From Elon Journal of Undergraduate Research in Communications VOL. 4 NO. 1Pumping Steel and Sex Appeal: Message Strategies and Content in Dietary Supplement Advertisements

IN THIS ARTICLE

KEYWORDS

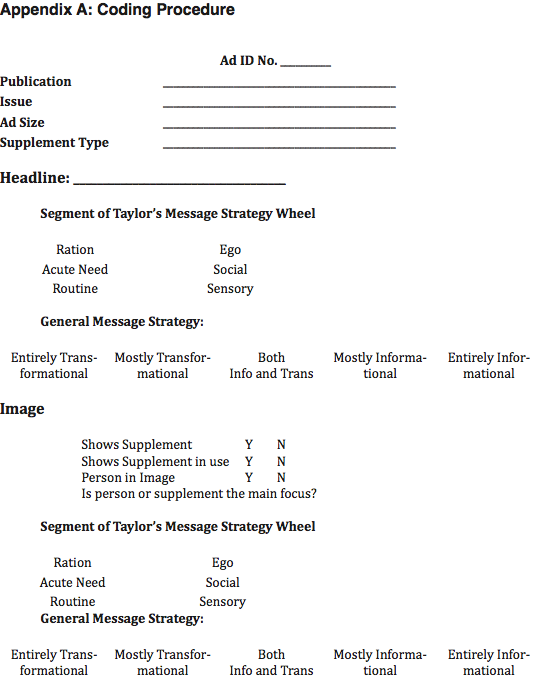

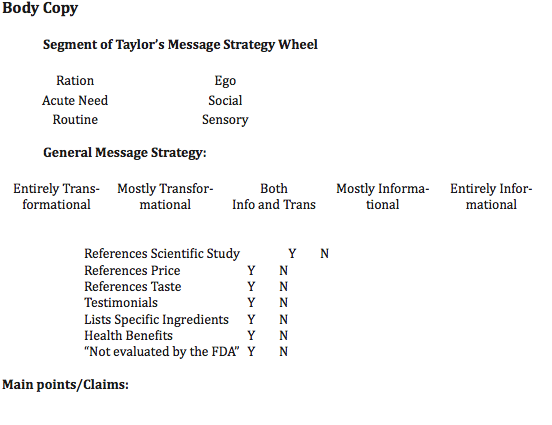

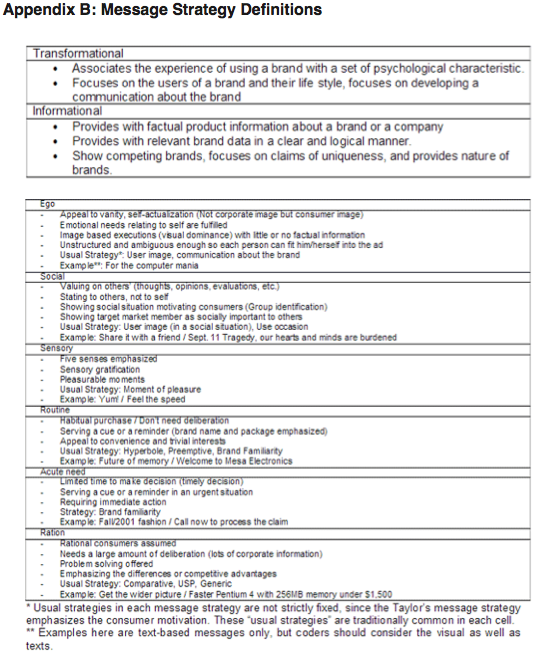

AbstractExisting in a regulatory gray area as neither a food nor a drug, dietary supplements have fierce controversies over safety and regulation. This regulatory state can create a problem if the persuasion of supplement ads convince consumers to purchase harmful products. Using Taylor's Six-Segment Message Strategy Wheel, this study analyzed the relationship between informational print ads for dietary supplements and transformational message strategies. Transformational strategies, appeals to viewer's emotions or sense of self, were used more frequently in ads than their Informational counterparts, revealing that supplement manufacturers may be selling their products based on a better body image than actual health benefits. A lack of information about supplement ingredients and effects in ads also revealed an imbalance between information and persuasion. I. IntroductionPressure to conform to increasingly unrealistic societal definitions of beauty and physical fitness is constantly increasing, and to meet that goal people take a variety of measures. A quick glance inside a fitness magazine quickly reveals that dietary supplementation is an immensely popular method of achieving a better physique. It seems as if every other page of these magazines is an advertisement for a pill or powder that can make users run faster, lift heavier, or drop weight effortlessly. In the fitness world, countless supplements make promises of better performance and faster results, but their ingredients and efficacy are largely unregulated. Some companies conduct third-party tests and clinical studies to reinforce their claims, but there are no major dietary supplements (DS) that are approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The FDA does not require supplement manufacturers to register their products or obtain approval prior to releasing them on the market. In lieu of official registration, the FDA has strict guidelines on what can and cannot be sold as a dietary supplement and regulates "product information, such as labeling, claims, package inserts, and accompanying literature" (FDA 2012) to protect consumers from harmful products. DS manufacturers are responsible for ensuring the safety of their products, adhering to guidelines of quality control and packaging, and reporting major adverse effects, but the FDA does not check that all products meet the guidelines. Because of this, potentially harmful side effects may occur from products that were not thoroughly tested. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is the regulatory body for advertising of dietary supplements. The FTC ensures that claims made by supplement advertisers have proper substantiation to protect the public from misleading or false advertising, and those familiar with dietary supplements will know the phrase "this claim is not supported by the FDA" contained in many DS ads and labels. But neither the FDA nor the FTC provides regulations on the amount of information manufacturers and advertisers need to provide for their audiences through advertising. No standing guidelines require advertisements to tell consumers the ingredients of a supplement or how that supplement works, so many ads neglect to do so. Even with the knowledge that the government does not substantiate claims made by supplement producers, consumers are still willing to pay for the possibility of a better body. The desire to achieve an ideal physique is strong enough to sell supplements even with no guarantee of results and the accompanying risk of harm. This research aimed to study the relationship between the egotistical or social desire to be physically fit and dietary supplement advertisements. Using content analysis of magazine advertisements for dietary supplements, this study compared the type of appeal used in advertisements, as defined by Taylor's SixSegment Message Strategy Wheel, with the amount of quality information regarding effects and ingredients of the supplements. II. Literature ReviewThe Dietary Supplement Industry and Advertising Regulation The dietary supplement industry in the U.S. has grown steadily over the past 20 years with 49% of the population reporting they have used at least one supplement. In 2010, DS industry revenue was estimated to be $27.9 billion and the same source predicted that its revenue in 2016 would reach $34.7 billion. There are approximately 30,000 different DS products available in the U.S., with 1,000 more being introduced every year. Despite the prominence of this industry and frequency of DS use by a majority of people, 52% of users are unaware that these products are not government approved or evaluated, according to a survey by Ashar and others (as cited in DeLorme, Huh, Reid & An, 2012). Dietary Supplements are defined as "any product designed to supplement the diet that bears one of the following ingredients: a vitamin, a mineral, a herb or other botanical agent, an amino acid, weight-loss supplement, or herbal remedy" (Main, Argo & Huhmann, 2004, p. 29). These supplements fall under their own regulatory area under the United States Food and Drug Administration as they are not subjected to the same standards of medical drugs or food products . The 1994 Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) redefined the classification of DSs, putting them into a unique category as neither a food nor a drug. Under DSHEA, the safety and efficacy of DSs didn't have to be approved or evaluated by the FDA before being marketed to the public and it became the responsibility of the FDA to demonstrate a product is unsafe before taking action against a manufacturer. The FDA is also charged with regulating the labeling of DSs, ensuring the claims on labeling fall within one of three allowable categories: health, nutrient content, or structure/function (DeLorme et al. 2012). While labeling is covered by the FDA, advertising for DSs falls under the jurisdiction of the Federal Trade Commission. The FTC's regulations hold supplement advertising to the same truth-in-advertising standard as it does all advertisements, requiring all claims to be supported by "competent and reliable scientific analysis" (US FTC, 1998). Guidelines put forth by the FTC in 1998 extensively describe the requirements for substantiating claims made in supplement advertising, but anything beyond ensuring the accuracy of claims is left up to self-regulation within the advertising industry (DeLorme et al. 2012). Self-regulatory bodies such as the National Advertising Division and Council for Responsible Nutrition "review nationally disseminated advertising for truth and accuracy" (Villafranco & Lustigman, 2007) and have recently made increasing efforts to scrutinize DS advertising (DeLorme et al. 2012), but these organizations continue to focus on the same areas as the FTC. There are no regulatory bodies that monitor the message content of DS ads beyond the validity of the products claims. Message Strategy in Supplement Advertising The current study aimed to fill in the gap in research pointed out by DeLorme et al. (2012) "regarding the balance of information and persuasion" in DS advertisements. Previous studies have suggested that because dietary supplements have the potential to harm consumers, DS advertisements can pose a threat if they do not adequately or accurately inform consumers about the product. One study showed that 60% of regular DS users were likely to believe the ad claims, and many had such strong beliefs that they would continue taking them even if the products were demonstrated to be ineffective (Blendon, DesRoches, Benson, Brodie & Altman 2001; DeLorme et al. 2012). Williams' article in the Journal of Exercise Physiology (2004) gave a unique perspective on the health risks associated with the advertising of fitness supplements. She asserted that the over-idealized images used to advertise supplements and a lack of quality information about the products are a dangerous combination. Another study by Main et al. (2004) compared message appeals in prescription drug advertising to that of over-the-counter medicines and DSs, classifying the ads visuals and headlines as emotional or rational appeals. A rational appeal was defined as "a factual presentation" of a product that tends to motivate consumers through informational and logical arguments while an emotional appeal is generally defined as attempting to evoke an affective response to influence consumer attitudes and choice behavior. They found that emotional appeals were used in 56.6% of DS ads, while rational appeals appeared in only 43.5% of the ads. Dietary supplements only appeared briefly for comparison to the medical drugs being studied in Main, leaving a gap in the research between DSs and their more regulated medical counterparts. To more completely evaluate the message strategy in DS advertisements, this study utilized Taylor's Six-Segment Message Strategy Wheel as a theoretical model. Taylor's model combines a multitude of psychological and communication theories to produce the most comprehensive model of its kind. Chart 1: Taylor's Model

Taylor's model (Chart 1) is based on a combination of Transmission and Ritual models of communication. It is also frequently referred to as informational and transformational models or stated previously as models based on rational and emotional appeals. Taylor took these theories further, breaking each down into 3 more segments. The ego segment of Taylor's model is defined as advertising to the individual's sense of self. The social segment appeals to a sense of belonging and social approval. The sensory segment focuses on a rewarding experience of one of the five senses. The ration segment contains the most logical appeals, often including the "reason why" copy. Acute Need refers to situations where consumers must purchase now and don't have time to gather information before making a decision. In the routine segment, ads will provide a cue for how consumer needs can be met and try to create a habit or routine. For this study, the author formulated two research questions: RQ1: What segment of Taylor's Six-Segment Message Strategy Wheel do dietary supplement advertisements fall under most frequently? RQ2: What is the relationship between the main appeal of an advertisement and the amount of information provided in the ad?Continued on Next Page » Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in Business & Communications |