|

From Cornell International Affairs Review VOL. 10 NO. 1 Quantifying China's Influence on the Shanghai Cooperation Organization

By Abigail Grace

Cornell International Affairs Review

2016, Vol. 10 No. 1 | pg. 2/3 | « »

While the Western scholars discussed above have identified the SCO as an instrument of Chinese foreign policy, China-based academicians and the CCP have denounced this viewpoint. Little has been done to quantify Westerns scholars' assertions and draw comparative conclusions between China's involvement in the SCO and its involvement in other regional multilateral organizations. Therefore, in an effort to provide more robust and conclusive evidence supporting Wu and Lansdowne, Gill, Wuthnow et al, and Chung's claims that China influences the policy of the SCO, this study takes a quantitative approach to understanding China's influence on the SCO's policies and objectives. A frequency analysis of ten "key phrases" reappearing within China's National Defense White Papers will be conducted on four key SCO documents. In an effort to compare the PRC's influence on the SCO versus other regional multilateral security organizations, three ASEAN+1 documents will also be examined for the frequency of these phrases. When regional multilateral organizations, such as ASEAN+1 and the SCO choose to employ one of these ten phrases, they are accepting the connotations associated with the phrase. The acceptance of the phrase's connotations also can be viewed as an implicit endorsement of related PRC policy. After results from the frequency analysis are obtained, this study will examine which phrases have the highest occurrences in SCO documents and ASEAN+1 documents.

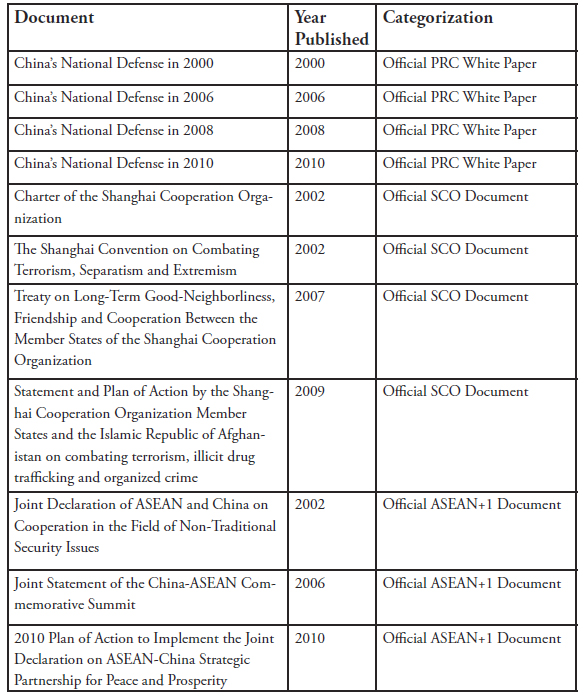

These ten "key phrases" were not selected at random. All phrases are explicitly tied to the list of previously identified Chinese regional security objectives. As evidenced in the data shown in Figure 2, these phrases appear at extremely high rates in foundational Chinese governance documents. Their high-levels of repetition across decades of official defense policy documents demonstrates that policymakers within China deem them to be unique and critical to Chinese interests. Furthermore, this study's methodology is grounded in the premise that the inclusion of a particular policy-oriented phrase does not just reflect the adoption of the PRC's policy, but also whatever connotations are associated with the phrase. The below chart lists all phrases that this analysis will search for, their English translations, and the connotations associated with the phrase. Connotations associated with the below phrases were derived from a review of these phrases usage within China's National Defense White Papers issued from 2000-present.28 Eleven documents indicative of the PRC, SCO, and ASEAN's positions on regional security issues were selected for analysis. These documents are grouped into three over-arching categories: China's National Defense White Papers, a biennial publication documenting China's military and defense priorities; Shanghai Cooperation Organization statements and treaties; and ASEAN+1 treaties and statements. All selected documents have a general emphasis on regional defense and security cooperation. Examined documents were either originally published in Mandarin, or a translation in Mandarin was produced concurrently with the treaties' signing. A complete listing of documents, their respective publication dates, and their associated categorization is located in Appendix One.

Skeptics of this approach could argue that these terms, such as peace (和 平, heping) mutual trust (互信, huxin), and struggle (挑战, tiaozhan) could be as highly valued by other member states as they are by the PRC. However, the concluding qualitative portion of this review seeks to demonstrate why these ten phrases carry an outsized influence for the Chinese government. Therefore, the final component of this study will put these findings in conversation with the examined document as a whole. What objective was the identified phrase advancing within the treaty or statement? How does this priority correlate to the PRC's key regional security objectives? Does the occurrence of this word lend credence to the overall argument that the PRC is shaping the policies and priorities of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization? While the frequency of these phrases demonstrates that Chinese interlocutors are able to exert discursive influence on treaties issued by the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, qualitative analysis shows the policy implications of these phrases generates significant gains for Chinese government positions on contested issues. Conversely, the absence of these phrases in ASEAN+ 1 documents alludes that, though China might seek to influence ASEAN and its member states, ASEAN's relatively robust institutional framework does not enable China to substantively alter member states positions on controversial security issues.

Figure 1: Selected Phrases, Their Translations, and Their Connotations

The below findings overwhelmingly support the hypothesis that key foreign policy phrases used by the PRC within their own domestic documents occur at dramatically higher rates in SCO documents than in ASEAN+1 documents. Each key phrase identified within China's National Defense White Papers occurred within at least one, if not all, of the three selected SCO documents. The same did not hold for ASEAN+1 documents. Phrases that are notably omitted from all ASEAN+1 documents include mutual respect (互尊, huzun), separatism (分裂主 义, fenlie zhuyi), extremism (极端主义, jiduan zhuyi), and threat (威胁, weixie). The phrase good neighbor (睦邻 , mulin) only makes one appearance throughout examined ASEAN+1 documents. This stands in stark contrast to SCO documents, which, when taking into account the vast differences in length between China's National Defense White Papers and SCO documents examined, had similar usage rates for most key phrases. The below table lists key phrases' rate of appearance within each of the eleven selected documents.

Figure 2: Key Phrases Frequency Within Selected Documents

The preceding table demonstrates that phrases of political importance to the PRC appear at dramatically higher rates in SCO documents than in ASEAN+1 documents. The above findings' impact is made even clearer when looking at which key phrases appear within SCO and ASEAN+1 documents. The below chart indicates that SCO documents contain key phrases that span the entire spectrum of regional security objectives. SCO documents discuss common threats and struggles. The signing parties frequently invoke language on their mutual respect and trust for one another. Quite notably, the SCO documents include numerous references to combatting separatism (分裂主义, fenlie zhuyi) and extremism (极端主义, jiduan zhuyi). Inclusion of these phrases indicates adherence to the belief that China is facing serious challenges to its sovereignty in Taiwan, Xinjiang, and Tibet—a contentious position in the international sphere. In the selection of SCO documents, parties also included references to harmony (和谐, hexie), previously identified as a term that can harken back to Confucian conceptions of the world order. Overwhelmingly, SCO states affirm their commitment to be a good neighbor (睦 邻, mulin) to one another.

Notably, the key phrase most frequently reappearing in ASEAN+1 documents is peace (和平, heping). This phrase is most closely associated with the PRC's desire to retain regional stability within Asia. Undeniably, this is one of China and ASEAN's largest shared priorities. A primary objective of ASEAN is to support peace within Asia.29 Regional turmoil, such as a violent escalation of territorial disputes within South China Sea, would present large costs to both China and ASEAN. Their collective cooperation on this issue only stands to benefit both actors. Thus, the recurrence of peace (和平, heping) should not be read entirely as ASEAN submitting to Chinese policy objectives and priorities. Rather, it should indicate that both actors recognize that their strongest collective interest is peace. Accordingly, references to maintaining regional piece within Asia are quite prevalent throughout ASEAN's treaties and documents.

Figure 3: Frequency of Key Phrases in SCO & ASEAN+1 Documents

Figure 4 provides interesting insight on the relative frequency of key phrase utilization between selected SCO documents and China's National Defense White Papers. The first two selected SCO documents, "The Shanghai Convention on Combating Terrorism, Separatism and Extremism" and "Statement by the Shanghai Cooperation Organization Member States and the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan on combating terrorism, illicit drug trafficking and organized crime," predictably have much higher utilization of phrases characteristically used within strictly military and counter-terrorism contexts: terrorism (恐怖主义, kongbu zhuyi) and threat (威胁, weixie). However, both the "Charter of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization" and the "Treaty on Long-Term Good-Neighborliness, Friendship and Cooperation Between the Member States of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization" have similar usage rates of phrases such as peace (和平, heping) harmony (和谐, hexie), mutual trust (互信, huxin), struggle (挑战, tiaozhan), and threat (威胁, weixie). These phrases are connected with Chinese regional security objectives as diverse as maintaining regional stability within Asia, championing the "Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence," and the PRC's quest to obtain the status of "regional hegemon."

The quantitative evidence provided not only demonstrates that "key phrases" appear more frequently within SCO documents than in ASEAN+1 documents, but further analysis also indicates that the phrases that do appear within ASEAN+1 documents are not solely Chinese foreign policy objectives. Rather, ASEAN+1 documents emphasize key phrases that advance the objectives of both actors, while SCO documents relative frequency of key phrases closely mirrors key elements of many China's National Defense White Papers.

Figure 4: Relative Frequency of Key Phrases in SCO Documents and China's National Defense White PapersContinued on Next Page »

"Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)." Nuclear Threat Initiative. October 21, 2015. Accessed March 13, 2016.

Association of Southeast Asian Nations. 2010 Plan of Action to Implement the Joint Declaration on ASEAN-China Strategic Partnership for Peace and Prosperity. 2010.

Association of Southeast Asian Nations. ASEAN Community 2016 Fact Sheet. Jakarta, Indonesia. 2016.

Association of Southeast Asian Nations. Joint Declaration of ASEAN and China on Cooperation in the Field of Non-Traditional Security Issues. 2002.

Association of Southeast Asian Nations. Joint Statement of the China-ASEAN Commemorative Summit. 2006.

Amnesty International. China: Gross Violations of Human Rights in the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region. Publication. 018th ed. Vol. 17. London: Amnesty International, 1999, 10.

Amnesty International. People's Republic of China China's Anti-Terrorism Legislation and Repression in the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region. Publication. 010th ed. Vol. 17. London: Amnesty International, 2002.

Ba, Alice D. "China and ASEAN: Renavigating Relations for a 21st-century Asia." Asian Survey 43, no. 4 (July/August 2003): 622-47.

Baer, George W. One Hundred Years of Sea Power: The U.S. Navy, 1890-1990. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1994.

"Beijing Inflicts a Defeat on Al-Qaeda." South China Morning Post, January 25, 2007.

Campbell, Caitlin, U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission. "Highlights from China's New Defense White Paper, ‘China's Military Strategy.'" Washington, DC. 2015.

"Chinese FM Calls for United Front to Fight Terrorism." Xinhua. November 15, 2015. Accessed February 06, 2016.

Chung, Chien-Peng. "The Shanghai Co-operation Organization: China's Changing Influence in Central Asia." The China Quarterly, 2004, 989-1009.

FIDH—International Federation for Human Rights, Antonie Bernand, Michelle Kissenkoetter, David Knaute, and Vanessa Rizk, The Shanghai Cooperation Organization: A Vehicle for Human Rights Violations. Paris, France, August 2012).

Gill, Bates. "China's New Security Multilateralism and Its Implications for the Asia–Pacific Region." In SIPRI Yearbook 2004, 210. Stockholm: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, 2004.

Katsumata, Hiro. ASEAN's Cooperative Security Enterprise: Norms and Interests in the ASEAN Regional Forum. (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009).

Kent, Ann. "China's International Socialization: The Role of International Organizations." Global Governance 8, no. 3 (2002): 343-64.

Rozman, Gilbert. "Invocations of Chinese Traditions in International Relations." Journal of Chinese Political Science, 17, no. 1, (2012): 111-24.

Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Declaration on the Establishment of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Shanghai, China. 2001.

"Shanghai Cooperation Organization Official: Terrorism in Xinjiang Is a Close Variant of International Terrorism." Xinhua. June 09, 2014. Accessed March 2, 2016.

Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Shanghai Convention on Combatting Terrorism, Separatism, and Extremism. June 15, 2002.

Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Statement and Plan of Action by the Shanghai Cooperation Organization Member States and the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan on combating terrorism, illicit drug trafficking and organized crime. 2009.

Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Treaty on Long-Term Good Neighborliness, Friendship, and Cooperation Between the Member States of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan. 2007.

Shanghai Five. Treaty on Deepening Military Trust in Border Regions. Shanghai, China. 1996.

Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Declaration on the Establishment of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Shanghai, China. 2001.

The People's Republic of China's Ministry of Defense. China's National Defense in 2000, Beijing, China. 2000.

The People's Republic of China's Ministry of Defense. China's National Defense in 2002, Beijing, China. 2002.

The People's Republic of China's Ministry of Defense. China's National Defense in 2006, Beijing, China. 2006.

The People's Republic of China's Ministry of Defense. China's National Defense in 2008, Beijing, China. 2008.

The People's Republic of China's Ministry of Defense. China's National Defense in 2010, Beijing, China. 2010.

The People's Republic of China's Ministry of Defense. China's National Defense in 2015, Beijing, China. 2015.

The People's Republic of China's Ministry of Foreign Affairs. China's Position Paper on the New Security Concept, Beijing, China. 2002.

Wu, Guoguang, and Helen Lansdowne. "International Multilateralism with Chinese Characteristics: Attitude Changes, Policy Imperatives, and Regional Impacts." In China Turns to Multilateralism: Foreign Policy and Regional Security, 3-18. New York, NY: Routledge, 2008.

Wuthnow, Joel, Xin Li, and Lingling Qi. "Diverse Multilateralism: Four Strategies in China's Multilateral Diplomacy." Journal of Chinese Political Science 17, no. 3 (July 20, 2012): 269-90.

Zhao, Huasheng. "China's View of and Expectations from the Shanghai Cooperation Organization." Asian Survey 53, no. 3 (2013): 436-60.

Zhang, Yunling. "One Belt, One Road: A Chinese View." Global Asia 10, no. 3 (October/November 2015): 8-12.

Endnotes

- Abigail Grace wrote this paper as a Senior at Georgetown University's School of Foreign Service while majoring in International Politics: Security Studies. This piece was written to fulfill the Asian Studies Certificate's thesis requirement.

- Ann Kent, "China's International Socialization: The Role of International Organizations." Global Governance 8, no. 3 (2002): 343-64.

- Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Declaration on the Establishment of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Shanghai, China. 2001.

- At times, ASEAN+1 can refer to dialogue between ASEAN and either China, India, South Korea, or Japan. However, all references to ASEAN+1 in this piece solely refer to ASEAN/China dialogue.

- The People's Republic of China's Ministry of Defense. China's National Defense in 2000, Beijing, China. 2000.

- Gilbert Rozman, "Invocations of Chinese Traditions in International Relations." Journal of Chinese Political Science, 17, no. 1, (2012): 111-24.

- Caitlin Campbell, U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission. "Highlights from China's New Defense White Paper, ‘China's Military Strategy.'" Washington, DC. 2015.

- For information on US maritime dominance in the Pacific, see: George W. Baer, One Hundred Years of Sea Power: The U.S. Navy, 1890-1990. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1994. For information a general overview of ASEAN and the ARF, see: Alice D. Ba, "China and ASEAN: Renavigating Relations for a 21st-century Asia." Asian Survey 43, no. 4 (July/August 2003): 622-47.; also, Hiro Katsuma, ASEAN's Cooperative Security Enterprise: Norms and Interests in the ASEAN Regional Forum. (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009).

- Shanghai Five. Treaty on Deepening Military Trust in Border Regions. Shanghai, China, 1996. Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Declaration on the Establishment of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Shanghai, China. 2001.

- The People's Republic of China's Ministry of Foreign Affairs. China's Position Paper on the New Security Concept, Beijing, China. 2002.

- Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Declaration on the Establishment of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Shanghai, China. 2001.

- Alice D. Ba, "China and ASEAN: Renavigating Relations for a 21st-century Asia." Asian Survey 43, no. 4 (July/August 2003): 622-47.

- Ann Kent, "China's International Socialization: The Role of International Organizations." Global Governance 8, no. 3 (2002): 343-64.

- Association of Southeast Asian Nations. ASEAN Community 2016 Fact Sheet. Jakarta, Indonesia. 2016.

- See China's National Defense in 2000, 2002, 2004, 2006, 2008, 2010, 2015. cited throughout this work.

- The People's Republic of China's Ministry of Defense. China's National Defense in 2015, Beijing, China. 2015.

- The People's Republic of China's Ministry of Foreign Affairs. China's Position Paper on the New Security Concept, Beijing, China. 2002.

- The People's Republic of China's Ministry of Defense. China's National Defense in 2015, Beijing, China. 2015.

- The People's Republic of China's Ministry of Defense. China's National Defense in 2015, Beijing, China. 2015.

- The People's Republic of China's Ministry of Defense. China's National Defense in 2015, Beijing, China. 2015.

- Bates Gill, "China's New Security Multilateralism and Its Implications for the Asia– Pacific Region." In SIPRI Yearbook 2004, 210. Stockholm: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, 2004.

- Bates Gill, "China's New Security Multilateralism and Its Implications for the Asia– Pacific Region." In SIPRI Yearbook 2004, 208. Stockholm: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, 2004.

- Guogang Wu and Helen Lansdowne. "International Multilateralism with Chinese Characteristics: Attitude Changes, Policy Imperatives, and Regional Impacts." In China Turns to Multilateralism: Foreign Policy and Regional Security, 3-18. New York, NY: Routledge, 2008.

- Chien-Peng Chung, "The Shanghai Co-operation Organization: China's Changing Influence in Central Asia." The China Quarterly, 2004, 989-1009.

- Joel Wuthnow, Xin Li, and Lingling Qi. "Diverse Multilateralism: Four Strategies in China's Multilateral Diplomacy." Journal of Chinese Political Science 17, no. 3 (July 20, 2012): 269-90.

- Huasheng Zhao, "China's View of and Expectations from the Shanghai Cooperation Organization." Asian Survey 53, no. 3 (2013): 436-60.

- Yunling Zhang, "One Belt, One Road: A Chinese View." Global Asia 10, no. 3 (October/ November 2015): 8-12.

- All translations are the work of the author. Both the original Chinese documents and English translations provided by the PRC were utilized to determine phrases' connotations.

- "Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)." Nuclear Threat Initiative. October 21, 2015. Accessed March 13, 2016.

- To maintain consistency in translation, all documents below are the official English translation of the original Chinese documents. Translations were obtained from the PRC's State Information Council and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization's Secretariat.

- The People's Republic of China's Ministry of Defense. China's National Defense in 2000, Beijing, China. 2000.

- Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Declaration on the Establishment of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Shanghai, China. 2001.

- The People's Republic of China's Ministry of Defense. China's National Defense in 2006, Beijing, China. 2006.

- Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Treaty on Long-Term Good Neighborliness, Friendship, and Cooperation Between the Member States of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan. 2007.

- For examples of CCP-led connections between Uyghur separatism and Islamic extremism, see: "Beijing Inflicts a Defeat on Al-Qaeda." South China Morning Post, January 25, 2007. "Chinese FM Calls for United Front to Fight Terrorism." Xinhua. November 15, 2015. Accessed February 06, 2016. "Shanghai Cooperation Organization Official: Terrorism in Xinjiang Is a Close Variant of International Terrorism." Xinhua. June 09, 2014. Accessed March 2, 2016.

- For examples, see: Amnesty International. China: Gross Violations of Human Rights in the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region. Publication. 018th ed. Vol. 17. London: Amnesty International, 1999, 10. Amnesty International. People's Republic of China China's Anti-Terrorism Legislation and Repression in the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region. Publication. 010th ed. Vol. 17. London: Amnesty International, 2002. FIDH—International Federation for Human Rights, Antonie Bernand, Michelle Kissenkoetter, David Knaute, and Vanessa Rizk, The Shanghai Cooperation Organization: A Vehicle for Human Rights Violations. Paris, France, August 2012).

- Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Shanghai Convention on Combatting Terrorism, Separatism, and Extremism. June 15, 2002.

- The People's Republic of China's Ministry of Defense. China's National Defense in 2002, Beijing, China. 2002.

Appendix 1: Document Categorization

Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

John Howard, then-Prime Minister of Australia, claimed that, ‘I count it as one of the great successes of this country’s foreign relations that we have simultaneously been able to strengthen our long-standing... MORE»

The relationship between the People's Republic of China (PRC) and the Holy See appears to be an uneasy association between opposites. With over 1 billion people, the PRC is "the world's most populous state," while the Holy See is housed in tiny Vatican City.2 In addition to its status as a sovereign political entity,3 the Holy See... MORE»

Since the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, the Chinese Communist Party has used publicly displayed propaganda art as a means of maintaining power. During the early years of the PRC, propaganda posters played a large role in establishing a cult of personality around Mao Zedong. Today's propaganda art seeks primarily... MORE»

Regionalism, as Edward Mansfield describes, usually involves policy coordination through formal institutions within a region.1 Although there are conceptual debates surrounding what a region is and what regionalism is, empirically... MORE»

Latest in International Affairs

2022, Vol. 14 No. 04

With over 10 million stateless people globally, statelessness has increasingly become a pressing issue in international law. The production of statelessness occurs across multiple lines including technical loopholes, state succession, and discriminatory... Read Article »

2021, Vol. 13 No. 09

The COVID-19 crisis has exacerbated current global challenges. However, this article argues that this time of crisis can also be a unique opportunity for the existing global economic institutions - G20, WTO, IMF, and World Bank (WB) - to make the... Read Article »

2021, Vol. 13 No. 02

On January 1st, 1959, a small band of Cuban rebels shocked the world, overthrowing the American-backed dictator Fulgencio Batista. These rebels were especially known for their guerrilla tactics and their leaders, such as Fidel Castro and Ernesto... Read Article »

2021, Vol. 13 No. 01

Israel has increased the nation’s security presence around the Gaza Strip and in the West Bank. Here, the research project analyzes how transaction costs resulting from Israeli security policy impact the output of manufacturing activities... Read Article »

2020, Vol. 12 No. 09

The necessity of international relief is unending as new crises continue to emerge across the world. International aid plays a crucial role in shaping how affected communities rebuild after a crisis. However, humanitarian aid often results in a... Read Article »

2019, Vol. 11 No. 10

This article aims to present the biopiracy of traditional knowledge from India by the United States, which has occurred directly through the use of patent law and indirectly through economic power and cultural imperialism. Throughout this essay,... Read Article »

2018, Vol. 10 No. 10

After joining the European Union (EU) and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in 2004, Estonians felt secure and in charge of their future. However, following the 2007 Bronze Horseman incident in the Estonian capital of Tallinn which included... Read Article »

|