To begin with, the television programs The Good Wife, Law & Order: SVU, Fairly Legal and Major Crimes were selected to study. They were chosen because of their consistently large audiences and high ratings.23 The fourth and seventh episodes of each television program’s season broadcast within a one-year period were watched. Often times, the premier and finale episodes of a television program are more sensationalized or dramatic, so by selecting the fourth and seventh episodes within a program’s season, this research avoided those extremes. The one-year period spanned from September 2011 to September 2012.

Through content analysis, each episode was analyzed and coded through its presentation of three themes: suspects’ treatment, the case building process and trial length.

In terms of suspects’ treatment, episodes were watched to determine whether the characters representing police officers, detectives or interviewers referred to the pre-trial interactions with suspects as interviews or interrogations. Historically, interviews produce voluntary statements while interrogations coerce confessions.

24 Further, it was noted whether or not police officers, detectives or interviewers physically harassed suspects while questioning them. Physical harassment can include such things as performing “threatening or intimidating actions, blocking a person’s path with intent to intimidate or threaten, pushing, shoving or purposely bumping into a person and performing unwelcome touching, caressing or fondling.”

25 Finally, it was noted whether or not police officers, detectives or interviewers presumed innocent suspects were guilty. According to Saul M. Kassin et al:

That interrogation is by definition a guilt-presumptive process, a theory-driven social interaction led by an authority figure who already believes that he or she is interrogating the perpetrator and for whom a just outcome is measured by confession. In the case of innocent suspects, one would hope that investigators would periodically reevaluate their beliefs. Over the years, however, a good deal of research has shown that once people form an impression, they unwittingly seek, interpret and create behavioural data that verify it. This last phenomenon – often referred to as the behavioral conformation bias – has been observed not only in the laboratory but in classrooms, the military, the workplace and other settings.26

In terms of the case building process, each episode was watched to determine what type of attorney was building the case. Additionally, each episode was watched to determine how long it took an attorney to build his or her case. For a frame of reference, Casey Anthony’s attorney, Jose Boaz, spent approximately three years preparing his defense case for Anthony’s murder trial.27

When considering the portrayal of trial length, it was noted whether or not the preliminary hearing, the arraignment, the discovery and motion practices, the plea bargain, the entry of plea and the trial were mentioned in the episodes. If a trial did occur, the episode was watched to determine how long the trial lasted, if a jury was present and if the defendant’s sentencing was addressed. Though a particular trial may be longer or shorter than the average, a criminal trial typically lasts between five and ten days.28

Episodes could be classified in one of two categories:

- Accurate: The episode portrayed the treatment of suspects, the case building process and trial length accurately based on real-world legal facts.

- Inaccurate: The episode exaggerated or inaccurately portrayed the treatment of suspects, the case building process and trial length in comparison to real-world legal facts.

Framing themes in the episodes will be noted. If accurate portrayals of suspects’ treatment, the case building process and trial length are illustrated, the episode falls under a normal framing context. If any inaccuracies or exaggerations are presented, that frame is recorded.

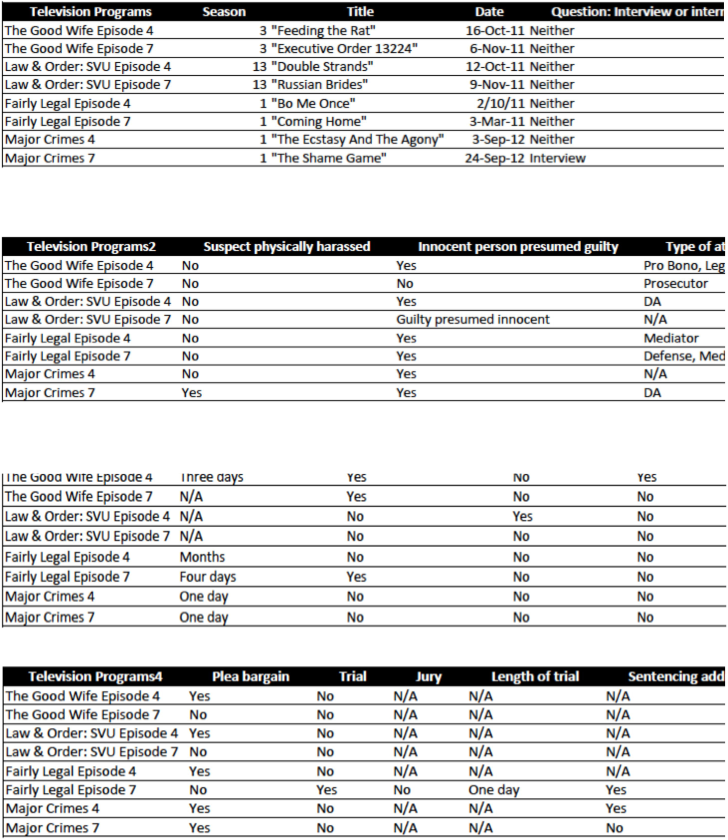

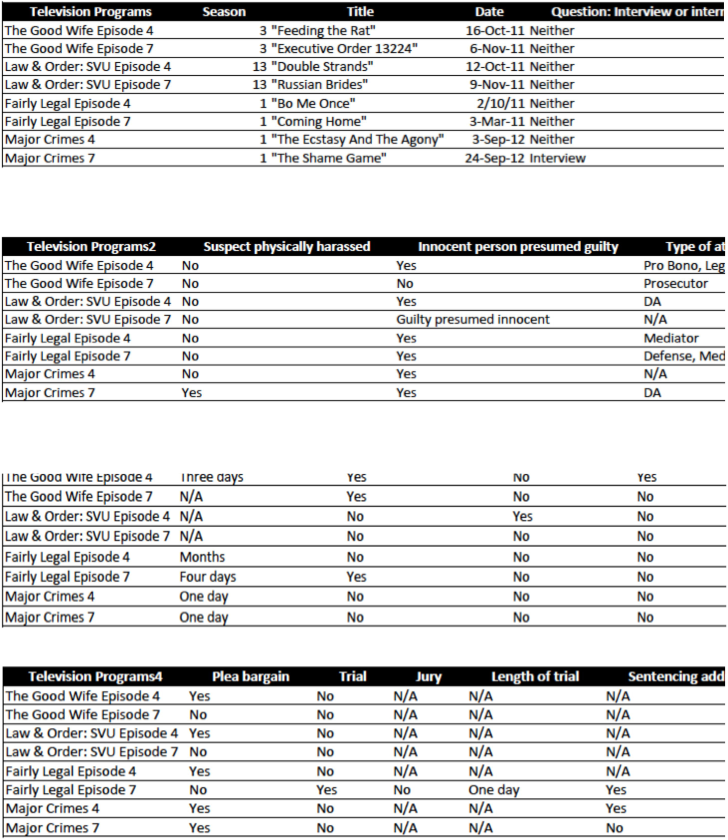

Eight episodes were coded in this study. Each episode aired during a one-year period spanning from September 2011 to September 2012. The episodes studied include The Good Wife’s “Feeding the Rat” and “Executive Order 13224,” Law & Order: SVU’s “Double Strands” and “Russian Brides,” Fairly Legal’s “Bo Me Once” and “Coming Home” and Major Crimes’ “The Ecstasy and the Agony” and “The Shame Game.”

In terms of suspects’ treatment, only one episode, “The Shame Game,” referred to pre-trial interactions with suspects as interviews. All others did not reference the interaction as an interview or an interrogation. “The Shame Game” was also the only episode to show police detectives physically harassing a suspect in the questioning room. However, six of the eight episodes showed instances where innocent suspects were presumed guilty. For example, in the Law and Order: SVU episode “Double Strands,” suspect Gabriel Thomas is wrongly accused of being a serial rapist, and because of this false accusation, he attempts to commit suicide while awaiting his trial in prison. However, his identical twin, Brian Smith, is found to be the actual serial rapist at the end of the episode.

In terms of the case building process, two episodes assigned district attorneys to build the legal cases, while two had mediators, one a prosecutor and one a pro bono lawyer. The remaining two episodes did not specify what types of lawyers were building the cases.

Five of the eight episodes specified how long it took the attorney to build his or her case. In two episodes, the attorneys built their cases in one day. In one episode, a lawyer built her case in four days. It took an attorney three days to build her case in one episode, and in another, it took her months.

When considering the portrayal of trial length, only three of the eight episodes mentioned the preliminary hearing. One mentioned arraignment, one mentioned the discovery and motion practices, and five mentioned the plea bargain. Only one episode, “Coming Home,” included a trial, but the trial only lasted one day, and there was no jury present in the courtroom. Three episodes mentioned the convicted criminals’ sentencing, though two of those three did not show a trial or its preliminary processes. (For a full reference of the coding, see Appendix.)Continued on Next Page »

“Casey Anthony Trial: Timeline of Key Events in the Murder Trial of the Florida Mother,” ABC News, July 6, 2012, http://abcnews.go.com/US/casey-anthony-trial-timeline-key-events/ story?id=13990853&page=3#.UKhS94VrZr0 (Retrieved on November 17, 2012).

“CBS Primetime TV Schedule,” CBS, n.d., http://www.cbs.com/schedule/ (September 17, 2012).

Cressey, Donald R. “Criminological Research and the Definition of Crimes,” American Journal of Sociology 56 (1951): 547.

“Crime Most Common Story on Local Television News,” Kaiser Family Foundation, March 12, 1998, http://www.kff.org/mediapartnerships/1374-crime.cfm (September 17, 2012).

Graybow, Martha. “Prosecutors See ‘CSI Effect in White-Collar Cases,” Reuters, September 24, 2005, http://www.redorbit.com/news/general/250029/prosecutors_see_csi_effect_in_whitecollar_cases/ (October 23, 2012).

Kassin, Saul M., et al. “Interviewing suspects: Practice, science, and future directions,” Legal and Criminology Psychology 15 (2010): 39-41.

King, Nancy Jean. “The American Criminal Jury,” Law and Contemporary Problems, 62 (1999): 41, 59. Lawson, Tamara F. “Before the Verdict and Beyond the Verdict: The CSI Infection Within Modern Criminal Jury Trials,” Loyola University Chicago Law Journal 41 (2009): 121. Legal Information Institute, s.v. “Legal Systems.”

“Physical Harassment,” SC Budget and Control Board, n.d., http://ohrweb.ohr.state.sc.us/OHR/antiharassment/Page15.htm (November 17, 2012).

Roane, Kit R. “The CSI Effect,” U.S. News & World Report, April 17, 2005, Tech section, 1-2. “Schedule,” NBC, n.d., http://www.nbc.com/schedule/ (September 17, 2012).

“Schedule,” TNT, n.d., http://www.tntdrama.com/schedule/?startDate=10/1/2012&timeZone= (September 30, 2012).

“Schedule,” USA, n.d., http://www.usanetwork.com/series/fairlylegal/theshow/episodeguide/episodes/s2_rippleofhope/index.html (September 30, 2012).

Stelter, Brian. “Casey Anthony Verdict Brings HLN Record Ratings,” New York Times, July 6, 2011, http://mediadecoder.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/07/06/casey-anthony-verdict-brings-hln-record-ratings/ (September 17, 2012).

“Top 20 Network Primetime Series: Oct. 8-14, 2012,” Nielsen Television (TV) Ratings for Network Primetime Series, n.d., http://www.zap2it.com/tv/ratings/zap-weekly-ratings,0,7508066.htmlstory (October 23, 2012).

“Top Tens & Trends of Television,” Nielsen, August 20, 2012, http://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/top10s/television.html (September 30, 2012).

“Trial Juror’s Handbook,” New York State Unified Court System, n.d., www.nyjuror.gov (October 23, 2010). Tyler, Tom R. “Viewing CSI and the Threshold of Guilt: Managing Truth and Justice in Reality and Fiction,” The Yale Law Journal 115 (2006): 1052.

“Violent Crime,” Federal Bureau Investigation, n.d., http://www.fbi.gov/about-us/cjis/ucr/crime-in-the-u.s/2010/crime-in-the-u.s.-2010/violent-crime/violent-crime (September 17, 2012).

“What are some common steps of a criminal investigation and prosecution?” National Crime Victim Law Institute, 2012, http://law.lclark.edu/live/news/5498-what-are-some-common-steps-of-a-criminal/law/ centers/national_crime_victim_law_institute/for_victims/answers/ (October 23, 2012).

Willing, Richard. “‘CSI effect’ has juries wanting more evidence,” USA Today, August 5, 2004, News section, http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/nation/2004-08-05-csi-effect_x.htm (October 23, 2012).

Young Lawyer’s Section, Bar Association of the District of Columbia, 4th ed., s.v. “Criminal Jury Instructions for the District of Columbia.”

Endnotes

1.) “Violent Crime,” Federal Bureau Investigation, n.d., http://www.fbi.gov/about-us/cjis/ucr/crime-in-the- u.s/2010/crime-in-the-u.s.-2010/violent-crime/violent-crime (September 17, 2012).

2.) “Crime Most Common Story on Local Television News,” Kaiser Family Foundation, March 12, 1998, http://www.kff.org/mediapartnerships/1374-crime.cfm (September 17, 2012).

3.) Brian Stelter, “Casey Anthony Verdict Brings HLN Record Ratings,” New York Times, July 6, 2011, http://mediadecoder.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/07/06/casey-anthony-verdict-brings-hln-record-ratings/ (September 17, 2012).

4.) “CBS Primetime TV Schedule,” CBS, n.d., http://www.cbs.com/schedule/ (September 17, 2012).

5.) “Schedule,” NBC, n.d., http://www.nbc.com/schedule/ (September 17, 2012).

6.) “Schedule,” USA, n.d., http://www.usanetwork.com/series/fairlylegal/theshow/episodeguide/episodes/s2_rip- pleofhope/index.html (September 30, 2012).

7.) “Schedule,” TNT, n.d., http://www.tntdrama.com/schedule/?startDate=10/1/2012&timeZone= (September 30, 2012).

8.) Tamara F. Lawson, “Before the Verdict and Beyond the Verdict: The CSI Infection Within Modern Criminal Jury Trials,” Loyola University Chicago Law Journal 41 (2009): 121.

9.) Black’s Law Dictionary, 2nd ed., s.v. “Crime.”

10.) Legal Information Institute, s.v. “Legal Systems.”

11.) Tamara F. Lawson, “Before the Verdict and Beyond the Verdict,” 128-129.

12.) “Top 20 Network Primetime Series: Oct. 8-14, 2012,” Nielsen Television (TV) Ratings for Network Pri- metime Series, n.d., http://www.zap2it.com/tv/ratings/zap-weekly-ratings,0,7508066.htmlstory (October 23, 2012).

13.) Kit R. Roane, “The CSI Effect,” U.S. News & World Report, April 17, 2005, Tech section, 1-2.

14.) Tom R. Tyler, “Viewing CSI and the Threshold of Guilt: Managing Truth and Justice in Reality and Fiction,” The Yale Law Journal 115 (2006): 1052.

15.) Young Lawyer’s Section, Bar Association of the District of Columbia, 4th ed., s.v. “Criminal Jury Instructions for the District of Columbia.”

16.) Kit R. Roane, “The CSI Effect,” 1-2.

17.) Tamara F. Lawson, “Before the Verdict and Beyond the Verdict,” 132.

18.) Richard Willing, “‘CSI effect’ has juries wanting more evidence,” USA Today, August 5, 2004, News sec- tion, http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/nation/2004-08-05-csi-effect_x.htm (October 23, 2012).

19.) Martha Graybow, “Prosecutors See ‘CSI Effect’ in White-Collar Cases,” Reuters, September 24, 2005, http://www.redorbit.com/news/general/250029/prosecutors_see_csi_effect_in_whitecollar_cases/ (October 23, 2012).

20.) Nancy Jean King, “The American Criminal Jury,” LAW & CONTEMP. PROBS 62 (1999): 41, 59.

21.) Tamara F. Lawson, “Before the Verdict and Beyond the Verdict,” 127.

22.) Tamara F. Lawson, “Before the Verdict and Beyond the Verdict,” 124-125.

23.) “Top Tens & Trends of Television,” Nielsen, August 20, 2012, http://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/top10s/television.html (September 30, 2012).

24.) Saul M. Kassin et al., “Interviewing suspects: Practice, science, and future directions,” Legal and Criminology Psychology 15 (2010): 39.

25.) “Physical Harassment,” SC Budget and Control Board, n.d., http://ohrweb.ohr.state.sc.us/OHR/antiharass- ment/Page15.htm (November 17, 2012).

26.) Saul M. Kassin et al., “Interviewing suspects,” Legal and Criminology Psychology 15 (2010): 41.

27.) “Casey Anthony Trial: Timeline of Key Events in the Murder Trial of the Florida Mother,” ABC News, July 6, 2012, http://abcnews.go.com/US/casey-anthony-trial-timeline-key-events/story?id=13990853&page=3#. UKhS94VrZr0 (November 17, 2012).

28.) “Trial Juror’s Handbook,” New York State Unified Court System, n.d., www.nyjuror.gov (October 23, 2010).

29.) Saul M. Kassin et al., “Interviewing suspects,” Legal and Criminology Psychology 15 (2010): 41.

30.) “What are some common steps of a criminal investigation and prosecution?” National Crime Victim Law Institute, 2012, http://law.lclark.edu/live/news/5498-what-are-some-common-steps-of-a-criminal/law/centers/ national_crime_victim_law_institute/for_victims/answers/ (October 23, 2012).

Appendix: Coding Sheets