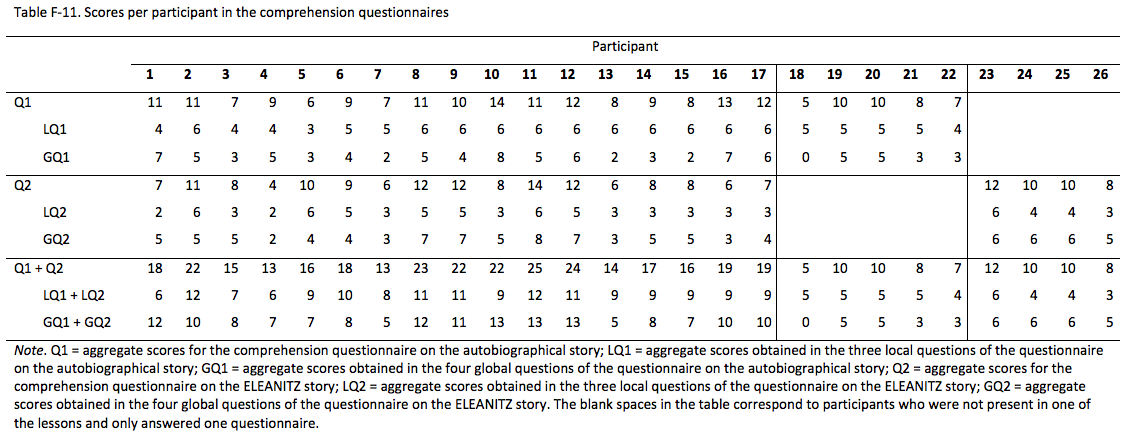

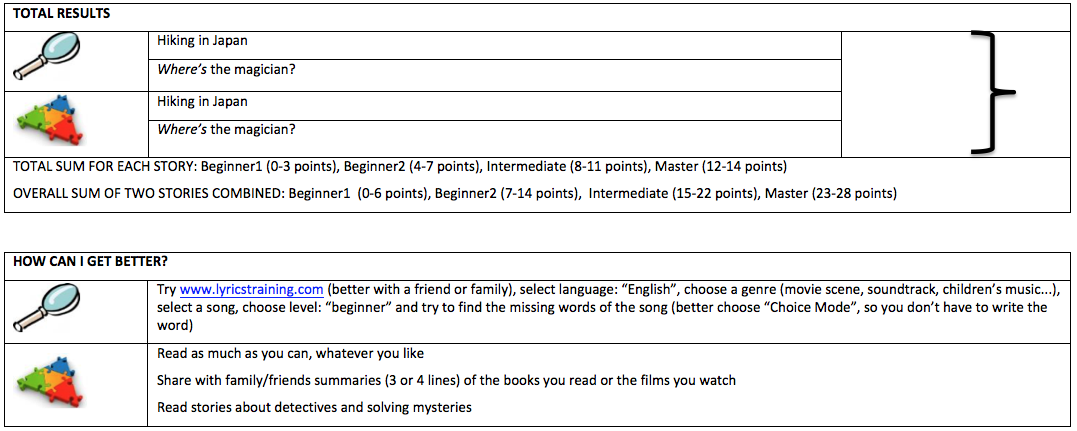

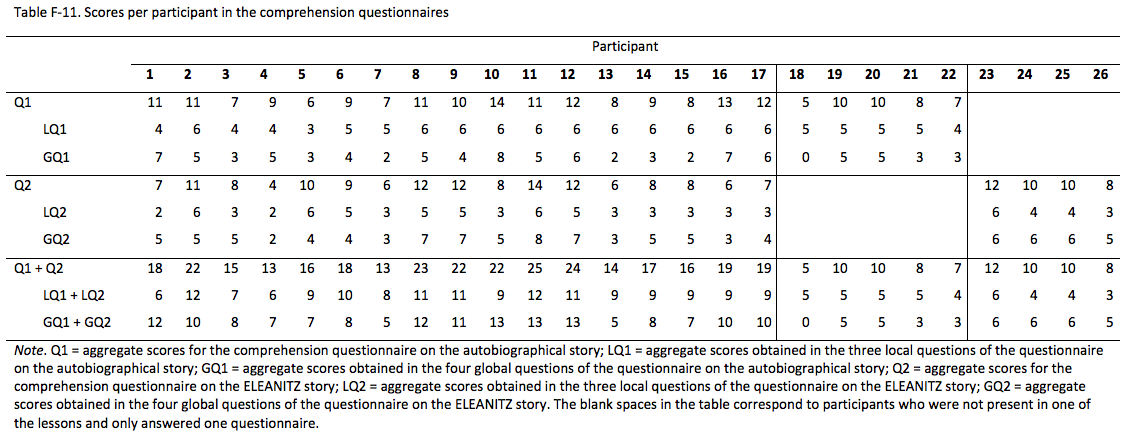

Table F-11 in Appendix F shows the scores that each participant obtained in the comprehension questionnaires of both stories.

Scores were awarded as follows: 2 points for a full response; 1 point for a partial response (the answer referred to an event or detail which was part of the story, but did not answer the question accurately or answered it partially); and 0 points for incorrect responses (the answer referred to an event or detail not mentioned in the story) or lack of response.

The quantitative data derived from the comprehension questionnaires was analysed using simple descriptive statistics, such as frequencies, means, medians, standard deviations and percentages.

Table 4 summarises the overall achievement of the participants in the comprehension questionnaires (N = 26). For instance, the first value shows that two participants (7.7% over the 26) gave full responses in 80 to 100% of the questions in both questionnaires.

Therefore, 46.2% of the participants gave full responses in 40 to 60% of the questions of both questionnaires, 57.7% gave partial responses in 20 to 40% of the questions, and 57.7% of the participants did not respond or gave an incorrect answer in less than 20% of the questions.

Discarding the scores of the nine participants who, having taken part only in one lesson, had answered just one questionnaire would have simplified considerably the data analysis. Yet, that would have meant leaving aside the scores of 35% of the participants. Therefore, it was decided to analyse all data, and calculate weighted values where applicable.

The maximum possible score for participants who answered both questionnaires, as well as for those who only took one, are summarised in Table 5.

The scores for each of the two comprehension questionnaires are best viewed in the form of percentages over the maximum possible score. Table 6 shows that overall participants obtained higher comprehension scores for the autobiographical story than for the ELEANITZ story, with a difference of 3.59 points on the mean (%) and 8.32 on the median (%).

On the other hand, local questions scored higher than global questions, with a difference of 19.63 points on the mean (%) and 15.71 points on the median (%). However, there were noticeable differences between both stories: in the autobiographical story, local questions scored much higher than global questions, having a difference of 34.28 points on the mean (%) and 35.42 points on the median (%). In the ELEANITZ story, local questions and global questions showed a very different pattern, with a difference of 3.37 points in favour of local questions on the mean (%) and 12.50 points in favour of global questions on the median (%).

These contradictory results are in line with previous studies, which have proven the complex nature of the interaction of question types with background and linguistic knowledge (G.-P. Park, 2004),

Finally, a paired samples t-test was conducted for the participants who took both comprehension questionnaires (n = 17), based on the scores for the autobiographical story (M = 9.88, SD = 2.26) and the ELEANITZ story (M = 8.71, SD = 2.73), t(16) = 1.51, two-tail p = .15. The results showed no statistically significant differences between the scores of the participants in the two comprehension questionnaires.

Since p value depends on sample size, the sample size independent effect size was also calculated for the scores of the 17 participants who answered both comprehension questionnaires; Cohen’s d = 0.48, and dunbiased = 0.46. The latter (sometimes called Hedge’s g) was calculated because it is more suitable than Cohen’s d when sample size is small (Fritz, Morris, & Richler, 2012). Hattie (2009) has established that in educational contexts Cohen’s d > 0.40 should be interpreted as the method or intervention researched having desired effects.

The behavioural observation instrument was related to the second research question, which dealt with differences in motivation and engagement. The results of this instrument were supplemented with the questions analysed in section 4.3.

The video recordings of the two lessons had different lengths because the lesson around the ELEANITZ story took longer than the lesson on the autobiographical story. Therefore, students were observed seven times during the lesson on the autobiographical story, and eight times during the lesson on the ELEANITZ story. The last observation of each lesson was discarded because it fell within an interval of the video recording where the activity itself had already finished, and students were handing in their questionnaires and tidying up their desks.

It was difficult to observe on-task and off-task behaviour during the storytelling of the ELEANITZ story, since the participants were looking down on their storybooks, but it was not possible to observe if they were actually reading and following the story. A conservative approach was adopted, and behaviour was considered off-task only when it was obvious.

On the other hand, even though the number of participants observed in both lesson is the same, they correspond to different individuals, as 10 participants were observed in the two lessons, 4 only in the first lesson, and 4 only in the second lesson.

All off-task behaviour observed was categorised as stalling (looking out the window, flicking through papers, playing with the pencil case). Only one participant showed off-task behaviour in the sixth sweep during the lesson on the autobiographical story, while the participants answered the questionnaire as I read one of the questions aloud. This was actually the student who showed signs of deep disengagement at school in all subjects, and who only took part in the first lesson.

During the lesson on the ELEANITZ story, four participants showed off-task behaviour in the third sweep, while participants predicted the contents of the story based on the cover of the storybook during the pre-task phase of the activity, and one participant did the same in the third and sixth sweeps. The sixth sweep of the second lesson corresponds to the moment when the participants were listening to the ELEANITZ story being told on the CD recording.

Among the participants who showed off-task behaviour, three took part only in one lesson – including the participant with off-task behaviour in the first lesson – and three took part in both lessons.

The eighth question in the questionnaires, together with the two questions of the post-test survey, served to analyse engagement, motivation and attitude towards the two stories, which relate to the second research question. Therefore, this information complements the observation of student behaviour explained in section 4.2.

Table 8 shows that when asked if the autobiographical story reminded them of anything that had happened to them in the past (question eight of the questionnaires), 41% of the participants did so affirmatively. On the contrary, the ELEANITZ story triggered no recalls of autobiographical stories in the participants.

The contents of the autobiographical stories written by the participants in response to the eighth question of the questionnaire reveal the elements of the autobiographical story that they related to mostly. Five participants mentioned particular mountains nearby (Santiagomendi, Adarra, Onddi), and two mentioned hiking.

Most significantly, four participants narrated stories of incidents (three in the mountains, one elsewhere), which echoed the part of the autobiographical story on the man who had to be rescued by a helicopter. It is worth mentioning that 16 of the 22 participants had summarised the autobiographical story in question 4 of the comprehension questionnaire selecting the option that stated that the story was about a man who had a heart attack and had to be rescued in a helicopter.

Given the little time that the participants had to answer the questionnaire, their stories ranged from little more details than the name of the mountain where their personal story took place, to elaborate narratives such as “One day I went hiking with my cousins and uncles. While we were in the mountains, we saw a chapel and went inside, and we were locked. My cousin made a call on the mobile phone and in the end; a man came to rescue us.”

As regards the post-test survey, Table 9 shows that the autobiographical story was liked best, and the participants would prefer it to the ELEANITZ story if they had to choose one to summarise. In particular, 71% of the participants liked the autobiographical story more, and 47% would prefer to summarise it.

Seven participants explained why they liked the autobiographical story more than the ELEANITZ story. Two of them showed emotional connections with mountain landscapes. The remaining five claimed that the autobiographical story was more interesting, more fun and/or nicer.

In contrast, among the three participants who liked the ELEANITZ story better, two justified their choice because it was easier, while the third added to that the fact that there was dance and magic in the story. Interestingly, one of these students obtained the highest score in the sum of both comprehension questionnaires shown in Figure 2, another student was also in the top third of that list, and the third student right in the middle.

Figure 2. Score for each participant in the comprehension questionnaires

Note. 2 points = full response; 1 point = partial response, as the answer referred to an event or detail which was part of the story, but did not answer the question accurately or answered it partially; 0 points = lack of response or incorrect response, as the answer referred to an event or detail not mentioned in the story. Scores are displayed as percentage over the maximum score possible.

Finally, considering that only 6 out of the 17 participants who answered the two questionnaires answered the eighth question in both, the statistical significance of the results was not tested. The same decision was taken for the post-survey questions.

Questions 7 and 8 in the questionnaires and question B in the post-test survey were open-ended questions, allowing for the collection of data related to the third research question on the use of English in the responses. The participants were given the choice to answer those questions in L1, and they were not encouraged in any way to use English. Therefore, it was a surprise to find that some participants used English when they answered those questions, as Table 10 shows.

However, the participants only included explanations in English in the questionnaire on the autobiographical story. Among the three participants who used some English in their explanations in that questionnaire, two only took part in that lesson. The only participant who used some English in the post-test survey attended just the second lesson.

It is interesting to notice that two of the participants who used some English in the questionnaire actually obtained the two lowest scores in the sum of both comprehension questionnaires shown in Figure 2. The third participant was also among the bottom third of the list, while the participant who used some English in the post-test survey obtained the second best score.

Thus, mainly low achievers in the comprehension questionnaires used English in their explanations of the open-ended questions. These results are consistent with previous studies that explored the relationship between listening test scores and motivation orientations, finding that “a high degree of motivation does not appear to be a reliable predictor of proficiency in L2 listening comprehension” (Vandergrift, 2005, p. 79).Continued on Next Page »

Ajayi, L. (2011). Video ‘Reading’ and Multimodality: A Study of ESL/Literacy Pupils’ Interpretation of Cinderella from Their Socio-Historical Perspective. The Urban Review, 44(1), 60–89. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11256-011-0175-0

Allen, D., & Tanner, K. (2006). Rubrics: Tools for Making Learning Goals and Evaluation Criteria Explicit for Both Teachers and Learners. CBE - Life Sciences Education, 5(3), 197–203.

Alley, D., & Overfield, D. (2008). An Analysis of the Teaching Proficiency Through Reading and Storytelling (TPRS) Method. In C. Wilkerson & C. M. Cherry (Eds.), Languages for the Nation. Dimension 2008. Selected Proceedings of the 2008 Joint Conference of the Southern Conference on Language Teaching and the South Carolina Foreign Language Teachers’ Association (pp. 13–25). Southern Conference on Language Teaching. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED503097

Andrade, H. G. (2005). Teaching with Rubrics: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. College Teaching, 53(1), 27–30.

Arter, J. (2000). Rubrics, Scoring Guides, and Performance Criteria: Classroom Tools for Assessing and Improving Student Learning. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New Orleans, LA. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED446100

Artigal, J. M. (1990). Uso-Adquisición de una Lengua Extranjera en el Marco Escolar Entre los Tres y los Seis Años. CL & E: Comunicación, Lenguaje y Educación, (7), 127–144.

Arzamendi, J., Etxeberria, J., Garagorri, X., Elorza, I., Ball, P., & Lindsay, D. (2003). A los 10 Años de Evaluación de la Experiencia Eleanitz-Inglés. Enseñanza-Aprendizaje de las Lenguas Extranjeras en Edades Tempranas, 143–174.

Azpillaga, B., Arzamendi, J., Etxeberria, F., Garagorri, X., Lindsay, D., & Joaristi, L. (2001). Preliminary Findings of a Format-Based Foreign Language Teaching Method for School Children in the Basque Country. Applied Psycholinguistics, 22(1), 35–44.

Birky, B. (2012). Rubrics: A Good Solution for Assessment. Strategies, 25(7), 19–21.

Boston, C. (2002). Understanding Scoring Rubrics: A Guide for Teachers. College Park, MD: ERIC Clearinghouse on Assessment and Evaluation. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED471518

Bromer, J. (1995). When I Was a Baby: Autobiographical Talk in a Preschool Classroom. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/eric/docview/62552414/abstract/E7835A1856E34006PQ/1?accountid=17248

Bryant, S. C. (2008). How to Tell Stories to Children and Some Stories to Tell. Tennessee: Dodo Press.

Buck, G. (2001). Assessing Listening. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press.

Bulger, M. E., Mayer, R. E., Almeroth, K. C., & Blau, S. D. (2008). Measuring Learner Engagement in Computer-Equipped College Classrooms. Journal of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia, 17(2), 129–143.

Cain, K., Oakhill, J. V., Barnes, M. A., & Bryant, P. E. (2001). Comprehension Skill, Inference-Making Ability, and Their Relation to Knowledge. Memory & Cognition, 29(6), 850–859.

Cenoz, J. (2011). The Increasing Role of English in Basque Education. English in Europe Today. Sociocultural and Educational Perspectives, 15–30.

Cenoz, J., & Etxague, X. (2011). Third Language Learning and Trilingual Education in the Basque Country. In S. Björklund & I. Bangma, Trilingual Primary Education in Europe: Some Developments With Regard to the Provisions of Trilingual Primary Education in Minority Language Communities of the European Union (pp. 32–44). Ljouwert/Leeuwarden: Fryske Akademy; Mercator Education.

Cheng, H.-F., & Dörnyei, Z. (2007). The Use of Motivational Strategies in Language Instruction: The Case of EFL Teaching in Taiwan. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 1(1), 153–174. http://doi.org/10.2167/illt048.0

Cheyney, D. A. (2010). The Use of Rubrics for Assessment of Student Learning in Higher Education (Doctoral Dissertation). Talbot School of Theology, Biola University, La Mirada, CA. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/eric/docview/860152539/abstract/E2CE33D7361F4D35PQ/10?accountid=17248

Ciampa, K. (2012). ICANREAD: The Effects of an Online Reading Program on Grade 1 Students’ Engagement and Comprehension Strategy Use. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 45(1), 27–59.

Crossley, S. A., Allen, D. B., & McNamara, D. S. (2011). Text Readability and Intuitive Simplification: A Comparison of Readability Formulas. Reading in a Foreign Language, 23(1), 84–101.

Crossley, S. A., Greenfield, J., & McNamara, D. S. (2008). Assessing Text Readability Using Cognitively Based Indices. TESOL Quarterly: A Journal for Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages and of Standard English as a Second Dialect, 42(3), 475–493.

Daniel, A. K. (2012). Storytelling across the primary curriculum. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon; New York: Routledge.

Davis, E. A., Beyer, C., Forbes, C. T., & Stevens, S. (2011). Understanding Pedagogical Design Capacity Through Teachers’ Narratives. Teaching and Teacher Education: An International Journal of Research and Studies, 27(4), 797–810.

De La Paz, S. (2009). Rubrics: Heuristics for Developing Writing Strategies. Assessment for Effective Intervention, 34(3), 134–146. http://doi.org/10.1177/1534508408318802

Desjardins, E. N. (2011). Small Stories for Learning: A Sociocultural Analysis of Children’s Participation in Informal Science Education (Doctoral Dissertation). Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, NY. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/eric/docview/1023531028/abstract/D5393755946543FEPQ/1?accountid=17248

Dewitz, P., Leahy, S. B., Jones, J., & Sullivan, P. M. (2010). The Essential Guide to Selecting and Using Core Reading Programs. Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Dörnyei, Z. (1994). Motivation and Motivating in the Foreign Language Classroom. Modern Language Journal, 78(3), 273–284.

Dörnyei, Z. (2001). New Themes and Approaches in Second Language Motivation Research. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 21(1), 43–59.

Dörnyei, Z., & Csizér, K. (1998). Ten Commandments for Motivating Language Learners: Results of an Empirical Study. Language Teaching Research, 2(3), 203–229. http://doi.org/10.1177/136216889800200303

Elkhafaifi, H. (2005). The Effect of Prelistening Activities on Listening Comprehension in Arabic Learners. Foreign Language Annals, 38(4), 505–513. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.2005.tb02517.x

Ellis, G., & Brewster, J. (Eds.). (1991). The Storytelling Handbook for Primary Teachers. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books Ltd.

Ellis, G., & Brewster, J. (2002). Tell it Again! The New Storytelling Handbook for Primary Teachers. Harlow: Penguin English.

Elorza, I. (2005). Ikastolen ‘Eleanitz’ Proiektua: Euskara Ardaztzat Duen Eleaniztasuna. Jakingarriak, (57), 22–27.

Elorza, I., Fano, D., & Tejada, E. (2005). Where’s the Magician?. Donostia: Ikastolen Elkartea.

Elorza, I., & Muñoa, I. (2008). Promoting the Minority Language Through Integrated Plurilingual Language Planning: The Case of the Ikastolas. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 21(1), 85–101. http://doi.org/10.2167/lcc345.0

Euskal Herriko Ikastola EKE (EHI EKE). (2013). Eleanitz Project. Retrieved 4 January 2015, from http://www.eleanitz.org/public/Eleanitz_Project

Fox, M. (2008). Reading Magic: Why Reading Aloud to Our Children Will Change Their Lives Forever (Updated end rev ed.). Orlando, Fla: Harcourt.

Fox, M. (2013). What Next in the Read-Aloud Battle? Win or Lose? The Reading Teacher, 67(1), 4–8. http://doi.org/10.1002/TRTR.1185

Freadman, A. (2014). Fragmented Memory in a Global Age: The Place of Storytelling in Modern Language Curricula. The Modern Language Journal, 98(1), 373–385. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2014.12067.x

Fritz, C. O., Morris, P. E., & Richler, J. J. (2012). Effect Size Estimates: Current Use, Calculations, and Interpretation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 141(1), 2–18. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0024338

Garagorri, X., Elorza, I., & Lindsay, D. (1997). ELEANITZ Eleaniztasuneko Proiektua, Ingelesa 4 Urtetik Aurrera Irakastea. Jakingarriak, 36, 30–39.

Garvie, E. (1990). Story as Vehicle: Teaching English to Young Children. Clevedon; Philadelphia: Multilingual Matters, Ltd.

Gipuzkoako Ikastolen Elkartea. (2009). Story Projects Tutorial. Story Projects 2. Teacher’s Guide.

Gobierno Vasco. Departamento de Educación, Universidad e Investigación. (2010). Decretos curriculares para la Educación Infantil, Básica y Bachiller en la Comunidad Autónoma del País Vasco. Retrieved from http://www.hezkuntza.ejgv.euskadi.net/r43-2459/es/contenidos/informacion/dig_publicaciones_innovacion/es_curricul/adjuntos/14b_curriculum/320002c_Pub_EJ_curriculum_basica_c.pdf

González Somocurcio, J. (2014). Eleanitz Proiektuak Dituen Hutsuneak. Irakaslearen ikuspegia (Undergraduate Dissertation). Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea - Universidad del País Vasco, Bilbao. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10810/14017

Guariento, W., & Morley, J. (2001). Text and Task Authenticity in the EFL Classroom. ELT Journal, 55(4), 347–353. http://doi.org/10.1093/elt/55.4.347

Guilloteaux, M.-J. (2013). Motivational Strategies for the Language Classroom: Perceptions of Korean Secondary School English Teachers. System: An International Journal of Educational Technology and Applied Linguistics, 41(1), 3–14.

Guilloteaux, M. J., & Dörnyei, Z. (2008). Motivating Language Learners: A Classroom-Oriented Investigation of the Effects of Motivational Strategies on Student Motivation. TESOL Quarterly: A Journal for Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages and of Standard English as a Second Dialect, 42(1), 55–77.

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible Learning: A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement. London; New York: Routledge.

Hegler, K. L. (2003). Using General Education Assessment Rubrics to Document Basic Skills and Content Knowledge. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New Orleans, LA. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED472812

Howe, A., & Johnson, J. (1992). Common Bonds: Storytelling in the Classroom. London: Hodder & Stoughton.

Hsiao-fang, C. (2004). A Comparison of Multiple-Choice and Open-Ended Response Formats for the Assessment of Listening Proficiency in English. Foreign Language Annals, 37(4), 544–555.

Ikastolen Elkarteko Eleanitz-Ingelesa Taldea. (2003). Eleanitz-English: Gizarte Zientziak Ingelesez. Bat: Soziolinguistika Aldizkaria, (49), 79–98.

Kazuyoshi, S. (2002). Contagious Storytelling. The Language Teacher, 26(Special Issue: The Narrative Mind), 15–25.

Keane, J. T. (2010). Student Multimedia Autobiographies: The Roles of Technology, Personal Narrative, and Signifying Practices (Doctoral Dissertation). University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/eric/docview/898324097/abstract/D07BEE47EFD84FB3PQ/1?accountid=17248

Kobayashi, M. (2012). A Digital Storytelling Project in a Multicultural Education Class for pre-Service Teachers. Journal of Education for Teaching, 38(2), 215–219. http://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2012.656470

Kohn, A. (2006). The Trouble With Rubrics. English Journal,High School Edition, 95(4), 12–15.

Kouame, J. B. (2010). Using Readability Tests to Improve the Accuracy of Evaluation Documents Intended for Low-Literate Participants. Journal of MultiDisciplinary Evaluation, 6(14), 132–139.

Kugelmass, J. W. (2000). Subjective Experience and the Preparation of Activist Teachers: Confronting the Mean Old Snapping Turtle and the Great Big Bear. Teaching and Teacher Education, 16(2), 179–194.

Lasagabaster Herrarte, D. (2011). Basque as a Minority Language and English as a Foreign Language: Are They Complementary Languages in the Basque Educational System? Annales-Anali Za Istrske in Mediteranske Studije, 21(1), 93–100.

Le Fevre, D. M. (2011). Creating and Facilitating a Teacher Education Curriculum Using Preservice Teachers’ Autobiographical Stories. Teaching and Teacher Education: An International Journal of Research and Studies, 27(4), 779–787.

Leggo, C. (2007). Writing Truth in Classrooms: Personal Revelation and Pedagogy. International Journal of Whole Schooling, 3(1), 27–37.

Liu, C.-C., Wu, L. y., Chen, Z.-M., Tsai, C.-C., & Lin, H.-M. (2014). The Effect of Story Grammars on Creative Self-Efficacy and Digital Storytelling. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 30(5), 450–464. http://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12059

Livingston, M. (2012). The Infamy of Grading Rubrics. English Journal,High School Edition, 102(2), 108–113.

Lund, R. J. (1991). A Comparison of Second Language Listening and Reading Comprehension. The Modern Language Journal, 75(2), 196–204. http://doi.org/10.2307/328827

McKendry, M. G., & Murphy, V. A. (2011). A Comparative Study of Listening Comprehension Measures in English as an Additional Language and Native English-Speaking Primary School Children. Evaluation & Research in Education, 24(1), 17–40. http://doi.org/10.1080/09500790.2010.531702

Meddings, L., & Thornbury, S. (2009). Teaching Unplugged. Dogme in English Language Teaching. Peaslake: Delta Publishing.

Menezes, H. (2012). Using Digital Storytelling to Improve Literacy Skills. In Proceedings of the International Association for Development of the Information Society (Iadis) International Conference on Cognition and Exploratory Learning in Digital Age (Celda) (Madrid, Spain, October19-21, 2012). Madrid, Spain: International Association for the Development of the Information Society. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED542821

Mertler, C. A. (2001). Designing Scoring Rubrics for Your Classroom. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 7(25).

Morgan, G. L. (2008). Improving Student Engagement: Use of the Interactive Whiteboard as an Instructional Tool to Improve Engagement and Behavior in the Junior High School Classroom (Doctoral Dissertation). Liberty University, Lynchburg, VA. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1140&context=doctoral&sei-redir=1&referer=http%3A%2F%2Fscholar.google.es%2Fscholar%3Fhl%3Den%26q%3Dstudent%2Bengagement%2Bchecklist%26btnG%3D%26as_sdt%3D1%252C5#search=%22student%20engagement%20checklist%22

Morgan, J. (1983). Once Upon a Time: Using Stories in the Language Classroom. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press.

Moskal, B. M. (2000a). Scoring Rubrics Part I: What and When. ERIC/AE Digest. ERIC Digests. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED446110

Moskal, B. M. (2000b). Scoring Rubrics: What, When and How? Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 7(3). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/eric/docview/62234228/E2CE33D7361F4D35PQ/34?accountid=17248

Moskal, B. M. (2003). Developing Classroom Performance Assessments and Scoring Rubrics - Part II. ERIC Digest. ERIC Digests. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED481715

Msila, V. (2011). Autobiographical Narrative in a Language Classroom: a Case Study in a South African School. Language and Education, 26(3), 233–244. http://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2011.636820

Nicholson, S. J. (2013). Influencing Motivation in the Foreign Language Classroom. Journal of International Education Research, 9(3), 277.

Panadero, E., & Jonsson, A. (2013). The Use of Scoring Rubrics for Formative Assessment Purposes Revisited: A Review. Educational Research Review, 9, 129–144. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2013.01.002

Paran, A., & Watts, E. (Eds.). (2003). Storytelling in ELT. Whitstable: IATEFL.

Park, G. (2011). Adult English Language Learners Constructing and Sharing Their Stories and Experiences: The Cultural and Linguistic Autobiography Writing Project. TESOL Journal, 2(2), 156–172.

Park, G.-P. (2004). Comparison of L2 Listening and Reading Comprehension by University Students Learning English in Korea. Foreign Language Annals, 37(3), 448–458.

Peacock, M. (1997). The Effect of Authentic Materials on the Motivation of EFL Learners. ELT Journal, 51(2), 144–156. http://doi.org/10.1093/elt/51.2.144

Peñate Cabrera, M., & Bazo Martínez, P. (2001). The Effects of Repetition, Comprehension Checks, and Gestures, on Primary School Children in an EFL Situation. ELT Journal, 55(3), 281–288. http://doi.org/10.1093/elt/55.3.281

Pennac, D. (2008). Como una Novela (12th ed.). Barcelona, Spain: Anagrama.

Petit, S., Mougenot, C., & Fleury, P. (2011). Stories on Research, Research on Stories. Journal of Rural Studies, 27(4), 394–402.

Pilon, E. M. (1993). Autobiography and Writing Across the Curriculum: Bringing ‘Life’ to Disciplinary Writing (p. 24). Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Conference on College Composition and Communication, San Diego, CA. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/eric/docview/62772270/abstract/27539FC981C048E9PQ/1?accountid=17248

Quackenbush, J. L. (2010). Writing (and Re-Writing) a Gendered Educational Life: Envisioning Possibilities for Teachers’ Autobiographical Texts (Doctoral Dissertation). Columbia University, New York, NY. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/eric/docview/881461769/abstract/2A8F1D52FB314668PQ/1?accountid=17248

Read, C. (2007). 500 Activities for the Primary Classroom. Immediate Ideas and Solutions. Oxford: Macmillan Education.

Reason, P., & Bradbury-Huang, H. (2001). Introduction: Inquiry and Participation in Search of a World Worthy of Human Inspiration. In P. Reason & H. Bradbury-Huang (Eds.), Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice (pp. 1–13). London; Thousand Oaks, Calif: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Révész, A., & Brunfaut, T. (2013). Text Characteristics of Task Input and Difficulty in Second Language Listening Comprehension. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 35(1), 31–65. http://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0272263112000678

Rivera Maulucci, M. S. (2011). Language Experience Narratives and the Role of Autobiographical Reasoning in Becoming an Urban Science Teacher. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 6(2), 413–434.

Rossiter, M. (2002). Narrative and Stories in Adult Teaching and Learning. ERIC Digest. ERIC Digests, 4.

Rossiter, M., & Clark, M. C. (2007). Narrative and the Practice of Adult Education. Malabar, FL: Krieger Publishing Company.

Rubin, J. (1994). A Review of Second Language Listening Comprehension Research. The Modern Language Journal, 78(2), 199–221. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1994.tb02034.x

Savvidou, C. (2010). Storytelling as Dialogue: how Teachers Construct Professional Knowledge. Teachers and Teaching, 16(6), 649–664. http://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2010.517682

Schmidt, M., & Knowles, G. J. (1994). Four Women’s Stories of ‘Failure’ As Beginning Teachers. (p. 40). Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New Orleans, LA. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/eric/docview/62708098/abstract/7F3F302A8BBA48C1PQ/1?accountid=17248

Scrivener, J. (1994). Learning Teaching: a Guidebook for English Language Teachers. Oxford: Heinemann.

Taeschner, T., Gheorghiu, I., & Colibaba, A. (2013). ‘The Narrative Format’for Learning and Teaching Languages to Children and Adults. Synergy, (2), 223–235.

Taguchi, K. (2006). Is Motivation a Predictor of Foreign Language Learning? International Education Journal, 7(4), 560–569.

Thornbury, S. (2001). Point and Counterpoint. The Unbearable Lightness of EFL. ELT Journal, 55(4), 391–396. http://doi.org/10.1093/elt/55.4.391

Turner, J. C., Christensen, A., Kackar-Cam, H. Z., Trucano, M., & Fulmer, S. M. (2014). Enhancing Students’ Engagement Report of a 3-Year Intervention With Middle School Teachers. American Educational Research Journal, 51(6), 1195–1226. http://doi.org/10.3102/0002831214532515

Turner, M. (1996). The Literary Mind. New York: Oxford University Press.

Vandergrift, L. (2005). Relationships Among Motivation Orientations, Metacognitive Awareness and Proficiency in L2 Listening. Applied Linguistics, 26(1), 70–89. http://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amh039

Vandergrift, L. (2007). Recent Developments in Second and Foreign Language Listening Comprehension Research. Language Teaching, 40(3), 191–210.

Walters, L. M., Green, M. R., Wang, L., & Walters, T. (2011). From Heads to Hearts: Digital Stories as Reflection Artifacts of Teachers’ International Experience. Issues in Teacher Education, 20(2), 37–52.

White, B. F. (1995). Effects of Autobiographical Writing before Reading on Students’ Responses to Short Stories. Journal of Educational Research, 88(3), 173–184.

Whittaker, C. R., Salend, S. J., & Duhaney, D. (2001). Creating Instructional Rubrics for Inclusive Classrooms. Teaching Exceptional Children, 34(2). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/eric/docview/1437904047/abstract/E2CE33D7361F4D35PQ/31?accountid=17248

Wilson, D. E. (1993). Composing Experience and Knowledge: Narrative as a Critical Instrument in English Teacher Preparation. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the National Council of Teachers of English, Pittsburgh, PA. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/eric/docview/62797112/abstract/6E90A3610CDE429EPQ/1?accountid=17248

Woodall, B. (2010). Simultaneous Listening and Reading in ESL: Helping Second Language Learners Read (and Enjoy Reading) More Efficiently. TESOL Journal, 1(2), 186–205. http://doi.org/10.5054/tj.2010.220151

Wright, A. (1995). Storytelling With Children. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wu, R. (1994). ESL Students Writing Autobiographies: Are There Any Connections? Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Rhetoric Society of America, Louisville, KY. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/eric/docview/62702220/abstract/9C6FA8564B3F4EB8PQ/1?accountid=17248

Yoshina, J. M., & Harada, V. H. (2007). Involving Students in Learning Through Rubrics. Library Media Connection, 25(5), 10–14.

Zamanian, M., & Heydari, P. (2012). Readability of Texts: State of the Art. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 2(1), 43–53.

Zaro, J. J., & Salaberri, S. (1995). Storytelling. Oxford: Heinemann.

Zeleke, A. S. (2013). Does Viewing Test Items at Different Times Matter in English for Academic Purpose Listening Test? Modern Journal of Language Teaching Methods, 3(2), 63–77.

Appendix A – Key new vocabulary in the stories

This appendix contains the key vocabulary in each story that the participants were likely to encounter for the first time. The prelistening phase introduced the key vocabulary.

Key vocabulary that was addressed in the prelistening phase of the autobiographical story: hiking, mountain range, tent, hut, sleeping bag, bunk beds, onigiri.

Key vocabulary that was addressed in the prelistening phase of the ELEANITZ story: magician, magic show, MC (master of ceremonies), worried, orchestra, audience, circus, clowns, jokes, troupe.

Appendix B – The autobiographical story

Hiking in Japan

A few summers ago, my husband and I spent six weeks in Japan, one of them hiking in the Japanese Alps, a long mountain range about 3,000 metres high.

The day before we started hiking, we prepared our rucksacks and filled them with all the things we would need: the tent, our sleeping bags, the little stove, water bottles, a bit of cutlery, the rain jackets, a few spare clothes, a bit of soap and our toothbrushes. And, of course, we needed food.

So, we went to the supermarket. Unfortunately, we spoke only a few words of Japanese, we couldn’t read anything, and we found nobody who spoke English. Everything looked very unfamiliar to us in the supermarket. We needed to take some sandwiches for lunch. But, guess what? Japanese people don’t eat bread, so we had to find something else. The closest thing to sandwiches is onigiri, rice balls. So, we bought onigiri and some cakes. My husband said: “I hope the mountain huts along the path will sell food. Otherwise, we will have to come down in two days, instead of seven.”

The next day we started hiking for seven days in the Japanese Alps. The first day was the hardest, because we had to climb almost 2,000 metres. We couldn’t read Japanese maps or signs, so we weren’t sure if we would find the path easily. Luckily, the path was very clear, so we didn’t get lost.

On this first day, we found a small mountain hut that sold food, where other Japanese hikers were buying noodles and onigiri. So, I thought: “Food will be easy to get along the way.”

Most days we slept in our tent, close to other hikers. We all got up at the same time in the morning, then started walking at a different pace, and we met again in the evening on the next campsite. So, they were our “tent-neighbours,” and we became friends with two of them, even if we couldn’t speak Japanese, and they didn’t speak English.

One afternoon, it started to rain, so we decided to go to a mountain hut, instead of sleeping in the tent. We had a nice supper, and slept on bunk beds. The next morning, we saw that the workers in the mountain hut were very nervous, walking up and down and talking on the radio. Finally, some other hikers came carrying on their shoulders a man who looked sick; his face was blue. His friends told us with signals that he had a heart attack. Then, we heard a helicopter, and we realised that it was coming to rescue the sick man. A man was dropped from the helicopter with a cable, he tied the sick man, and both of them were lifted up with the cable again.

After the rescue, it was sunny again. We left the mountain hut and continued with our walk. When we got to the next campsite, we met our two friends. That night we had dinner together, and we shared their barbeque meat and our onigiri, together with some sake they had. It was their last night in the Japanese Alps, and the same for us.

The next day we walked down another 2,000 metres, and said goodbye to our Japanese friends. I never learned their names, but we were friends for seven days.

Appendix C – Criteria followed to adapt input and to design the comprehension questionnaires

Listening comprehension is a very complex process. Much of its details remain unknown and, consequently, assessing it is also difficult. An effort was made to shape the autobiographical story in such a way that its degree of difficulty would be equal to that of the ELEANITZ story.

Nevertheless, the circumstances under which the empirical research took place made it impossible to take into account all the factors that could have been addressed (Révész & Brunfaut, 2013; Rubin, 1994) if there had been more time to analyse the degree of difficulty of the ELEANITZ story and adapt the autobiographical story to match it.

On the other hand, although the level or degree of difficulty of the listening activity will be set by the task itself, and not the material (Guariento & Morley, 2001; Scrivener, 1994; Wright, 1995), some of the factors determining task difficulty are related to text characteristics. In general, complexity of the language, cognitive load and performance conditions are considered the factors that should receive special attention in this sense (as cited in Guariento & Morley, 2001).

Regarding text difficulty, the following guidelines were taken into account to set the complexity of the language and the cognitive load in order to make input more comprehensible in the autobiographical story (Buck, 2001; Ellis & Brewster, 2002; Révész & Brunfaut, 2013; Rubin, 1994):

- Unfamiliar words were avoided, using more high-frequency vocabulary whenever it was deemed suitable, and idioms and keywords that might be unfamiliar were introduced before telling the story. Redundancy of words new to listeners was used throughout the narration.

- Regarding verb tense, the simple past was used. Structures were kept simple, and sentences short.

- Story events were referred in chronological order, following a linear order. In addition, wherever necessary, the sequence of events was reinforced using appropriate transition words (first, then, before etc.). Transition words were used to improve cohesion. Direct speech was used when it was thought it would make the story easier to follow. Finally, the number of events and people in the story was kept short.

- Additionally, while telling the story, visual aid was used to provide a schema-based approach and students were encouraged to ask for further clarification whenever they did not understand something in the story, in order to promote the negotiation of comprehensible input along the storytelling.

The comprehension questionnaires for the two stories were designed following the extensive analysis on listening assessment carried out by Buck (2001) and the review of further research literature on the subject published later on (Vandergrift, 2007). The following criteria were taken into account to design the comprehension questionnaires concerning task difficulty (Buck, 2001):

- The amount of information to be processed.

- The location of the information to be processed within the text, as integrating scattered information is more difficult.

- The type of content to be produced, as recalling literal content is easier than summarising.

- The relationship between the order of the questions and the order of the information in the story, because the task is easier when both are the same.

- The order of the questions in relation to their difficulty, as the task is easier when the questions are arranged starting from the easiest and progressing to the most difficult.

Appendix D – The questionnaires and the post-test survey

1. The autobiographical story

Set of questions regarding the autobiographical story:

- Whom did Miren go hiking with in the Japanese Alps?

- Her Japanese friend

- Her husband

- Her brother

- Her neighbour

- Which of the following did Miren put in her rucksack?

- A stove, a rain jacket, some deodorant

- Sunglasses, a tent, a bit of soap

- A water bottle, a hat, some spare clothes

- A sleeping bag, some cutlery, a toothbrush

- How much did Miren climb on her first day in the Japanese Alps?

- 1 000 metres

- 2 000 metres

- 3 000 metres

- 4 000 metres

- What was the story about?

- It was about the different types of food in Japan

- It was about the friends Miren made in Japan

- It was about Miren’s holidays in Japan and what happened to her in the Japanese Alps

- It was about a man who had a heart attack and had to be rescued in a helicopter

- Where did Miren get the food she ate during her days in the Japanese Alps?

- She bought everything in the supermarket

- She always ate in the mountain huts

- She got part in the supermarket and part in the mountain huts

- She got part in the supermarket, part in the mountain huts and part from her Japanese friends

- After having listened to this story, if you went to the Japanese Alps, which would be the most important three things you would put in your rucksack?

- A sleeping bag, a rain jacket and a bit of food

- A lot of food, some spare clothes and a toothbrush

- A tent, a sleeping bag and some soap

- A water bottle, some cutlery and a stove

- What do you think is the message of this story, the reason why Miren chose it? Why do you think that?

- Does this story remind you of anything that happened to you? Explain what happened shortly, please.

2. The story “Where's the magician?”

Set of questions on the story “Where's the magician?”:

- How did Peggy find out about the show of the Tilly Troupe?

- Her mum heard it on the radio

- Peggy read it on the school magazine

- Her mum read it on the newspaper

- David told Peggy about it

- Who called whom to go to the Tilly Troupe’s show?

- First, Peggy called David. Then, David called all the others

- Peggy’s mum called all her friends

- First, David called Peggy. Then, Peggy called all the others

- First, Peggy called David. Then, each called two friends

- When was the show going to start?

- At a quarter to five

- At five o’clock

- At a quarter past five

- At half past five

- Choose the sentence which best summarises the story

- The story was about a magician who got lost and didn’t arrive on time for the show

- The story was about Peggy and her friends, and what happened to them when they went to see the Tilly Troupe’s show

- The story was about Peggy and her friends, and how they organised to go to a show

- The story was about the clowns Coco and Jolly, who were making jokes and got cross in the end

- What had the Tilly Troupe planned to do in the show?

- The Tilly Troupe had planned to do magic tricks, clown jokes, and singing and dancing

- The Tilly Troupe had planned to play with the orchestra and dance

- The Tilly Troupe had planned to do horse riding tricks

- The Tilly Troupe had planned to do some clown jokes and magic tricks

- After having listened to this story, if you wanted to go to the Tilly Troupe’s show, what are the most important 3 things you would do before:

- Phone a friend, buy a ticket, and learn a joke

- Read the newspaper, arrive on time for the show, and learn a song

- Buy a ticket, arrive on time for the show, and learn a card trick

- Learn a card trick, a song and a joke

- Do you think the story is believable? Why do you think that?

- Has anything similar ever happened to you? Explain what happened shortly, please.

3. The post-test survey

- Which story did you like more?

- The story about Miren hiking in Japan

- “Where's the magician?”

- If your regular teacher, Idoia, asked you to summarise one of the stories in class, which would you choose? Why?

Appendix E – The Rubrics

This case study met two important criteria which supported using a rubric as the assessment tool for the comprehension questionnaires (Allen & Tanner, 2006; Andrade, 2005; Arter, 2000; Moskal, 2000a; Panadero & Jonsson, 2013): it dealt with a complex process – listening comprehension – which demanded a qualitative approach in the assessment, and it was intended to give the participants feedback on the results of the questionnaires in the form of a formative assessment, which would give them some guidance as to how to improve their listening comprehension. Rubrics are widely used in all stages of education, and they are not free of controversy, having both detractors (e.g. Kohn, 2006) and advocates (e.g. Livingston, 2012).

The rubric was partially designed in the form of an instructional rubric (Andrade, 2005; Whittaker et al., 2001). Unfortunately, the circumstances of the case study forced to use it as a scoring rubric.

The three local questions of each questionnaire were assessed with a holistic rubric, while the analytic rubric was considered more adequate to assess the four global questions, as each one of them dealt with a different aspect of comprehension. For the purpose of giving feedback to the participants, the rubric was slightly changed, in order to make it more self-explanatory. In particular, the holistic section of the rubric, which is applied to the first three questions, was turned into an analytic rubric. Besides, the language used in the rubric was reviewed in an attempt to bring it closer to student language, as suggested by Whittaker at al. (2001) and images were introduced to help communicate the contents.

The following pages contain the final rubrics, completely analytic and adapted in order to be handed out to the participants as feedback on the activities.

Appendix F – Comprehension scores per participant

The table in the following page shows the scores obtained by each participant in both stories.