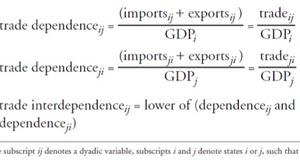

Featured Article:Globalization's Peace: The Impact of Economic Connections on State Aggression and Systemic ConflictAnalysisWhat follows is a description of how this study’s statistical analysis will be undertaken, including a specification of the variables, sampling scheme, and compilation of data. I then turn to a discussion of my findings, including all relevant statistical summaries, and whether the data supports the hypotheses that are the focus of this research. Operational DefinitionsIn order to empirically evaluate the relationship between the degree of states’ trade and investment and their likelihood to initiate conflict, this study’s variables need precise definitions. For my first two independent variables, I measure states’ trade in terms of imports and exports as percentages of their Gross Domestic Product (GDP), with data obtained from the World Bank (2011). The use of imports and exports as percentages of states’ total GDP is appropriate because it allows me to measure the extent to which a state is dependent on involvement in the world economy for revenue, domestic employment, resources, etc. The second two independent variables tested here are total inward and total outward FDI, for which I use data from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (2010). I chose total FDI (in millions of current U.S. dollars) because it measures the true degree to which foreigners invest in a state’s economy, along with the extent to which a state’s citizens invest in other states’ economies. FDI as a percentage of GDP would not really give a sense of what I am looking to measure; in countries with small or large economies, it would be difficult to compare inward and outward FDI as percentages of GDP. Total FDI gives a sense of what would be at stake if a state initiated a conflict—that is, how much FDI could be lost if foreign investors decide to terminate their investments. With regards to dependent variables, this study uses two: First, the total number of violent disputes that a given state has initiated, and second, its total “degree of hostility” based on how aggressive its initiated disputes were. The Correlates of War (COW) data set is used to operationally define these variables. This study uses what COW terms “militarized interstate disputes” (MIDs)—which it defines as instances in which one state threatens, displays, or uses force against another—to measure and code instances of state aggression (Ghosn and Bennett 2007). The total number of MIDs initiated gives a sense of state aggression; however, also used here is a measure I term “degree of hostility.” COW rates each MID on how hostile it was, ranging from +1 (“no militarized action”) to +5 (war), but because I am only focusing on interstate military conflict, I only aggregate the ratings from +2 (“threat of force”) through +5. For the sake of measurement, I code states’ MIDs on a scale of +1 through +4 for a state’s total “degree of hostility.” In the same manner, when totaling the total number of MIDs that a state has initiated, I only include those that COW rates as +2 through +5.Table 1: Coded Values of MIDs

Data CompilationThis study examines the period from 1980 through 1999. Given that this era saw the rise of a “Washington Consensus” stressing trade liberalization and market deregulation, and the beginning of what has come to be called “globalization,” it is an appropriate period in which to analyze the impact of trade and international economic connections upon state aggression (Stiglitz 2002). For the purposes of comparing data across the entire stretch of time, I break the period down into four individual five-year blocs, starting with 1980 through 1984. I then analyze a random sample of thirty percent of all countries in each given time bloc, adding them as needed. The ways in which I code the values of my independent and dependent variables reflect my use of five-year blocs. For the independent variables of imports and exports (as a % of GDP) and total inward and outward FDI, I use each sampled case’s mean value for that variable in the five-year period. However, with regards to my dependent variables I simply total the number of MIDs each country initiated and its total degree of hostility for that time bloc. My first hypothesis is that the higher a state’s levels of imports per GDP, exports per GDP, FDI outward, and FDI inward are in a given 5-year-bloc, the lower that state’s numbers of MIDs initiated and total degree of hostility should be in that time period. I use ordinal categories to denote each state’s values for all four independent variables and both dependent variables. The ordinal categories used for exports, imports, and inward and outward FDI are “High,” “Medium,” and “Low” and I divide each time bloc’s values accordingly (i.e., a state in the top third of imports/GDP in a given bloc would be ranked as “High,” etc.) For my dependent variables, I use the ordinal categories “None” (as in no MIDs initiated), “Low,” “Medium,” and “High.” States that initiate one or two MIDs are rated as “Low,” those that start three or four as “Medium,” and those that have five or more instances of aggression in a given time bloc are rated as “High.” Similarly, a degree of hostility between one and four is treated as “Low,” between five and nine as “Medium,” and ten or more as “High.” Table 2: Variable Classification, Hypothesis 1

The use of ordinal variables allows me compare values across the time span, as they provide an efficient means of standardizing the data of all the 5-year blocs throughout the 20 year period. Once I have determined the values of each case for each bloc, I then aggregate the totals of all four time blocs (e.g., all cases in which a country with “Low” inward FDI initiated a “Medium” amount of MIDs) into a contingency table of the totals for the entire 20-year period. I control for the effects that a country’s wealth might have on its propensity to initiate conflict. Cases are divided in half on the basis of their level of GDP per capita, in 2011 US dollars, with data obtained through the World Bank (2011) and, for Taiwan, through the Penn World Table (2011). The second hypothesis is that the greater the entire international system’s average levels of imports/GDP, FDI inward, etc. are in a given 5-year-bloc, the lower the average amount of MIDs initiated and degree of hostility in the international system should be in that time bloc. In order to test this relationship, I plot the per capita value (i.e., per state) of each independent variable for all four time blocs against the per capita value of both dependent variables. I then calculate the correlation and slope of the relationship between overall international economic interconnectedness and overall international aggression for each time bloc. Unlike for Hypothesis 1, I do not aggregate the values, for in order to test Hypothesis 2, I must be able to see how all of the variables changed over time—and whether systemic changes in economic connections produced changes in systemic aggression. Table 3: Summarization of Hypotheses

Hypothesis 3 posits that increases in overall economic interconnectedness (FDI inward, exports per GDP, etc.) should lead to military disputes that are on the whole less hostile, and it is tested here in the same manner as Hypothesis 2. In order to find the average hostility of initiated MIDs, I divide the total degree of hostility of a given 5-year-bloc by the total number of MIDs initiated in that bloc. For example, if the total degree of hostility is 108 and the total number of MIDs initiated by sampled countries is 54, average hostility would be 2 on the 1 through 4 scale. This value then becomes the dependent variable in each bloc that is, as in Hypothesis 2, plotted against each time bloc’s mean value of all four independent variables. Thus, a mixture of ordinal and interval variables are used to analyze the three hypotheses tested here. Hypothesis 1 relies upon an aggregation of all cases throughout all four time blocs in order to determine whether individual states’ economic connections tend to decrease their likelihood of aggression. On the other hand, Hypotheses 2 and 3 look at how the entire international system’s economic interconnectedness and levels of aggression have changed over time—and whether they have co-varied. In reality each is a variant on the same question: whether globalization and international economic ties contribute to a more peaceful world. Data AnalysisOn the whole, my findings are largely supportive of what was expected; although they simultaneously uphold and contradict my hypotheses, my predictions were mostly confirmed.4 I start with an evaluation of Hypothesis 1. As noted in Table 4, contrary to expectations, states with higher amounts of inward FDI tend to be more aggressive than states with lower amounts. Wealthier countries’ levels of inward FDI on the one hand, and their total MIDs and overall degree of hostility, on the other, have a moderately positive relationship, with Gamma correlations of 0.43 and 0.39, respectively.5 Those of poorer countries have similar—though slightly stronger—positive relationships for those same variables, with Gamma correlations of 0.54 and 0.53. With regards to all other tested relationships in Hypothesis 1, however, only those of the wealthier countries proved to be conclusive, as none of the other six combinations of independent and dependent variables were significant past the .05 level for poorer countries. It is to the wealthier countries, then, that I turn to now. States’ outward FDI, much like their inward FDI, is positively associated with their number of initiated MIDs and with their degree of hostility. Thus, outward FDI’s relationship with state aggression contradicts the anticipated one, as sampled states’ outward FDI has a Gamma correlation of 0.47 with their initiated MIDs and a correlation of 0.45 with their hostility. Both measures of FDI, then, seem to cause states to be more aggressive relative to one another, and thus violate the predicted relationship. Table 4: Gamma Correlation Values of the Relationships Between State Economic Connections and Aggression, 1980-1999

However, imports and exports as percentages of GDP are, as hypothesized, negatively associated with aggression for wealthier countries. Both imports and exports have Gamma correlations of around -0.5 for both states’ total initiated MIDs and their degree of hostility. It should be noted, however, that both imports and exports’ negative relationship with states’ total initiated MIDs are not quite significant past the 0.05 levels, but given that both are negatively correlated with states’ degree of hostility (which is significant), it seems safe to say that states with higher levels of imports per GDP and exports per GDP are less aggressive. Thus, Hypothesis 1’s predictions are half-supported—whereas FDI is associated with greater chance of aggression on the part of states, trade is associated with diminished state aggression. Hypothesis 2, on the contrary, is fully supported. As Table 5 shows, international levels of exports and imports as percentages of GDP, FDI inward, and FDI outward are all negatively associated with systemic aggression. All four indicators have at least moderately strong negative impacts on both systemic MID initiation and systemic degrees of hostility; imports’ relationships have correlations of around 0.85 with these two measures of conflict, those of exports, around 0.75, and those of inward and outward FDI around 0.5 and 0.6, respectively.6 The regression coefficients suggest that the magnitude of the relationship is substantial as well; for every one percent increase in the international system’s average imports or exports per GDP, and for every billion dollar increase in FDI inward or outward, the number of per capita MIDs decreases by an average of 0.1. Table 5: Pearson's r and Regression Values of the Relationships Between Systemic Economic Connections and Systemic Aggression, 1980-1999

Regarding Hypothesis 3, Table 6 indicates that greater international levels of all four measures of economic interconnectedness result in less average MID hostility. Each of the four independent variables is highly correlated with lessened conflict intensity; the correlation values of imports and exports per GDP’s relationships even top 0.9. These findings support Hypothesis 3 completely; moreover, they refute the study of de Vries (1990, p. 431), who finds that economic interdependence is “a catalyst increasing the intensity level of international relations in both conflictive and cooperative situations.” Rather, as predicted in Hypothesis 3, economic interconnectedness mollifies conflicts by reducing the likelihood of their escalation. However, for each relationship, the regression coefficient is quite small; it would take a ten percent increase in worldwide imports and exports per GDP for average hostility to drop by 0.2, and a ten billion dollar increase in FDI inward and outward for it to drop by 0.3 and 0.2, respectively. The results indicate that world trade and FDI must dramatically increase for even the smallest appreciable decline in average conflict hostility. Thus, while economic connections do appear to lessen average hostility, the magnitudes of the relationships are so small as to be almost insignificant. Table 6: Pearson's r and Regression Valyes of the Relationships Between Systemic Economic Connections and Average Hostility, 1980-1999

ImplicationsThe overall implication of this study is that the liberal perspective, upon which this model is based, is for the most part supported; trade is shown to decrease state aggression, while both trade and FDI decrease aggression and average conflict hostility at the systemic level. However, greater levels of inward and outward FDI seem to increase states’ likelihood to initiate conflict. What follows are possible reasons for why these two indicators do not have the anticipated effect on aggression at the monadic level of analysis. First, with regards to FDI inward, Millen and Holtz (2000, pp. 171-172) note that FDI inward need not necessarily be beneficial to the target of the FDI, and Gasiorowski (1986, p. 34) even argues that FDI can threaten the sovereignty of the states that are invested in by putting ownership of key industries in the hands of foreigners. In this light, FDI’s positive relationship with aggression could simply be a function of states’ vulnerability and resentment as they seek to break free of their dependencies through conflict—whether it was intended to be military in nature at the outset of hostilities or not. In this case, the findings would thus be consistent with the neorealist perspective. Second, with regards to FDI outflows, it is unclear why higher levels of it should increase aggression at the state level. One possibility is that states with high levels of FDI outward will be “dragged into” conflicts by domestic forces seeking to ensure that their investments abroad remain secure, as is sometimes alleged about the interventions of the United States in South America and the Caribbean. It is possible that this scenario may only apply to source countries that are democratic, as the concerns of domestic constituencies would likely have more impact in a democratic system. This is merely hypothetical, however; more research is needed to shed light on the dynamics of how investment patterns enter into states’ security calculations. Ultimately, my findings indicate that the model used here is useful for predicting interstate conflict—the fear of economic penalties, such as sanctions, appear to be a deterrent to the initiation of conflict on the part of heavily trade-dependent states. Although the liberal perspective is not entirely supported—as seen in FDI’s positive impact upon state aggression— what does seem to be clear is that the classical realist school of thought is inadequate when it comes to predicting the impact of economic connections on state aggression. With the exception of the inconclusive data on poorer states, the findings detailed above indicate that the classical realist assumption about trade’s irrelevance to conflict is unrealistic. When the results of Tables 4 through 6 are compared, it is clear that there is no simple relationship between a country’s economic ties and its likelihood to initiate conflict. However, on the whole, interconnectedness is associated with reduced conflict. Imports and exports are shown to decrease state aggression, and economic connections are overall associated with less systemic conflict and conflict intensity. The data provides hope that, in the future, economic bonds may indeed be the bonds of cooperation and peace.Continued on Next Page » Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in Political Science | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||