China's International Investments Under Xi Jinping: Long Term Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative and Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank

By

2022, Vol. 14 No. 01 | pg. 1/1

IN THIS ARTICLE

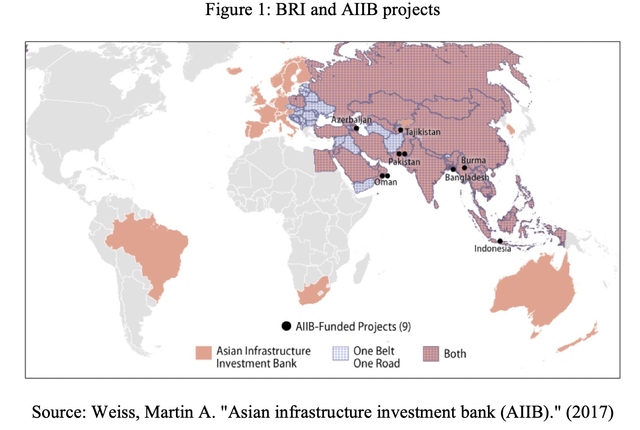

AbstractThe study examines the degree to which Xi Jinping has brought about a strategic shift to the Chinese outward investment pattern and how this may present significant political leverage and military advantages for China in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR). In order to understand China’s intention behind its outward investments, the study examines the numerous outbound investments made by Chinese businesses and state-owned enterprises, especially in the infrastructure and energy sector, and demonstrate a strategic shift brought by Xi Jinping to achieve his domestic objective, which can be seen through the two signature initiatives launched by Xi Jinping: the Belt and Road Initiative, and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), which plan on investing $8 trillion in at least 68 countries. This study indicates that these initiatives may eventually leave the countries with a debt problem that will be unsustainable and create an unfavorable level of dependency on China as a creditor, signs of which have already been seen in Djibouti and Pakistan. Finally, the study concludes with the efforts taken by the international community to counter China’s growing political and military leverage in IOR. IntroductionSince 1978, China has undergone multiple political and economic reforms, which have transformed China’s trajectory, enabling it to rise as an economic superpower. The economic reforms of 1978 conveyed the beginning of the end of the Maoist version of a centrally controlled economy by increasing the role of market forces and reducing government planning and direct control.2 Finally, in 2000 with the introduction of the “Going Out Strategy,” China bid farewell to the Mao-era mentality of self-reliance, where resources were allocated to lower-level administrative units such as provinces, districts, counties, prefectures, and rural collectives, and encouraging them to improve their economies. This shift was undertaken to resolve resource insecurity and take advantage of the booming world market.3 Under Xi-Jinping’s leadership, the Strategy has evolved to echo its domestic goal of “great rejuvenation of the Chinese Nation” by creating a sphere of influence in the international community and while simultaneously safeguarding its rights and interests.4 Within a year of assuming power, Xi Jinping launched two of his signature foreign policy initiatives: the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI, formerly known as One Belt One Road), seeking to build up trade, infrastructure, investment, and human linkages across Eurasia and Africa, and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), a multilateral bank intended to overcome dependence on Bretton Woods institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and World Bank. These initiatives enabled China to penetrate the global economy along with investment and trade agreements, thereby growing China’s economic footprint. Moreover, a significant part of these investments aims to develop infrastructure, especially ports across Asia and Africa, bolstering China’s military presence.5While China plans on investing $8 trillion in at least 68 countries within a decade, these programs may eventually leave the countries with a debt problem that will be unsustainable and create an unfavorable level of dependency on China as a creditor. The continuous cycle of debt created by China will enhance its regional and global influence, regardless of a state's resentment towards the debt due to its dependence on China. On the other hand, while this action plan may seem persuasive enough to be followed, in reality, a partnership whose foundation is laid in economic coercion is likely to be politically and strategically unstable. A case in point being Sri Lanka, where commercial investment by Chinese state-owned enterprises and the intermittent visit by People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) vessels have already proven to be politically fraught.6 The conditions created by these investments lay the groundwork for leveraging its commercial infrastructure for intelligence collection and forging robust-surveillance information-sharing agreements with countries in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR). China’s growing commercial activities and economic influence over other states in the IOR serves as a forewarning of China’s ability and ambition to operate high-end military missions. The signs of debt distress due to BRI projects have started to appear in Djibouti and Pakistan, as they eventually might be coerced to make a debt-for-equity swap deal as in Sri Lanka or Tajikistan case of debt cancellation in exchange for territory. China can leverage its monetary investments in the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor to pave the path for military access to the strategically located Gwadar port for the PLAN.7 This study examines the degree to which Xi Jinping has brought about a strategic shift to the Chinese outward investment pattern and how this may present significant political leverage and military advantages for China in the IOR. In order to do so, the study surveys the numerous outbound investments made by Chinese businesses and state-owned enterprises since 2005, especially in the infrastructure and energy sector. It involves creating a framework to distinguish the investment trends before and following Xi Jinping assuming office as President of the People's Republic of China in 2013. This provides the ability to prove the strategic shift brought by Xi Jinping to achieve his domestic objectives. Moreover, the study looks at the agreements signed by states in the IOR with BRI and AIIB to find the terms and conditions on which China has invested in these states. It provides information about China's scope and power when states fail to pay back and fall into a debt spiral. This information is essential to understand a state's likelihood to tumble into a debt-trap and give in to Chinese demands, allowing China to gain leverage and influence over states in the IOR. The study focuses on the effort made by China has attempted to gain political leverage and military advantage through the dual-use of investments and driving states into a situation of debt distress, leaving them vulnerable to Chinas influence. However, while utilizing debt-trap and dual-use investment may seem compelling, agreements grounded in financial intimidation may create political and strategic instability. The study lastly investigates the strategic ramifications of these investment and implication for other states. BackgroundSince the People’s Republic of China’s foundation in 1949, China’s economic growth has been tumultuous and inconsistent. Under the leadership of Mao Zedong (1949-1977), China’s aimed at reducing social inequality, overhaul land ownership and restore the economy, which has been devastated by the war through a centrally planned economy. Economic output and allocation of resources were controlled and directed by the state. It was Mao’s goal to make China self-reliant and -sufficient; thus, foreign trade was limited to goods that could not be produced or obtained in China. Mao introduced a communal farming system to balance the growing industrialization and agriculture output. The economy was distorted as a result of such policies. There were few incentives for companies, employees, and farmers to become more profitable or concerned about the quality of what they generated because most parts of the economy were regulated and run by the central government.8 As a result, there were no competition structures to distribute capital effectively, and hence there were few incentives for firms, staff, and farmers to become more productive or concerned about the quality of what they produced. Shortly after the death of Mao in 1978, the Chinese government under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping disregard certain Mao-era tenets of economic policy and reform them based on the principles of free-market and opening up the economy to trade and investment. These reforms were brought after the failure of ten-year Cultural Revolution in 1966, where anything related to capitalism or "bourgeois"ideals was removed, which crippled the country politically and economically. Deng Xiaoping put these reforms as: “Black cat, white cat, what does it matter what color the cat is as long as it catches mice?” as a means of assuring the country that no matter what kind of economic policies Chinapursues, the only thing that matters is that the economy grows. The central government provided farmers with price subsidies and ownership incentives, enabling them to sell a portion of their crops in the open market. Furthermore, they created special economic zones (SEZs) to attract foreign investment, boost export, and import new technology into the country. Gradually, the economic control was handed over to the local and provincial governments, allowing them to operate and compete in a free market rather than under the supervision of the state and state price controls eliminated on a wide range of goods and services. In addition to this, citizens were empowered to start their own businesses by offering tax and trade incentives. Before 1978, the economy was growing at an annual average of 6.7%, according to official Chinese government statistics (critics have argued that the government has exaggerated the numbers for political reasons, and the annual average growth rate is somewhere near 4.4%). After implementing structural reforms, China’s economy has expanded much faster than it did before reform and, for the most part, has prevented major economic shocks. Since 1979, the Chinese economy has been growing at an annual average of 9.5%. In other words, China has been able to double its economy in real terms every eight years.9 Large-scale infrastructure spending (financed by significant domestic savings and foreign investment) and strong productivity growth are the two primary drivers of rapid growth. Despite China’s remarkable economic growth over the next two decades, restructuring the state sector and modernizing the banking system remained significant challenges. More than half of China’s state-owned enterprises were dysfunctional and losing money. President Jiang Zemin decided to lose the dead weight created by the state-owned enterprises by either selling, merging, or closing them. Within three years, the majority of the previously owned state-owned enterprises were now profitable.10 After almost two decades of decentralization and allowing foreign companies to invest and trade in China, it had accumulated vast foreign reserves, placing upward pressure on the Renminbi, the official currency of China. Moreover, local Chinese firms were competing in a pitched battle against foreign multinational cooperation’s in China, with no external support from the government. Thus, in 2000, Zemin introduced the “Going Out Policy” (also known as “Going Global Strategy,” “Going Out Strategy” and “Go Out Policy”) to encourage its Chinese firms to invest overseas, allowing China to employ its foreign reserves by acquiring assets overseas and equip domestic firms with international experience, to take the balance the competition in the world market.11 Apart from FDI outside of China, the ‘going out strategy prompted local companies to begin extending their activities by creating multinational supply chains for distribution. State-owned companies played a crucial role in rallying support for this initiative.12 However, there were few target areas of this initiative, which were granted export tax rebates, financial assistance and foreign exchange assistance, and other incentives when tapped by local firms. The National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) and the Export-Import Bank of China (EIBC) jointly released a circular in October 2004 to stimulate foreign investment in specific areas: “(1) resource exploration projects to mitigate the domestic shortage of natural resources; (2) projects that promote the export of domestic technologies, products, equipment and labor; (3) overseas R&D [research and development] centers to utilize internationally advanced technologies, managerial skills and professionals; and (4) [mergers and acquisitions] that could enhance the international competitiveness of Chinese enterprises and accelerate their entry into foreign markets.”13 Interest in overseas investment by Chinese companies has increased significantly since the start of the Going Out Policy, especially among State-Owned Enterprises. China’s outward direct investment grew from US$ 3 billion in 1991 to US$ 35 billion in 2003, and by 2007 it had reached US$ 92 billion.14 State-owned companies continue to account for the majority of China’s outward direct investment. State-owned enterprises under central supervision produced around $38.2 billion (67.6%) of total Chinese outward direct investment in 2009, whereas the gross outward direct investment flows were $345 million (or 0.6 percent) by 33 private companies, while the rest came from joint partnerships between state and private companies ($17.95 billion).15 This expansion of overseas investment has allowed China to gain access to foreign raw materials and advanced technologies, raise foreign exchange earnings, and promote China’s exports. To sustain China’s strong economic growth rate, gaining access to overseas energy supplies and raw materials remains a vital strategic driving force. In the case of aluminum, copper, nickel, iron ore, and other primary commodity goods, a similar image of the exponential rise in demand from China is growing. This can be seen through influential policy-setting National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), requiring China’s energy companies to purchase equity in upstream energy suppliers, primarily through overseas acquisitions like in the case of China’s fourth-biggest producer of the fuel, Yanzhou Coal Mining, which bought Australia’s Felix Resources Limited in 2009 for $2.9 billion, to secure supplies.16 Local firms are encouraged to form joint ventures or buy international firms in order to acquire cutting-edge technology and thereby “leapfrog” many phases of growth and upgrade, a prime example being Lenovo’s purchase of IBM’s personal computer division in 2005. Chinese businesses often check out for bargains in the American or European markets, companies with high name awareness but weak financial standing, and buy them as a means to establish a foothold in established markets and acquire marketing skills.17 Like the 1978 economic reforms reached their peak in the late 1990’s, the “Going Out Policy” reached its peak by the early 2010’s. Projects were hampered by economic and governance challenges, rarely breaking even. Most of the state-owned enterprises were filled with corruption and the rent-seeking rooted culture. Failure to comply with local norms and practices like in the case of China Overseas Engineering Group, when Poland hired them to construct a highway for almost half a billion dollars, they failed to include the culverts that are needed to enable small animals to travel under the road, which ultimately led to the cancellation of the project. Global demand fluctuations, especially in western countries after the 2008 financial crisis, aggravated macroeconomic issues.18 Understanding the strategy issues, China, under Xi Jinping’s leadership, took a different approach and launched the Belt and Road Initiative and Asian Investment Bank. China under Xi JinpingWith the world developing at an unprecedented rate of 4.3% after the economic crash of 2009, there was an increasing need, both at home and abroad, for China to change its diplomatic structure and welcome the historic transition of its relationship with the rest of the world. The shift began at the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China in 2012, when Xi Jinping succeeded Hu Jintao as General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party. Under Xi Jinping Chinese diplomacy underwent a significant transition with the realization that China needs to change with the world and replaced its “tao guang yang hui” [keeping a low profile] strategy with a “fen fa you wei” [striving for achievement] strategy. After the first stage of "revolution diplomacy" under Mao and the second stage of "development diplomacy" under Deng Xiaoping, China has reached the third stage of “going out diplomacy” under Xi Jinping's leadership.19 The conceptual mechanism for constructing the “Silk Road Economic Belt” and a companion “21st Century Maritime Silk Road,” collectively known in Chinese parlance as the “One Belt, One Road” (OBOR) (now known as BRI) initiative, is a direct demonstration of this transformation.20 In official Chinese statements, BRI represents a

It is the vehicle by which China plans to expand connectivity with over 65 countries and more than 30 international organizations, centered in part on the ancient Silk Road land and maritime routes. The economic aggregate of the BRI economies is approximately $21 trillion, representing 65 percent of global output revenue and 30 percent of global maritime trade. The initiative seeks to strengthen these ties by investing in infrastructure, establishing transportation and economic corridors, and linking China to other countries “physically, financially, digitally, and socially.”22 The introduction of BRI is based on two considerations. First, China's robust economic development over the last two decades is starting to cool down. Owing to an increasingly ageing population, a declining birth rate, a tightening Federal Reserve, and a weakening global economy, China's growth rate dropped by nearly half from 14.23 percent in 2007 to 7.86 percent in 2012.The BRI represents an opportunity to re-energize expansion, reduce energy insecurity, and boost China's global footprint and reputation while ensuring that China retains the potential to self-fund many of the initial BRI ventures. Furthermore, the BRI provides a lifeline to inefficient state-owned enterprises. From 2013-216, the share of loans secured by state-owned enterprises from state-owned banks increased by 45.6% in order to fund BRI projects.23 Second, the BRI stems from China's discontent with the status quo, at least in its own area. China's military buildup, accumulation of power over political and economic decisions in the IOR, and actions against international financial institutions such as World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) all suggest discontent with the status quo.24 China's adamant emphasis on being viewed as a developing nation is a major source of discontentin its trade ties with advanced economies and organizations. Another source of conflict with IMF and World Bank comes from China's non-compliance with universal standards and norms in its bilateral trade ties with other developed countries.25 BRI represents a transition in China's "going out" policy as part of the country's attempt to change its economic growth paradigm. Although the early years of the “going out” strategy stressed the procurement of necessary components to boost China's heavy industry, investment-led, and export-oriented economy, this seemed to limit the effort's target countries to resource-rich countries primarily in Latin America and Africa. The redesigned “going out” strategy prioritizes initiatives to help China's economy climb up the value-added chain in every possible economic segment, broadening the effort's reach and ambition. BRI not only allows China to extend its reach abroad, but it is also accompanied by a domestic investment push in which virtually every Chinese province has an interest.26 After a year, at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation meetings in Beijing, Xi Jinping announced that China would create a $40 billion fund to help finance the development of the BRI.27 The Bank of China, which has the most extensive international networks, announced plans to expand credit to BRI-related projects worth no less than $20 billion in 2015 and $100 billion between 2016 and 2018.28 By 2019, the Bank of China had sanctioned over $140 billion in credit and had financed over 600 big BRI ventures. It has founded overseas institutions in 24 of the initiative's affiliated countries and regions.29 China has made a persuasive contribution to the BRI initiative for a more open world economy by establishing the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), and the Silk Road Fund (SRF), among other government-led initiatives, with the goal of being a significant, if not a key, part of globalization in the new century. Moreover, China has developed new multilateral and domestic Chinese institutions to finance BRI, especially the China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China. Under BRI, the Chinese investment estimate varies from $1 trillion to $8 trillion US dollars, with $1 trillion being the most widely quoted figure.30 The catalyst for China's establishment of the AIIB stemmed from frustration with the governance of established international financial institutions, mainly an inadequate "focus on infrastructure and growth." The Bank's stated aim, as its name implies, is to provide funding for infrastructure needs in Asia and neighboring regions. The Bank establishedin 2013, and started operations in mid-2016, has 57 founding members, including four G-7 economies (France, Germany, Italy, and the United Kingdom).31 The AIIB's Articles of Agreement state:

The AIIB's initial gross funding is $100 billion, with 20% of the shares are paid-in, thus has to be passed on to the bank, while the rest remaining 80% of the shares are callable on demand, depending upon the project. The shares are distributed using the GDP Nominal of 60% and GDP Purchasing Power Parity of 40%, depending on the size of each member country. The approved capital fraction in the bank is also determined by the amount of shares. China is investing $50 billion, or half of the original capital subscribed. India is the second-largest shareholder, with an $8.4 billion investment. The Bank is headquartered in Beijing, China, and is led by Jin Liqun, a former Chinese vice-minister of finance, chairman of a Chinese sovereign wealth fund, and ADB vice president.33 As the AIIB membership grew, Chinese officials distanced it from China's BRI strategy in order to get broader recognition and support from international community. During a meeting with global executives in June 2016, AIIB President Jin Liqun explained China's stance, stating that while the Bank will fund BRI ventures, the AIIB was not established solely for this purpose. President Xi made the remarks while attending the World Bank's spring 2016 meetings in Washington, DC, "We would finance infrastructure projects in all emerging market economies even though they do not belong to the Belt and Road initiative."34 In addition, AIIB began collaborating with the New Development Bank (NDB), a multilateral development bank founded by the BRICS countries, to meet development and infrastructure needs. The AIIB and NDB collaboration is targeted at improving infrastructure with a focus on long-term sustainability in the BRICSand BRI states. The banks form a financial, regional, and local collaboration network with multilateral and national development banks, as well as other institutions and market participants. To meet Asia's rising infrastructure demands and contribute to the region's social and economic growth, the banks are leveraging their partnerships with other multilateral development banks and private financiers. Compared to the AIIB, China's policy and commercial banks have a more flexible choice for funding BRI projects, which is especially important to China's interests. Policy banks work as “agents of Chinese state-capitalism that employ subsidized capital to achieve a combination of commercial and geopolitical aims.”35 Infrastructure, energy, and transportation programs are all funded by the China Development Bank.36 The Exim Bank focuses on trade finance and the promotion of Chinese goods and services, all of which are important to China's state-owned enterprises.37 The AIIB was projected to lend $10 billion to $15 billion every year over the first five or six years, and its establishment was seen as further evidence of the world economy's rebalancing from West to East. However, according to a 2018 survey, the AIIB has only loaned a little more than $3.5 billion to date, with only one-third of it appearing to be linked to BRI. In comparison, the China Development Bank and Exim Bank announced lending around $102 billion and allocating “hundreds of billions in BRI-related credit.”38 The Silk Road Fund, which also finances BRI ventures, is affiliated with the People's Bank of China and has a total capitalization of $40 billion. State Administration of Foreign Exchange, China Investment Corporation, Exim Bank of China, and China Development Bank are among the four Silk Road Fund members.39 Since becoming General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, Xi Jinping has been pushing the “Chinese dream," which is best exemplified by the BRI and AIIB. The “Chinese dream” is a unifying element for the Chinese to pursue a great national rejuvenation to build a prosperous society and alter the global environment, which has been dominated by Western countries since industrialization throughout the last two centuries. A top-down political strategy to promote the dream was launched in the party, and it has since become a recurring theme in the majority of Xi's public speeches. In an attempt to make a statement, Xi Jinping's "Chinese dream" is part of the new Chinese leadership's effort to ensure domestic peace and retain power and prestige at home. When public outrage and demonstrations erupted around the country in 2012 due to growing economic disruptions in the country, the "Chinese dream" offered an impetus to mobilize or organize the Chinese people and launch anti-corruption and rectification efforts to demonstrate commitment and clean-up the party. It enabled Chinese people to look past the country's immediate problems of slowing economic growth and lack of consumption, by providing them with a vision for China's growth over the next several decades.40 Xi Jinping has emphasized many times in his speeches on the "Chinese dream" that China, as a significant force, should have a proper perspective and approach to defending "justice" and pursuing "interests" in the international community. It encourages China to pursue their own desires in order to achieve greater growth while still considering those of others.41 By spreading the “Chinese dream” internationally as a continuation of China's peaceful growth strategy of BRI and AIIB, it also becomes part of China's soft power program, and hence of Chinese attempts to cultivate a better picture of itself internationally as a state that stands against biased international organizations like World Bank and promotes development, and thus to address the China threat rhetoric.42 China is attempting to improve the BRI narrative by incorporating the concepts of "harmony and inclusion" and "promotion of people-to-people bonds" into the BRI objectives. These ideas are intended to strengthen China's soft power, as well as cultural exchange and cooperation among countries along the BRI path. China tends to prioritize economic cooperation and peaceful growth by downplaying the BRI's diplomatic and military impact.43 However, the “Chinese dream” is not just “peaceful development” and “win-win.” With international cooperation, on the one hand, BRI and AIIB provides a more authoritarian and more assertive Chinese approach to defending Chinese sovereignty and core interests. This is particularly evident in light of Xi's insistence on China's rejuvenation, which is portrayed as China regaining international status, privileges, and influence. Under Xi, China has become more optimistic in advancing China's own ideas about the growth of the international community and China's position in it, as well as in presenting its own political principles and programs, such as the BRI, and more proactively attempting to transform events and trends. The "Chinese Dream" is the perfect example to signify the acceptance of the “fen fa you wei” [striving for achievement] strategy and exemption from maintaining a low profile and instead to begin displaying and using skills and declaring or vying for leadership.44 In order to fulfill the "Chinese dream," China has to secure its core interest, which was first identified by the State Councilor Dai Bingguo officially in 2009 as (i) fundamental power structure and security of the state; (ii) state sovereignty and territorial integrity; and (iii) secure economic and societal growth. With Xi Jinping in power, these interests were expanded to include “peaceful development” and "national reunification" of territories currently occupied by the People's Republic of China and the Republic of China, potentially leading to the establishment of a formal union between the two republics. These interests were included to the list of China's core interests in the 2011 White Paper. Xi Jinping has brought these core interests to the forefront of China's foreign policy.45 China has made it clear that upholding its core interests is an integral part of win-win cooperation and has cautioned that foreign countries must respect China’s interest in order to achieve the benefits of their relation. Xi Jinping often employs this idea of mutual growth and “Chinese dream” in his speeches at international conferences, both within and outside of China.46 In 2017, Xi Jinping stated that: