From Cornell International Affairs Review VOL. 10 NO. 1The Role of Female Quotas and Female Activism in Passing Gender Based Violence Legislation in Sub Saharan Africa: South Africa as a Case Study

By

Cornell International Affairs Review 2016, Vol. 10 No. 1 | pg. 1/1

IN THIS ARTICLE

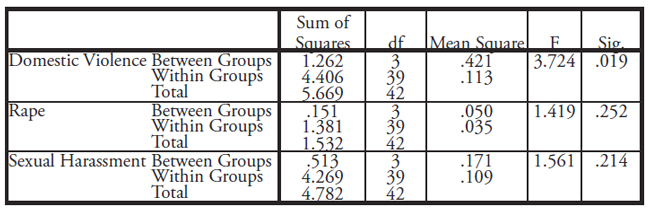

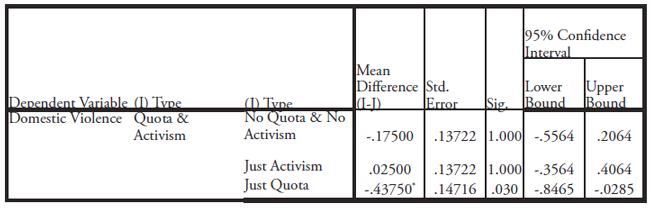

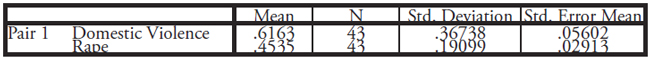

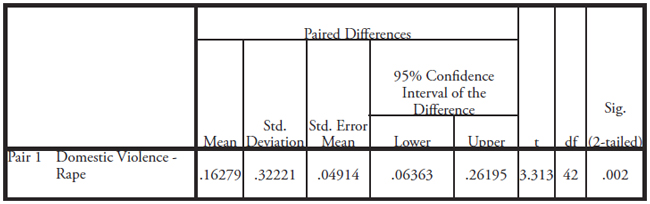

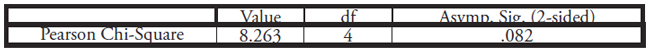

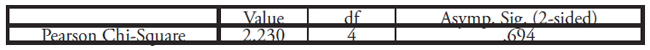

Introduction"One thing governments have got is legislation. Legislation has an impact. It affects millions of people in a country just by a stroke of a pen." – Executive Director of UN Women, Dr. Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, "Gender and Violence" Lecture, Yale University, November 6, 2015 In the 1900s, gender-based violence was commonplace throughout Sub-Saharan Africa. Surveys conducted in the region revealed that over 40% of Ugandan, Zambian, and Kenyan women, and 60% of Tanzanian women experienced regular physical abuse.2 Over 80% of married Nigerian women reported being verbally or physically abused by their husbands.3 In most countries, however, state assistance and legal protections were non-existent or nascent and very limited. In South Africa, for example, an abused woman could only seek state assistance through a "peace order." She could submit a complaint of abuse to a magistrate, who could order the abuser to act peacefully towards the female complainant for up to six months.4 The order was merely a warning, with no provision for arrest and prosecution if breached.5 At the turn of the century, the tide shifted alongside the emergence of global gender equality norms. Sexual violence legislation in many Sub-Saharan African countries became more robust. Today, many governments have committed to creating laws that effectively punish and eradicate gender-based violence. Each year, Sub Saharan Africans countries commemorate International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women and the 16 Days of Activism Against Gender-Based Violence Campaign that follow, which commenced in 1991 and coordinated by the Center for Women's Global Leadership.6 How did this drastic shift in the region take place? What specific factors, beyond global norms, led to several countries adopting significant gender-based violence legislation? This paper ascribes the change in large part to the involvement of female members of parliament (MPs) who had a history of activism in a strong feminist movement, and who subsequently entered the government through an electoral quota system. Drawing on data of gender-based violence legislation from 43 Sub-Saharan African countries and a case study of South Africa, this paper examines the effect of quota adoption and strong female activism in the passage of gender-based violence legislation. TheoryScholars have furthered several competing theories to explain how stronger genderbased violence preventive legislation emerged in many Sub-Saharan African countries in the late 20th and early 21st century. The most prominent theory attributes legislation to the increase in female political representation. Strategic Objective G of the 1995 Beijing Platform for Action, constructed at The Fourth World Conference on Women, advised both the government and political parties reform electoral law so that women could participate fully in policy-making structures.7 Before the Action Plan only four countries worldwide, Argentina, Belgium, Nepal, and Uganda, had a constitutional and/or election law gender quota for national parliament.8 By 2006, approximately 40 countries had introduced gender quotas in elections to national parliaments and more than 50 countries' major political parties had adopted party quotas.9 Scholars maintain that increasing the number of female elected officials advanced women's rights and policy concerns, such as gender-based violence issues, because women tended to promote women's issues once elected to political office.10 Cross-country quantitative analysis of 103 countries between 1970 and 2006 by political scientist Li-Ju Chen confirms that, globally, quotas are positively correlated with policy outcomes that concern women, such as health and education.11 Conversely, scholars S. Laurel Weldon and Mala Htun reason that feminist activism, rather than female quotas, lead to the adoption of stronger gender-based violence preventive legislation. Using an original dataset of social movements and violence against women policies in 70 countries over four decades, Weldon and Htun show that feminist mobilization in civil society by strong, local autonomous women's groups is the key to gender policy development.12 According to them, intralegislative political phenomena, such as leftist parties, economic factors like national wealth, and even women in government do not drive legislation.13 Women's movements and women's policy agencies are more effective venues for expression of women's viewpoint than the presence of certain women in legislatures because the former represent a multiplicity of female perspectives.14 Weldon finds that even where there are both female legislators and active women's movements, only autonomous movements engender gender-based violence initiatives, as the interactive effect between women's movements and the number of women in lower legislative houses in her 2002 study poorly predicts violence against female oriented policy outcomes.15 In analyzing gender outcomes in democratic transitions, political scientist Georgina Waylen argues that active, effective women's movements are a necessary, but insufficient condition for women's substantive representation. Examining the case of South Africa, Walyen ascribes successful legislative outcomes to a favorable political opportunity structure, namely the left leaning ideology of the ANC, and strategic organizing by key women actors, namely an effective alliance of feminists, activists, and academics with "sympathetic insiders" within government and parliament.16 Unlike Weldon, Waylen underscores the interactive effect between women's movements, academics, and legislators, highlighting the importance of communication and collaboration between the three groups. This paper challenges the conceptual validity of the conventional wisdom that quotas alone or activism alone lead to substantive representation. Acknowledging the importance of having both quotas and women's movements, this paper focuses on Waylen's "sympathetic insiders." Individual female legislators who have previously been on the outside and who have subsequently become "insiders" through quotas pass robust legislation and pave the way for future generations of parliamentarians to do so. To test the strength, scope, and generalizability of this theory, this paper quantitatively investigates the effect of quotas and female activism in feminist movements on the strength of gender-based violence legislation. The analysis confirms that activism is vital to achieving comprehensive legislation in Sub-Saharan African countries; quotas alone are not associated with strong gender-based violence legislation. Instead, as predicted by the interactive theory, it is countries that have both gender quotas and the feminist activism that are significantly more likely to adopt legislation against gender based violence. A case study on South Africa is developed to shed light on how exactly the combination of gender quotas and feminist activism come to result in stronger anti-gender based violence legislation. Quantitative Cross-Continent TestThis paper examines the strength of gender-based violence legislation in 43 Sub-Saharan African countries as reported in the 2014 Social Institutions and Gender Index. It tests the effect of having legislated and/or party quotas and female activism in these countries. This paper hypothesizes that countries in Sub-Saharan Africa with quotas and activism will have stronger gender-based violence legislation. Comparatively, countries with no quotas, just quotas, or just activism will have weaker legislation than countries with both. The first independent variable, quotas, are defined as legally binding commitments to place a certain number of women in governance structures, usually the national legislature. There are two prevailing types of quotas: legal quotas and voluntary party quotas. Legal quotas are mandated in a country's constitution or by law; they regulate the proceedings of all political parties and may prescribe sanctions for non-compliance.17 Legal quotas may consist of reserved seats to regulate the number of women elected or legal candidate quotas to set the proportion of women on candidate lists.18 Legal quotas may ensure representation at the subnational level and/or the national level in the lower house and/or the upper house. Voluntary party quotas are decided by one or more political parties in a country and are explicitly laid out in a political party's own internal regulations.19 After examining a country's quota system through the International IDEA/ Inter-parliamentary Union/Stockholm University Global Database of Quotas for Women and cross checking it with the Social Institutions and Gender Index database, this paper codes 1 for each country with voluntary party quotas or legislated quotas in the upper or lower house, and 0 for countries with no quotas or quotas only at the subnational level. As of 2014, there are 13 Sub-Saharan countries without party or legal quotas at the national level. Sub-Saharan countries, however, are constantly changing their governance and national representation structures. Yet, legislation takes time to be drafted, commented on, and passed, as exemplified in the passage of the Domestic Violence Act in South Africa. Thus this paper measures whether or not a country had a quota before 2012 to allow a two to three-year lag period in legislation following quota adoption. Countries that adopted quotas in the years 2012, 2013, and 2014 were coded with a 0—the number of countries without quotas, therefore, totals 20. This paper defines the independent variable of female activism as active participation in a feminist movement between 1990-2011. This paper follows Weldon and Htun's definition of a feminist movement as one coordinated to improve women's status and/or promote equality and/or end patriarchy. Although unlike Weldon and Htun, this paper recognizes women's organizations within political parties as feminist movements.20 Similar to the method adopted by Weldon and Htun to measure the existence of women's and feminist movements, this paper searches web-based material, academic research, human rights reports, and news media through the ProQuest search site GenderWatch and the Swarthmore University Global Nonviolent Action Database. Just as Weldon and Htun find, there tended to be few disputes among country experts about the existence and inception of a women's movement, making coding relatively easy. This same method is also used to measure women's movement strength. In general, web-based data, media outlets, and academic research already tend to disparately favor strong movements over weaker ones. This paper, following Weldon and Htun, officially recognizes movements as strong if they are described in narrative accounts as strong, influential, powerful, and mobilizing widespread public support. Countries where women have organized nonviolent protests or where women activists have organized around gender-related issues between 1990 and 2011 are coded as having female activism (denoted as 1). Countries that have not had strong female organized nonviolent protests or significant mobilization of women around gender-related issues in this period are coded as having no female activism (denoted as 0). As displayed in Table I, 25 countries in the dataset have strong female activism and 18 do not. In the dataset, strong female activism was most commonly in the form of female civil society groups and female wings of political parties fighting for social, economic, and political equality and the termination of harmful traditional practices, such as female genital mutilation (FGM). For example, in the GenderWatch search for Burundi (coded as having female activism), three articles immediately surfaced. They detailed women's organizations publicly advocating for political equality and female non-governmental organizations working with the government to promote women's human rights.21 In the GenderWatch search for Gambia (coded as having female activism), two articles immediately surfaced about females successfully organizing to end the practice of FGM.22 In the Global Nonviolent Action Database search for Kenya (coded as having female activism), two references emerged of female led nonviolent campaigns: one in which female organizations, primarily those explicitly for mothers, protested to release political prisoners and press for democratic reform during 1992-1993; and one in which several female coalitions and non-governmental organizations led a sex strike during 2009 to protest government inaction.23 Conversely, in the case of CongoBrazzaville (coded as not having activism), there were no female led nonviolent protests and only one GenderWatch article referencing a relatively unknown women's organization, the Congolese Association of Women Heads of Households'.24 As illustrated in Table I, Sub-Saharan African countries were placed in one of four categories: Quota Before 2012, Female Activism (Quota & Activism); Quota Before 2012, No Female Activism (Just Quota); No Quota Before 2012, Female Activism (Just Activism); and No Quota Before 2012, No Female Activism (No Quota & No Activism). 15 Sub-Saharan countries were found to have female activism and quotas (Quota & Activism); 10 to have activism without quotas (Just Activism); 8 to have quotas without activism (Just Quotas); and 10 to have neither quotas nor activism (No Quota & No Activism). While female activists can promulgate the adoption of quotas, this paper attempts to code quotas and female activism independently in the model. Quota adoption is not always endogenous to female activism. In her 2011 study of the international community's effect on quota adoption, Sarah Sunn Bush explains that quotas can often be externally imposed or encouraged, rather than locally derived. States dependent on foreign aid may be forced to adopt quotas or may adopt them independently for signaling purposes to garner domestic and/or international legitimacy.25 The somewhat balanced distribution between countries that have both quotas and activism and countries that have just quotas or have just activism may be reflective of Bush's finding. The coding of variables in the paper, however, makes it more likely for countries with both quotas and activism to have adopted quotas through activism. Measuring female organizing for political equality, among other female concerns, the female activism variable most often indicates a call for quota adoption on the ground. The impact of this difference between quotas adopted with internal support and quotas adopted primarily through influence of the international community will be revisited in the analysis of the results. For the dependent variable, each country was matched with its attending gender-based violence legislation score. For purposes of this paper, gender-based violence legislation is defined as legislation reflected in a country's criminal or civil code that addresses any form of violence against women. The data quantifying the comprehensiveness and relative strength of gender-based legislation was derived directly from the 2014 Social Institutions and Gender Index. The Index scored each of 108 countries on the comprehensiveness and strength of its domestic violence laws, rape laws, and sexual harassment laws respectively. While each issue area is distinctive, they all concern violence against women and could all vary on the basis of female activism and quota adoption. The 2014 Social Institutions and Gender Index scores 43 Sub-Saharan countries legislation on domestic violence, rape, and sexual harassment. The database gives each country a score of 0, .25, .5 .75, 1 for its laws relating to each issue area. A country earns a 0 when there is specific legislation in place to address the issue in question, the law is adequate overall, and there are no reported problems of implementation; a country earns a 0.25 when there is specific legislation in place to address the issue, the law is adequate overall, but there are reported problems of implementation; a country earns a 0.5 when there is specific legislation in place to address the issue, but the law is inadequate; a country earns a 0.75 when there is no specific legislation in place to address the issue, but there is evidence of legislation being planned or drafted; and a country earns a 1 when there is no legislation in place to address the issue in question (all scores are displayed in Table II).26 To measure the effect of quotas and female activism on a country's genderbased violence legislation, a One-Way Anova test was conducted. The OneWay Anova test measures the difference in mean legislation scores between and within each of the four groups (No Quota & No Activism, Just Quota, Just Activism, Quota & Activism). The results of the One-Way Anova test are displayed in Tables III and IV. The difference in rape legislation scores and sexual harassment scores for the four groups is not statistically significant. The difference between the four groups in terms of domestic violence legislation scores, however, is statistically significant (Table IV, p-value=.019). The Bonferonni comparison (Table V) breaks down the One-Way Anova test. It determines whether the mean domestic violence legislation score for countries in the Quota & Activism group differs significantly from that of each of the other groups. The Quota & Activism group's mean legislation score is significantly different from the mean score of the Just Quota group (Table V, p-value=.030). To further test whether quotas, female activism, and their interaction (Quota & Activism) are significant predictors of domestic violence legislation generally, this paper uses a crosstab chi-squared test. The chi-squared test determines whether or not one can reject the null hypothesis that quotas, activism, or their combination individually do not have any effect on domestic violence legislation scores. As illustrated in Tables X and XI, having quotas is not a significant predictor of domestic violence legislation (Table XI, p-value = .694). Surprisingly, having both quotas and activism does not appear to be a significant predictor of legislation, either (Table XIII, p-value = .383). Activism alone, however, is a significant predictor of at the .1 level (Table IX, p-value = .082). Cross-Continent Analysis: Rape, Sexual Harassment, and Domestic ViolenceBased on the statistical tests, domestic violence legislation is the only type of legislation that differs significantly across countries in each of the four groups. Rape and sexual harassment legislation do not appear to differ across countries on the basis of quota implementation and female activism. With respect to rape, this finding is not altogether surprising. Relative to rape, domestic violence legislation likely has a significant trend because it is a more controversial, progressive issue area. Several Sub-Saharan African countries have had legislation outlawing rape in their penal and criminal codes for centuries. While certain rape legislation may be more progressive, including punishments specifically for intimate partner rape or gang rape, stranger rape is largely uncontroversial. The 2014 Social Institutions and Gender Index merely measured if rape was illegal in any form. Thus, in the coding process, not a single Sub-Saharan African country earned a score of 1 for rape legislation (Table II). Moreover, countries like South Africa, which adopted new, progressive and comprehensive rape laws in 2007 that recognize multiple forms of rape, and countries such as Guinea-Bissau, where rape, albeit spousal rape included, is merely criminalized in criminal codes, earned identical scores of .25.27 It is possible that, if rape legislation were measured in terms of progressiveness, punishment, or specificity, significant differences would have emerged. Conversely, significant differences between rape and domestic violence in Sub-Saharan Africa may be accounting for the results as they are presently calculated. Conducting a paired t-test between the domestic violence legislation scores and the rape legislation scores in the database, the mean domestic legislation score is significantly larger than the mean rape legislation score (Table VII, p-value=. 002). Unlike rape, domestic violence is more likely to directly conflict with many African non-doctrinal policies (customary law, religious law, custom, and tribal authority). Customary law is essential to many Sub-Saharan African countries and has been imbued with authority in many African constitutions. In matters such as marriage, inheritance, and traditional authority, however, customary law often discriminates against women. Practices such as bride price, guardianship, and inheritance place women under the rule of their husbands, brothers, and fathers.28 Passing legislation that protects women from the men of their households and provides women with legal leverage directly contradicts the underlying principle of these customs. It is not surprising that their passage would require extra strength and mobilization on the part of women in government who have engaged in female activism. With respect to sexual harassment, the finding is no less surprising. There were distinct measurement issues in the sexual harassment legislation similar to those in the rape measurements. While most countries in the database had specific legislation that addressed domestic violence alone, the legislation that addressed sexual harassment was part and parcel of larger reforms making sexual harassment illegal in certain settings. For example, in the case of Botswana, the Public Services Act (1999) makes sexual harassment specifically in public services a criminal offense.29 The coding system did not take into account the varied contexts of sexual harassment legislation and merely coded a country as having legislation if sexual harassment was outlawed in at least one context. The measurement of sexual harassment legislation, therefore, may not be adequate. It is possible that, if the sexual legislation were measured in terms of the singularity of the law, the comprehensiveness of contexts, progressiveness, punishment, or specificity, differences would have emerged. However, it is also possible that female legislators and female activism have no significant effect on sexual harassment because it is not a first order issue. Sexual harassment often does not escalate to the level of violence associated with rape and domestic violence. The violence component of sexual harassment legislation most often deals with harassment in the workplace. It is not as painful, inescapable, or all encompassing as the physical and psychological brutality of domestic violence. As such, ending sexual harassment is frequently not a priority for female activists. In the countries coded as having female activism on the basis of the material contained in the GenderWatch search and the Swarthmore University Global Nonviolent Action Database, sexual harassment was never a focal point of activism and did not surface as a primary concern of the female activists. Marriage laws, land and property rights, education, FGM, and domestic violence were the most common concerns amongst female activists. Cross-Continent Analysis: Domestic ViolenceIf we limit the analysis to domestic violence legislation, having both activism and quotas is significantly better than having just quotas. According to the Bonferroni comparisons test (Table V), the mean domestic violence legislation score for countries in the Just Quota group (N=8, Mean=.9375) is significantly higher than the mean domestic violence legislation score for countries in the Quota & Activism group (N=15, Mean=.5000). As a score of 0 signaled specific, adequate legislation with no reported problems of implementation, lower means signify more comprehensive legislation. This result strongly indicates that, Sub-Saharan African countries with activism and quotas have significantly more comprehensive legislation than those with just quotas. In the chi-squared test, quotas irrespective of activism (N=20) are not a significant predictor of legislation (Table XI). While the combination of quotas and activism (N=15) is also insignificant (Table XIII), results do improve when activism is added to the model. The p-value gets smaller, more closely approaching significance at the .1 level, and the chi-squared variable increases (Table XIII). This result in conjunction with the Bonferonni comparison suggests that, in order for electoral quotas to engender successful legislation, it is beneficial for countries to have female activism. Investigating why quotas themselves are insignificant, this paper first considers potential measurement issues in the quotas variable that may have caused any one country to skew results. In countries like Sudan and Somalia where there is current conflict, weak state capacity, and high unrest, it is not only difficult to obtain sound data on legislation and its implementation, but it is also highly unlikely that quotas are in effect. In Botswana, Cote d'Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), and Eritrea, voluntary party quotas and even legal quotas have not been enforced. In Botswana, while the Botswana Congress Party and the Botswana National Front introduced 30% voluntary party quotas for women on electoral lists, both parties have not always met this target.30 Similarly, while the Ivorian Public Front has had a 30% quota for women since 2001, the quota has not always been achieved in practice. In fact, the total percentage of women representatives fell from 21% in 2010 to 14% in 2011.31 In the DRC, there are no enforcement or monitoring mechanisms to ensure legal quotas are met. The electoral law does not provide any sanction for non-compliance with the parity principle and non-compliance does not necessitate the rejection of a candidate list.32 The DRC has, thus, consistently fallen short of equal representation. In the 2011 legislative elections, for example, women constituted roughly 12% of the total number of candidates and subsequently won only 9% of the seats in the National Assembly.33 In Eritrea, despite the adoption of a legal quota for women in the lower house in 2001, no democratic elections have been held. The parliamentary elections scheduled for December 2001 were postponed indefinitely. As such, the quota provisions have not yet been implemented.34 Measuring quota adoption, this paper codes Cote d'Ivoire, the DRC, Eritrea, and Somalia and Sudan, as having adopted quotas before 2012. Yet, as quotas have only been promised and not put into practice, gender-based violence legislation in these countries cannot be attributed to quota adoption. After dropping Sudan, Somalia, Botswana, Eritrea, DRC, and Cote d'Ivoire from the model and running the crosstab of the effect of quotas again, however, results remain insignificant (Table XV, p-value= .960). To examine whether or not the type of quota adopted affects legislation, this paper tests the effect of four possible kinds of quotas adopted in Sub-Saharan African countries on domestic violence legislation. Running crosstab chi-squared tests of party quotas and legal quotas (dropping Sudan, Somalia, and Eritrea where quotas definitively are not implemented), this paper finds neither party quotas (Table XVII, p-value= .602) nor legal quotas (Table XIX, p-value= .776) to be significant predictors of domestic violence legislation. Moreover, neither legal quotas for the lower house (Table XXI, p-value= .776) nor legal quotas for the upper house (Table XXIII, p-value= .233) are significant predictors. These findings suggest quota adoption, irrespective of the type, does not significantly affect domestic violence legislation in Sub-Saharan countries. This paper postulates that quotas generally, regardless of type, are insignificant because they do not ensure that women's voices are heard and women's concerns are championed. When a society adopts quotas as a means of signaling international and/or domestic legitimacy as Bush (2011) suggests, quotas may be mere tokens of equality. In those countries, the socio-political environment and societal values may be extremely patriarchal, adverse to female engagement in politics. Moreover, women in office may not necessarily favor strong genderbased violence preventive legislation, especially if they have not been exposed to activists' framing of the issue. As the Bonferonni comparison (Tables V) indicates, countries having both quotas and activism have significantly more comprehensive legislation than those with just quotas. This paper poses three potential explanations for this finding. First, countries that have both activism and quotas are likely to abide by quota requirements because they are internally adopted. Because the female activism variable captured women's organizing for political representation, countries with both were more likely to have internally adopted quotas with the aid of feminist activism. Second, countries that have both activism and quotas may generally have environments more conducive to female political participation and female-friendly legislation. Activism may widen the political space, pave the way for women's voices to be heard, and frame gender-based violence as focus area for female MPs. This reflects what Waylen calls an effective alliance of feminists, activists, and academics with "sympathetic insiders" within parliament and government. Third, countries that have both activism and quotas could have female MPs with strong backgrounds in female activism. The female MPs may be precisely those feminist activists that pressed for quotas. It is possible, however, that quotas and activism may improve legislation because of the explanatory power of activism. In the chi-squared tests, activism is the only variable that significantly predicts domestic violence legislation (Table IX, p-value = .082). This result supports Weldon and Htun's finding that strong female movements in civil society affect policy and legislative outcomes. Coalitions of female activists with strong community ties may be better positioned than female MPs to understand and lobby for female concerns. Activism over a long period of time may also engender legislation without quotas. Additionally, it is important to note that the quantitative tests do not fully account for timing and sequencing. Countries with better legislation regarding women's rights may encourage activism and quota adoption. The case study of South Africa addressed next accounts for this concern, confirming that most often both activism and quotas lead to more comprehensive female-centric legislation. Overall, with 43 observations broken down further into groups of 15, 10, and 8 observations in the quantitative tests, it is difficult to be fully confident in the data. Each country carries a significant weight in the model. Any single country could be the driving force behind the trend or could be skewing the results. It is also possible that several country-specific variables not measured in the model have caused present trends in the data. For instance, the level of democratization and development could affect quota implementation, female activism, and domestic legislation. Undemocratic countries, with no civil and political liberties, may prohibit activism and will likely have legislation that is weak and/or does not represent popular opinion. Conversely, countries with more entrenched democratic principles, may have a more vibrant civil society and stronger legislation. Likewise, developed countries may be more likely to have female quotas, a more established civil society, and a more advanced legislative process conducive to femalefriendly legislation. Conflict specific variables may affect results as well. In her newly published book, Women and Power in Postconflict Africa, scholar Aili Mari Tripp finds that post-conflict countries in Africa have twice as many women in legislatures and have passed twice the amount of female-friendly legislation as non-post conflict countries in the continent.35 She explains that the post-conflict environment can disrupt gender roles and create opportunity structures for women to engage in politics.36 This would open the space for increased female activism, female political representation and, ultimately, female-friendly legislation. She also informs that post-conflict countries in Africa have high levels of international involvement.37 International actors often press for international norms and could coerce or induce quota adoption, civil society development, and comprehensive legislation. Additionally, the level or intensity of gender-based violence in each country, largely affected by conflict, may also give rise to countries differing in the priority placed on gender-based violence in their legislative agendas. The likely influence of development, democracy, and post-conflict effects is a limitation of the current quantitative model. While the case study below allows for more confidence in the proposed theory, controlling for and testing the effects of development and democracy levels and post-conflict variables in future models will lead to further certainty. Case Study: South AfricaThis paper uses in-depth study of South Africa to more closely examine the theory that both female activism and quotas promote the adoption of gender-based violence preventive legislation, specifically legislation that addresses domestic violence. This paper chose the case of South Africa because it is widely cited as a success story and extensively studied in scholarly accounts. Many consider South Africa to be the best-case scenario where quotas led to adoption of comprehensive domestic violence policy and legislation. Prior to quota adoption, legislation was negligible and, despite a high prevalence of gender inequality and violence against women, women's concerns were largely absent from law and policymaking. With quota adoption, however, female MPs entered the government after the process of democratization, promoted national gender machinery, and championed feminist concerns. Investigating South Africa through historical accounts, in-person interviews, and analyses of National Assembly debates, to determine which variables are most informative provides a nuanced picture through which to expand the theory. From the detailed case study, activism emerges as essential to each stage of the process. Female activist framing of gender as a central tenet of the larger liberation struggle heavily informed quota adoption, national gender machinery, and, ultimately, legislation. Having active female activists makes substantive representation of women's concerns through quotas more likely. South Africa has a long history of oppression, violence, and political and social marginalization. From colonial times until the first free and fair elections of 1994, a system of apartheid segregated the country and reserved social, political, and economic rights in South Africa for white citizens.38 While male anti-apartheid activists dominated the international spotlight, women mounted strong resistance to the apartheid regime. Female activists were crucial to the successful toppling of the apartheid government, engaging in mass action, female coalition building, and national mobilization long before their male counterparts, serving as the "backbone" of the movement.39 In 1918, women within the main resistance party, the African National Congress (ANC), formed their own league, initially named the Bantu Women's League and later called the ANC Women's League (ANCWL).40 When ANC activism accelerated in the 1950s with the Defiance Campaign to protest apartheid laws, women of the ANCWL participated in and led several protests across the country.41 Prominent female activists formed the Federation of South African Women (FSAW) in April 1954, a national women's organization across party, color, and socio-economic lines.42 In its first meeting, FSAW adopted a Women's Charter, expressly committing to the advancement of all women.43 FSAW vowed to "teach men they cannot hope to liberate themselves from the evils of discrimination and prejudice as long as they fail to extend to women complete and unqualified equality in law and practice,"44 framing gender as a central component of the larger effort to transcend social inequities instituted by the apartheid regime. FSAW led many anti-pass campaigns45 across the country, its greatest accomplishment being the 1956 Women's March. On August 9, 1956, commemorated today as Women's Day in South Africa, thousands of women from across the country flocked to the Union Buildings in Pretoria and presented a petition against pass laws to the head of the ruling party, The National Party (NP).46 When the system of apartheid finally began to fissure, formal negotiations for transition began. As predicted by scholar Lisa Baldez' theory of female mobilization in democratic transition, women in South Africa mobilized on the basis of their gender identity in the transition to democracy because they had sufficient resources, experience framing issues, and were originally excluded from the agenda setting process.47 In 1992, experienced women leaders from across South Africa, in over ninety organizations, united to ensure a place for women in the new democracy, forming the Women's National Coalition (WNC).48 Led by ANCWL members, the WNC broadened the political arena to ensure female participation in negotiations and to caucus around gender issues crucial to the transition.49 When negotiations for the interim constitution and bill of rights began, the multiparty body formed to negotiate the transition was male dominated. Through their collective action, however, women from the WNC convinced the formal body to allow each party's negotiating team one additional female. Women from across party lines worked with ANC women to incorporate gender equity and anti-discrimination practices into the new governance structure.50 As a result, the 1993 interim Constitution eradicated all forms of social inequality, including gender.51 ANC women also pushed to alter the formal party rules and practices to increase their participation, representation, and influence, securing the 30% quota for women on the party's national election list beginning in the first free and fair election in 1994.52 As South Africa adopted a proportional representation system with closed party lists, this was a significant step.53 Today, the Bill of Rights and the 1996 Constitution ensure women's rights, prohibit sex discrimination, and promote women's equality. National gender machinery, specific government structures and processes in the executive and legislative branches, promote and monitor progress toward gender equity. As illustrated in Figure I, both the executive and parliamentary bodies have defined channels of communication with female civil society organizations, ensuring continued representation of the female voice.54 Female activists have taken advantage of this machinery and female quotas, entering parliament in droves. Following the 1994 election, women were significantly represented in all government structures, accounting for 15% of ministers and 56% of deputy ministers in the cabinet and 27.7% of parliamentary seats.55 Although the "social" portfolios (health, welfare, housing) were assigned to women, women were also deputy ministers of "hard" portfolios (finance, and trade and industry).56 With a strong female presence post-quota implementation, parliament passed the Domestic Violence Act (no. 118 of 1998). Gender-based violence plagued South Africa and domestic violence was rampant. The year the Act was debated in parliament, one in four South African women reported being assaulted by her boyfriend or husband every week; 80% of the violence women suffered was in their homes at the hands of the men who supposedly supported and loved them.57 The Act significantly altered the legal protective framework available to these women. It broadened the international definition of "domestic-relationship" to include any relationship where persons of the same or opposite sex live or lived together.58 When violent acts transpired, the Act implemented a system of "speedy redress." It instructed South African Police to render service as soon as possible, allowed peace officers to arrest a respondent at the scene without a warrant, called on courts to accept ex parte applications on behalf of a complainant for a protection order, and permitted courts to grant an interim order if they were satisfied with prima facie evidence.59 South African Police were required to inform complainants of their rights, formally defining their failure to do so as misconduct in terms of the South African Police Services Act.60 Markedly, the Act also mandated that the state undertake financial assistance, when the complainant did not have the means to pay for the serving of documents, although no direct budget was set to implement this measure.61 While the Act passed with strong support from across party and gender lines, female MPs were the driving force behind the legislation. They engaged in agenda setting and brought national attention to the issue. In the first years of the new Parliament, gender equality was not a priority and gender equality bills languished in the South African Law Commission (SALC, the legislative drafting agency).62 The Minister of Welfare and Population Development Geraldine Fraser-Moleketi and the Deputy Minister of Justice Dr. Manto Tshabalala-Msiman took matters in their own hands. They spearheaded public education campaigns, organized workshops within the Department of Justice on dealing with cases involving violence against women, and collaborated heavily with civil society.63 They helped form an ANC Women's Caucus to garner public support for gender-based issues in the legislature. The Caucus worked at the grassroots level, creating the Joint Civil Society-ANC Parliamentary Women's Caucus Campaign to End Violence Against Women and Children.64 Because ANC women had previously worked alongside civil society members as activists in the liberation movement, they recognized the importance of continuing the partnership with those aligned with the cause. As Fraser-Moleketi explains, ANC female MPs and female ministers knew gender-based violence was an issue common to all women, regardless of race and class; they were prepared to fight for legislation and engage with civil society because they were informed by their past active involvement.65 With respect to the legislation, female MPs ensured the Act met international standards and worked to draft and process the legislation in time for formal negotiations. The Joint Monitoring Committee on the Improvement of the Quality of Life and Status of Women (JMC), created in 1966 by then Speaker of the National Assembly, an ANCWL member and former WNC founder, monitored all legislation for gender sensitivity to ensure the government fully implemented responsibilities set forth in the CEDAW.66 Under the leadership of former activist and female MP Pregs Govender, the JMC became a highly visible, consistent, and effective voice for women. It and promulgated domestic violence issue.67 When it was clear the SALC would not have a draft bill proposed before the 1999 elections, Govender devised a strategy to ensure a gender-based violence bill entered the 1998 Parliamentary discussions.68 With support from the ANC Women's Caucus, she bypassed the public hearing SALC process and, instead, allowed the public to comment on the draft bill at the parliamentary public hearings.69 When the SALC rejected the bill because of its gender-specific legislation, Govender convinced others in parliament to edit and process the Bill for debate just before end of the first term of Parliament.70 While scholar Shareen Hassim argues that the legislative gains made in the first five years of the democratically elected government can be attributed to notable women, "such as Pregs Govender, who would probably have been on the ANC list without a quota," voluntary party quotas were essential to getting these women in office.71 When interviewing Fraser-Moleketi, she divulged that after her involvement in the liberation movement, she and her husband agreed he would be in the provincial executive and legislature and she would spend more time with their children.72 Yet, when the ANC drafted its list, very clearly wanting a minimum of 30% women, party members approached Fraser-Moleketi. They wanted capable women like her, who had been part of the movement in exile and who had worked internally with party structures, to sit in the National Assembly.73 As Fraser-Moleketi explains, "Parliament was very receptive" because the Bill had the support of sympathetic, progressive men and, more importantly, a larger number of ANC women in the executive and the legislature.74 Analyzing the November 2nd debate of the draft Bill, the importance of former female activists in the government is clear. Of the 490 members of the National Assembly and the National Council of Provinces at that time, 117 were women. All 117 had been involved in activism and had been members of one of the broad-based women's coalitions, and 96 of the 117 were ANC members who had been elected through party quota.75 ConclusionAnalyzing the long history of female activism, the adoption of party quotas by the ANC, and the passage of the 1998 Domestic Violence Act in South Africa, women in government who were anti-apartheid activists stand as beacons of change. During apartheid, women in South Africa formed interracial and interparty coalitions to further gender equality. They framed female liberation as essential to the broader anti-apartheid struggle and solidified female representation in the agenda setting processes and in the formal government. When women entered the government in 1994, after theANC party quota, they provided a strong support base through which to pass progressive, gender legislation. The Domestic Violence Act, in particular, can be exclusively accredited to the labor of Pregs Govender, Geraldine Fraser-Moleketi, and Dr. Manto Tshabalala-Msimang. While conventional wisdom asserts that substantive legislation follows quota adoption, quotas alone were insufficient in the case South Africa and in other countries on the Continent. The results from the One-Way Anova test, the Bonferonni comparison, and the chi-squared tests of the quantitative model in this paper indicate that successful domestic violence legislation depends on more than just quotas. Because domestic violence is most often a first order issue in conflict with customary African laws, passing it likely requires the specific skills of former activist female MPs in comparison with rape and sexual harassment legislation. Quotas themselves are insufficient. Having activism present too appears to makes quotas more successful in achieving substantive legislation. While this paper offers several potential explanations for this finding, analyzing the finding in light of South Africa informs that female activism is likely important because of the expertise women acquire as activists. Women who have had first-hand experience coalition-building, framing gender issues, and fighting for their voices to be heard have the necessary wherewithal to pass domestic violence legislation. To more conclusively determine that women's activism experience is the driver of changes in legislation, one should control for development and democracy levels and post-conflict variables in future models. Ultimately, though we can reasonably conclude that, with respect to domestic violence legislation, adopting quotas to ensure female representation in government will not guarantee legislation. The environment within which quotas are adopted matters. Having individual female legislators with experience organizing and framing gender issues will make for far more successful legislative initiatives. If these women are active, they can enter government through quotas, or even work alongside MPs from a civil society vantage point, to aid the passage of domestic violence legislation. Women who enter government, however, without this experience, merely because of a top-down adoption of an electoral quota, will not have the framing, mobilizing, and legislative tools to make significant change. Successful legislation cannot emanate from quotas alone. Of course, legislation is merely a first step. In their interviews, Geraldine Fraser-Moleketi and Charlene Smith both emphasized the importance of comprehensive policies, aggressive implementation, and attitude and mindset shifts. In her talk at Yale, Dr. Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka advocated for a comprehensive approach on the part of the global community, local government and civil society members, and the individual, to end gender-based violence—"because causes are complex, the approach needs to be comprehensive."76 In her Parliamentary address on the day that the Domestic Violence Bill was being negotiated, Dr. Manto Tshabalala-Msimang recognized, "we cannot change the mindsets and attitudes of the people through legislation alone."77 For real change in behavior to occur, shifts in individual consciousness are vital. As Smith commented, "you can't legislate away gender-based violence."78 Despite significant strides, gender-based violence rates remain high in most Sub-Saharan African countries. In fact, since 2004, South Africa has had the highest incidence of recorded rape in the world.79 This paper recommends further research of the components necessary for successful implementation of legislation, apart from passage of legislation. Legislation, however, should not be discounted. Legislation can entrench principles of equality and can set the framework for further interventions that work to eradicate violence. As Dr. Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka articulated, legislation can affect "millions of people in a country just by a stroke of a pen." ReferencesBaldez, Lisa. "Women's Movements and Democratic Transition in Chile, Brazil, East Germany, and Poland." Comparative Politics Vol. 35 No. 3. 2003. Britton, Hannah Evelyn. Women in the South African Parliament: From Resistance to Governance. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. 2005. ——————."Organising against Gender Violence in South Africa." Journal of Southern African Studies Vol. 32 No. 1. 2006. Bush, Sarah Sunn. "International Politics and the Spread of Quotas for Women in Legislatures." International Organization 65. 2011. Chen, Li-Ju. "Do Gender Quotas Influence Women's Representation and Policies?" The European Journal of Comparative Economics Vol. 7 No. 1. 2010. Dahlerup, Drude and Lenita Freidenvall. "Quotas as a ‘Fast Track' to Equal Representation for Women: Why Scandinavia is No Longer the Model." International Feminist Journal of Politics Vol. 7 No. 1. 2006. Department of Women. "Joint Parliamentary Debate on 16 Days of Activism." Polity.org. Accessed 11/29/15. http://www.polity.org.za/article/joint-parliamentdebateon-16-days-of-activism-2015-11-10 Federation of South African Women. Women's Charter. Johannesburg. 17 April 1954. Franceschet, Susan, Mona Lena Krook, and Jennifer M. Piscopo. "Conceptualizing the Impact of Gender Quotas." In Impact of Gender Quotas. Edited by Susan Franceschet, Mona Lena Krook, and Jennifer M. Piscopo. New York: Oxford University Press. 2012. Fraser-Moleketi, Geraldine. Interview with the author. November 15, 2015. Hansson, Desirée and Beatie Hofmeyr. "Women's Rights: Towards a NonSexist South Africa." Johannesburg: Centre for Applied Legal Studies, Developing Justice Series No. 7. Undated. Hassim, Shireen. The ANC Women's League: Sex, gender and politics. A Jacana Pocket History. Jacana Media (Pty) Ltd: South Africa. 2014. ——————. Women's Organizations and Democracy in South Africa Contesting Authority. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. 2006. Hill, Leslie. "Redefining the Terms: Putting South African Women on Democracy's Agenda." Meridians Vol. 4 No.2. 2004. Htun, Mala and S. Laurel Weldon. "The Civic Origins of Progressive Policy Change: Combating Violence against Women in Global Perspective, 1975-2005." American Political Science Review Vol. 106 No. 3. 2012. Human Rights Watch. "SOUTH AFRICA: The State Response to Domestic Violence and Rape." 1995. International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance. Stockholm University and Inter-Parliamentary Union. Quota Project: Global Database of Quotas for Women. 2015. Inter-Parliamentary Union. "Women in National Parliaments: Situation as of 25 December 1997." Accessed 11/29/15. http://www.ipu.org/wmn-e/arc/classif251297.htm ——————. "Women in National Parliaments: Situation as of 1 November 2015." Accessed 11/29/15. http://www.ipu.org/wmn-e/world.htm Lodge, Tom. "South Africa." In Compendium of Elections. Edited by Tom Lodge, Denis Kadima and David Pottie. EISA. 2002. Meintjes, Sheila. "The Politics of Engagement: Women Transforming the Policy Process—Domestic Violence Legislation in South Africa." In No Shortcuts to Power: African Women in Politics and Policy Making. Edited by Anne Marie Goetz and Shireen Hassim, Zed Books, 2003. Mlambo-Ngcuka, Dr. Phumzile."Gender and Violence." Lecture. Yale University. November 6, 2015. Myakayaka-Manzini, Mavivi. "Women Empowered – Women in Parliament in South Africa." In Women in Parliament: Beyond Numbers. International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, Handbook. Stockholm, International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance. 2002. NationMaster. "Crime: Rape Rate: Countries Compared." Accessed 11/29/15. http://www.nationmaster.com/country-info/stats/Crime/Rape-rate Ndulo, Muna. "African Customary Law, Customs, and Women's Rights." Cornell University Law Faculty Publications. 2011. Odunjinrin O. Wife battering in Nigeria. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1993. Parliament of South Africa. "16 Days of No Violence Against Women Campaign." Accessed 11/29/15. http://www.parliament.gov.za/live/content.php?Item_ID=667&Revision=en/4&SearchStart=0 PR Library. "Proportional Representation Voting Systems." Accessed 11/29/15. https://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/polit/damy/BeginnningReading/PRsystems.htm ProQuest. Gender Watch Database. Accessed 12/8/15. http://www.proquest.com/products-services/genderwatch.html Rape Crisis Cape Town Trust. "Political Transition and Sexual Violence." Accessed 12/3/15. http://rapecrisis.org.za/rape-in-south-africa/ Republic of South Africa. 1998 Hansard Debates of the National Assembly. 2nd Parliament: 2nd session: no.1. November 2, 1998. ——————. The Interim South African Constitution. 1993. Shifman, Pamela, Nozizwe Madlala-Routledge, and Viv. "Women in Parliament Caucus for Action to End Violence." Agenda: Empowering Women for Gender Equity No. 36, No to Violence. 1997. Smith, Charlene. Interview with the author. November 5, 2015. Social Institutions & Gender Index. "Information about variables and data sources for the 2014 SIGI." OECD Development. 2015. Accessed 11/29/15. http://www.genderindex.org/data/ South African History Online. "The turbulent 1950s-Women as defiant activists." Accessed 11/29/15. http://www.sahistory.org.za/topic/turbulent1950s-women-defiant-activists Swarthmore University. Global Nonviolent Action Database. Accessed 12/8/15. http://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/ Tripp, Aili Mari. Women and Power in Postconflict Africa. New York: Cambridge University Press. 2015. United Nations Division for the Advancement of Women and UN Office on Drugs and Crime. "Violence against women: Good practices in combating and eliminating violence against women." Expert Group Meeting. 17 to 20 May 2005. Vienna, Austria. United Nations General Assembly. The Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women. A/RES/48/104. 20 December 1993. United Nations Women. "16 days of activism: 2015." UN WOMEN. Accessed 11/29/15. http://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/ending-violence-against-women/take-action/16-days-of-activism ——————. Beijing Platform for Action. United Nations Fourth World Conference on Women. Beijing, China. September 1995. UNICEF. "South Africa: Thuthuzela Care Centres." UNICEF. 2008. Accessed 11/29/15. http://www.unicef.org/southafrica/hiv_aids_998.html U.S. Department of State. "The End of Apartheid." Accessed 11/29/15. http://2001-2009.state.gov/r/pa/ho/time/pcw/98678.htm Waylen, Georgina. "Women's Mobilization and Gender Outcomes in Transitions to Democracy The Case of South Africa." Comparative Political Studies Vol. 40 No. 5. 2007. Weldon, S. Laurel. "Beyond Bodies: Institutional Sources of Representation for Women in Democratic Policymaking." The Journal of Politics Vol. 64 No. 4. 2004. ——————. "Inclusion, Solidarity, and Social Movements: The Global Movement against Gender Violence." Perspective on Politics Vol. 4 No. 1. 2006. ——————. Protest, Policy, and the Problem of Violence Against Women: A Cross-National Comparison. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press. 2002. Women's Section, The. Malibongwe Papers. January 1990. Wood K, Jewkes R. "Violence, Rape, and Sexual Coercion: everyday love in a South African township." Gender & Development. 1997. Endnotes

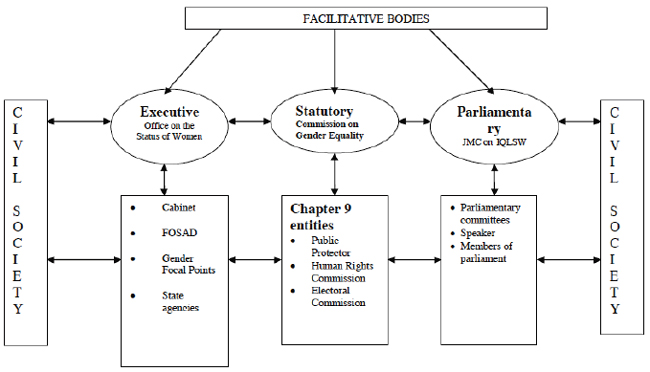

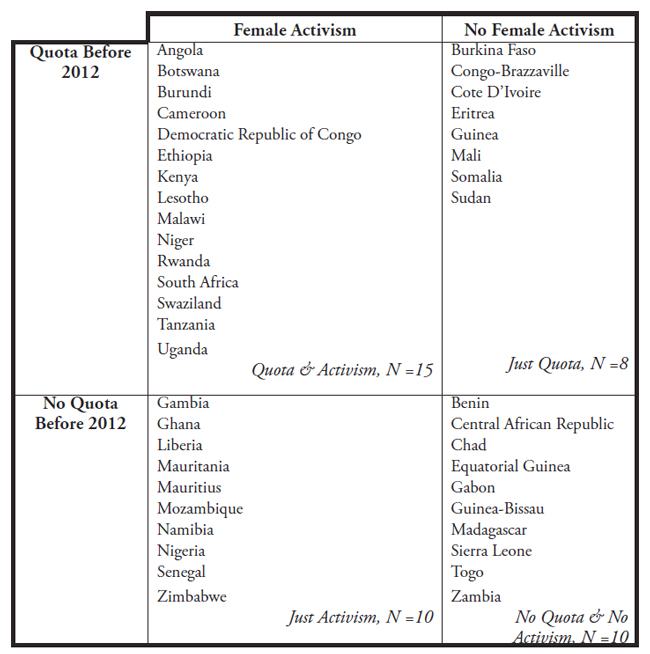

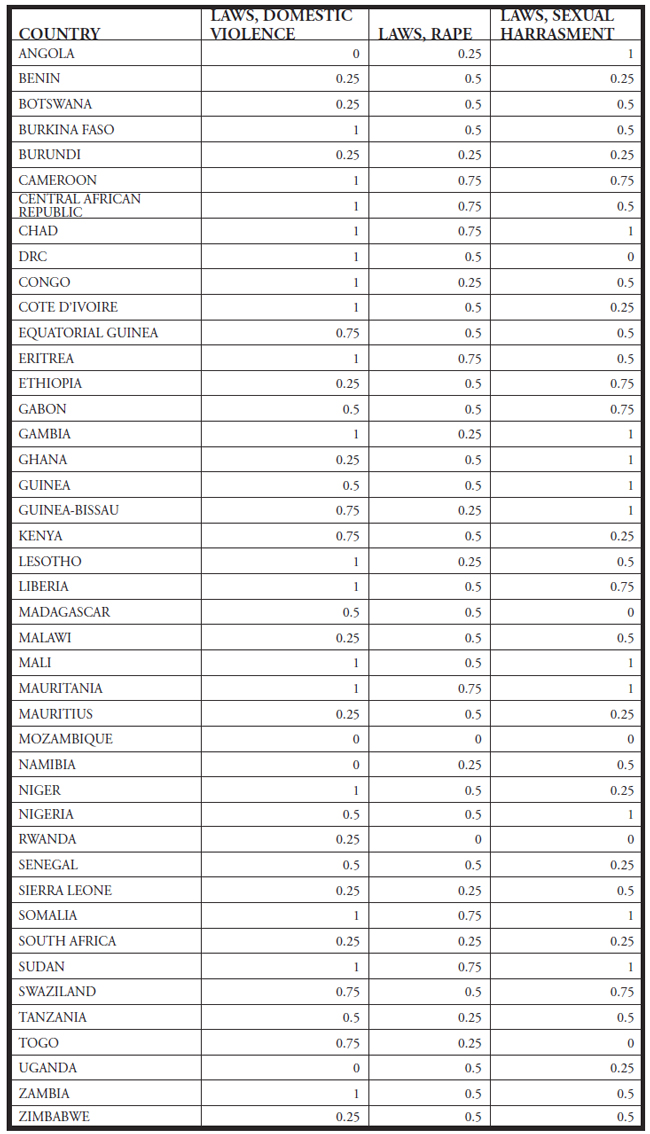

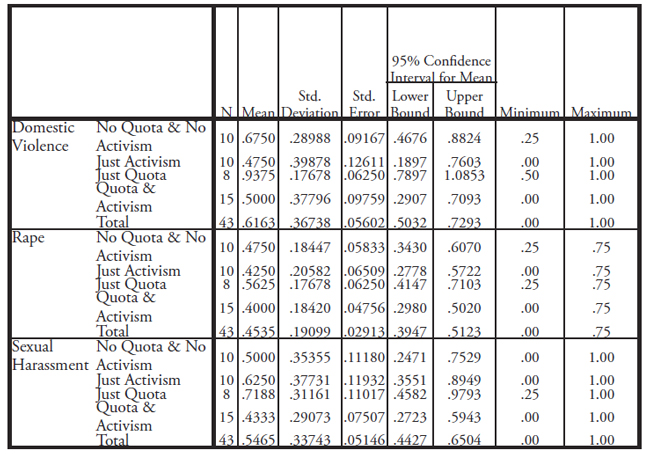

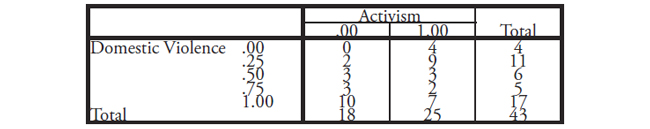

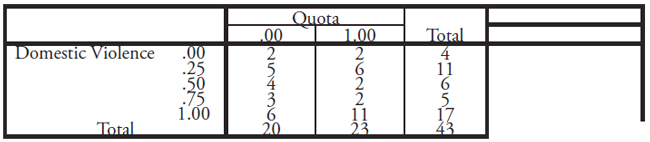

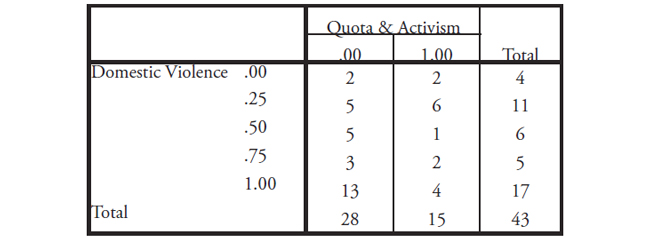

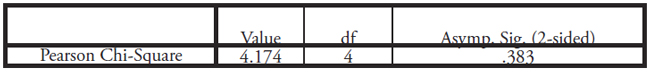

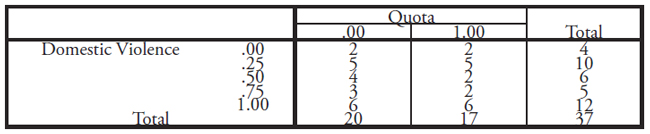

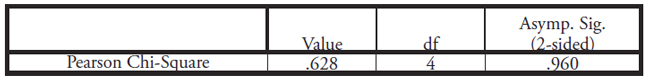

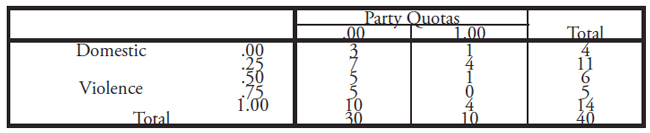

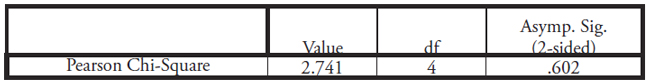

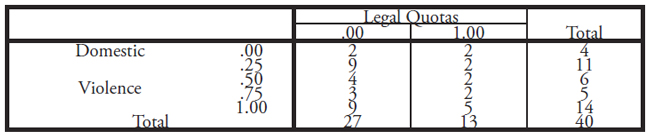

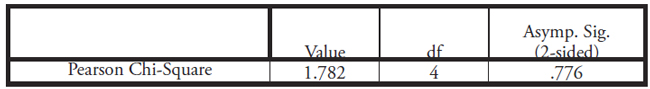

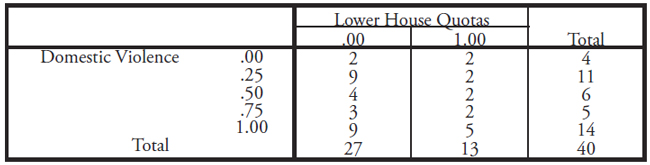

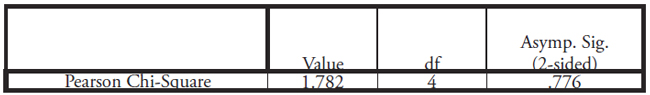

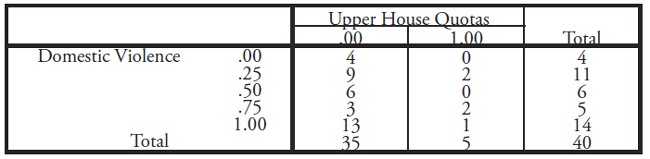

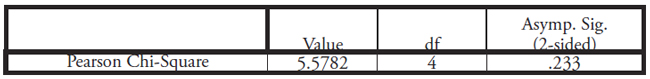

AppendixI. List of AcronymsII. FiguresFigure I: This figure depicts the national gender machinery currently present in the South African Government. FOSAD is the Forum of South Africa Directors-General. JMC on IQLSW is referenced in this paper merely as the JMC. III. Tables and GraphsTable I: This table indicates the placement of all 43 Sub-Saharan countries in the database into one of four categories based on the independent variables of quota implementation and female activism. Table II: This table displays the 2014 domestic violence, rape, and sexual harassment legislation scores for the 43 Sub Saharan-African countries in the dataset, as collected by the Social Institutions and Gender Index. Table III: This table identifies the descriptive statistics of domestic violence, rape, and sexual harassment scores for each of the four groups in the dataset. Table IV: This table displays the results of the One-Way Anova test. The difference in the domestic violence legislation score between the four groups of countries in the dataset is statistically significant (p-value =.019). Table V: This table displays the results of the Bonferonni Multiple Comparisons test. The difference in means between the Activism & Quota group and the Just Quota group is statistically significant (p-value = .030). Table VI: This table displays the Paired Samples Statistics between domestic violence and rape legislation scores for the 43 Sub-Saharan African countries in the database. Table VII: This table displays the Paired Samples T-Test between domestic violence and rape legislation scores for the 43 Sub-Saharan African countries in the database. The difference in means between rape and domestic violence scores is significant (p-value =.002). Table XI: This table displays the Chi-Squared Test between Quota and Domestic Violence as displayed in Table X above. p-value = .694 and is not statistically significant.Table XIII: This table displays the Chi-Squared Test between Quota & Activism and Domestic Violence as displayed in Table XII above. p-value = .383 and is not statistically significant. Table XIV: This table displays the Domestic Violence * Quota Cross tabulation counts after dropping Sudan, Somalia, Botswana, Eritrea, DRC, and Cote d'Ivoire from the dataset. Table XV: This table displays the Chi-Squared Test between Quota and Domestic Violence as displayed in Table XIV above, after dropping 6 cases. p-value = .960 and is not statistically significant. Table XVI: This table displays the Domestic Violence * Party Quotas Cross tabulation counts after dropping Sudan, Somalia, and Eritrea from the dataset. Table XVII: This table displays the Chi-Squared Test between Party Quotas and Domestic Violence as displayed in Table XVI above, after dropping 3 cases. p-value = .602 and is not statistically significant. Table XVIII: This table displays the Domestic Violence * Legal Quotas Cross tabulation counts after dropping Sudan, Somalia, and Eritrea from the dataset. Table XIX: This table displays the Chi-Squared Test between Legal Quotas and Domestic Violence as displayed in Table XVIII above, after dropping 3 cases. p-value = .776 and is not statistically significant. Table XX: This table displays the Domestic Violence * Lower House Quotas Cross tabulation counts after dropping Sudan, Somalia, and Eritrea from the dataset. Table XXI: This table displays the Chi-Squared Test between Lower House Quotas and Domestic Violence as displayed in Table XX above, after dropping 3 cases. p-value = .776 and is not statistically significant. Table XXII: This table displays the Domestic Violence * Upper House Quotas Cross tabulation counts after dropping Sudan, Somalia, and Eritrea from the dataset. Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in Women's & Gender Studies |