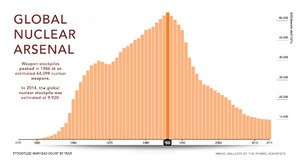

Future Hell: Nuclear Fiction in Pursuit of HistoryVI. Broader Implications of the Two StoriesBoth the monks of Leibowitz and Riddley Walker seem ultimately forgiving of those that simply wish to discover and learn about the nature of the universe. The monks welcome anyone who wishes to study at the abbey in pursuit of greater truth or enlightenment, but fight against the dissolution of human life until the conclusion of the novel. Under the symbols of Judeo-Christian culture, they labor thanklessly through history in service to humanity, only to be consumed by the same fire that had once visited the earth. Hugh Rank is quick to point out that Miller can’t help but find the comedic elements in this senseless repetition of flawed judgment. When the ancient abbey (and much of the world for that matter) is reduced to rubble at the conclusion of Canticle, and Brother Joshua is hurtling towards an unknown fate in the cosmos, the division of the church and its related symbols creates a dramatic metaphor by which Miller can express his disgust for the aspects of humanity that would enable a nuclear war. The image of the shattered crucifix best represents the world in which Riddley inhabits: where civilization, history, language, and matter itself have been torn apart (via nuclear weaponry) and the survivors are left to reassemble the pieces. His projections of peaceful future through the alternate Punch and Judy show is his attempt to route the future of humanity away from re-shattering the crucifix. Both the Punch and Judy show and the Judeo-Christian ideologies represent the thematic foils to scientific culture. It is the rationality of science that invites humanity to peel away the layers of nature to reveal the unseen forces that motivate the universe. Both Hoban and Miller could see that this drive to break apart something as simple as the atom could only have disastrous consequences. Crucially, when weighing the development of the civilized mind over the span of history, these authors find that when not critically investigating the secrets of nature, the only other diversion for humanity is the arts,15 which can also pry apart nature, but with considerably less dangerous consequences. This critique of rationality is the most poignant statement that many works of post nuclear fiction can make, because novels that utilize alternate histories to critically examine our culture take into account that the deployment of a nuclear arsenal is often done with the rational logic that defines the absurdly comic, yet manic survivalism of Dr. Strangelove. Dominic Manganello points out that this view of human nature is central to understanding the competing factions across Miller’s history, and that it is Thon Taddeo who represents the synthesis of brains and ambition clashing against the humility and crafts of the monks. Thon Taddeo is in the unique position to use his knowledge of history to affect the future of humanity, but is not reflexive to realize that his discoveries ensure a future marked by the flames and flashes of nuclear war.Even though they differ stylistically, the reflexive characters present in both stories work tirelessly to decipher an encrypted history from a civilization they know has passed. To say that one is reflexive in the context of the Hegelian philosophy and nuclear fiction means that the reader or character must possess knowledge of the larger dialectic in which they participate. In both novels, reading is fundamental as a precursor to modern civilization, but the absence of a contextualizing culture that would have been built around the memorabilia in Canticle, and the fact that the Eusa play has been programmed as a children’s play in Riddley Walker illustrates how much these characters must struggle with the interpretation of their own historical legacies. That Riddley Walker is a personal journal by the title character, in which Riddley reveals knowledge that his actions will determine the course of history, imbues him with a historical consciousness and the power of will to use the knowledge of history to his benefit. Whereas Miller is a determinist about the fate of civilization, his novel depicting the rediscovery and employment of nuclear technology as a weapon, Hoban holds out hope that Riddley’s invention of a new Punch and Judy show (literally a new historical and cultural dialogue) will be the antithetical dialogue to the Eusa show: which for Riddley, only holds the promise of death. For Miller, the philosophical tenets of the Christian church represent the antithesis to the calculating secular forces manifest in Thon Taddeo, making a satirical reflection of the competition between the scientific and religious ideologies over the course of history. Each of these novels, possessing dialectical structures, demanded of the artists unique forms in which to be expressed. This crucial difference in perspective is best manifest in the way in which each novel is narrated. In Canticle, Miller employs an omniscient perspective to tell the story of this entire civilization, demonstrating that the inevitable cycles of history are propelled by innately destructive characters in historical competition with innately peaceful characters. The model of the morality play, as the classic arena in which these truths are tested, is frequently toyed with by Miller. On the other hand, Hoban offers more hope for the future of humanity, telling the story of Riddley Walker through the first person narrative of the title character. Not only does Riddley invent himself through language, the reader also has direct access into the mind of a person who can foresee the corrupting influences of secular science coupled with political ambition. The fact that Riddley makes it known that his journal is written after all of these events have transpired illustrates to the reader that this character is sensitive to the concept of history and the importance of this journal as a historical artifact. When Riddley explicitly says “May be a nother 100 years and kids will sing a rime of Riddley Walker and Abel Goodparley with ther circle game,” this is a self.reflexive act of consciousness and proof that he is aware of a larger scheme at play in the universe, and that possibly the journal of his adventures will someday be as common as the Eusa play (Hoban 115). When Riddley casually remarks “Iwl write it down here,” at several points in the story, he is actively pursuing not just his own literacy for the sake of reading and writing, he is hoping that his work will enter the recorded dialectic and have a positive impact upon the future. Note that in the alien context of Riddleyspeak, the part of speech: “write it down here” has endured relatively intact, its concreteness and familiarity suggesting severe relevance to the reader (Hoban 81). The monks and several characters in Canticle have flashing moments of this reflexive consciousness, but are drowned out by the deafening march of civilization all around them. The reflexive character of Benjamin, the mysterious Hebrew speaking hermit who is the only character consistently present in each stage of Miller’s future history, serves as the only character who really knows the full history of the human race, believing the coming of the messiah is the only thing that could derail the march of cultural progress. When the ragged, loincloth bedraggled hermit confronts the scientific protagonist Thon Taddeo at the conclusion of “Fiat Lux,” by demanding to know “Are you Him?” he is wondering if Thon Taddeo is the one who can truly redeem the human race from the endless dialectic cycles of cultural growth and near extinction (Miller, Canticle 216). The one moment in Miller’s novel when a non-supernatural16 character possesses reflexive knowledge about History is when an Abbot in “Fiat Lux” muses to himself that Thon Taddeo can only rediscover the technology that he has been toiling to discover. “He’s finding out that some of his discoveries are only rediscoveries, and it leaves a bitter taste” (Miller, Canticle 209). VII. Contextualizing Miller and Hoban in Hegel and Other LiteratureBoth novels are generally accepted as being ‘cyclical’ in nature, in that humanity will surge and recede along cycles of growth and decline. David Seed, in his “Recycling the Texts of the Culture,” describes Miller’s method of cyclical history in determinist terms: “The grimmest implication of repetition in the novel is the suggestion that history consists of a cyclical script determining human behavior from era to era” (Seed Extrapolation 269). It strikes me that both Miller and Hoban had at least created the hope that their heroes would find a.way to escape these endless cycles of history. In Miller’s text, the competing discourses of the positive religious and negatively secular embody the historical evolution of this civilization, while in Riddley Walker; Riddley is an activist against the rise of politically malicious power. Each new cycle of civilization in Miller and Hoban’s visions starts from the beginning with a terrible nuclear flash, the essential feature of post-nuclear fiction and realistically the only power within humankind’s reach of wiping the slate of civilization clean in one fell swoop. The first Hegelian question (of the three mentioned in section II) addresses the faculties of human rationality, and whether this unique ability simultaneously raises man out of the primordial forests, but also dooms him to his own termination. The second explores the transitory nature of language, and how the false sense of power that arises from ‘naming’ only puts a wedge between exterior reality and the interior psychological dialogues of humanity. The narrator of “Fiat Voluntas Tua” says that “To communicate a fact always seemed to lend it fuller existence,” implying that once information is encoded into language, it assumes a denser meaning in the public sphere, and it is the dual quality of language to obscure as much as it may clarify that incenses Miller (Miller Canticle 260). Naming and words in general are symbols of power to both authors, who understand that how we understand history is through language and organized methods of historical knowledge. The third question tackles the complexity of cyclical history, and whether through the union of rational innovation and language systems, the cultural consciousness of humanity could hypothetically extend forever. This third question has an ancillary inquiry, because one of the tenets of the Hegelian dialectic is that so long as there is an ongoing clash of values, the minds that entertain them will be present to prolong them. The concept of man being permanently doomed to recycle his own annihilation so long as the cultural consciousness of humanity remains vital is a haunting theme familiar to writers of cyclical histories. Olaf Stapledon penned the first major cyclical novel of the future, Last and First Men (1930),wherein the future history of human consciousness is extended over billions of years, waxing and waning along cycles of growth and technological evolution. He acknowledged in another work, Philosophy and Living, the debt that fiction authors of cyclical histories owe to the 18th century German philosopher Georg Hegel: “For the understanding of history, then, we must detect in the culture of a people at a given time the conditions in virtue of which that culture must presently be thrown into logical conflict with itself; and we must watch this conflict give birth to a new form of culture in which the conflict is resolved in a new synthesis…” (Stapledon 305). In Last and First Men, the first overhaul of history comes in the form of nuclear war on earth, the survivors in a Darwinian fashion reestablishing civilization and then spreading outward into the cosmos as new biological and technological adaptations enable the outward growth of humanity into the cosmos. The key word in this passage is synthesis, the terminal action of the historical dialectic: when all of the competing ideological discourses over history have been swallowed up by one another and the process begins again. It is a pre-atomic era form of the concept of heat death.17 Stapledon aptly summarizes the dialectic in Philosophy and Living as: “The condition of culture at any time, he says, contains within itself contradictions; and as the contradictory elements grow in strength the spirit suffers internal conflict, until at last a new condition emerges in which both the conflicting components are transformed and harmonized” (Stapledon Philosophy 305). For Hegel, synthesis is the soul of the dialectic, and this melding of values, prejudices, or competitive bodies over time constitutes the inevitable march of culture and history. Themes of fusion and unification constantly signify the attitudes of the peaceful characters: being at one with God’s will is the ultimate achievement for the monks, and the unity of the rebuilt image of the crucifix is the metaphorical goal of Riddley Walker. Synthesis is a fundamental concept for serious artists working within the larger science fiction genre, as reflections of it can be found in many biological, technological, historically investigative texts. One of the most nightmarish meditations upon the concept of synthesis by an author frequently associated with Miller, as a paradigm of technologically savvy cyclical science fiction, is Harlan Ellison. His 1967 story “I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream,” (Asimov Machines 233) imagines a human being trapped within the bowels of an evil and manipulative machina analytica[18], the two eventually coming to exist in a horrifying symbiosis, and a psychologically co-dependent relationship. The Hegelian force is strong in these artists. Hegel lived long before the discovery of atomic energy, but his concept of the synthesis accurately predicts for the historical sea change that nuclear conflict promises. In their novels, both Hoban and Miller have assumed that all the political, social, and cultural threads of our own civilization have synthesized in the process of the dialectic, resulting in a nuclear holocaust. Historically speaking, whoever has the largest sword is able to write history, and since the stakes have been raised to that of nuclear annihilation, the final synthesis of all history is fused with one great intercontinental exchange of atomic warheads. Hence, both authors are critical of man’s reliance on applied technology as a political game piece. The influence of high speed computers in the twentieth century on the philosophy of logic, technology supposedly refining rational processes, apparently enables political systems which can build and execute a nuclear holocaust. Both Hoban and Miller are living and writing in the age of automated warfare, a common point of interest in nuclear fiction, possibly best dramatized by Mordecai Roshwald’s 1959 novel Level 7, wherein a subterranean community of soldiers, selected for the ability to follow orders, is ordered to create the apocalypse in the event that their superiors on the surface are destroyed. The parable of humanity striving to be like a machine informs these texts, signifying that only bad can come from the union of the human and machine. The theme of humanity as a perfectly rational creature.acting literally like a computer is lampooned, but the idea of a post-nuclear society is not explicitly explored in the context of short novel.What unites this novel with the work of Hoban and Miller is the supposed belief that the rationalization of civilian casualties in the event of a nuclear war creates an absurdist view of technology and a pointed criticism of humanity’s false reliance upon his machines to endure. For Miller, writes Gary Herbert, if nuclear war cannot change the nature of humanity, nothing will (Herbert 165). Hegel’s legacy for twentieth century writers of science fiction is not just the concept of the dialectic; it is also his warnings about the intertwining of humanity and the treachery of rationality. Hegel proposes that while science is a practical development and unique conduit of reason, it can discover and unleash forces that can consume even itself: “The essential requirement for the science of logic is not so much that the beginning be a pure immediacy, but rather that the whole of the science be within itself a circle in which the first is also the last and the last is also the first” (Hegel “With What Must Science Begin?”106). In other words, technology is the cause of and solution to all of humanity’s problems, and Miller and Hoban create their stories as meditations upon this familiar axiom of logic. For Hegel, Stapledon, Miller and Hoban (listed respectively in order of their appearance on the cultural scene) the dialectical synthesis can only result in a complete cyclical overhaul of civilization. Stapledon, who was a philosopher as well as a popular fiction author, created a future history that bears the obvious rigor of the Hegelian influence; the expository history of Last and First Men is distinctly different from the character-based narratives of Canticle and Riddley Walker. What sets Hoban and Miller apart from Stapledon and from one another philosophically is how much faith each author has in their subjects to recreate a world of peace and cultural prosperity given humanity’s dual propensity for science and the formation of competitive nation- states. Miller ends the history of his future world with the notion that the only life on earth following the second terminal war will be a few buzzards, sharks, and stray deformed mutants, the last shred of humanity hurtling in a starship towards an unknown fate in the deep reaches of space. Hoban is more hopeful, not promising a cultural overhaul per se, but still leaving the option open if people like Riddley cannot thrive in this new world to compete against the evil ideologies that exist in characters like Goodparley and Orfing. Because these novels are contextualized as future histories, the important concept that mirrors the possibility of an unbroken dialectic is that it could be possible for the consciousness of humanity to have unlimited run in the cosmos.Continued on Next Page » Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in Literature |