The Cost of For-Profit Education: How Much is Your Degree Really Worth?

By

2015, Vol. 7 No. 03 | pg. 1/3 | »

IN THIS ARTICLE

KEYWORDS

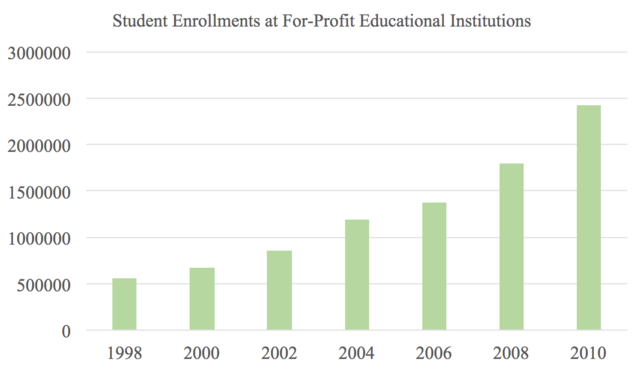

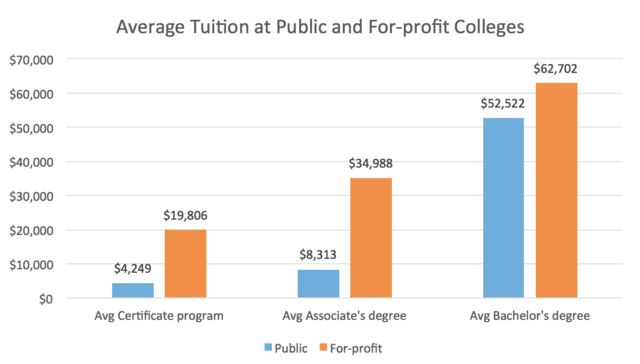

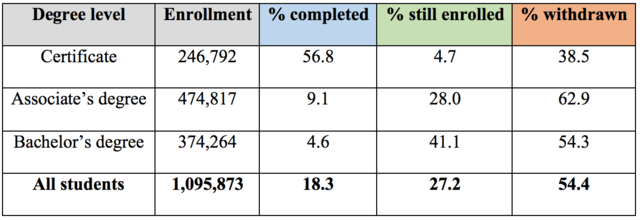

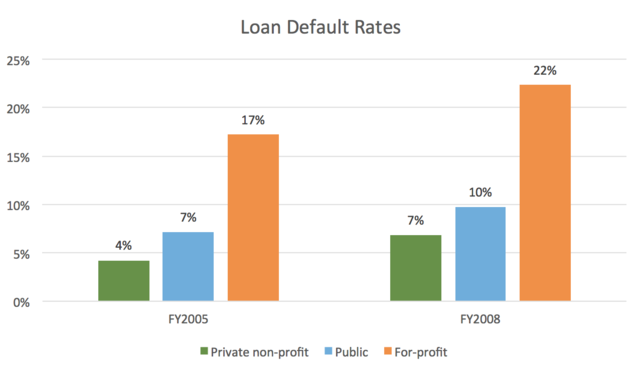

AbstractThis paper examines the latest attempt by the United States Department of Education to enact new regulations for addressing the issue of whether many post-secondary educational program offerings are appropriate in preparing students for gainful employment and under which conditions these programs can remain eligible for federal student financial aid. The proposed regulations are expected to affect mostly programs at for-profit educational institutions, though many state-supported institutions may be affected as well, thus making this a crucial issue for students and their equal opportunity access to post-secondary education. On March 14, 2014, the United States Department of Education released to the public a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking through which the administration is making known its proposal to amend federal regulations for addressing the issue of whether several post-secondary educational program offerings are appropriate in preparing students for gainful employment in a recognized occupation, and under which conditions these educational program offerings can remain eligible for student financial aid authorized under Title IV of the Higher Education Act of 1965 (U.S. Department of Education, 2014). The goal of this intended regulatory action by the federal government, which would take effect in 2016, is to address growing concerns that certain for-profit as well as non-profit institutions of higher education are currently using their Title IV eligibility to attract students into programs that do not effectively prepare them to enter the workforce as intended and which may leave graduates in considerable debt at a level not justified for the expected earnings of the career or occupation they invested in.This article explores the issue that brought about this proposed regulatory action by the U.S. Department of Education by first providing an overview of for-profit education in the United States and the growing numbers of students involved, and access, financial and academic issues of student enrollment at these institutions. Furthermore, related policy formation and regulatory background is also discussed in order to provide more context to the reader, as well as highlights of the proposed regulation, its expected outcomes and effects, and its possible intended and unintended consequences on all stakeholders. A Brief History of For-Profit EducationThe history of for-profit (and career colleges and universities in general) in the United States is not as recent as many would expect. Many in the education history arena are probably familiar with a private career college in the early 20th century founded in Rhode Island in 1911 by Katherine Gibbs, the Katherine Gibbs School; the school was established as an opportunity for young women to obtain or improve skills necessary for successful secretarial positions. The school was in existence for almost a century when it was acquired in 1997 by one of the largest for-profit education corporations in the country, Career Education Corporation. Another well-known for-profit institution of higher education in the United States is Apollo Group’s University of Phoenix; founded in 1976, it is best known for its many online programs. The University of Phoenix is currently the second largest institution by total enrollment in the country (Tierney, 2011). Other well-known for-profit educational institutions include DeVry University, Educational Management Corporation, Washington Post’s Kaplan University, Bridgepoint Education, and Corinthian Colleges (Winston, 1999) Even though the for-profit career sector has been existing in parallel to traditional educational institutions for a century, only relatively recently, with the tremendous growth the sector has experienced, has the sector been on the forefront of education policy (Wilson, 2010). Post-secondary career education has grown dramatically in the last decade, with enrollments almost quintupling in the span of approximately ten years (Figure 1). Federal and state mandates of increased access to higher education coupled with the availability of federal financial aid (and possible lack of accountability by the sector) are, according to some researchers, some of the likely factors for the tremendous growth experienced in recent years (Darolia, 2013, John, Daun-Barnett, & Moronski-Chapman, 2013) as well as the proliferation of compliance and accountability issues that the U.S Department of Education aims to address in its proposed regulatory action. Figure 1: Student enrollments at for-profit educational institutions Source: U.S. Department of Education Education Access Through Financial AidIn recent years, there has been a lot of publicity, usually negative, about for-profit post-secondary educational organizations, the largest of which are large corporations as mentioned earlier, some public and some private, operating multiple separately branded colleges and universities with multiple campuses throughout the United States. There seems to be a common misconception in all this rhetoric, writes Richard Hassler (2006), that these institutions aim to provide the same high-level intellectual service to students as traditional universities. As proof, Hassler (2006) and Wilson (2010) point out that the mission of these organizations is different than what is reported, usually found in these organizations’ mission statements as targeting those students who wish to learn skills necessary for career fields currently in demand and usually targeted for working adults. Certainly, a point can be made that such post-secondary educational institutions provide wider access to higher education to a population of diverse socio-economic or professional backgrounds (Bailey, Badway, & Gumport, 2001). That access of course comes at a high cost for those students who chose to widen their educational achievements through for-profit institutions (Denice, 2012). Such costs are usually alleviated through the use of financial aid, much of which comes from the federal government under Title IV of the Higher Education Act of 1965 (United States Department of Education, 2014). The government currently provides $26 billion in federal loans and $10 billion in grants annually to schools that prepare students for gainful employment, according to the U.S. Department of Education officials (Reuters, March 13, 2014). According to the same officials, the vast majority of that funding goes to for-profit institutions that attract students with extensive marketing campaigns promoting their eligibility to award federal financial aid. Cellini (2010) also supports the notion that increasing availability of federal financial aid encourages new for-profit universities to enter the market since these funds can be used at any Title IV institution. Education for Gainful Employment or Just Selling a Product?Admittedly, for-profit educational institutions do not necessarily aim to provide the same intellectual product that traditional colleges and universities do. Many of the for-profit institutions provide educational programs that are largely tailored to working adults seeking a degree to improve their professional and economic status as the value of a high-school diploma can no longer suffice for a middle-class life. To that extent, there is a noticeable degree of marketing for educational programs offered at such institutions to the point where one wonders whether these institutions, whose bottom line is the attainment of profit for the owners and/or their shareholders, are not actually creating the perceived demand for expensive post-secondary education via extensive marketing campaigns (Cellini, 2012). A U.S. Senate investigation by the Health, Education, Labor and Pensions (HELP) committee (2012) revealed that tuition costs at for-profit colleges and universities are much higher than those at public institutions (Figure 2). Admissions practices are often found irregular, true costs of the product advertised may not be well explained by admissions counselors or well understood by potential students, while eighty to ninety percent of students rely on financial aid in order to attend. These are only some of the issues that exist in many for-profit institutions (Tierney, 2011). Figure 2: Average tuition cost comparison of public and for-profit educational institutions Source: Senate HELP committee report. Without a doubt the reason for attending a post-secondary educational institution is to gain or improve skills that lead to a certain professional position. In general, the term “gainful employment” has been used to describe the potential of an individual to provide a service or produce a product for which payment is received. It is legally defined in Title 34 of the Code of Federal Regulations, also known as 34 CFR 668.7 (U.S. Department of Education, 2014) where minimum quantifiable standards are also given specifically as they relate to gainful employment as a result of an educational program or training. The March 14, 2014, Notice of Proposed Rulemaking by the U.S. Department of Education aims exactly at addressing these standards for determining whether post-secondary educational program offerings under the gainful employment category enable students to enter substantially gainful employment as a result of their program of study, and under which conditions these educational program offerings can be continue to be considered eligible for student financial aid authorized under Title IV of the Higher Education Act of 1965 (U.S. Department of Education, 2014). Prior Regulatory ActionIn order to address issues with the gainful employment mandate of Title IV of the Higher Education Act of 1965 and the proliferation of educational programs that allegedly do not offer the expected outcomes, the U.S. Department of Education attempted to amend federal regulations in June 2011 in a Rule that applied to most programs of study at for-profit institutions as well as non-degree-granting programs at both non-profit and public post-secondary institutions. The Department of Education’s authority for this regulatory action is derived primarily from three sources, which are discussed in more detail in “§668.401 Scope and purpose” and “§668.403 Gainful employment framework” of part 668 of Title 34 of the Code of Federal Regulations (U.S. Department of Education, 2014); however, a first attempt to impose rules similar to those described in the 2014 Notice of Proposed Rulemaking has already been struck down in the court system in 2012 (Reuters, 2014, March 13). Traditionally, proposed regulations are developed without any input from the public but published in the Federal Registry upon completion for public comments. These published documents are known as Notices of Proposed Rulemaking. Unlike typical approach, the Department is required by law to specifically employ negotiated rulemaking to develop policies authorized under the Title IV of the Higher Education Act of 1965 (unless deemed impractical or contrary to public interest). In negotiated rulemaking, stakeholders of policies sought to be developed are included in a series of meetings through their representatives and work with the Department to reach a consensus on the proposed rules (U.S. Department of Education, 2014). If no consensus is reached the Department may decide to convene a new series of meetings or move at its discretion and enact part of all of the regulations under discussion. The enactment of such policy was opposed by the Association of Private Sector Colleges and Universities (APSCU), an organization of voluntary membership of accredited, private, post-secondary, career colleges and universities of approximately 1,400 member institutions (Association of Private Sector Colleges and Universities, 2014a). Neither the Association, nor any of its member institutions were invited to take part in the negotiated rulemaking process. The Association filed legal action against the U.S. Department of Education to overturn the new regulations. It contended that the U.S. Department of Education had exceeded its authority in issuing the new regulations and that it had arbitrarily set the benchmarks that institutions would be required to meet in order to remain eligible to receive federal financial student aid. The Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit where the case was heard eventually granted relief under all new regulations on June 5, 2012, for lack of a reasoned basis, hence being deemed as arbitrary. The ruling did affirm though the U.S. Department of Education’s authority to issue such regulations and advocated for new guidelines to be established (Blumenstyk & Huckabee, 2012). The U.S. Department of Education was not alone feeling dismayed at the court’s ruling on this matter. Other organizations that were in favor of imposing stricter standards on for-profit educational institutions were also upset, as the following quote by Pauline Abernathy, Vice President of the Institute for College Access & Success indicates: "the decision issued this weekend leaves students and taxpayers alike exposed to unscrupulous schools that seek to swindle them and routinely saddle students with debts they cannot repay" (Blumenstyk & Huckabee, 2012). Abernathy’s claims may have factual basis according to a 2012 investigation by the Health, Education, Labor and Pensions (HELP) committee (U.S. Senate, 2012) which found that students attending for-profit colleges and universities end up defaulting on financial aid loans much more frequently that those students attending other types of institutions, public or private non-profit institutions (Figure 3), without necessarily having increased graduation rates. The average completion rate of students enrolled at for-profit institutions in the data for the 2008-2009 academic year was only 18.1 percent while the average withdrawal rate in the same year was 54.4 percent (Table 1). Some for-profit institutions had withdrawal rates as high as 84 percent of their student population, according to the same report (U.S. Senate, 2012). Because of such issues, the U.S Department of Education attempted to set related benchmarks to prevent institutions not meeting these benchmarks being eligible for federal financial student aid, which the June 5, 201figure2 court ruling found arbitrary. Table 1: Status of students enrolled in for-profit education companies (2008–2009) by degree. Source: Senate HELP committee report On the opposite side of the judicial struggle, the ruling was seen as the most correct and appropriate decision the court could make, and a spokesman for Corinthian Colleges argued that the ruling proves that for-profit institutions were not just complaining out of self-interest; Corinthian Colleges serve more than eighty thousand students, and would stand to lose seven percent of its programs by failing the U.S. Department of Education’s new regulation benchmarks should it were enacted (Blumenstyk & Huckabee, 2012). Steve Gunderson, president of the California Association of Private Postsecondary Schools (CAPPS), a large and the only such advocacy organization in the state of California, having over three hundred member institutions, also expressed his appreciation for the court’s ruling writing in a statement that “we won an important victory” (California Association of Private Postsecondary Schools, 2012). Figure 3: Loan default rates of private non-profit, public, and for-profit educational institutions. Source: Senate HELP committee report. The U.S. Department of Education appealed the court’s decision to strike down the regulation, but its appeal was denied in March 2013. Instead of proceeding with further litigation, the Department of Education decided to convene a new negotiating panel to decide on a new set of standards by the end of the year. None of the for-profit institutions or their representative trade organizations were invited to participate. The Association of Private Sector Colleges and Universities said in a written statement that the meeting was “stacked with individuals opposed to the very existence of our institutions” (Stratford & Fain, 2013). The negotiating panel, without representation from for-profit institutions, was not able to reach a consensus on the new standards as mandated, therefore leaving the Department of Education with the task of re-attempting to establish new regulation in the same manner as it initially did in 2011 (American Council on Education, 2014).Continued on Next Page » Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in Education |