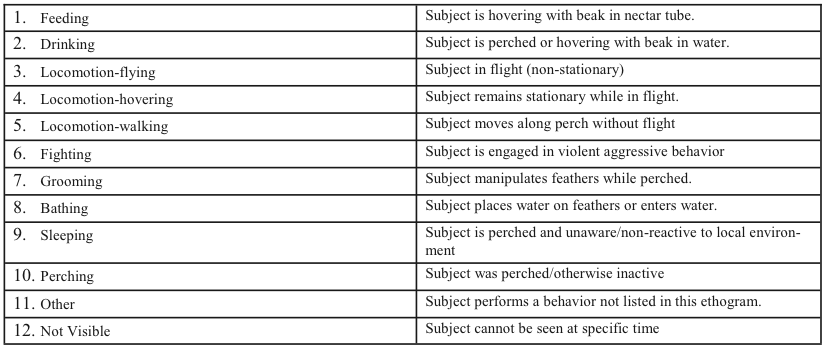

From Discussions VOL. 5 NO. 1Adaptations and Preferences of Wild Hummingbirds Introduced into a Captive SettingDISCUSSIONThe location for both subjects was very specific. As illustrated in Figures 1 and 2, both subjects were prone to certain locations. Both subjects preferred to be in the back row, farthest away from public viewing and the keeper maintenance areas. This appears to demonstrate that both subjects prefer to be as far away from humans as possible. A. prevostii initially preferred to be at the highest point of the exhibit (quadrant 11), and then moved to a lower position (quadrant 10). A. prevostii's initial prevalent location could demonstrate an initial stress to the environment, the public (Demarset, Durrant, & Gibbons 1995), or other birds in the exhibit. Such a response could explain the high vantage point. Gradual acclamation to the environment could be a possible explanation for its change in preferential location. The behavior of A. prevostii in the exhibit is comparable to its known behavior in the wild. High and open locations are known favorites of this species as they allow the bird to be vigilant and watch for potential predators. C. coruscans demonstrated a clear preference for quadrant 17. This quadrant is in the right, middle of the back row and is mostly covered by plants and trees. The location where C. coruscans was most often observed was on a small branch within a tree. This sheltered location as well as the heightened aggression noted in Figure 4 could be indicative of its territorial nature. Such a behavior is similar to its known natural behavior. Hummingbirds are known to be territorial, especially in regards to feeding locations (Carpenter, Hixon, Paton 1983). The social proximities observed for both birds were that they were isolated from the other birds; however, they were still very observant of the birds around them. This also follows what is known about hummingbird behavior. Hummingbirds, in general, are known to be solitary when not breeding. The behavior of both birds in isolation was relatively identical to the behavior they exhibited in the Free Flight Aviary. This similarity is most likely due to the fact that the temporary holding cages were not conducive to extensive movement of the hummingbirds. Such extensive movement may have been prevented due to cage obstructions. In Free Flight, both birds were most often observed in a perched position. While both birds did fly for short periods of time, these rarely overlapped with observation times, reflected in Figure 6. This behavior is prevalent in hummingbirds since their rapid metabolism requires them to rest often. However perching for such long periods of time is probably uncommon. As a result, long periods of flight are probably uncommon. Hummingbirds are especially flighty and much more prone to flight as it is their only means of escape, especially as their feet are ill-equipped to walk even short distances. This reoccurring behavior is most likely caused by captivity and prolonged exposure/close proximity to so many other birds. As both birds were confined to the same space as other birds, it appears that their behaviors tended to become more observant than evasive. This experiment placed focus on the after affects of placing both subjects into a large aviary setting, Free Flight, in order to see the effects. This experiment was limited since it did not take into account several factors that could be the basis for future studies. These factors include the effects of people (public and keepers), the amount and distribution of light, concentration of nectar, as well as many others. These factors would provide even more information about these species. In conclusion, the data shows a clear preference within the Free Flight exhibit. Both subjects demonstrated clear preferences in both location and behavior. The location varied for each hummingbird; however this agreed with the territorial nature of the type of bird. Perching was the predominant behavior for both birds. This behavior was probably a result of both natural instincts and adjusting to a captive environment. While both subjects were originally from the wild, both demonstrated some acclimation to their new environment, whether it was in location (for A. prevostii) or behavior (for both subjects). AcknowledgementsI would like to thank Dr. Kristen Lukas for her help throughout the duration of my research. I would also like to that the staff in the Bird Department at the Brookfield zoo. I would essecially like to thank my mentor at the zoo, Mr. Lee Stahl, who was always there to guide me, and help me in whatever way needed. I would also like to thank Megan Ross and Elena A. Hoellein for their ideas and support. ReferencesAlderfer, Jonathon. National Geographic Complete Birds of North America. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic, 2005. Campbell, Bruce. The Dictionary of Birds in Color. London: The Viking Press Inc, 1974. Carpenter, F L., Mark A. Hixon, and David C. Paton. Weight Gain and Adjustment of Feeding Territory Size in Migrant Hummingbirds. Vol. 80. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences, 1983. Demarset, Jack, Barbara S. Durrant, and Edwards F. Gibbons. Conservation of Endangered Species in Captivity: An Interdisciplinary Approach. New York: State University of New York Press, 1995. Perrins, Christopher. Firefly Encyclopedia of Birds. Vol. 4. Buffalo, N.Y.: Firefly Books LTP, 2003. ADDENDUM I: ETHOGRAM OF OBSERVED BEHAVIORS

Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in Biology |