To understand why the blockade was so effective we need to look into how Britain cut German trade from two different angles, first from Britain's own domain, and secondly from neutrals. The former was easier said than done because prior to the First World War, Germany was one of the primary trading partners for British merchants. The English Parliament tried to address this issue headlong early in 1914 with the Trading with the Enemy Act, however as historian John McDermott explains, the laissez-faire style of government was well entrenched in British society and was rigidly protected by both Liberal Party leaders and the business community. He also noted that the economic blockades were traditionally Britain's trump card, but in some instances the government had permitted limited trade if it served British interests. Nonetheless, the Great War was a different kind of conflict and required stricter measures to defeat a world class military power like Germany.

If the aim of the Trading with the Enemy Act was to have the island nation completely cut ties with Germany, then it failed in some respects during the first few years of the conflict. Documentation from the Director of Public Prosecution provides that during the first nine months of the war over ninety cases were tried for continuing commerce with Germany. These cases ranged from minor offenses such as Phillips & Company's attempts to import bicycle handles from Germany - leading to a £500 fine, plus £100.10.6 in fees levied - to more serious violations such as W.D. Dick's attempts to sell coal to Germany contacts which landed him with a sentence of five years imprisonment. Even as late as 1915, after it became obvious that trading with the Central Powers would not be tolerated, British authorities caught and prosecuted an iron firm by the name of Jack & Co. for sending some 7,359 tons of iron ore Germany. While cases such as these would continue throughout the war, McDermott argues that the vast majority of British merchants sacrificed pre-war business networks for the sake of the war effort.

Britain also needed to control neutral states both on the European continent, and others such as United States and many Latin American countries, to completely seal off Germany from foreign imports. In theory these states had no stake in the conflict, but in reality they had much to gain since goods passing through their hands could generate tremendous profit. As the war dragged on each belligerent began to experience shortages in materials such as food, metals, wool and cotton. When these stocks ran out, a country most often needed resupply from foreign markets since no country was entirely self sufficient. So if one side could control all or a majority of these neutral markets, then they could effectively prevent its enemies from obtaining what it needed to continue its war effort.

This was the continued legacy of the era of Liberalism (1846-1914) where an explosion of international trade and growth of national markets took place. International trade increase on average between 4-5 percent each year, leaving much of the world dependent on importation of key supplies to feed its industry and population, and the ability to then export certain commodities for profit or positive trade balance. No longer were nations able to remain in isolation if they wanted to take part in the industrialized world. In short, since the 1850s every major nation throughout the world was now interconnected with many others, and was now dependent on them to keep their factory furnaces burning, agricultural fields yielding, and to create markets for their domestic products to be sold.

British leaders knew from the outset of the war that they could not simply stop all trade throughout the world. What the British could do though was use their position as the world leaders in trade to help swing the majority of neutrals into line with their war plans. First, the British controlled the main seaways that gave northern European neutrals access to the Atlantic. As Marion Siney explains, these were vital to their economy because should merchants be denied the ability to pass the British blockade, or be detained for lengthy inspection of a ship's cargo, then the economy of that nation could crumble quickly. Therefore those neutrals that cooperated with the blockade were assured of speedy inspections, and in many cases, simply waved on to their destination. Intelligence agents stationed at nearly every neutral port would then gather information on whether said ship had indeed gone to its stated port, and to whom those goods had been delivered to. Thus even if a merchant vessel had been spared from detention, it could not simply change its course without risk of being caught and blacklisted.

The United Kingdom also controlled many of the world's most important coal refueling stations. These bases were used by almost every merchant to replenish fuel needed during long voyages. Without access to British resupply points, foreign merchants would find it incredibly difficult, if not impossible to continue its business ventures. Because of this fact, both government and merchant leaders in neutral states began immediate negotiations with British liaisons to ensure they would have access to British controlled resupply points for the future.

Britain also used its position as the world's largest merchant nation to control what important goods went to neutrals during the war. Through centuries of creating the world's largest navy, merchant fleet and overseas colonial empire, Britain was able to command many of the most important raw materials needed for every nation to keep its economy producing finished goods. As Siney explained, they could monitor materials requested by neutrals based on pre-war consumption statistics. When they did so, they watched carefully for large spikes in requests for indexed materials that were known to be needed by Germany. Should a neutral begin to request too much of any specific material, then Britain simply sent only what had been exchanged during the pre-war years, thus eliminating the chances that this commodity would reach Germany.

A second example of how Britain used its control of vital supplies to regulate neutral trade was demonstrated with their control over world jute supplies - vegetable fibers sewn together to make articles such as burlap sacks. Two of the worlds largest jute producing regions - Calcutta, India, and Dundee, Scotland, were both under the direct control of Britain. With this seemingly insignificant product, Britain was able to cripple a Central American coffee company because it refused to cut ties with its Germany contacts. After negotiations with the company were unsuccessful, all shipments of jute to the target firm were halted. Without a continuous supply of jute bags, exporting its coffee beens became nearly impossible.

There was one final way Britain was able to control neutral stocks - they simply bought all or a greater majority of countries surpluses. As Strachan explained, when Britain had reason to believe a neutral was selling its goods to Germany, or noted a large spike in production of a specific good, they bought that commodity in large proportions and paid higher than market value to keep it from reaching German hands. One example of this came in 1917 as the food crisis in Germany was reaching its peak. According to a memorandum presented to the Royal War Cabinet in January 1, 1917, to keep Norwegian fish from entering German markets, the British simply bought all but fifteen percent of the total national catch from that year, which ensured that Norway would have to starve its own people in order to fulfill any German orders.

Finally it should not be assumed that all neutrals cut ties with Germany and joined hands with British. According to the same memorandum, Germany was still obtaining sources of iron ore and food stuff from Swedish contacts. Sweden was able to largely evade British manipulation because many of its exports to Germany were produced exclusively within its borders. For example iron ore was extracted from Swedish mines, not imported from other foreign markets. Sweden was also in a rare position because unlike most other neutrals, Sweden imported few important goods from Britain, but exported several crucial resources to the United Kingdom. Among these significant exports were iron ore and ball bearings, both necessary for Britain to manufacture war goods. Because of these facts, Britain could not risk pushing Sweden too far out of fear that it would lose access to Swedish imports; therefore many crucial supplies continued to reach German markets until the end of the war.Continued on Next Page »

"Battle and Conflict; The Schlieffen plan" Anglia-campus, http://www.jeron.je/anglia/learn/sec/history/ww1/page07.htm

Becker, Jean-Jacques, The Great War and the French People. Providence & Oxford: Berg, 1985.

Belinda Davis, Food Politics, and Everyday Life in World War I Berlin: Home Fires Burning. Chapel Hill & London: University of North Carolina Press, 2000.

Blum, Matthias. "Government Decisions Before and During the First World war and the Living Standards in Germany During a Drastic Natural Experiment" In Exploration in Economic History. 48-4. 2011.

Churchill, Winston. The World Crisis. New York: Free Press, 1931.

Munro, Dana, Sellery, George and Krey, August, German Treatment of Conquered Territory. Washington: The Committee on Public Information, 1918.

Englander, David The Oxford Illustrated History of the First World War. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Phillips, Ethel "American Participation in Belligerent Commercial Controls 1914-1917," In American Society of International Law, 27-4. 1933.

Ferguson, Niall, The Pity of War. Great Britain: The Penguin Group, 1998.

Fritzsche, Peter, Germans into Nazis. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998.

Schreiner, George The Iron Ration Three Years in Warring Central Europe, New York & London: Harper & Brothers Publishing, 1918.

Hancock W.K., and Van Der Poel Jean, Selections from the Smuts Papers: Volume IV November 1918-August 1919. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Hennig, Benjamin. "Applications of hyperspectral remote sensing in coastal ecosystems: A case study from the German North Sea." http://www.hennig-online.net/benjamin/

Hillgruber, Andreas. The Marshall Cavendish Illustrated Encyclopedia of World War 1. New York: Marshall Cavendish Corporation, 1984.

History of World War I. Tarrytown: Marshall Cavendish Corporation, 2002.

Kemp, Peter, The Marshall Cavendish Illustrated Encyclopedia of World War 1. New York: Marshall Cavendish Corporation, 1984.

Kennedy, Greg. "Intelligence and the Blockade, 1914-1917: A Study in Administration, Friction and Command." In Intelligence and National security. No. 5. October 2007.

Kunkel B.W., "Calories and Vitamines," The Scientific Monthly, 17-4. 1923.

Lohr, Eric, A call to Arms: Propaganda, Public Opinion, and Newspapers in the Great War, WestPort: Praeger Publishers, 2004.

McDermott, John. "Trading With the Enemy: British Business and the Law During the First World War." In Canadian Journal of History/Annales canadiennes d'histoire XXXII, August, 1997.

"Memorandum to the War Cabinet on Trade Blockade." United Kingdom National Archives, Note 2. 1917. http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/firstworldwar/spotlights/blockade.htm

Miles Bouton, And The Kaiser Abdicates. New haven: Yale University Press, 1920.

Molodowsky, N "German Foreign Trade Terms in 1899-1913." In The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 41-4. August, 1927.

Murray Rothbard, Herbert Hoover - The Great War and Its Aftermath. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1979.

O'Brien, Patrick. "The Economic Effects of The Great War." In History Today. No. 12. December, 1994.

Offer, Avner. The First World War: An Agrarian Interpretation. New York & Oxford: Clarendon Press; Oxford University Press, 1989.

Osborne, Eric. Britain's Economic Blockade of Germany 1914-1919. London & New York: Frank Cass, 2004.

Richter Lina, Family Life In Germany under The Blockade. London: National Labour Press Limited, 1919.

Shaw, Bernard. Family Life in Germany Under the Blockade. National Labour Press Limited: London, 1919.

Siney, Marion. The allied blockade of Germany 1914-1916. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1957.

Strachan, Hew. The First World War. New York: Penguin Books, 2005.

Tomes Jason, Balfour and foreign policy - The International Thoughts of a Conservative Statesman. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Tuchman, Barbara, The Guns of August. New York: Macmillan, 1962.

Van Der Kloot, William. "Ernst Starling's Analysis of the Energy Balance of the German People During the Blockade 1914-1919." In Notes and records of the Royal Society of London. 57-2. May, 2003.

Vincent, Paul The Politics of Hunger: The Allied Blockade of Germany 1915-1919. Athens, Ohio London: Ohio University Press, 1985.

Virneth Studios Ltd, "The Battle of Jutland 31st May 1916 - Background." 3D History, http://www.3dhistory.co.uk/ww1/naval-warfare/jutland-backgound.php.

Zweiniger-Bargielowska Ina, Duffett Rachel, and Drouard Alain, Food and War in Twentieth Century Europe. Burlington: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2001.

Appendix

Appendix A

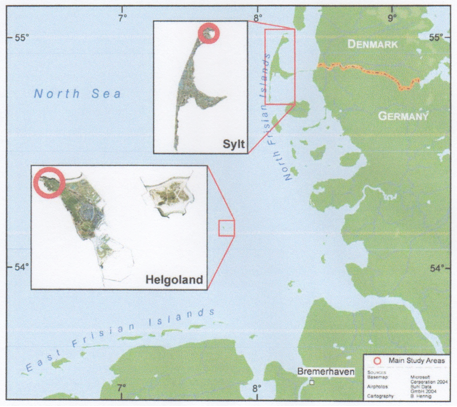

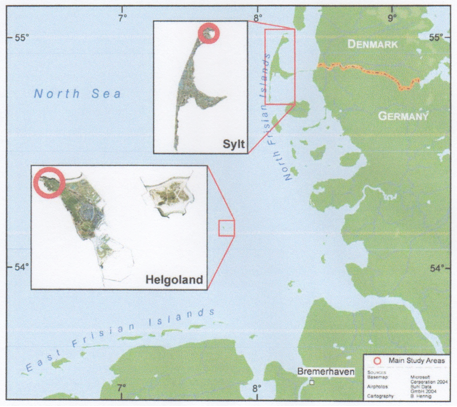

Figure 1. Location of German islands Heligoland and Sylt

Source: Hennig, Benjamin. hennig-online.net, "Applications of hyperspectral remote sensing in coastal ecosystems: A case study from the German North Sea ." Last modified 2007. Accessed October 1, 2013. http://www.hennig-online.net/benjamin/.

Appendix B

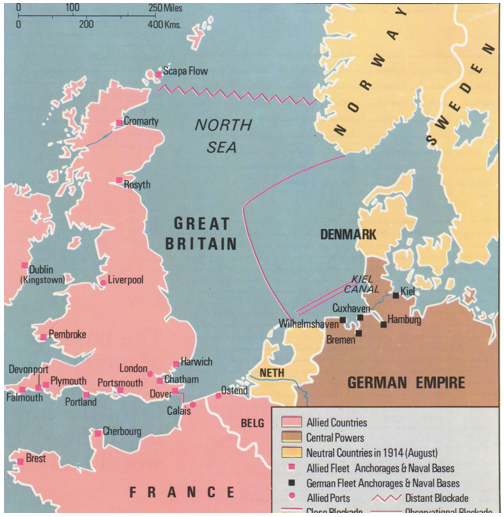

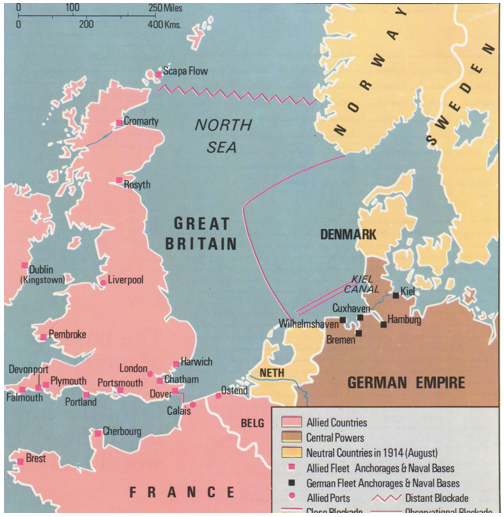

Figure 2. Location of Royal Navy 'observational blockade' plan 1912.

Source: The Marshall Cavendish Illustrated Encyclopedia of World War 1 (New York: Marshall Cavendish Corporation, 1984): 177.

Appendix C

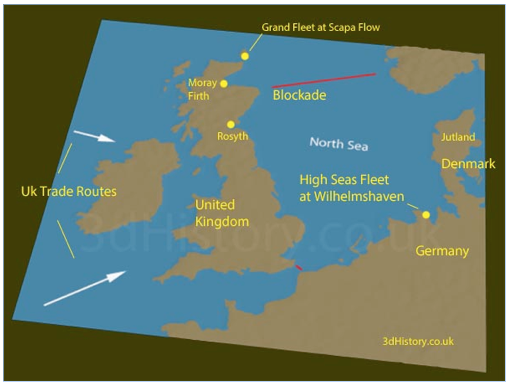

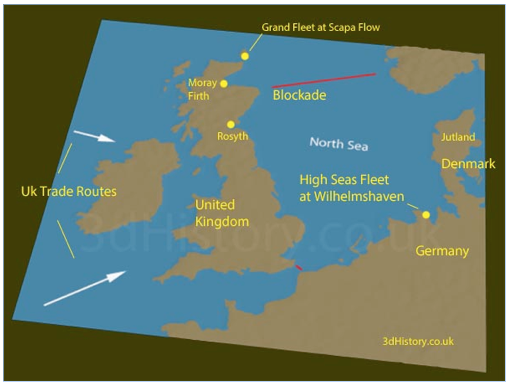

Figure 3. Site of Royal Navy 'distant blockade' plan established 1914-1919

Source: Virneth Studios Ltd "The Battle of Jutland 31st May 1916 - Background." Accessed September 30, 2013. http://www.3dhistory.co.uk/ww1/naval-warfare/jutland-backgound.php.

Appendix D

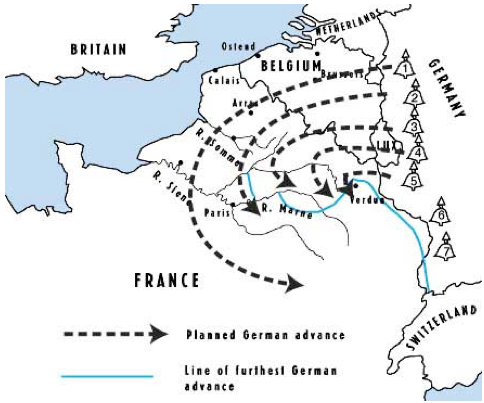

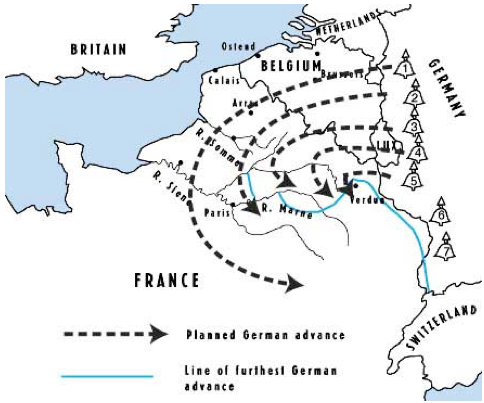

Figure 4. Schlieffen plan as executed on the western front in August 1918.

Source: "Battle and Conflict; The Schlieffen plan" Accessed October 13, 2013. http://www.jeron.je/anglia/learn/sec/history/ww1/page07.htm

Appendix E

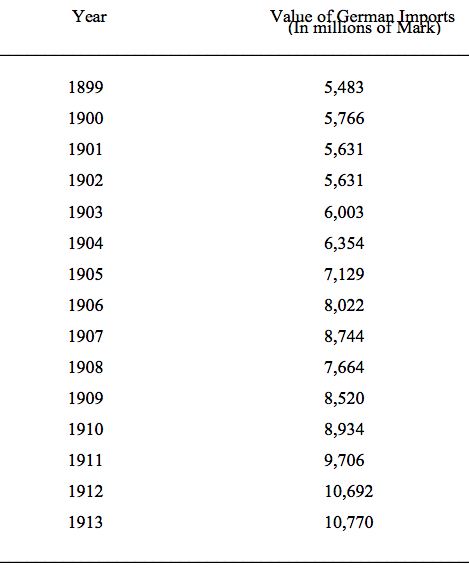

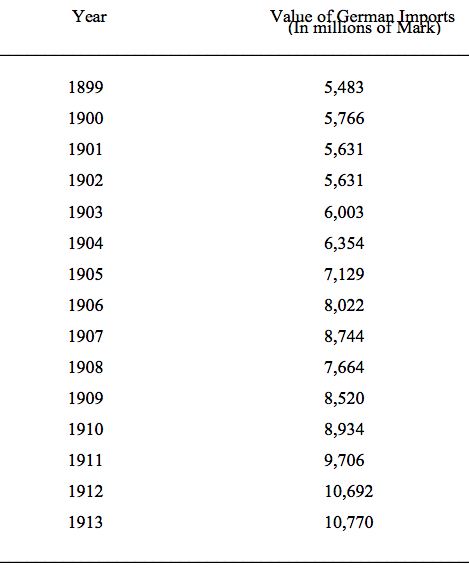

Table 2.1. German import statistics from 1899-1913

Source: Molodowsky N. "German Foreign Trade Terms 1899-1913" The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 41, no. 4 (Aug 1927): 666.

Appendix F

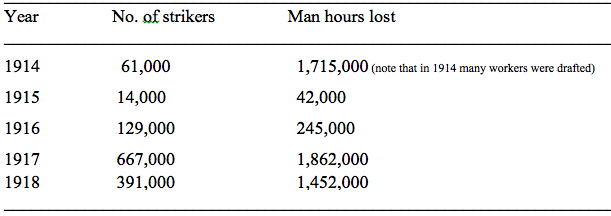

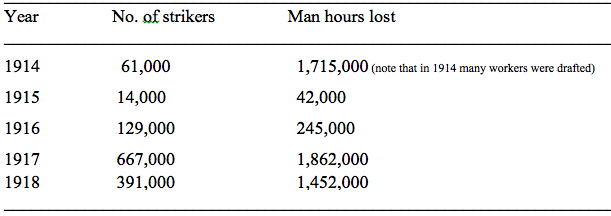

Table 2.2. Strikes in Germany 1914-1918

Source: Ferguson, Niall, The Pity of War (Great Britain: The Penguin Group, 1998): 275

Appendix H

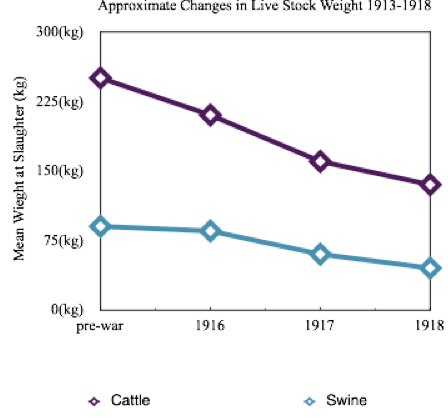

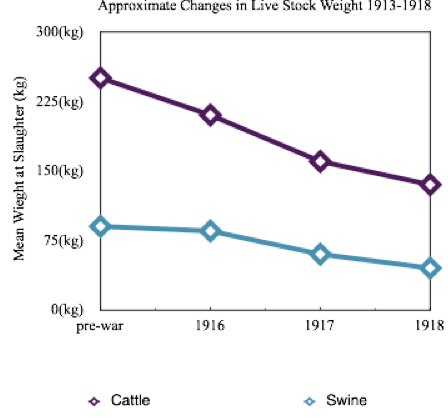

Figure 6 Weights of German Farm animals when slaughtered 1913-1918.

Source: Van Der Kloot, William. Ernst Starling's Analysis of the Energy Balance of the German People During the Blockade 1914-1919." Notes and records of the Royal Society of London. Vol. 57, No. 2 (May 2003): 189.

Appendix I

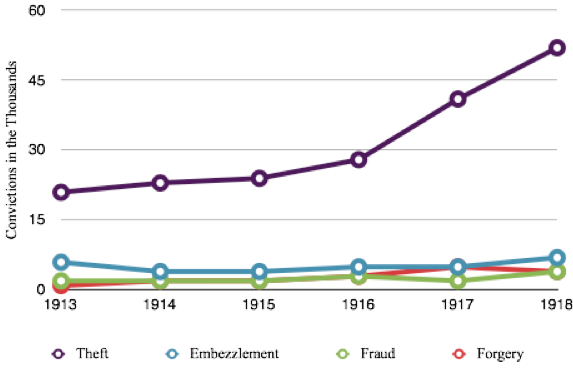

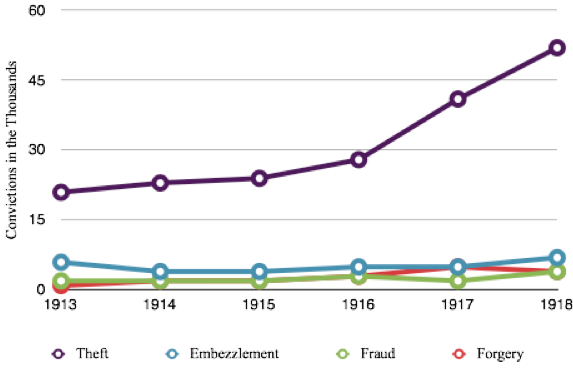

Table 1.3 Women convicted of crimes 1913-1918

Source: Belinda Davis, Food Politics, and Everyday Life in World War I Berlin: Home Fires Burning, (Chapel Hill & London: University of North Carolina Press, 2000), 223.

Endnotes

1.) Osborne, Eric. Britain's Economic Blockade of Germany 1914-1919, (London & New York: Frank Cass, 2004), 1.

2.) Kennedy, Greg. "Intelligence and the Blockade, 1914-1917: A Study in Administration, Friction and Command." Intelligence and National security. no. 5 (Oct. 2007): 700.

3.) Tomes Jason, Balfour and foreign policy - The International Thoughts of a Conservative Statesman, (Cambridge : Cambridge University Press, 1997), 133-134.

4.) Kemp, Peter, The Marshall Cavendish Illustrated Encyclopedia of World War 1, (New York: Marshall Cavendish Corporation, 1984): 182.

5.) Kemp Peter, The Marshall Cavendish Illustrated Encyclopedia of World War 1, (New York: Marshall Cavendish Corporation, 1984): 182.

6.) Ibid., p. 182.

7.) Kennedy, Greg. "Intelligence and the Blockade, 1914-1917: A Study in Administration, Friction and Command." Intelligence and National security. no. 5 (Oct. 2207): 701.

8.) Ibid., p. 710.

9.) Ibid., p. 716.

10.) Siney, Marion. The allied blockade of Germany 1914-1916. The University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor. (1957): 24.

11.) McDermott, John. "Trading With the Enemy: British Business and the Law During the First World War." Canadian Journal of History/Annales canadiennes d'histoire XXXII. (Aug 1997): 202-203.

12.) Ibid., p. 209.

13.) Ibid., p. 210.

14.) O'Brien, Patrick. "The Economic Effects of The Great War." History Today. no. 12 (Dec. 1994): 22.

15.) Siney, Marion. The allied blockade of Germany 1914-1916. The University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor. (1957): 34.

16.) Ethel Phillips, "American Participation in Belligerent Commercial Controls 1914-1917," American Society of International Law, 27, no. 4 (1933): 684.

17.) Kennedy, Greg. "Intelligence and the Blockade, 1914-1917: A Study in Administration, Friction and Command." Intelligence and National security. no. 5 (Oct. 2207): 709-710.

18.) Ibid., p. 686.

19.) Strachan, Hew. The First World War. New York: Penguin Books. (2005) 217.

20.) United Kingdom National Archives, "Memorandum to the War Cabinet on Trade Blockade ." Note 2. Accessed September 15, 2013. http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/firstworldwar/spotlights/blockade.htm.

21.) Ibid., Note 2.

22.) Ibid., Note 3.

23.) Molodowsky, N "German Foreign Trade Terms in 1899-1913," The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 41, no. 4 (Aug 1927): 666.

24.) Ibid., p. 688.

25.) Van Der Kloot, William. "Ernst Starling's Analysis of the Energy Balance of the German People During the Blockade 1914-1919." Notes and records of the Royal Society of London. Vol. 57, No. 2 (May 2003): 187.

26.) Paul Vincent, The Politics of Hunger: The Allied Blockade of Germany 1915-1919, (Athens, Ohio London: Ohio University Press, 1985), 5.

27.) Tuchman, Barbara, The Guns of August, (New York: Macmillan, 1962), 20.

28.) Ibid., p. 21.

29.) Ibid., p 128-129.

30.) Kunkel, B.W. "Calories and Vitamines," The Scientific Monthly, 17, no. 4 (1923): 364,

31.) Van Der Kloot, William. "Ernst Starling's Analysis of the Energy Balance of the German People During the Blockade 1914-1919." Notes and records of the Royal Society of London. Vol. 57, No. 2 (May 2003): 189.

32.) Richter Lina, Family Life In Germany under The Blockade, (London: National Labour Press Limited, 1919), 21.

33.) Vincent, Paul The Politics of Hunger: The Allied Blockade of Germany 1915-1919, (Athens, Ohio London: Ohio University Press, 1985), 21.

34.) George Schreiner, The Iron Ration Three Years in Warring Central Europe, (New York and London: Harper & Brothers Publishing, 1918), 174.

35.) N/A, History of World War I, (Tarrytown: Marshall Cavendish Corporation, 2002), 658.

36.) Ibid., p. 665.

37.) Strachan, Hew. The First World War. New York: Penguin Books. (2005) 218.

38.) Ibid., p. 218.

39.) Ibid., p. 218.

40.) Churchill, Winston The World Crisis, (New York: Free Press, 1931), 686.

41.) Siney, Marion. The allied blockade of Germany 1914-1916. The University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor. (1957): 47.

42.) United Kingdom National Archives, "Memorandum to the War Cabinet on Trade Blockade ." Note 1. Accessed September 15, 2013. http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/firstworldwar/spotlights/blockade.htm.

43.) Strachan, Hew. The First World War. New York: Penguin Books. (2005) 215.

44.) Van Der Kloot, William. "Ernst Starling's Analysis of the Energy Balance of the German People During the Blockade 1914-1919." Notes and records of the Royal Society of London. Vol. 57, No. 2 (May 2003): 189-190.

45.) Vincent, Paul The Politics of Hunger: The Allied Blockade of Germany 1915-1919, (Athens, Ohio London: Ohio University Press, 1985), 138.

46.) Richter Lina, Family Life In Germany under The Blockade, (London: National Labour Press Limited, 1919), 32.

47.) Vincent, Paul, The Politics of Hunger: The Allied Blockade of Germany 1915-1919, (Athens, Ohio London: Ohio University Press, 1985), 137.

48.) Ibid., p. 128.

49.) Richter Lina, Family Life In Germany under The Blockade, (London: National Labour Press Limited, 1919), 22.

50.) Vincent, Paul The Politics of Hunger: The Allied Blockade of Germany 1915-1919, (Athens, Ohio London: Ohio University Press, 1985), 128.

51.) Miles Bouton, And The Kaiser Abdicates, (New haven: Yale University Press, 1920), 73.

52.) Richter Lina, Family Life In Germany under The Blockade, (London: National Labour Press Limited, 1919), 29.

53.) Ibid., p. 45.

54.) Ibid., p. 45-46.

55.) Zweiniger-Bargielowska Ina, Duffett Rachel, and Drouard Alain, Food and War in Twentieth Century Europe, (Burlington: Ashgate Publishing Limited , 2001), 15.

56.) Van Der Kloot, William. "Ernst Starling's Analysis of the Energy Balance of the German People During the Blockade 1914-1919." Notes and records of the Royal Society of London. Vol. 57, No. 2 (May 2003): 190.

57.) Miles Bouton, And The Kaiser Abdicates, (New haven: Yale University Press, 1920), 73.

58.) Dana Munro, George Sellery, and August Krey, German Treatment of Conquered Territory , (Washington : The Committee on Public Information , 1918).16-17.

59.) Vincent, Paul The Politics of Hunger: The Allied Blockade of Germany 1915-1919, (Athens, Ohio London: Ohio University Press, 1985), 131.

60.) Belinda Davis, Food Politics, and Everyday Life in World War I Berlin: Home Fires Burning, (Chapel Hill & London: University of North Carolina Press, 2000), 201.

61.) Murray Rothbard, Herbert Hoover - The Great War and Its Aftermath, (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1979), 93.

62.) Belinda Davis, Food Politics, and Everyday Life in World War I Berlin: Home Fires Burning, (Chapel Hill & London: University of North Carolina Press, 2000), 210-211.

63.) Ibid., p. 210

64.) Fritzsche Peter, Germans into Nazis, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998), 31.

65.) Belinda Davis, Food Politics, and Everyday Life in World War I Berlin: Home Fires Burning, (Chapel Hill & London: University of North Carolina Press, 2000), 231.

66.) Richter Lina, Family Life In Germany under The Blockade, (London: National Labour Press Limited, 1919), 51-52.

67.) Belinda Davis, Food Politics, and Everyday Life in World War I Berlin: Home Fires Burning, (Chapel Hill & London: University of North Carolina Press, 2000),193.

68.) Lohr, Eric, A call to Arms: Propaganda, Public Opinion, and Newspapers in the Great War, (WestPort CT: Praeger Publishers, 2004), 91.

69.) Hillgruber, Andreas. The Marshall Cavendish Illustrated Encyclopedia of World War 1 (New York: Marshall Cavendish Corporation, 1984): 182. 2610.

70.) Ibid., p. 2613.

71.) David Englander, The Oxford Illustrated History of the First World War, (oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 198-199.

72.) Vincent, Paul The Politics of Hunger: The Allied Blockade of Germany 1915-1919, (Athens, Ohio London: Ohio University Press, 1985), 124.

73.) Hancock W.K., and Van Der Poel, Jean. Selections from the Smuts Papers: Volume IV November 1918-August 1919, (Cambridge : Cambridge University Press, 2007), 271.