What is a cyclical history? Why does humanity seem doomed to repeat the same mistakes over and over again? Are we doomed to this machine called fate? What is a soul, and how do I express it? Predicting what futures may lay ahead for humanity if we continue on some popular cultural paths, a body of twentieth century authors has created literary experiments designed to test the limits of human imagination. Nuclear warfare, artificial intelligence, inter-galactic travel, and the nature of spirituality itself all come woven together in the texts, which are profoundly affected by enlightened science, the competitive state of twentieth century politics and the eighteenth century German philosopher Georg Hegel.

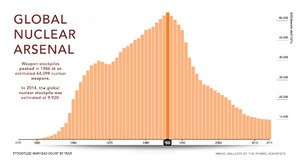

The concept of a detonating atomic bomb can be quite unassuming; the image itself can be found on coffee mugs, t-shirts, and has come to represent in popular culture a metaphor for when things get completely out of control, usually in a highly comic fashion. (Think of the little mushroom clouds that erupt from the top of Daffy Duck’s head when he is confounded by that pernicious Bronx tongued rabbit.) It is profligate in song and poetry: Inspectah Deck of the popular group Wu-Tang Clan colloquially touting his masterful ability to rhyme as “bombing atomically,” stretching the limits of nuclear discourse to describe his lyrical play and metaphorical dexterity. It represents the limits of destruction, and for many, the crowning scientific achievement of humanity

From within our little academic blast bunkers, the ubiquitous symbol of annihilation has the tendency to become a quaint point of discussion, a postcard from a historically and politically isolated reality. No matter how trivialized, the foreboding dome of toxic death elegantly rising upwards into the atmosphere, infusing the biosphere with vast quantities of radioactive poison, has to be taken as seriously as possible. When considering the natural (design or form) of the atom, it is one of cohesion and unity, a balance of huge unseen energies in the most compact of units. To destroy this article of matter is to rip apart the fabric of the cosmos and unleash sublime forces; that once unveiled cannot realistically be contained by any invention or intention of humanity. The science and related literature of atomic industry is as terrifying as it is beautiful.

Luckily, a dedicated and imaginative group of literary artists and philosophical masterminds have stopped to wonder what forces are at work in our current society that could enable the guaranteed destruction of all civilization on earth. Through essays and novels that record the future history of a civilization felled by self induced nuclear warfare, these reflective critics of society are able to thoughtfully examine not only the society in which we live, but also what it is about human nature that could possibly be compelled to recreate such devastating manifestations of technology and culture after the terminal blast.

It is easy to laugh at the conclusion of Stanley Kubrick’s timeless film Dr. Strangelove.[2] Indeed, by the time Major T.J. ‘King’ Kong is hooting excitedly while he rides the warhead into the heart of Asia, the audience should want the bombs to fall on the heads of the absorbed political animals scuttling among various secret government offices. While this film chronicles one of the many unique ways in which full scale nuclear war can come about the most curious scene in the film shows the heads of state trying to figure out how to endure once the biosphere of earth will be forever altered by the ominous isotope “Bal thorium G.” (Best if said aloud in a deep and menacing Soviet accent.) The dark comedic energy of this scene gains density as the Western protagonists assume that life on earth could be relatively the same following a world wide nuclear conflict. The last laugh of the film isn’t for them so much, as it is the chuckling relief that comes when the credits roll, the final lyrical melody ‘We’ll meet again/Don’t know where, Don’t know when…” foreshadowing that if civilization manages to survive the great war, there is a possibility that this slapstick drama of intercontinental destruction could receive a second billing.

There exists today a body of literature known as ‘post nuclear fiction’ that attempts to realistically address what kinds of issues will face humanity following a world wide nuclear conflict. Because these works of fiction tackle the entire history of our own culture through the lens of futuristic characters, the concept of history itself is invented as means to construct the plots of these novels. Frequently investigating how the adventitious survivors will rise again from the ashes, these authors investigate what roles language, recorded history, and the innate trait of rationality will play in the reconstitution of civilizations following a major world wide catastrophe. Unlike an asteroid the size of Manhattan plunging into the Hanford Site, Tokyo, or an earthquake tearing China in half, an intercontinental nuclear war has the facet of being human made. Whether or not the survivors in post nuclear fiction will rebuild to the point that a second round of nuclear warfare is the inevitable outcome is a chilling question that cannot be so easily swept from the table of possibilities. We laugh at the delusions of grandeur harbored by Dr. Strangelove and his silly compatriots even though little provision is made by him to accommodate a realistic and sustainable plan for civilization once it is razed by fire. “Mr. President,” hollers a general, “We cannot have a mineshaft gap!”

There are a few things that one must take into consideration when considering what it takes to build weapons of such awesome, god-like, power. First, the population of earth must reach such a critical mass that elaborate bodies of government are in place to manage the affairs and political machinations of humankind. Second, the great ongoing dialogue of science will have had to evolve to the point where computers and technology are available to safely control the fission of weaponized atoms. For the authors of many post-nuclear texts, even the usurpation of human skills by machines of varying intelligence signifies that technology probably plays a determining role in the every day cause and effect of culture and politics, and thus could enable war by gradually replacing our evolved instruments of rational decision.

These evolved instruments of the mind that suffer the possibility of being replaced by machines find their reflection in externalized ordered forms; thus religion, the humanist arts, and the concept of a structured code of morality in a divine universe are constantly featured as plot devices and character signifiers. Lastly, there exists around the margins of these two groups people, who under the guise of rationality, will seek to employ these weapons for political or social gain, not unlike Dr. Strangelove yelling “Mein Furher, I can walk!” as the bombs rain down, simultaneously paying homage to his master and personal interests. What happens next is already a give-in for authors of post-nuclear fiction, the beginning of these fictional worlds is the annihilation of our own.

Patricia Warrick explains how the discovery of nuclear technology not only raised the stakes of expression in post-nuclear fiction, but also redefined the responsibilities of artists to create the bomb as a cultural and epistemological focal point: “The explosion of the first atomic bombs in August of 1945, now recognized as a watershed date in man’s history, provoked a powerful literary response: an outpouring of holocaust and post holocaust literature dramatizing the realization that the world would never be the same. We came to understand we had been expelled from the garden of simplicity where we lived before the fall of the bomb” (Warrick, Cybernetic, 10). Viewers of Dr. Strangelove may chortle and guffaw at the zany antics of Peter Sellers’ title role of the hamstrung Dr. Strangelove, but the fusion of the coldly logical and calculating idealism of the politically allied nuclear physicist not only serves as an archetypical protagonist in many of the post nuclear texts, but also a major catalyst in creative process of post-nuclear writers. Allusions to Satan frequently accompany this brand of confidence peddlers. I want to focus on two texts that best represent the artistic possibilities of this provocative body of literature.

In both Walter Miller’s A Canticle for Leibowitz (1959) and Russell Hoban’s Riddley Walker (1980), two novels that elegantly sit atop a substantial body of post nuclear fiction, the intertwined fates of humanity, rationality, and technology are explored through the model of future histories. These novels most clearly articulate three fundamental questions thematically related to the three parameters of nuclear society listed above, questing to explore the nature of humanity and the fate of civilization.

The questions that these cyclical post nuclear fictions pose are best framed by evoking the Hegelian model of the dialectic. Hegel writes in Verstand[6] “Thus understood the Dialectical principle constitutes the life and soul of scientific progress, the dynamic which alone gives immanent connection and necessity to the body of science; and, in a word, is seen to constitute the real and the true, as opposed to the external, exaltation above the finite” (Hegel 95). What Hegel has captured in the lens of the dialectic is that once a concept can be handled rationally in the mind, the only due course of action will be name what it is, then proceed to deconstruct it into its constituent parts or even prove the opposite. Vice versa, the continuing dialectic is the process by which competitive or complimentary ideologies are synthesized in the rationally cultivated mind. These methods inform, sometimes unconsciously, the styles and quarries of the featured texts.

In Canticle, the entire history of the civilization on Earth that follows our own is tracked in three independent, but thematically united novellas, forming a neat trilogy of visions that span the course of an entire civilization. The first of these, “Fiat Homo,” chronicles the early stages of society following a nuclear war, when most people are illiterate and superstition is rampant, living in diseased hovels and caves like our own Western ancestors did as civilization steadily awakened from the Dark Ages. Albert Einstein once quipped that World War IV would be fought with sticks and stones, Miller allows civilization following World War III to grow a bit further than Einstein’s imaginative projection.

Beginning with a world plunged into a primitive state devoid of any government or technological sophistication, a band of Judeo-Christian monks in the desert of Utah, known as “bookleggers,” strives to keep a tiny flame of literacy and historical knowledge vital in a world that is darkly illiterate and culturally barbaric, patrolled by mythic monsters, ironically called “Fallouts,” and mutants alike (Miller Canticle 4). Brother Francis becomes the main protagonist of this moment in history while trying to build a shelter in order to survive a Lenten fast in the volatile desert. Prompted by a strange wanderer named Benjamin, who casually marks a stone with Hebrew runes, he accidentally uncovers a bomb shelter left over from our own time. Supposedly, the remains of a twentieth century engineer named Leibowitz are entombed within, and the discovery of this crypt and the texts within prompt the substantiation of the Abbey and the mission of the monks to preserve texts and literacy. Brother Francis must endure a hellish trial to authenticate the documents he has discovered, and he finds meaning in the illumination of preserved texts. The gears of civilization are already in motion, but the canonization of Leibowitz ensures the rediscovery of our technological legacy. The governing body of the Judeo-Christian church known as New Rome is astride one of the seedling nation states known as Texarkana, which fosters and represents the secular discourses of this history.

The second section of the triptych, “Fiat Lux,” tells the story of the cultural renaissance and popularization of mechanical comforts that precipitates a troubled discourse between the secular and religious ideologies of the novel. Thon Taddeo, a renowned Texarkanian scholar, is a comedic reflection of the European humanist scholars such as Galileo, Descartes, and Newton, who propelled our own culture forward in search of truth and technological innovation. He represents the scientific/political animal who lays the track for the modern nuclear nation, a humble yet enthusiastic model for Dr..Strangelove. An interesting character that will be further discussed is the Poet, who exists as a literary consciousness in the novel, and one of the few characters possessing both artistic and animalistic qualities as foil to the archetype of the rational scientist. In this moment in history, the monks at the abbey have managed to build an electric lamp by extrapolating data from the texts and documents they have preserved, ennobled by the legacy of Leibowitz. This astounds Thon Taddeo, who feels legitimate professional and personal insult to have been surpassed by the monks, who have been quietly working without political assistance for centuries. As a secondary plot, the seeds of the modern nation-state are allowed to bloom. The culture of warring factions competing for land and influence in the ravaged North American continent reflects the rise of the European nation state in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Thon Taddeo takes the copies of the “memorabilia” back to his society, reintroducing the revelations of Einstein, Oppenheimer, and Bohr unto the world.

The third and final installment in this trilogy of novellas is “Fiat Voluntas Tua,” wherein Miller envisions a world much like our own, where nuclear technology has been rediscovered, travel to the stars is possible, and humankind is in a perpetual state of warfare refereed by Orwellian bodies of government. Civilization has completed another full cycle, and the only possible refuge from the war torn planet is escape to an interstellar colony. The main protagonist of the third novella is Brother Joshua, who manages to escape Earth moments before the world’s governments recreate their own destruction. It is his duty to transport the preserved texts and history of earth to a struggling colony, far off in another galaxy. The few remaining survivors on earth act out a morality play about assisted suicide before they are consumed by atomic fire and the limits of Miller’s vision for humanity. It is widely considered to be a landmark of both popular and science fiction literature, scoring a Hugo Award in 1961, and a radio adaptation for National Public Radio in 1981.Continued on Next Page »

Asimov, Isaac, Martin H. Greenberg, and Patricia Warrick, Eds. Machines That Think: The Best Science Fiction Stories About Robots and Computers. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1984.

A comprehensive anthology of the short stories that specifically deal with the impact that technology and artificial intelligence has had on the development of Science Fiction in the twentieth century. Some of Miller’s short stories are reproduced, illustrating the profound affect that artificial intelligence had on the author, predicting for several of the most startling revelations to be found in Canticle. In particular, Miller’s short story “I made you” (1953) addresses the relationship between a man and a wayward machine possessing intelligence. Also featured as a companion text to Miller’s work is Harlan Ellison’s “I Have No Mouth, and I must Scream” (1967)

Bennet, Walker. “The Theme of Responsibility in Miller’s A Canticle for Leibowitz.” English Journal 51 (April 1970), [484-489]

A short article that examines the importance of morality and choice in Miller’s novel, and how that morality is manifest in both religious and secular characters in the course of the story. It does not address “choice” as a possible component of the “dialectic.”

Brians, Paul. Nuclear Holocausts: Atomic War in Fiction. Kent, Ohio: The Kent State University Press, 1987.

Brians maintains that Miller’s novel, among others produced in the nuclear age, is a direct action to philosophically address the implications of a nuclear catastrophe in modern culture. The importance of survival, as a historical necessity in prolonging human life following a nuclear catastrophe, adds a unique ecological perspective on the ‘arid irradiated desert’ in which Miller’s future history takes place.

Dowling, David. Fictions of Nuclear Disaster. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1987.

Dowling’s book is a survey of modern fiction concerned with nuclear weapons and the effect that such technology may have on the fate of humanity. He gives due credit to the concepts of the ‘cyclical’ history and artificial intelligence as players upon the modern nuclear stage. Most important is the chapter “Two Exemplary Fictions” in which Canticle and Riddley Walker are discussed as the capstones of the ‘post nuclear genre.’

Fried, Lewis. “A Canticle for Leibowitz: A Song for Benjamin.” Extrapolation 42, (Winter 2001) Kent State University Press, Ohio [362-373]

An astute treatment of Miller’s novel focusing primarily on the religious symbolism and the latent stereotypes of the Semitic characters present therein. Contextualizes Miller’s novel as morosely Christian, and only pays lip service to Riddley Walker as an interesting companion text.

Hegel, Georg. The Essential Writings Ed. by Frederick G. Weiss. New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1974

This is the best compilation in English of Hegel’s theories and methods. This is a crucial text for the understanding of Hegel’s role in the discourse of philosophy and the impact that he has had upon the philosophical community at large. Therein, the Phenomenology of the Spirit and Verstand are reproduced, detailing the philosophical constructs of the thesis, antithesis, and synthesis that make up the process of the historical dialectic. Also included is a treatise “With What Must Science Begin?” that takes into account rational and spiritual conventions as competing ideologies within historical dialectic of humanity.

Hoban, Russell. Riddley Walker 1980 Rpt. First Indiana University Press Ed. 1998

Herbert, Gary B. “The Hegelian ‘Bad Infinite’ in Walter Miller’s A Canticle for Leibowitz.” Extrapolation: 31 (Summer 1990), [160-169]

Herbert’s essay finds many examples of competing ideologies within Canticle that ‘define’ as much as they disdain one another in the process of the dialectic. Herbert’s focus is mostly on the possible negative results of the dialectic (‘Bad Infinite’) rather than on the examination of the dialectical process itself.

Manganello, Dominic. “History as Judgment and Promise in A Canticle for Leibowitz.” Science Fiction Studies 13 (1986), [159-169]

An excellent article that shows how Canticle can be considered a literal history of the future, and how over time a cultural memory has the ability to misappropriate symbols and skew historical dialogues. He illustrates how ‘logos’ is literally up for grabs when spread over several generations of thought and cultural revolution, citing Miller’s Thon Taddeo as the principal player in the historical process of Canticle.

Miller, Walter Jr. A Canticle for Leibowitz. 1959, Rpt. New York: Doubleday, 1997

Miller, Walter Jr. and Martin Greenberg Eds. Beyond Armageddon Copyright Walter

Miller and Martin Greenberg 1985 New York: Primus Press

A thrilling anthology of post-apocalyptic short stories edited and introduced by Walter Miller. Harlan Ellison’s “A Boy and His Dog” is featured and praised by Miller. In the introduction, Miller takes ample space explaining his disgust with the modern nuclear nation, how language barriers only exasperate political tension, and how art is an important diversion to hawkish politics.

Mullen, R.D. “Dialect, Grapholect, and Story: Russell Hoban’s Riddley Walker as Science Fiction.” Science Fiction Studies 27 (November 2000) [381-417]

An extensive exploration of “Riddleyspeak’ and the linguistic trends that unify the language employed in the novel. Also highlights contrasting points of view from other science fiction authors (notably Norman Spinrad who wrote an introduction to Canticle in one of its reprints) Extremely useful in decoding Riddleyspeak, as well as in showing how language is the signifying article of the ongoing historical process.

Mustazza, Leonard. “Myth and History in Russell Hoban’s Riddley Walker” Studies in

Contemporary Fiction 31 (Fall 1989), [17-26]

Mustazza expertly illustrates the importance of myth in its relation to history within cultures that are primarily oral in the transmission of cultural information, specifically citing Mircea Eliade’s construction of myth. Mustazza also shows how Riddley’s creation of his own identity through the act of writing, and his decoding of the Eusa myth, illustrates a metamorphosis from an oral culture to a text based culture.

Percy, Walker. “Walker Percy on Walter M Miller Jr’s A Canticle for Leibowitz.” Rediscoveries, ed. David Madden. New York: Crown, 1971, [262-269]

Percy explores the nature of symbols and the importance that they have to the development of Miller’s plot. Also illustrates that because Miller’s novel is a collection of symbols and themes (a novel per se), the text becomes self reflexive with the knowledge that all texts and symbols are transient and open to interpretation.

Porter, Jeffrey. “‘Three Quarks for Muster Mark:’ Quantum Wordplay and Nuclear Discourse in Russell Hoban’s Riddley Walker.” Contemporary Literature 31 1990 [448-69]

Porter contextualizes the importance of nuclear technology and atomic theory within Hoban’s novel and modern examples of literature at large. Also, he keenly illustrates how ‘dialect’ (not the Hegelian dialectic) is a natural process by which language evolves through the development of ‘anti-languages.’ Also, shows how the preservation of texts and the evolution of language in history thematically unite Miller and Hoban as artists.

Rank, Hugh. “Song out of Season: A Canticle for Leibowitz.” Renascence 21 Summer 1969 [313-321]

One of the earliest critical evaluations of Miller’s novel; explaining the importance and groundbreaking nature of Miller’s work, identifying cyclical themes, the importance of a historical consciousness, and the comedic nature of the monks who toil in service to their Christian idealism.

Seed, David. “H.G. Wells and the Liberating Atom” Science Fiction Studies 30 (March, 2003), [33-48]

Along with Warrick’s historical analysis, this article best situates any reader of texts that deal specifically with nuclear weaponry and its associated catastrophes. Specifically outlines how much of the fiction produced after World War II that deals with nuclear war is constructed in the form of ‘future histories.’ Seed outlines the philosophical implications that arise from man’s ability to master the atom, and the effect that this power has had on twentieth century thought, citing many examples in contemporary science fiction.

Seed, David. “Recycling Texts of the Culture: Walter M. Miller’s A Canticle for Leibowitz.” Extrapolation 37 (Fall 1996), [257-271]

This article best articulates the roles that texts and language play in the context of Miller’s novel, by showing that without the ‘memorabilia’ the course of history for this futuristic world would have been very different. Also includes a thorough examination of short stories by Miller (“Dumb Waiter,” among others) that illustrate the popular and recurrent themes of his work: the future of humanity, the soul, and the technology that enables the future and the presence of history.

Senior, W.A. “From Begetting of Monsters: Distortion as Unifier in A Canticle for Leibowitz.” Extrapolation 34 (1993) [329-339]

An excellent article that illustrates the innate tension and ‘distortion’ that arises out of dialogue and linguistic exchange. Most importantly, Senior finds many examples of how misappropriated symbols can have disastrous effects when employed out of context, such as Benjamin’s strange glyphs on the arch-stone and Thon Taddeo’s disgust with his inability to fully decode some of the memorabilia.

Spector, Judith A. “Walter Miller’s “A Canticle for Leibowitz:”A parable of our time?” Midwest Quarterly 22 (1981), [337-345]

A short article that examines how stories set in the future can be used as parodies of our own times. Specifically addresses the folly of nuclear armaments in general, and how Miller’s novel unabashedly attacks the culturally embedded arguments in man’s soul that leads to the development of nuclear weapons.

Sontag, Susan. “The Imagination of Disaster” in Against Interpretation. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux 1966.

A very useful article when reading any work in which world wide destruction is the subject matter. Contextualizes the profound impact that violence can have upon artists and the communities in which they live and work. Although not quoted directly, this book is an essential resource for understanding many of the literary methods utilized in describing massive deaths and catastrophic destruction.

Stapledon, Olaf. Last and First Men 1930 Rpt. Dover Publications 2008

Stapledon, Olaf. Philosophy and Living, Vol. 2. London: Penguin, 1939 [304-307]

Explicitly illustrates the importance of the Hegelian dialectic to not only Stapledon as an author and philosopher, but also to writers of cyclical histories in general, as it is widely considered that Stapledon was immensely influential on the entire canon of Science Fiction in the twentieth century. This book serves as the crucial hinge between Hegel’s philosophy of history and the literary experiments in cyclical dialectic histories undertaken by Hoban and Miller.

Wagar, Warren W. Terminal Visions: The Literature of Last Things. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1982.

Wagar’s book is an insightful study that contextualizes and explains many of the popular conventions of apocalyptic literature.

Warrick, Patricia S. The Cybernetic Imagination in Science Fiction 1974 Rpt. Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, Cambridge MA 1980

Aside from Hegel and Stapledon, Warrick’s book is probably the most important critical work for illustrating the historical relevance of nuclear technology, the impact that artificial intelligence has had on the Science Fiction community, and accurately predicting many of the themes and literary constructions found in both Canticle and Riddley Walker; even though neither of the two novels receive mention in the work.

Endnotes

1.) Inspectah Deck is the nom de plume of Staten Island’s Jason Hunter. His lyrical content on the song “Triumph,” which addresses the importance of song in apocalyptic times, has helped to propel the album Wu-Tang Forever (RCA/Loud 1997) to the highest realms of contemporary cultural status, selling over half a million copies in its first week of release.

2.) Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Atomic Bomb (1964 Columbia Pictures), based on the novel Red Alert by Peter George, is widely considered to be one of the darkest satirical reflections of Cold War politics and warfare.

3.) The largest storehouse of radioactive waste in the terrestrial western hemisphere: Hanford, Washington.

4.) Hegel and nearly the entire canon of Western philosophy universally define this as the ability to make rational decisions based on empirically/phenomenologically derived data from the mind/senses. When something as catastrophic as the total extinction can be made with a “rational decision,” this faculty of the mind has come under attack by artists, scientists and those associated with politics and religion fervently since the dawn of atomic warfare in the twentieth century.

5.) Georg Hegel (1770-1831) was a German philosopher who was profoundly affected by the French Revolution and the extraordinary figure of Napoleon. His major work The Phenomenology of the Spirit (1807)established him as one of the most important philosophers of the European enlightenment. Therein, the concept and method of the dialectic was originated, outlining the concepts of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis as the basic modes in which competing historical ideologies assumed mastery over one another through the processes of social and political discourse.

6.) “Understanding” A corollary section of Hegel’s Phenomenology of the Spirit, in which the basic tenets of the historical dialectic are imagined and discussed: the apprehension of concepts and the naming thereof as the first crucial step in the process of forming dialectical ideologies that will ultimately be subverted or consumed in the course of history. Hegel and Miller both allude to the story of Genesis, where the serpent promises the knowledge to differentiate between “good” and “evil” to Eve and society.

7.) “Short lyrical song or melody”

8.) The year in which “Fiat Homo” occurs is supposedly the “Year of Our Lord 3174,” which would be the approximate equivalent of our own 1215, the immanence of nuclear war provoking Miller to subtract the 1959 years of civilization that had passed since the first beginning of Western.society. The Year 1215 is a watershed year in Western civilization, not just for the historical artifacts such as Magna Carta, but also what it represents to Miller as a reflection of human history: a time when the Roman Catholic Church was beginning to establish itself, when war, disease and superstition are rampant, and the first lights of the modern rational mind are beginning to twinkle in the arts, sciences and humanities for the first time in the West since the fall of the Roman empire. For Miller, this is where Canticle really begins.

9.) Through the rediscovery and innovation upon the classical humanist arts of Rome and Greece, these three luminaries established the enlightened Western mind and scientific discourses which enabled the development of modern civilization.

10.) Three of the most distinguished atomic scientists of the modern nuclear age, whose united work and distinguished research created the first atomic bombs sewn into the political and social fabric of history. Texts bearing their names, among other scientists, are discovered by Thon Taddeo while rifling through the library of preserved pre-holocaust texts.

11.) See R.D. Mullen’s article “Dialect, Grapholect…” for a comprehensive analysis of “Riddleyspeak.”

12.) Riddleyspeak: “connexion man” (Hoban 53).

13.) Not only is the theatre box one of the oldest forms of entertainment in Western culture, the characters of Punch and Judy show are one of the few puppet shows that have attained celebrity status through centuries of performance in both Europe and America. See Illustration 1 “Punch” (Doherty 2009).

14.) Riddleyspeak: “some poasyum” (Hoban Glossary)

15.) Apart: Sex is moot point in both novels, as Riddley is twelve years old, and the cloistered halls of Leibowitz do not feature any women as protagonist characters. When mentioned at all, conjugation is only featured as a passing reference to motherhood or as a functional component of survival.

16.) The reason for Benjamin’s longevity is never fully revealed by Miller, but Lewis Fried contends that Benjamin is a reflection of the archetypical wandering Jew, commonly found in many thematically religious texts that deal with the Diaspora and its related literature. The Poet muses in “Fiat Lux” that perhaps the consumption of an irradiated blue headed goat’s milk is the secret to eternal life.

17.) Heat Death: An era in the projected history of the universe in which all of the stored fuels and energies found in stars, and other natural phenomenon of the cosmos, achieve equilibrium and no kinetic forces are at work to continue the expansion and modulation of space. The essential feature of Hegelian synthesis is reaching an equilibrium or compromise among competing forces or ideologies.

18.) Lat. “Thinking Machine”

19.) “Sulfur,” which is known as “yellow stoans” in the world of Riddley Walker is the volatile element which has a sickly yellow pallor and scent, is one of the three essential ingredients of gunpowder. The “1 Big 1” or “atom bomb,” is the abstract goal of he characters in Riddley Walker that seek power. (Hoban, Riddley Walker, included glossary in Kent State Edition.)

20.) “Fiat Voluntas Tua”

21.) The mysterious hypothetical origin of the universe, in which all of the matter found in the cosmos was suddenly created and sown outwards into space-time.

22.) See Illustration 2 “The Arch of Brother Francis” Doherty 2009

23.) “Dog Eat Dog”

24.) The Terminator, (1984 Orion Pictures), Terminator II: Judgment Day (1991 Metro-Goldwyn Mayer), and Terminator III: Rise of the Machines (2003 Warner Bros.)Dir. James Cameron, Jonathon Mostow

25.) The Watchmen (2009 Fox/Warner Brothers Pictures and Distribution) directed by Zack Snyder, based on the original graphic novel The Watchmen by Alan Moore and David Gibbons, DC Comics 1987

26.) Jemaine Clement and Bret McKenzie, “The Humans are Dead,” featured on The Flight of the Conchords’ The Distant Future (Sub Pop 2007) Best viewed at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WGoi1MSGu64