The First World War is largely thought of as a conflict where the majority of the significant operations took place almost exclusively on mainland Europe with the exception of a handful of naval clashes fought throughout the world's oceans. This is only partially true because while most of the fighting did take place on the continent, one of the largest and most sophisticated undertakings of the war was conducted mainly at sea. This operation was the British blockade from 1914-1919 which sought to obstruct Germany's ability to import goods, and thus in the most literal sense starve the German people and military into submission.

While the land war certainly contributed to the Entente's (Britain, France, Italy, U.S.) victory in 1918, it was the blockade that truly broke Germany's back. Without it, the war could have potentially gone on even longer, but because of it, the world's preeminent land force was left with no other choice than to surrender as the seeds of revolution brewed among its population. This paper will look into how this important British undertaking functioned, how it affected the German people, and how it played a significant role in causing the German military to sue for peace in 1918.

The British blockade of Germany from 1914-1919 was one of the largest and most complex undertakings attempted by either side during the First World War. While Britain employed considerable resources in other areas of the conflict, the blockade became the source of the United Kingdom's greatest efforts during the war. As Eric Osborne noted, "It is true that the exploits of the British Army and Royal Navy aided greatly in the conflict, but Britain's greatest contribution to the allied cause was the largely unseen economic pressure occasioned by naval supremacy through the imposition of a blockade of Germany."

This of course was Britain's traditional area of expertise, and something they had used considerably in the past. The British mindset was summed up by Greg Kennedy when he noted that Britain's two major allies - France and Russia - possessed large modern armies that were best suited to conducting a land war. Britain conversely maintained the world's largest navy, but had only limited trained land forces available. Thus the British could best direct their efforts to blockading Germany at sea, while providing smaller numbers of troops on the continent to help bolster the western front.

The best place to begin research of the blockade is with the early planning that took place before the war began. Most historians agree that planning began in 1904, when British Prime Minister Sir Arthur Balfour duly recognized that the rapidly growing German navy was in part being constructed to challenge British naval supremacy. During his last year in office, he set out to address this threat by advocating for the build up of a large naval fleet to be based in the North Sea.

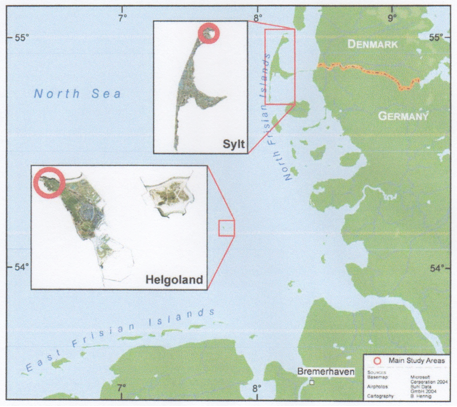

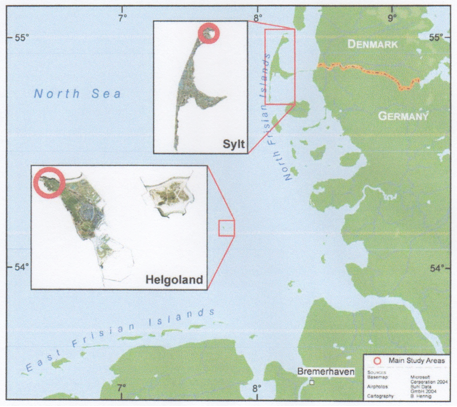

This flotilla's main task would be to hold Germany's new modern navy in check, and defending the home island should both countries find themselves at war with one another. The plans for the blockade then developed over the course of the next ten years in three distinct stages beginning with the early plan known as the 'close blockade.' The first goal here was to capture the two key German islands Sylt and Heligoland in the North Sea, and use them as observation posts. The main British fleet would be positioned 170 miles back to guard against craft attempting to reach German ports, or the German High Seas Fleet from breaking out of its bases in Wilhelmshaven, Kiel or other Northern European bases (see Figure 1.1 in appendix).

This plan later changed in 1912 when naval planners observed that both islands had been severely fortified, and that Germany now possessed growing fleets of submarines and torpedo boats that could easily slip the blockade. British planners particularly feared such threats because the United Kingdom depended on the constant uninterrupted flow of trade to feed its population, and to make profits from trading its primary natural resources such as coal, iron, and tin.

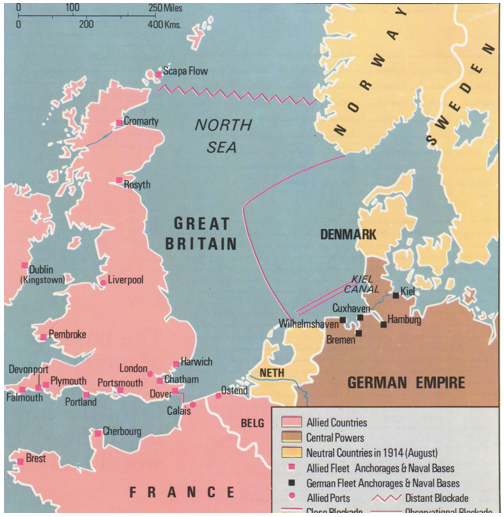

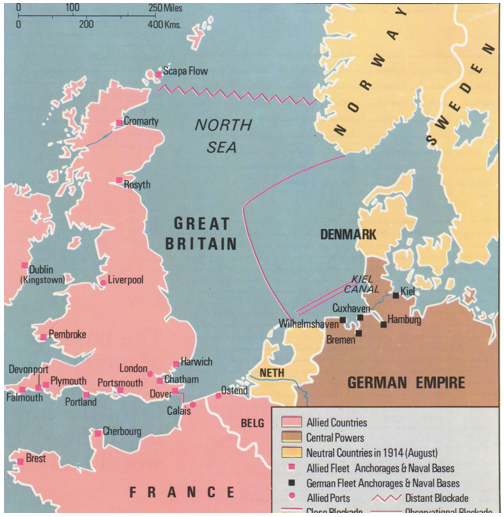

Thus Royal Navy planners recognized early that neutralizing the German navy from the outset, and preventing them from forming their own blockade of the United Kingdom, was the key to ensuring their own survival and success in the war. The new plan, designated as the 'observational blockade,' placed fast moving cruisers and destroyers from the southwestern tip of Norway to the center of the North Sea, and then down south to the coast of Holland. The Grand Fleet would once again be stationed further back ready to intercept the High Seas Fleet, and watch for merchant ships attempting to slip the blockade (see Figure 1.2 in appendix).

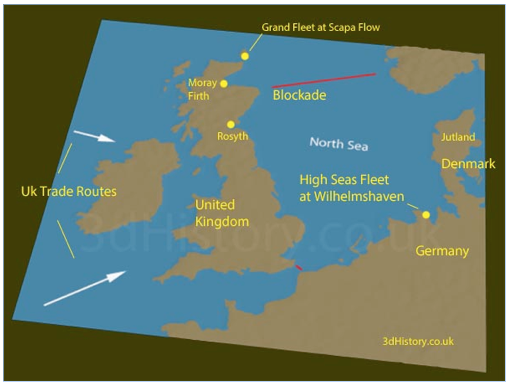

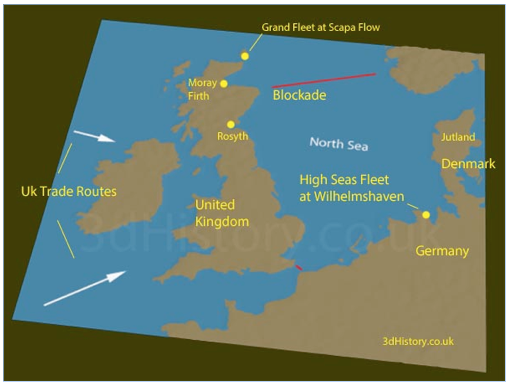

This second strategy was finally revised one last time in July, 1914. The observational blockade became the 'distant blockade.' In this final revision, the two entrances into the North Sea were blockaded first between the Dover Straits and northern France, and then between Norway and Scotland (see Figure 1.3 in appendix). As Kemp noted, this final operational change was described in the new official War Plan as to have the movement of ships "be sufficiently frequent enough and sufficiently advanced to impress upon the enemy that he cannot at any time venture far from his home ports without such serious risk of encountering an overwhelming force." The distant blockade thus covered two operational concerns - stopping merchant ships from reaching German ports, and giving German Naval leaders visual stimuli that should they set sail, it was at their own peril.

It is easy to assume that the British simply placed ships in strategic locations and waited for craft containing contraband to approach; or for Germany's High Seas Fleet to try escape the North Sea confines. The truth is much more complicated than that because the blockade was conducted on more than just the world's vast oceans. In reality the blockade was not even entirely a product of the Royal Navy. As Greg Kennedy contends, the blockade was only executed by the Royal Navy, but was administered and guided by the British Foreign Office (FO).

It was the politicians who entered into negotiations with neutral states to win them to the Entente cause, or at the very least to convince them to terminate trade with Germany and its allies. It was also governmental committees that studied statistics complied by thousands of clerks and analysts, and indexed materials to be targeted by the navy so that Germany could be denied what it needed the most.

Spies and other ground assets were also an essential piece of the puzzle that kept the blockade running at peak efficiency. Each individual was tasked with finding which merchants were transporting contraband to the enemy, and what routes they would be taking so that the Royal Navy could be intercept them before they reached their port of call. These agents then reported back to Room 40 - the British Admiralty's intelligence analyzing and planning section - on anything suspicious, and if need be, set in motion the rest of the blockade apparatus based on their information.

Kennedy argued that it was this sector of the blockade that was most important because key decisions were made at every other level based on information provided from ground assets. Without these operatives the British would have been blind to how best to apply the rest of their resources. Thus the blockade lived and died with good intelligence flowing into the United Kingdom.

When Britain joined the war on August 4, 1914, they did not immediately execute the entire plan to blockade all German imports. It was not until nearly four months into the war that Britain labeled the North Sea a war zone, and also began directing limited forces in the Mediterranean as well to restrict all German trade routes. In spite of this fact, British intelligence apparatus began the long process of accumulating data on where the Germans were obtaining their goods from, and analysts compiling this data into reports so that the Royal Navy could quickly cut all avenues of trade once the full blockade was established.

A part of the reasoning for the delay in full action was due to the U.S. government's insistence that all belligerents respect neutral rights of free trade, and not impede enemy merchants from reaching their destinations if they were transporting only civilian supplies. These rights had been discussed during the second Hague International Peace Convention in 1907, and set fourth in a legal document at the International Naval Conferences in London in 1909. This document became known as the Declaration of London, and was signed by all major belligerents that were to fight in WWI, but was only ratified by the United States. The most notable country that did not ratify the declaration document was Britain.

They refused to do so because Britain's leaders could not agree on several passages including the rights of neutrals to transport goods to their own home ports, even when they knew these materials would be sold to the enemy. Even so, Britain was in a precarious situation because while they did not legally have to follow the declaration, the U.S. expected them to do so. It was paramount that Britain tread lightly in this grey area of legality because as Siney noted, it was evident from the beginning of the war that the U.S. would be the principle supplier of financial capital and munitions to the Entente during the war. Therefore instituting a full blockade of Germany imports when war broke out could have been the death knell not for Germany, but for Britain and its allies.

The final shift to establishing the full blockade came on November 11, 1914, after several German light cruisers were observed attempting to lay mines off the coast of southern England. This act of aggression gave British leaders the impetus they needed to declare the full blockade without U.S. resistance because during the first four months of the war, Britain had confined itself to blocking only war materials from reaching German ports. World opinion of Germany during this time began to deteriorate because of repeated reports of brutality directed against Belgian and French civilians. With world sympathies firmly shifting in the Entente's favor, Britain gained the necessary advocacy it needed to declare its right to institute the blockade, and defend its realm against the aggressive German empire.Continued on Next Page »

"Battle and Conflict; The Schlieffen plan" Anglia-campus, http://www.jeron.je/anglia/learn/sec/history/ww1/page07.htm

Becker, Jean-Jacques, The Great War and the French People. Providence & Oxford: Berg, 1985.

Belinda Davis, Food Politics, and Everyday Life in World War I Berlin: Home Fires Burning. Chapel Hill & London: University of North Carolina Press, 2000.

Blum, Matthias. "Government Decisions Before and During the First World war and the Living Standards in Germany During a Drastic Natural Experiment" In Exploration in Economic History. 48-4. 2011.

Churchill, Winston. The World Crisis. New York: Free Press, 1931.

Munro, Dana, Sellery, George and Krey, August, German Treatment of Conquered Territory. Washington: The Committee on Public Information, 1918.

Englander, David The Oxford Illustrated History of the First World War. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Phillips, Ethel "American Participation in Belligerent Commercial Controls 1914-1917," In American Society of International Law, 27-4. 1933.

Ferguson, Niall, The Pity of War. Great Britain: The Penguin Group, 1998.

Fritzsche, Peter, Germans into Nazis. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998.

Schreiner, George The Iron Ration Three Years in Warring Central Europe, New York & London: Harper & Brothers Publishing, 1918.

Hancock W.K., and Van Der Poel Jean, Selections from the Smuts Papers: Volume IV November 1918-August 1919. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Hennig, Benjamin. "Applications of hyperspectral remote sensing in coastal ecosystems: A case study from the German North Sea." http://www.hennig-online.net/benjamin/

Hillgruber, Andreas. The Marshall Cavendish Illustrated Encyclopedia of World War 1. New York: Marshall Cavendish Corporation, 1984.

History of World War I. Tarrytown: Marshall Cavendish Corporation, 2002.

Kemp, Peter, The Marshall Cavendish Illustrated Encyclopedia of World War 1. New York: Marshall Cavendish Corporation, 1984.

Kennedy, Greg. "Intelligence and the Blockade, 1914-1917: A Study in Administration, Friction and Command." In Intelligence and National security. No. 5. October 2007.

Kunkel B.W., "Calories and Vitamines," The Scientific Monthly, 17-4. 1923.

Lohr, Eric, A call to Arms: Propaganda, Public Opinion, and Newspapers in the Great War, WestPort: Praeger Publishers, 2004.

McDermott, John. "Trading With the Enemy: British Business and the Law During the First World War." In Canadian Journal of History/Annales canadiennes d'histoire XXXII, August, 1997.

"Memorandum to the War Cabinet on Trade Blockade." United Kingdom National Archives, Note 2. 1917. http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/firstworldwar/spotlights/blockade.htm

Miles Bouton, And The Kaiser Abdicates. New haven: Yale University Press, 1920.

Molodowsky, N "German Foreign Trade Terms in 1899-1913." In The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 41-4. August, 1927.

Murray Rothbard, Herbert Hoover - The Great War and Its Aftermath. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1979.

O'Brien, Patrick. "The Economic Effects of The Great War." In History Today. No. 12. December, 1994.

Offer, Avner. The First World War: An Agrarian Interpretation. New York & Oxford: Clarendon Press; Oxford University Press, 1989.

Osborne, Eric. Britain's Economic Blockade of Germany 1914-1919. London & New York: Frank Cass, 2004.

Richter Lina, Family Life In Germany under The Blockade. London: National Labour Press Limited, 1919.

Shaw, Bernard. Family Life in Germany Under the Blockade. National Labour Press Limited: London, 1919.

Siney, Marion. The allied blockade of Germany 1914-1916. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1957.

Strachan, Hew. The First World War. New York: Penguin Books, 2005.

Tomes Jason, Balfour and foreign policy - The International Thoughts of a Conservative Statesman. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Tuchman, Barbara, The Guns of August. New York: Macmillan, 1962.

Van Der Kloot, William. "Ernst Starling's Analysis of the Energy Balance of the German People During the Blockade 1914-1919." In Notes and records of the Royal Society of London. 57-2. May, 2003.

Vincent, Paul The Politics of Hunger: The Allied Blockade of Germany 1915-1919. Athens, Ohio London: Ohio University Press, 1985.

Virneth Studios Ltd, "The Battle of Jutland 31st May 1916 - Background." 3D History, http://www.3dhistory.co.uk/ww1/naval-warfare/jutland-backgound.php.

Zweiniger-Bargielowska Ina, Duffett Rachel, and Drouard Alain, Food and War in Twentieth Century Europe. Burlington: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2001.

Appendix

Appendix A

Figure 1. Location of German islands Heligoland and Sylt

Source: Hennig, Benjamin. hennig-online.net, "Applications of hyperspectral remote sensing in coastal ecosystems: A case study from the German North Sea ." Last modified 2007. Accessed October 1, 2013. http://www.hennig-online.net/benjamin/.

Appendix B

Figure 2. Location of Royal Navy 'observational blockade' plan 1912.

Source: The Marshall Cavendish Illustrated Encyclopedia of World War 1 (New York: Marshall Cavendish Corporation, 1984): 177.

Appendix C

Figure 3. Site of Royal Navy 'distant blockade' plan established 1914-1919

Source: Virneth Studios Ltd "The Battle of Jutland 31st May 1916 - Background." Accessed September 30, 2013. http://www.3dhistory.co.uk/ww1/naval-warfare/jutland-backgound.php.

Appendix D

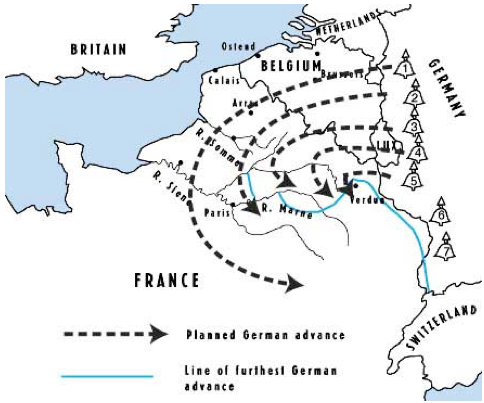

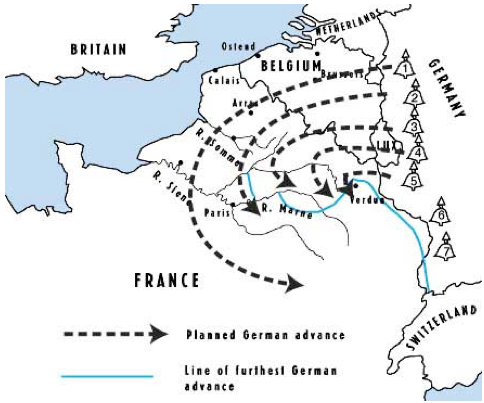

Figure 4. Schlieffen plan as executed on the western front in August 1918.

Source: "Battle and Conflict; The Schlieffen plan" Accessed October 13, 2013. http://www.jeron.je/anglia/learn/sec/history/ww1/page07.htm

Appendix E

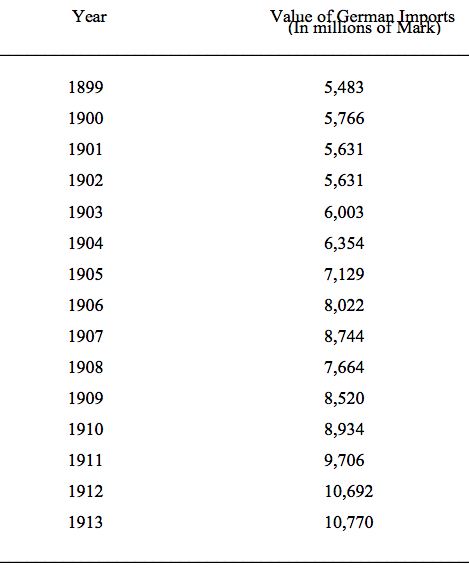

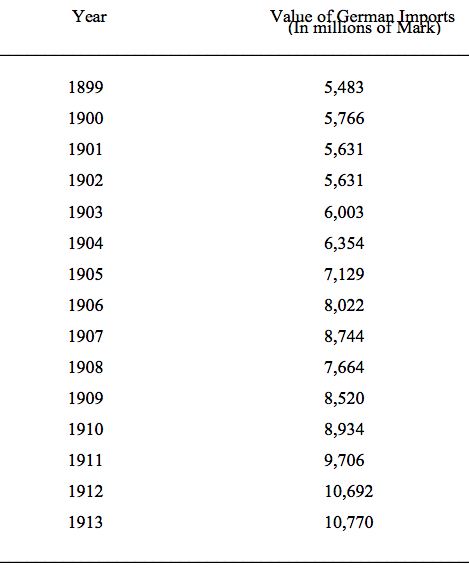

Table 2.1. German import statistics from 1899-1913

Source: Molodowsky N. "German Foreign Trade Terms 1899-1913" The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 41, no. 4 (Aug 1927): 666.

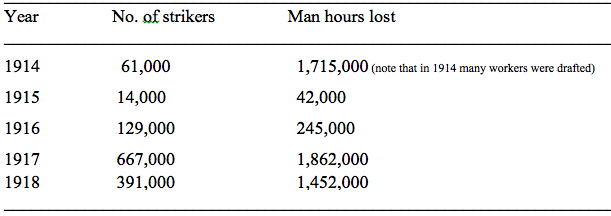

Appendix F

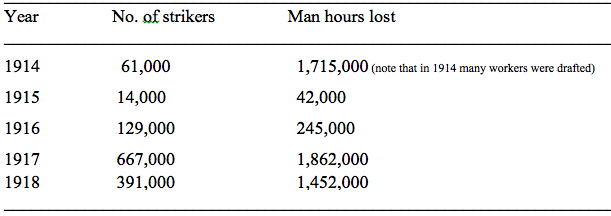

Table 2.2. Strikes in Germany 1914-1918

Source: Ferguson, Niall, The Pity of War (Great Britain: The Penguin Group, 1998): 275

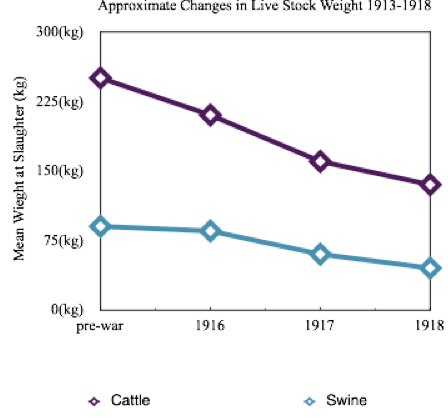

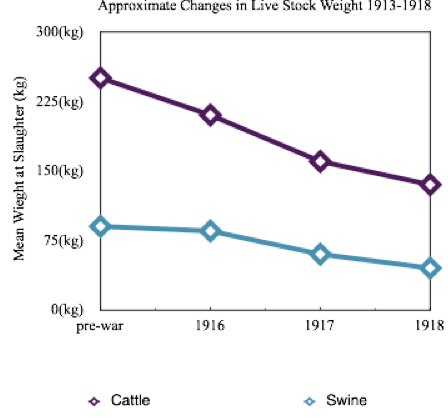

Appendix H

Figure 6 Weights of German Farm animals when slaughtered 1913-1918.

Source: Van Der Kloot, William. Ernst Starling's Analysis of the Energy Balance of the German People During the Blockade 1914-1919." Notes and records of the Royal Society of London. Vol. 57, No. 2 (May 2003): 189.

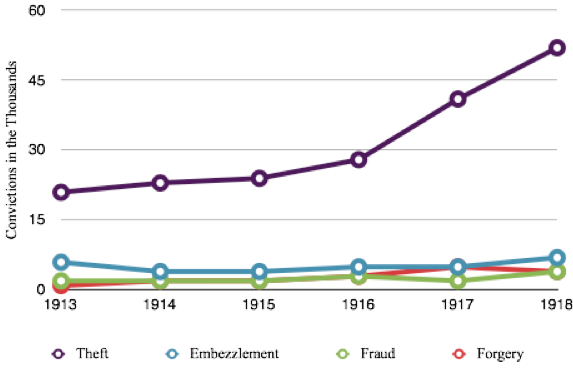

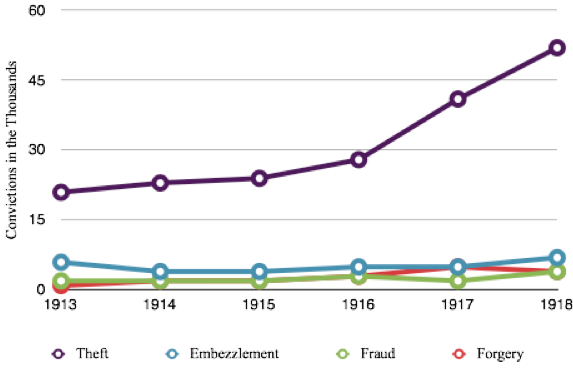

Appendix I

Table 1.3 Women convicted of crimes 1913-1918

Source: Belinda Davis, Food Politics, and Everyday Life in World War I Berlin: Home Fires Burning, (Chapel Hill & London: University of North Carolina Press, 2000), 223.

Endnotes

1.) Osborne, Eric. Britain's Economic Blockade of Germany 1914-1919, (London & New York: Frank Cass, 2004), 1.

2.) Kennedy, Greg. "Intelligence and the Blockade, 1914-1917: A Study in Administration, Friction and Command." Intelligence and National security. no. 5 (Oct. 2007): 700.

3.) Tomes Jason, Balfour and foreign policy - The International Thoughts of a Conservative Statesman, (Cambridge : Cambridge University Press, 1997), 133-134.

4.) Kemp, Peter, The Marshall Cavendish Illustrated Encyclopedia of World War 1, (New York: Marshall Cavendish Corporation, 1984): 182.

5.) Kemp Peter, The Marshall Cavendish Illustrated Encyclopedia of World War 1, (New York: Marshall Cavendish Corporation, 1984): 182.

6.) Ibid., p. 182.

7.) Kennedy, Greg. "Intelligence and the Blockade, 1914-1917: A Study in Administration, Friction and Command." Intelligence and National security. no. 5 (Oct. 2207): 701.

8.) Ibid., p. 710.

9.) Ibid., p. 716.

10.) Siney, Marion. The allied blockade of Germany 1914-1916. The University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor. (1957): 24.

11.) McDermott, John. "Trading With the Enemy: British Business and the Law During the First World War." Canadian Journal of History/Annales canadiennes d'histoire XXXII. (Aug 1997): 202-203.

12.) Ibid., p. 209.

13.) Ibid., p. 210.

14.) O'Brien, Patrick. "The Economic Effects of The Great War." History Today. no. 12 (Dec. 1994): 22.

15.) Siney, Marion. The allied blockade of Germany 1914-1916. The University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor. (1957): 34.

16.) Ethel Phillips, "American Participation in Belligerent Commercial Controls 1914-1917," American Society of International Law, 27, no. 4 (1933): 684.

17.) Kennedy, Greg. "Intelligence and the Blockade, 1914-1917: A Study in Administration, Friction and Command." Intelligence and National security. no. 5 (Oct. 2207): 709-710.

18.) Ibid., p. 686.

19.) Strachan, Hew. The First World War. New York: Penguin Books. (2005) 217.

20.) United Kingdom National Archives, "Memorandum to the War Cabinet on Trade Blockade ." Note 2. Accessed September 15, 2013. http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/firstworldwar/spotlights/blockade.htm.

21.) Ibid., Note 2.

22.) Ibid., Note 3.

23.) Molodowsky, N "German Foreign Trade Terms in 1899-1913," The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 41, no. 4 (Aug 1927): 666.

24.) Ibid., p. 688.

25.) Van Der Kloot, William. "Ernst Starling's Analysis of the Energy Balance of the German People During the Blockade 1914-1919." Notes and records of the Royal Society of London. Vol. 57, No. 2 (May 2003): 187.

26.) Paul Vincent, The Politics of Hunger: The Allied Blockade of Germany 1915-1919, (Athens, Ohio London: Ohio University Press, 1985), 5.

27.) Tuchman, Barbara, The Guns of August, (New York: Macmillan, 1962), 20.

28.) Ibid., p. 21.

29.) Ibid., p 128-129.

30.) Kunkel, B.W. "Calories and Vitamines," The Scientific Monthly, 17, no. 4 (1923): 364,

31.) Van Der Kloot, William. "Ernst Starling's Analysis of the Energy Balance of the German People During the Blockade 1914-1919." Notes and records of the Royal Society of London. Vol. 57, No. 2 (May 2003): 189.

32.) Richter Lina, Family Life In Germany under The Blockade, (London: National Labour Press Limited, 1919), 21.

33.) Vincent, Paul The Politics of Hunger: The Allied Blockade of Germany 1915-1919, (Athens, Ohio London: Ohio University Press, 1985), 21.

34.) George Schreiner, The Iron Ration Three Years in Warring Central Europe, (New York and London: Harper & Brothers Publishing, 1918), 174.

35.) N/A, History of World War I, (Tarrytown: Marshall Cavendish Corporation, 2002), 658.

36.) Ibid., p. 665.

37.) Strachan, Hew. The First World War. New York: Penguin Books. (2005) 218.

38.) Ibid., p. 218.

39.) Ibid., p. 218.

40.) Churchill, Winston The World Crisis, (New York: Free Press, 1931), 686.

41.) Siney, Marion. The allied blockade of Germany 1914-1916. The University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor. (1957): 47.

42.) United Kingdom National Archives, "Memorandum to the War Cabinet on Trade Blockade ." Note 1. Accessed September 15, 2013. http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/firstworldwar/spotlights/blockade.htm.

43.) Strachan, Hew. The First World War. New York: Penguin Books. (2005) 215.

44.) Van Der Kloot, William. "Ernst Starling's Analysis of the Energy Balance of the German People During the Blockade 1914-1919." Notes and records of the Royal Society of London. Vol. 57, No. 2 (May 2003): 189-190.

45.) Vincent, Paul The Politics of Hunger: The Allied Blockade of Germany 1915-1919, (Athens, Ohio London: Ohio University Press, 1985), 138.

46.) Richter Lina, Family Life In Germany under The Blockade, (London: National Labour Press Limited, 1919), 32.

47.) Vincent, Paul, The Politics of Hunger: The Allied Blockade of Germany 1915-1919, (Athens, Ohio London: Ohio University Press, 1985), 137.

48.) Ibid., p. 128.

49.) Richter Lina, Family Life In Germany under The Blockade, (London: National Labour Press Limited, 1919), 22.

50.) Vincent, Paul The Politics of Hunger: The Allied Blockade of Germany 1915-1919, (Athens, Ohio London: Ohio University Press, 1985), 128.

51.) Miles Bouton, And The Kaiser Abdicates, (New haven: Yale University Press, 1920), 73.

52.) Richter Lina, Family Life In Germany under The Blockade, (London: National Labour Press Limited, 1919), 29.

53.) Ibid., p. 45.

54.) Ibid., p. 45-46.

55.) Zweiniger-Bargielowska Ina, Duffett Rachel, and Drouard Alain, Food and War in Twentieth Century Europe, (Burlington: Ashgate Publishing Limited , 2001), 15.

56.) Van Der Kloot, William. "Ernst Starling's Analysis of the Energy Balance of the German People During the Blockade 1914-1919." Notes and records of the Royal Society of London. Vol. 57, No. 2 (May 2003): 190.

57.) Miles Bouton, And The Kaiser Abdicates, (New haven: Yale University Press, 1920), 73.

58.) Dana Munro, George Sellery, and August Krey, German Treatment of Conquered Territory , (Washington : The Committee on Public Information , 1918).16-17.

59.) Vincent, Paul The Politics of Hunger: The Allied Blockade of Germany 1915-1919, (Athens, Ohio London: Ohio University Press, 1985), 131.

60.) Belinda Davis, Food Politics, and Everyday Life in World War I Berlin: Home Fires Burning, (Chapel Hill & London: University of North Carolina Press, 2000), 201.

61.) Murray Rothbard, Herbert Hoover - The Great War and Its Aftermath, (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1979), 93.

62.) Belinda Davis, Food Politics, and Everyday Life in World War I Berlin: Home Fires Burning, (Chapel Hill & London: University of North Carolina Press, 2000), 210-211.

63.) Ibid., p. 210

64.) Fritzsche Peter, Germans into Nazis, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998), 31.

65.) Belinda Davis, Food Politics, and Everyday Life in World War I Berlin: Home Fires Burning, (Chapel Hill & London: University of North Carolina Press, 2000), 231.

66.) Richter Lina, Family Life In Germany under The Blockade, (London: National Labour Press Limited, 1919), 51-52.

67.) Belinda Davis, Food Politics, and Everyday Life in World War I Berlin: Home Fires Burning, (Chapel Hill & London: University of North Carolina Press, 2000),193.

68.) Lohr, Eric, A call to Arms: Propaganda, Public Opinion, and Newspapers in the Great War, (WestPort CT: Praeger Publishers, 2004), 91.

69.) Hillgruber, Andreas. The Marshall Cavendish Illustrated Encyclopedia of World War 1 (New York: Marshall Cavendish Corporation, 1984): 182. 2610.

70.) Ibid., p. 2613.

71.) David Englander, The Oxford Illustrated History of the First World War, (oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 198-199.

72.) Vincent, Paul The Politics of Hunger: The Allied Blockade of Germany 1915-1919, (Athens, Ohio London: Ohio University Press, 1985), 124.

73.) Hancock W.K., and Van Der Poel, Jean. Selections from the Smuts Papers: Volume IV November 1918-August 1919, (Cambridge : Cambridge University Press, 2007), 271.