|

Featured Article: Roosevelt's Recession: A Historical and Econometric Examination of the Roots of the 1937 Recession

Similar to their treatment of the causes of the Great Depression, Friedman and Schwartz attribute the Recession to the Federal Reserve’s increase of reserve requirements in August 1936, March 1937, and May 1937. They believe that the nine-month, three-step doubling of reserve requirements, reaching the maximum level permitted, was the main cause of the Recession because it led to a contraction in the money supply, due to less bank lending.

Friedman and Schwartz begin their analysis of the 1937 time period by examining what role the discount rate played in decisions and outcomes that would later follow. They argue that the discount rate during the years leading up to the Recession, although low in absolute terms, was high relative to market rates, leading banks to view discounting as an expensive way to meet temporary liquidity needs. Therefore, banks relied on alternative sources for liquidity, like accumulating unusually large reserves. However, Friedman and Schwartz do not believe that the discount rate was a mistaken policy decision, “but only that it cannot be regarded as having contributed to monetary ‘ease.’”

According to their analysis, the singular mistake made by the Federal Reserve was one of interpretation. The Federal Reserve mistakenly interpreted the accumulation of excess reserves as a choice to hoard by risk-averse banks, not as a useful accumulation of reserves to be utilized as an alternative to discounting. Based on analysis of memoranda and statements among Federal Reserve officials, Friedman and Schwartz conclude that the prevailing view within the institution was “that excess reserves were idle funds servicing little economic function and reflecting simply absence of demand for loans.” The same memorandum outlines five major concerns arising over the size of excess reserves, like banking sector over-investment in government bonds, rapid over-borrowing by individuals and organizations due to the amount of money available for use, and possible inflationary pressures. Clearly, excess reserves were viewed as a problem that required a solution.

To counter the perceived negative effects of excess accumulation, the Federal Reserve had three tools available: open market operations, the act of selling or purchasing government bonds on the open market, adjusting the discount rate, and adjusting the reserve requirement. In an internal memorandum dated December 13, 1935, the Federal Reserve deemed open market operations inefficient due to the size of the excess reserves. Additionally, they ruled discount rate adjustments ineffective, given the public’s low demand for loans. Therefore, the tool of choice was increasing reserve requirements to immobilize the accumulated reserves from being used. Their hypothesis regarding the cause of the Recession links the increase in reserve requirements to a reduction in the money supply, due to the banking sector’s desire to hold excess reserves.

Friedman and Schwartz’s monumental volume brought the role of monetary policy into the spotlight, but their work of economic history largely lacks quantitative analysisand relies heavily on casual arguments. To further examine claims made by Friedman and Schwartz, specifically those related to 1937, a paper from 1992 is examined: Christina Romer’s “What Ended the Great Depression?” Although Romer builds on the foundation laid by Friedman and Schwartz, her paper is primarily concerned with the onset of recovery. She notes that Friedman and Schwartz “appear to have been more interested in the role that Federal Reserve inaction played in causing and prolonging the Great Depression than they were in quantifying the importance of monetary expansion in generating recovery." Her paper concludes that, primarily, the expansion of the money supply led to recovery. This conclusion is a mirror image of Friedman and Schwartz’s view that a decline in the money supply led to the 1937 downturn.

Early in her paper, Romer criticized contemporary Depression-related research for blindly adhering to assumptions off conclusions reached by leading economists from previous decades, like E. Cary Brown and Friedman. She says, “The emphasis that these early studies placed on policy inaction and ineffectiveness may have led the authors of more recent studies to assume that conventional aggregate-demand stimulus could not have influenced recovery”

Romer’s critique hints that contemporary economists may have misinterpreted relevant causes of recovery due to their preexisting assumptions. To aid her critique, Romer pointed to a paper by Bernanke and Parkinson. The two authors were surprised by the strength of overall recovery in the 1930’s, but having preemptively assumed the ineffectiveness of New Deal policy and not being interested in examining this assumption due to the narrow scope of their paper, the authors concluded that recovery came about naturally. Romer also discounts a specific assumption made by many contemporary economists. Whereas it is often assumed that recovery from the Depression was slow until the start of World War II, Romer bases her study on the assumption that recovery was strong. She contends that the decade-long recovery process was to be expected given the unprecedented magnitude of the early 1930’s and 1937 contraction. Romer concludes that without aggregate demand stimulus, which in her view took the form mainly of monetary expansion, “the economy would have remained depressed far longer and far more deeply than it actually did.”

Much of the literature regarding the 1937 Recession points to monetary policy decisions as the cause. Perhaps due to increasing ideological divisions or perhaps due to the continued taboo around fiscal stimulus, it is sometimes assumed that the support of monetary policy as a causal factor is equivalent to the discounting of the role that was or could have been played by fiscal policy. In an address in 2009, as a member of the White House’s Council of Economic Advisers, Romer clarified this point when she flatly stated:

I wrote a paper in 1992 that said that fiscal policy was not the key engine of recovery in the Depression. From this, some have concluded that I do not believe fiscal policy can work today or could have worked in the 1930s. Nothing could be farther than the truth.

Although monetary policy may have been the direct contributing factor that caused the 1937 Recession, it’s important to contextualize this cause in the absence of fiscal policy. Monetary policy decisions affected the economy at a time when the government pulled back spending. If one assumes that monetary policy was the only cause of the Recession, the next question to be asked is the following: would monetary policy decisions have had an impact if government spending had been maintained at early New Deal levels?

E. Cary Brown, an economist who taught at MIT for nearly sixty years, made a fundamental contribution to the study of the Recession by examining the question posed above. In his seminal 1956 paper, Brown argued that “fiscal policy seems to have been an unsuccessful recovery device,” but he added the caveat "not because it did not work, but because it was not tried.” Romer declared in her 2009 speech that the "crucial lesson from the 1930s is that a small fiscal expansion has only small effects."She reiterated Brown’s famous conclusion: “The key fact is that while Roosevelt's fiscal actions were a bold break from the past, they were nevertheless small relative to the size of the problem.” To contextualize her argument, Romer presented her audience with two figures: when Roosevelt took office in 1933, GDP was 30% below trend and one year later, in 1934, deficit spending rose only by 1.5% of GDP.

To consider the validity of Brown’s and Romer's statements, it must first be asked whether fiscal policy had an impact on the economy in 1937. Disregarding papers on both extremes of the spectrum, the consensus in the middle is that both monetary and fiscal policy factors had an impact on the 1937 downturn. In a paper about the Recession, Velde used a VAR model and concluded "monetary and fiscal factors account fairly well for the pattern of industrial production and, in particular, for the depth of the recession.”

Velde was concerned primarily with the hypothesized causes the Recession. His brief but targeted analysis shed light on this little-studied downturn by reaching a conclusion that shows both monetary and fiscal policy factors played contributing roles. However, one of the most important contributions provided by his study is not his conclusion, but instead his treatment of the monetary policy question. In regards to the impact that reserve requirement increases had on the money supply, Velde tried to resolve arguments put forward on one end by Friedman and Romer and on the other Telser.

Whereas Friedman argued that reserve requirements had a direct impact on the money supply through decreased lending, Telser examined both sides of the banking sector’s balance sheet and argued that banks responded to the reserve requirement increases not by decreasing lending, but instead by liquidating other assets to fulfill their desire for cushioned reserves. If Telser’s argument is assumed to be true, then lending did not decrease, and the reserve requirement increases had no impact on the money supply; therefore, the Recession could have only been caused by other hypothesized factors, of which only fiscal policy changes and wage increases remain. Friedman’s and Telser’s views are mutually exclusive, and they must be reconciled prior to a quantitative analysis, so that a fitting money supply variable, should one exist, can be compiled.

Velde’s findings are partially in agreement with Telser’s conclusion and partially in agreement with Friedman’s. Velde finds that banks did not respond to the increases by decreasing private lending for some time. In agreement with Telser, Velde said, "Looking at interest rates confirms that the impact of reserve requirements manifested itself on tradable securities rather than loans.” Velde continued to note that even after the first increase in August 1936, interest "rates charged by banks on loans were little affected.” Although his study so far has been in agreement with Telser, Velde went farther and examined even more deeply the possible mechanism by which the reserve ratio increases could have had a downward pressure on the money supply. He found that after the second increasein March 1937,the U.S. bond market, which had remained relatively stable, saw a spike in yield rates. The spike in the bond market took Morgenthau by surprise. According to Velde, the spike prompted Morgenthau to telephone and complain to Eccles, the Chairman of the Federal Reserve, that the Federal Reserve “bungled the increase in reserve requirements.”

Based on Velde’s analysis, Friedman was wrong in assuming a direct mechanism of impact on the money supply. Furthermore, Telser’s analysis was valid, but he was wrong to fully discount the role of reserve requirement increases without examining the other possible mechanisms of action. Velde concluded that given the bond rate increases and the sharp decline in corporate issues, the banking sector's demand for corporate and government liabilities had declined. The decreased demand likely was the indirect mechanism through which the reserve requirement increases impacted the economy. Velde noted, "The fall in lending translated into higher interest rates and a lower volume of issues.”

A 2006 paper published by economists Thomas Cargill and Thomas Mayer further discounts Telser’s conclusion. Cargill and Mayer examined more closely the effect of reserve requirement increases on the money supply. Given Telser’s surprising finding that conflicted with long-standing assumptions put forward by Friedman, Cargill and Mayer examined more closely the possible impact, if any, that the increased required reserves had on the money supply. They studied whether banks held reserves due to a lack of profitable lending opportunities, or whether banks hoarded reserves as a reactionary and precautionary measure. Because no reliable measurement of loan demand was available for the time period in question, Cargill and Mayer compared the reserve accumulation behavior of Federal Reserve member banks to that of non-member banks, which were not subject to Federal Reserve mandates:

If member banks increased their total reserve ratios because of a decline in the demand for bank credit, then on the reasonable assumption that there was no concurrent change in the relative volume of credit demand from member and nonmember banks, the total reserve and loan ratios of member banks and nonmember banks should have behaved in the same way when member bank reserve requirements where raised.

The authors utilized a regression analysis that examined the difference between member and non-member banks response behaviors to the increased reserve requirementsthat affected only the member banks. The overwhelmingly significant results are reported in Table 2 of their paper.

They concluded that banks did not respond “to the changes in reserve requirements essentially by changing theirexcess reserves.” Instead, Cargill and Mayer found that “member banks met a substantial part of their increased reserve requirements by reducing their earning assets.” Member banks, in response to the increased reserve requirements, liquidated assets in order to maintain a buffer of excess reserves similar to that which they had prior to the increases. Although the mechanism of action is in question, most of the recent literature is in agreement: the reserve requirement increases affected the money supply. Therefore, a money supply variable focused on the role of reserve requirement increases is necessary for a quantitative analysis.

Having pointed to studies that underscore the likely impact of fiscal policy and having argued that no matter the mechanism of action considered, reserve requirement increases likely had an impact on the money supply, focus will be turned in the next section to synthesizing the arguments put forward in an econometric study of only the 1937 Recession. The vast literature concerned with the debate over the role of monetary and fiscal policy is of little use to this study because the literature is primarily concerned with the time period as a whole (1929-1939) or the post-1939 war spending. Given the unique factors leading to the 1937 Recession, studies of the broader time period contribute little to an understanding of only this recession. These studies gloss over the 1937 Recession by treating the recovery period through WWII as one continuous progression. However, as shown earlier in Figure 2, the economy had reached an acceptable level of recovery by 1936, when industrial production matched its 1929 peak. Although unemployment was still high and the economy still in a delicate state, the country was inching towards full recovery until the Recession hit. The consolidation of the time period as one group is a questionable practice. Studies of the Depression should consider the 1929-1936, 1937-1938, and 1939-1945 time periods as distinct points of recovery given the unique factors affecting society within each period.Continued on Next Page »

An Act to Diminish the Causes of Labor Disputes Burdening or Obstructing Interstate and Foreign Commerce, to Create a National Labor Relations Board, and for Other Purposes., Pub. L. No. 74-198, Stat. (July 5, 1935). Accessed January 16, 2015. http://research.archives.gov/description/299843.

An act to provide adjusted compensation for veterans of the World War, and for other purposes., H.R. 10874, 67th Cong., 2d Sess. (1922).

Adjusted Compensation Payment Act, ch. 32, 49 Stat. 1099-1102 (Jan. 27, 1936).

Allen, William R. "Irving Fisher, F. D. R., and the Great Depression." History of Political Economy 9, no. 4 (1977): 560-87. http://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:hop:hopeec:v:9:y:1977:i:4:p:560-587.

Baker, Nancy. "Abel Meeropol (a.k.a. Lewis Allan): Political Commentator and Social Conscience." American Music 20, no. 1 (Spring 2002): 25-79.

Barber, William J. From New Era to New Deal: Herbert Hoover, the Economists, and American Economic Policy, 1921-1933. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

Black, Conrad. Franklin Delano Roosevelt: Champion of Freedom. New York: Public Affairs, 2003.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US), Industrial Production Index[INDPRO], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/INDPRO/, April 4, 2015.

Brown, E. Cary. "Fiscal Policy in the 'Thirties: A Reappraisal." The American Economic Review 46, no. 5 (December 1956): 857-79.

The Brownsville Herald (Brownsville, TX). "Prices." April 2, 1937, 1.

The Brownsville Herald (Brownsville, TX). "Public Funds Will Control High Prices?" April 4, 1937, 1-2.

Burns, Arthur F., and Wesley C. Mitchell. Measuring Business Cycles. Studies in Business Cycles 2. New York: National Bureau of Economic Research, 1946.

Cargill, Thomas F., and Thomas Mayer. "The Effect of Changes in Reserve Requirements during the 1930s: The Evidence from Nonmember Banks." The Journal of Economic History 66, no. 2 (June 2006): 417-32.

Cole, Harold L., and Lee E. Ohanian. "New Deal Policies and the Persistence of the Great Depression: A General Equilibrium Analysis." Journal of Political Economy 112, no. 4 (August 2004): 779-816. Accessed January 16, 2015. doi:10.1086/421169.

Complete Set of Speech Drafts. Volume 97: November 10, 1937. Diaries of Henry Morgenthau, Jr. Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum, Hyde Park, NY.

Conference to Talk Over Plans, 9/13/37. Volume 95: November 10, 1937; Page 1. Diaries of Henry Morgenthau, Jr. Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum, Hyde Park, NY.

"Document 50: February 28, 1938, Letter with Attachments, To: Keynes From: Roosevelt." In FDR's Response to Recession, edited by George McJimsey, 303-12. Vol. 26 of Documentary History of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidency. N.p.: University Publications of America, 2005.

Draft Letter to FDR. November 3, 1937. Volume 94: November 1-November 10, 1937; Page 47. The Diaries of Henry Morgenthau, Jr. Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum, Hyde Park, NY.

Dutcher, Rodney. "Behind the Scenes in Washington." The Brownsville Herald (Brownsville, TX), April 2, 1937, 4.

Edsforth, Ronald. The New Deal: America's Response to the Great Depression. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 2000.

Eggertsson, Gauti B. Great Expectations and the End of the Depression. Staff Report no. 234. N.p.: Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 2005.

———. "Great Expectations and the End of the Depression." American Economic Review 98, no. 4 (September 2008): 1476-516. doi:10.1257/aer.98.4.1476.

Eggertsson, Gauti B., and Benjamin Pugsley. "The Mistake of 1937: A General Equilibrium Analysis." Monetary and Economic Studies 24, nos. S-1 (December 2006): 151-90.

Eichengreen, Barry. "The U.S. Capital Market and Foreign Lending, 1920–1955." In Developing Country Debt and Economic Performance: The International Financial System, by Susan Margaret Collins and Jeffrey Sachs, 107-56. Vol. 1. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989. Previously published as "Til Debt Do Us Part: The U.S. Capital Market and Foreign Lending, 1920-1955." NBER Working Paper W2394. http://www.nber.org/chapters/c8988.

"FDR: From Budget Balancer to Keynesian, A President's Evolving Approach to Fiscal Policy in Times of Crisis." Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum. http://www.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/aboutfdr/budget.html.

Federal Reserve Board. Tenth Annual Report of the Federal Reserve Board: Covering Operations for the Year 1923. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1924. Accessed November 23, 2014. https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/docs/publications/arfr/1920s/arfr_1923.pdf.

Fisher, Irving. Booms and Depressions: Some First Principles. New York: Adelphi, 1932.

———. "The Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions." Econometrica 1, no. 4 (October 1933): 337-57. DOI:10.2307/1907327.

———. "Dollar Stabilization." In Encyclopedia Britannica, 852-53. Vol. XXX. http://www.econlib.org/library/Essays/fshEnc1.html.

———. "Mathematical Investigations in the Theory of Value and Prices." Transactions of the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences 9 (1892): 1-124.

———. "Our Unstable Dollar and the So-Called Business Cycle." Journal of the American Statistical Association 20, no. 150 (June 1925): 179-202. doi:10.2307/2277113.

———. "Stabilizing Price Levels." The New York Times, September 2, 1923, sec. XX, 10.

———. "Why Has the Doctrine of Laissez Faire Been Abandoned?" Science, n.s., 25, no. 627 (January 4, 1907): 18-27. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1633692.

Friedman, Milton, Paul A. Samuelson, and Henry Wallich. "How the Slump Looks to Three Experts." Newsweek, May 25, 1970, 78-79. Accessed November 23, 2014. http://hoohila.stanford.edu/friedman/newsweek.php.

Friedman, Milton, and Anna Jacobson Schwartz. A Monetary History of the United States 1867-1960. 9th ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993.

Gordon, Robert J., and Robert Krenn. "New Gordon-Krenn quarterly and monthly data set for 1913-54." Unpublished raw data, Northwestern University, n.d. Accessed March 30, 2015. http://faculty-web.at.northwestern.edu/economics/Gordon/researchhome.html.

Hearings Before the Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs (2009) (statement of Lee E. Ohanian). Accessed January 25, 2015. http://www.banking.senate.gov/public/index.cfm?FuseAction=Files.View&FileStore_id=6cce4fbb-e7cd-4699-8892-9c5d1285e871.

Hemingway, Ernest. "Who Murdered the Vets?" The New Masses, September 17, 1935, 9-10. Accessed March 10, 2015. http://www.unz.org/Pub/NewMasses-1935sep17-00009.

Hobsbawm, E. J. Industry and Empire: The Birth of the Industrial Revolution. Edited by Chris Wrigley. New York: New Press, 1999. Originally published as Industry and Empire: An Economic History of Britain Since 1750 (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1968).

Jones & Laughlin Steel Corp. v. NLRB, 301 U.S. (1937). Accessed January 16, 2015. https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/301/1/case.html.

Kahn, Richard. "The Relation of Home Investment to Unemployment." The Economic Journal 41, no. 162 (June 1931): 173-98.

Keynes, John Maynard. "Chapter 24: Concluding Notes on the Social Philosophy towards Which the General Theory Might Lead." In The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money.

———. "The Great Slump of 1930." The Nation and Athenaeum 48 (December 20, 1930): 402.

———. "The Great Slump of 1930 II." The Nation and Athenaeum 48 (December 27, 1930): 427-28.

———. A Tract on Monetary Reform. 1923. Reprint, London: Macmillan, 1924.

Kindleberger, Charles Poor. The World in Depression, 1929-1939. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973.

May, Dean L. From New Deal to New Economics: The Liberal Response to the Recession. Edited by Frank Freidel. Modern American History. New York: Garland Publishing, 1981.

Mehrotra, Ajay K. "Edwin R.A. Seligman and the Beginnings of the U.S. Income Tax." Tax Notes, November 14, 2005, 933-50.

Nasar, Sylvia. Grand Pursuit: The Story of Economic Genius. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011.

NBER. The End of the Great Depression 1939-41: Policy Contributions and Fiscal Multipliers. By Robert J. Gordon and Robert Krenn. Working Paper no. 16380. 2010. Accessed March 30, 2015. doi:10.3386/w16380.

The New York Times. "Bonus Bill Becomes Law." January 28, 1936, Late City edition, 1. Accessed March 8, 2015. http://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1936/01/28/87903226.html?pageNumber=1.

The New York Times. "Both Coasts Threatened." September 3, 1935, Late City edition, 1. Accessed March 8, 2015. http://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1935/09/03/issue.html.

The New York Times. "Fisher Sees Stocks Permanently High." October 16, 1929, 8.

The New York Times. "Link Bonus Issue to Florida Deaths." September 15, 1935, Late City edition, N6. Accessed March 8, 2015. http://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1935/09/15/93707816.html?pageNumber=99.

The New York Times. "The Stock Market." October 20, 1937, Late City edition, 22. Accessed March 8, 2015. http://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1937/10/20/103216107.html?pageNumber=22.

The New York Times. "Veteran's Camp Wrecked by Storm." September 4, 1935, Late City edition, 1. Accessed March 8, 2015. http://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1935/09/04/93481928.html.

The New York Times. "Veterans Lead Fatalities. Only 11 of 192 Reported as Left Alive in One Florida Camp." September 5, 1935, Late City edition, 1. Accessed March 8, 2015. http://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1935/09/05/93482496.html?pageNumber=1.

Office of the Secretary of the Senate, Presidential Vetoes, 1789-1988, S. Doc. No. 102-12 (1992). Accessed March 8, 2015. http://www.senate.gov/reference/resources/pdf/presvetoes17891988.pdf.

"131 'I Pledge You—I Pledge Myself to a New Deal for the American People.' the Governor Accepts the Nomination for the Presidency, Chicago, Ill. July 2, 1932." In The Genesis of the New Deal, 1928-1932, 647-58. Vol. 1 of The Public Papers and Addresses of Franklin D. Roosevelt. New York: Random House, 1938.

Papadimitriou, Dimitri B., and Greg Hannsgen. Lessons from the New Deal: Did the New Deal Prolong or Worsen the Great Depression? Working Paper no. 581. Annandale-on-Hudson, NY: Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, 2009.

Personal Memo. October 19, 1937. Volume 92: October 12-October 19, 1937; Page 229. The Diaries of Henry Morgenthau, Jr. Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum, Hyde Park, NY.

"Press Conference #425-15." January 14, 1938. Press Conferences of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1933-1945. Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum, Hyde Park, NY.

"Press Conference #434." February 15, 1938. Press Conferences of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1933-1945. Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum.

Press Conference #401-1. October 8, 1937. Press Conferences of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1933-1945. Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum, Hyde Park, NY.

"Press Conference #405-5." October 22, 1937. Press Conferences of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1933-1945. Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum, Hyde Park, NY.

"Press Conference #409-7." November 9, 1937. Press Conferences of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1933-1945. Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum, Hyde Park, NY.

"Press Conference #415-8." December 10, 1937. Press Conferences of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1933-1945. Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum, Hyde Park, NY.

"Press Conference #416-4." December 14, 1937. Press Conferences of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1933-1945. Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum, Hyde Park, NY.

"Press Conference #357." April 2, 1937. Page 239. Press Conferences of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1933-1945. Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum.

Romer, Christina D. "Lessons from the Great Depression for Economic Recovery in 2009." Speech presented at Brookings Institution, Washington D.C., March 9, 2009. Accessed April 21, 2015. http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/events/2009/3/09-lessons/0309_lessons_romer.pdf.

———. "Spurious Volatility in Historical Unemployment Data." Journal of Political Economy 94, no. 1 (February 1986): 1-37. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1831958.

———. "What Ended the Great Depression?" The Journal of Economic History 52, no. 4 (December 1992): 757-84.

Roose, Kenneth D. The Economics of Recession and Revival: An Interpretation of 1937-38. Yale Studies in Economics 2. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1954.

———. "The Recession of 1937-38." Journal of Political Economy 56, no. 3 (June 1948): 239-48. Accessed January 26, 2015. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1825772.

———. "The Role of Net Government Contribution to Income in the Recession and Revival of 1937-38." The Journal of Finance 6, no. 1 (March 1951): 1-18. DOI:10.1111/j.1540-6261.1951.tb04437.x.

Roosevelt, Franklin D. "Annual Budget Message to Congress." Address, January 7, 1937. The American Presidency Project. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=15337.

———. "Annual Message to Congress." Address, January 6, 1937. The American Presidency Project. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=15336.

———. "Fireside Chat on Banking." Speech, March 12, 1933. The American Presidency Project. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=14540.

———. "Message to Congress Recommending Legislation, November 5, 1937." The American Presidency Project. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=15496.

———. "Proclamation 2040 - Bank Holiday." The American Presidency Project. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=14485.

———. "Proclamation 2039 - Declaring Bank Holiday." The American Presidency Project. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=14661.

———. "60 - Message to Congress on Appropriations for Work Relief for 1938. April 20, 1937." The American Presidency Project. Accessed March 19, 2015. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=15393.

———. "Statement Summarizing the 1938 Budget, October 19, 1937." The American Presidency Project. Accessed March 22, 2015. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=15486.

Schumpeter, Joseph A. "Chapter 5.4: Unemployment and the ‘State of the Poor’." In History of Economic Analysis, 258-63. Edited by Elizabeth B. Schumpeter. New York: Oxford University Press, 1954.

Shlaes, Amity. The Forgotten Man: A New History of the Great Depression. New York: Harper Collins, 2007.

Smith, Adam. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Edited by Edwin Cannan. 5th ed. 1776. Reprint, London: Methuen & Co., 1904. http://www.econlib.org/library/Smith/smWN.html.

Telser, Lester G. "Higher Member Bank Reserve Ratios in 1936 and 1937 Did Not Cause the Relapse into Depression." Journal of Post Keynesian Economics 24, no. 2 (Winter 2001-2): 205-16.

———. "The Veterans' Bonus of 1936." Journal of Post Keynesian Economics 26, no. 2 (Winter 2003-4): 227-43.

Three Parts of Speech as Decided Upon, 10/28/37. Volume 95: November 10, 1937; Page 261. Diaries of Henry Morgenthau, Jr. Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum, Hyde Park, NY.

The Times-Picayune (New Orleans, LA). "A Cloud That's Dragonish." January 8, 1937, 12.

The Times-Picayune (New Orleans, LA). "Industry Pushes up after Holiday Lull; Steel Leads." January 11, 1937, 18.

Transcript of Call between Morgenthau and Burgess. October 19, 1937. Volume 92: October 12-October 19, 1937; Page 222. The Diaries of Henry Morgenthau, Jr. Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum, Hyde Park, NY.

Transcript of Phone Call between Morgenthau and FDR. October 20, 1937. Volume 93: October 20-October 31, 1937; Page 21. The Diaries of Henry Morgenthau, Jr. Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum, Hyde Park, NY.

United States Senate Special Committee on the Termination of the National Emergency. Emergency Powers Statutes: Provisions of Federal Law Now in Effect Delegating to the Executive Extraordinary Authority in Time of National Emergency. Report no. 93-549. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1973.

U.S. Department of Commerce Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce. Statistical Abstract of the United States 1934. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1934. Accessed November 23, 2014. https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/docs/publications/stat_abstract/1930s/sa_1934.pdf.

Velde, François. "The Recession of 1937—A Cautionary Tale." Economic Perspectives 33, no. 4 (2009): 16-37.

Wood, Howard. "Stocks Crash to New Lows; Selling Swamps Market; Blame Federal Policies." Chicago Daily Tribune, October 19, 1937, Final edition, 1. Accessed March 10, 2015. http://archives.chicagotribune.com/1937/10/19/page/1/article/stocks-crash-to-new-lows.

World War Adjusted Compensation Act, ch. 157, 43 Stat. 121-131 (May 19, 1924). Accessed March 7, 2015. http://www.loc.gov/law/help/statutes-at-large/68th-congress/c68.pdf.

Yale University. "Past Presidents." Office of the President. Accessed December 7, 2014. http://president.yale.edu/past-presidents.

Endnotes

- Real GDP is a measure of economic output that is adjusted for price changes at each observation year. The values in Figure 1 are in terms of 1937 dollars.

- The data was made relative to the pre-Depression peak in industrial production, which occurred in the year 1929. In other words, the data was adjusted so that the 1929 peak equals 100%.

- Barber, From New Era to New Deal, 118.

- Ibid.,195.

- Ibid., 36.

- Kindleberger, The World in Depression, 56.

- Eichengreen, "The U.S. Capital Market," in Developing Country Debt and Economic, 1:122.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 1:124.

- Barber, From New Era to New Deal, 72.

- Ibid., 73.

- U.S. Department of Commerce Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce, Statistical Abstract of the United, 279.

- According to data obtained from the BEA, GDP in 1929 was $104.6 Billion and 2014 Q2 GDP is $16,010 Billion.

- Federal Reserve Board, Tenth Annual Report of the Federal, 34.

- Friedman and Schwartz, A Monetary History of the United, 254.

- Fisher Sees Stocks Permanently High,” The New York Times, October 16, 1929.

- Friedman, Samuelson, and Wallich, "How the Slump Looks to Three Experts," Newsweek, May 25, 1970.

- The money supply refers to money available for use and circulating in the economy. Varying standardized measures of the money supply exist, from most liquid measurement of money to least liquid.

- Friedman and Schwartz, A Monetary History of the United, 300.

- Ibid., 308.

- Ibid., 310.

- Edsforth, The New Deal: America's, 43.

- Ibid., 40.

- Friedman and Schwartz, A Monetary History of the United, 313.

- Ibid., 315-317.

- Ibid., 322.

- Ibid., Table A-1, 713.

- Black, Franklin Delano Roosevelt: Champion, 269.

- Roosevelt, "Proclamation 2039 - Declaring," The American Presidency Project.

- Roosevelt, "Proclamation 2040 - Bank," The American Presidency Project.

- United States Senate Special Committee on the Termination of the National Emergency, Emergency Powers Statutes: Provisions, 4-5.

- Roosevelt, "Fireside Chat on Banking," The American Presidency Project.

- Friedman and Schwartz, A Monetary History of the United, 311.

- Ibid., 312.

- Hobsbawm, Industry and Empire: The Birth, 190.

- Say’s Law is the defunct notion that production is itself the source of demand. An individual producer is paid for their services and that payment is used to purchase other goods.

- Keynes, "The Great Slump of 1930," 402.

- Nasar, Grand Pursuit: The Story, 323.

- "131 'I Pledge You—I," in The Genesis of the New Deal, 651.

- Ibid., 652.

- Ibid., 658.

- Schumpeter, "Unemployment and the ‘State of the Poor’," inHistory of Economic Analysis.

- A concise history of Progressive-Era economic policy reform efforts, specifically that of public finance, is provided in: Ajay K. Mehrotra, "Edwin R.A. Seligman and the Beginnings of the U.S. Income Tax,"Tax Notes, November 14, 2005.

- Keynes, "The Great Slump of 1930," 402.

- Ibid.

- Keynes, "The Great Slump of 1930, II" 428.

- Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature, IV.2.9.

- Nasar, Grand Pursuit: The Story, 149.

- "Past Presidents," Office of the President.

- Nasar, Grand Pursuit: The Story, 150.

- Ibid., 151.

- Ibid.

- Fisher, "Why Has the Doctrine," 27.

- Nasar, Grand Pursuit: The Story, 283.

- Keynes, A Tract on Monetary, 187.

- Fisher, "Dollar Stabilization.," in Encyclopedia Britannica, XXX.

- Friedman and Schwartz, A Monetary History of the United, 206.

- Ibid., 226-233.

- Romer, "Spurious Volatility in Historical," 31.

- Nasar, Grand Pursuit: The Story, 301.

- Irving Fisher, "Stabilizing Price Levels," The New York Times, September 2, 1923.

- Fisher, "Our Unstable Dollar and the So-Called," 201.

- Fisher, "The Debt-Deflation Theory of Great," 342.

- Fisher, Booms and Depressions: Some, 142.

- Allen, "Irving Fisher, F. D. R., and the Great," 576.

- Ibid., 562.

- Ibid., 580-581.

- Ibid., 577.

- Ibid., 565.

- Ibid., 565.

- Fisher’s latter comment is in regards to the 17% increase in nominal wages between November 1936 and November 1937, as measured by the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the National Industrial Conference Board (Velde, "The Recession of 1937—A," 29).

- Nasar, Grand Pursuit: The Story, 319.

- Ibid., 326.

- Ibid., 324.

- Richard Kahn, "The Relation of Home Investment to Unemployment," The Economic Journal 41, no. 162 (June 1931)

- "FDR: From Budget Balancer to Keynesian,” Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum, http://www.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/aboutfdr/budget.html.

- Kindleberger, The World in Depression, 262.

- An act to provide adjusted compensation for veterans of the World War, and for other purposes., H.R. 10874, 67th Cong., 2d Sess. (1922). Office of the Secretary of the Senate, Presidential Vetoes, 1789-1988, S. Doc. No. 102-12 (1992), 225.

- Ibid., 228.

- World War Adjusted Compensation Act, ch. 157, 43 Stat. 121-131 (May 19, 1924).

- "Both Coasts Threatened," The New York Times, September 3, 1935.

- "Veteran's Camp Wrecked by Storm," The New York Times, September 4, 1935.

- "Veterans Lead Fatalities,” The New York Times, September 5, 1935.

- "Link Bonus Issue to Florida Deaths," The New York Times, September 15, 1935.

- Nancy Baker, "Abel Meeropol (a.k.a. Lewis Allan): Political Commentator and Social Conscience," American Music 20, no. 1 (Spring 2002): 45.

- Hemingway, "Who Murdered the Vets?," The New Masses, September 17, 1935.

- Adjusted Compensation Payment Act, ch. 32, 49 Stat. 1099-1102 (Jan. 27, 1936).

- "Bonus Bill Becomes Law," The New York Times, January 28, 1936.

- For a detailed analysis of the Soldier’s Bonus expansionary effect, consult: Telser, "The Veterans' Bonus of 1936,"Journal of Post Keynesian Economics26, no. 2 (Winter 2003-4).

- Eggertsson and Pugsley, "The Mistake of 1937," 174.

- Roosevelt, "Annual Message to Congress, January 6, 1937,” The American Presidency Project.

- Roosevelt, "Annual Budget Message to Congress," The American Presidency Project.

- "Press Conference #357," April 2, 1937, Page 239, Press Conferences of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1933-1945, Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum.

- Data source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US), Industrial Production Index[INDPRO], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

- "The Stock Market," The New York Times, October 20, 1937.

- Howard Wood, "Stocks Crash to New Lows,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 19, 1937.

- "The Stock Market," The New York Times, October 20, 1937.

- Personal Memo, October 19, 1937, Volume 92: October 12-October 19, 1937; Page 229, The Diaries of Henry Morgenthau, Jr., Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum, Hyde Park, NY.

- Transcript of Call between Morgenthau and FDR. October 19, 1937, Volume 92: October 12-October 19, 1937; Page 230, The Diaries of Henry Morgenthau, Jr., Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum, Hyde Park, NY.

- Transcript of Call between Morgenthau and Burgess, October 19, 1937, Volume 92: October 12-October 19, 1937; Page 222, The Diaries of Henry Morgenthau, Jr., Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum, Hyde Park, NY.

- Transcript of Phone Call between Morgenthau and FDR, October 20, 1937, Volume 93: October 20-October 31, 1937; Page 21, The Diaries of Henry Morgenthau, Jr., Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum, Hyde Park, NY.

- Draft Letter to FDR, November 3, 1937, Volume 94: November 1-November 10, 1937; Page 47, The Diaries of Henry Morgenthau, Jr., Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum, Hyde Park, NY.

- Roosevelt, "60 - Message to Congress," The American Presidency Project.

- Press Conference #401-1.

- Press Conference #405-5.

- Roosevelt, "Statement Summarizing the 1938," The American Presidency Project.

- Press Conferences #409-7; #415-8; #416-4.

- Press Conference #425-15.

- "A Cloud That's Dragonish,"The Times-Picayune(New Orleans, LA), January 8, 1937, 12.

- "Industry Pushes up after Holiday Lull; Steel Leads,"The Times-Picayune(New Orleans, LA), January 11, 1937, 18.

- Rodney Dutcher, "Behind the Scenes in Washington,"The Brownsville Herald(Brownsville, TX), April 2, 1937,4.

- This small, local, newspaper featured during the same week at least two in-depth articles focused on analysis of policy, not only news: "Public Funds Will Control High Prices?,"The Brownsville Herald(Brownsville, TX), April 4, 1937,1-2. "Prices,"The Brownsville Herald(Brownsville, TX), April 2, 1937,1.

- Conference to Talk Over Plans, 9/13/37, Volume 95: November 10, 1937; Page 1, Diaries of Henry Morgenthau, Jr., Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum, Hyde Park, NY.

- Three Parts of Speech as Decided Upon, 10/28/37, Volume 95: November 10, 1937; Page 261, Diaries of Henry Morgenthau, Jr., Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum, Hyde Park, NY.

- Shlaes,The Forgotten Man: A New History, 341-342.

- Complete Set of Speech Drafts, Volume 97: November 10, 1937; Page 149, Diaries of Henry Morgenthau, Jr., Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum, Hyde Park, NY.

- Ibid., 142.

- Ibid., 143.

- Roosevelt, "Message to Congress Recommending," The American Presidency Project.

- "Document 50: February 28, 1938, Letter with attachments, To: Keynes From: Roosevelt," in FDR's Response to Recession, ed. George McJimsey, vol. 26, Documentary History of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidency (University Publications of America, 2005), 307.

- Ibid., 312.

- Roose, "The Recession of 1937-38," 239.

- Roose, "The Role of Net Government," 1.

- Personal Income is income received by individuals, non-profit institutions, private trust funds, and private pension funds. It is the sum of wages, labor income, rental income, interest, dividends, and transfer payments. Source: National Income and Product Statistics of the United States 1929-46, US Dept. of Commerce, 1946, p. 53-54. Net Gvt. Contribution to Income is a breakdown of measured net decreasing (taxes, etc.) and increasing expenditures (social services, etc.). Figures include local, state, and federal contributions. Source: Deficit Spending and the National Income, Henry H. Villard, 1941, Appendix I p. 323.

- Roose, "The Role of Net Government," 4.

- Ibid., 240.

- Ibid., 6.

- Ibid., 14.

- Roose, The Economics of Recession, 6.

- "Radio Address." Under the auspices of the National Radio Forum, conducted by The Washington Evening Star, broadcast over the National Broadcasting Company Network, January 23, 1939, https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/title/?id=446#!7658, accessed on February 1, 2015.

- Friedman and Schwartz, A Monetary History of the United, 493.

- Ibid., 495.

- Cole and Ohanian, "New Deal Policies and the Persistence," 783.

- Ibid., 784.

- An Act to Diminish the Causes of Labor Disputes Burdening or Obstructing Interstate and Foreign Commerce, to Create a National Labor Relations Board, and for Other Purposes., Pub. L. No. 74-198, Stat. (July 5, 1935).

- Jones & Laughlin Steel Corp. v. NLRB, 301 U.S. (1937).

- Cole and Ohanian, "New Deal Policies and the Persistence," 788.

- Velde, "The Recession of 1937—A," 30.

- Testimony Before the US Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs (2009) (statement of Lee E. Ohanian).

- Velde, "The Recession of 1937—A," 31.

- Romer, "What Ended the Great Depression?," 763.

- Overwhelmingly, the NLRA has been discounted as a contributing factor to the Recession. For a detailed review of the existing literature, specifically that related to the NLRA, consult: Papadimitriou and Hannsgen,Lessons from the New Deal: Did the New Deal Prolong or Worsen the Great Depression?

- Gauti B. Eggertsson and Benjamin Pugsley, "The Mistake of 1937: A General Equilibrium Analysis," Monetary and Economic Studies 24, nos. S-1 (December 2006): 153.

- Ibid., 151.

- Ibid., 154.

- Gauti B. Eggertsson, Great Expectations and the End of the Depression, staff report no. 234 (Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 2005). Published as "Great Expectations and the End of the Depression," American Economic Review 98, no. 4 (September 2008).

- Eggertsson and Pugsley, "The Mistake of 1937," 174.

- Franklin D. Roosevelt, "Annual Message to Congress," address, January 6, 1937, The American Presidency Project, http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=15336.

- Eggertsson and Pugsley, "The Mistake of 1937," 175, Table 3.

- Ibid., 182.

- Ibid., 180.

- "Press Conference #434," February 15, 1938, Press Conferences of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1933-1945, Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum.

- Friedman and Schwartz, A Monetary History of the United, 496.

- Arthur F. Burns and Wesley C. Mitchell, Measuring Business Cycles, Studies in Business Cycles 2 (New York: National Bureau of Economic Research, 1946),88-89

- Roose, "The Role of Net Government," 10.

- Friedman and Schwartz, A Monetary History of the United, 517.

- Ibid., 515.

- Ibid., 518.

- Each concern listed on the memorandum is closely analyzed in A Monetary History, 523.

- Ibid., 520.

- Romer, "What Ended the Great," 758.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 759.

- Ibid., 758.

- Romer, "Lessons from the Great Depression for Economic Recovery in 2009," speech presented at Brookings Institution, Washington D.C., March 9, 2009, 3.

- Brown, "Fiscal Policy in the 'Thirties," 863-866.

- Romer, "Lessons from the Great,” speech, 3.

- Ibid., 4.

- Velde, "The Recession of 1937—A," 34.

- Ibid., 25.

- Ibid., 26.

- Ibid.

- Cargill and Mayer, "The Effect of Changes," 417-418.

- Ibid., 430.

- Ibid., 430-431.

- January 1935 was chosen as the starting point because the economy was, by that time, in steady recovery. This allows for an analysis untarnished by the shocks that occurred early during the Depression. December 1938 was chosen as the end point in order to exclude from the analysis any possible impacts of pre-WWII German aggression, especially that caused by the Occupation of Czechoslovakia in March 1939.

- Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US), Industrial Production Index [INDPRO], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/INDPRO/

- NBER, The End of the Great Depression 1939-41: Policy Contributions and Fiscal Multipliers, by Robert J. Gordon and Robert Krenn, working paper no. 16380, 2010. Robert J. Gordon and Robert Krenn, "New Gordon-Krenn quarterly and monthly data set for 1913-54" (unpublished raw data), accessed March 30, 2015, http://faculty-web.at.northwestern.edu/economics/Gordon/researchhome.html.

- NBER, The End of the Great, 43. Gordon and Krenn provide more detailed information about the process, including the monthly independent interpolators used, in their appendix. (NBER, The End of the Great, 42-54).

- Gordon and Krenn explain the transformation of government spending: “A problem arises in this series because it includes not just G but also transfer payments, which are excluded when calculating GDP. The monthly interpolator series is distorted by particularly large transfer payments in scattered quarters. To find these quarters, we calculated the monthly log change in the interpolator, after changing the data to real terms and X11 s.a. Whenever a monthly change of +40 percent or more was followed by a monthly change of approximately the same amount with a negative sign, we replaced that “bulge” observation by the average of the preceding and succeeding months. These bulges occurred and were corrected for in 4 months: 1931:12, 1934:01, 1936:06, and 1937:06.” (NBER, The End of the Great, 46.)

- The wage and manhour datasets were individually re-indexed to January 1935 prior to their transformation.

- The assumption that monetary policy may have played a role in the recession hinges on the assumption that the money supply was impacted by the increased reserve requirements. Based on the related discussion presented in the previous chapter, both assumptions are made.

- NBER macrohistory datasets utilized: Total sum of excess and required reserves held, (series 14064); Percentage of total reserves held to reserves required (series 14086).

- Velde, "The Recession of 1937—A,"24.

- Velde’s Figure 8.C highlights the remarkably stark accumulation of excess reserves by central reserve city banks. (Velde, "The Recession of 1937—A,"24.)

- The monthly GDP deflator was obtained from the Gordon and Krenn dataset. See footnote 178.

- Real money supply excluding reserves was created by subtracting deflated total reserves (series 14064) from deflated money stock (series 14144a).

- A strong case has been made for the use of bank assets, not liabilities, as the measurement of bank holdings during the 1937 period. However, to examine closely the argument as made by Friedman, and due to the lack of reliable monthly asset-side data, the more traditional liability-side measurement is used. For a detailed study of the alternative asset-side measurement, one that highlights the shortcomings of liability-side measurements, consult: Telser, "Higher Member Bank Reserve Ratios in 1936 and 1937 Did Not Cause the Relapse into Depression,"Journal of Post Keynesian Economics.

- Model 4 was cleaned by removing, step by step, the most insignificant variable lags found in Model 2.Insignificant variables were removeduntil regression was narrowed to only significant regressors.

- G% of GDP during years examined averaged 15%.

- NBER, The End of the Great, 35.

- Keynes, "Chapter 24: Concluding Notes," in The General Theory of Employment.

Appendix

Tables

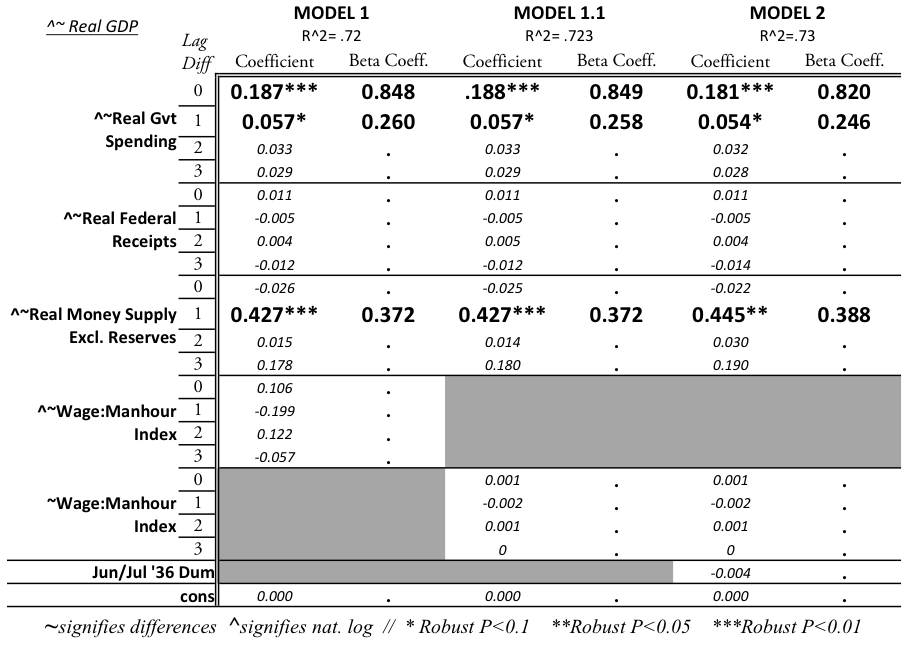

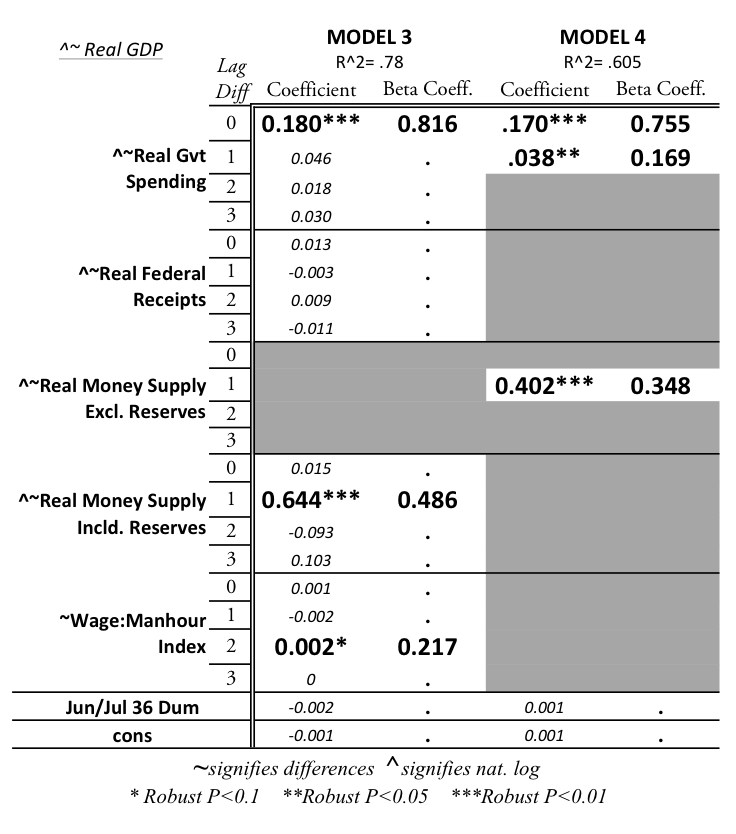

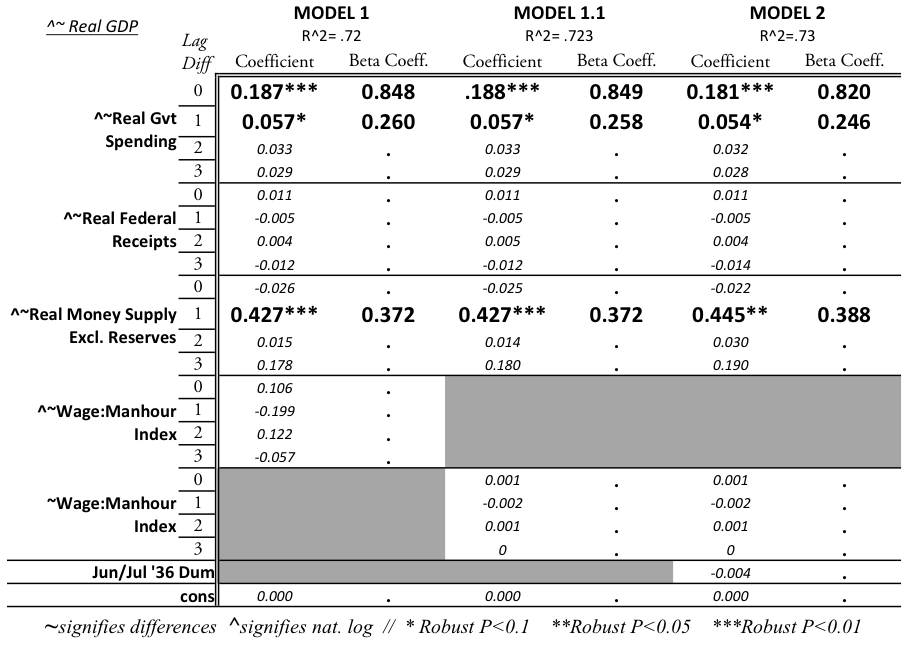

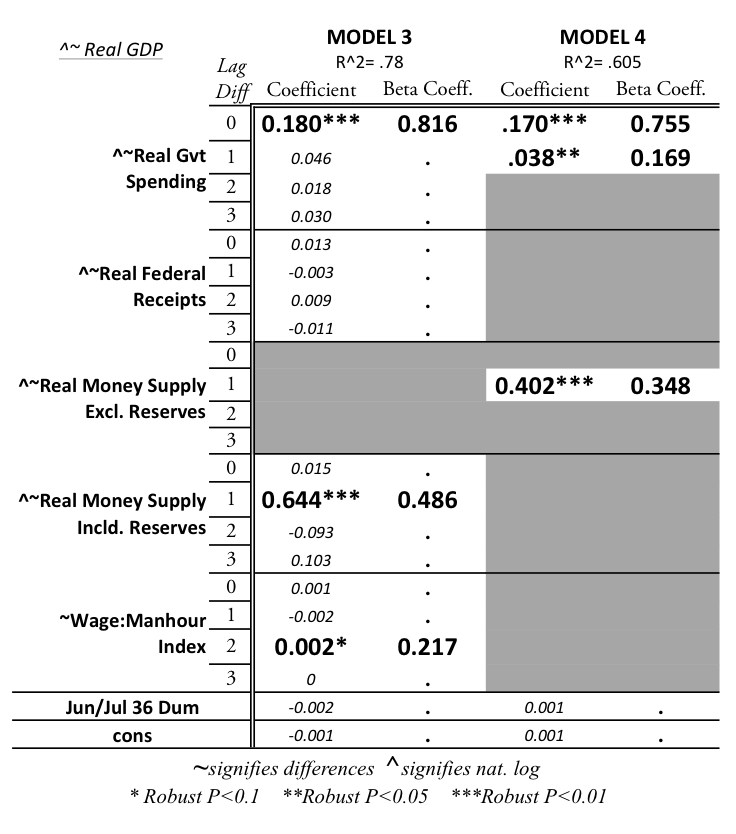

Table A-1

Table A-2

Table A-3

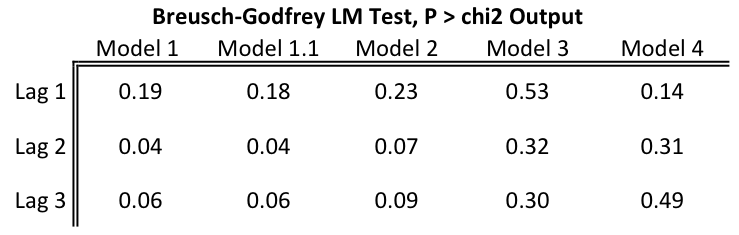

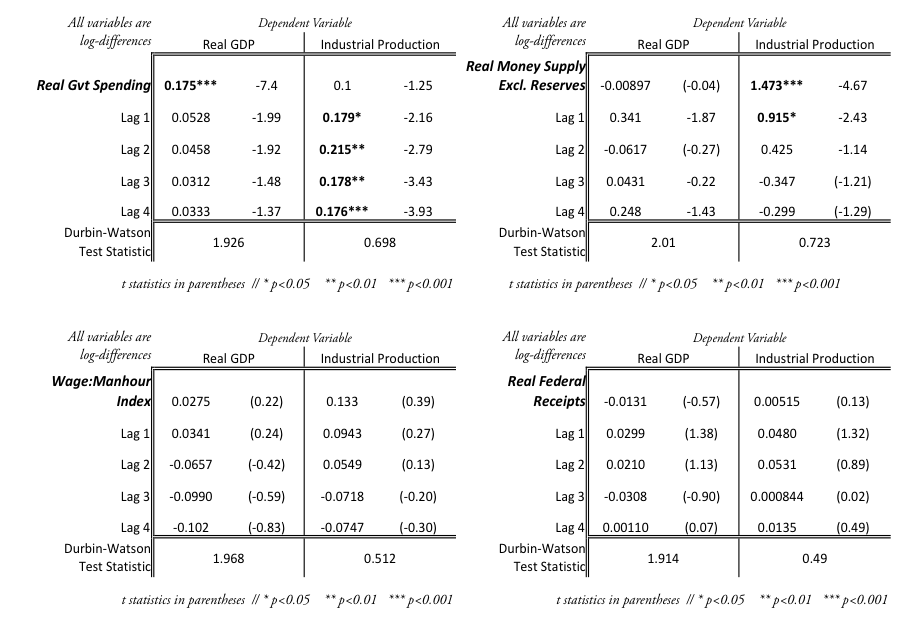

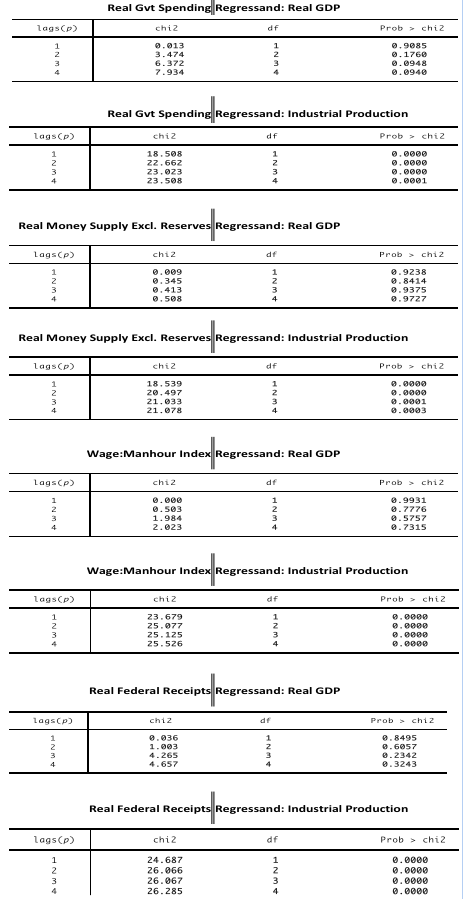

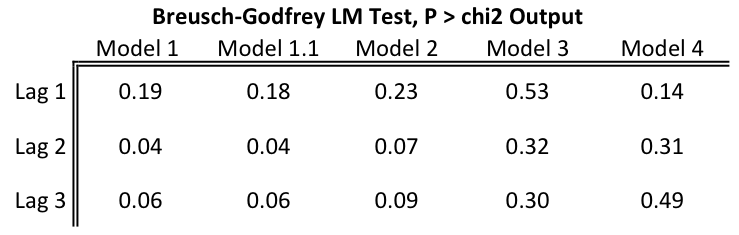

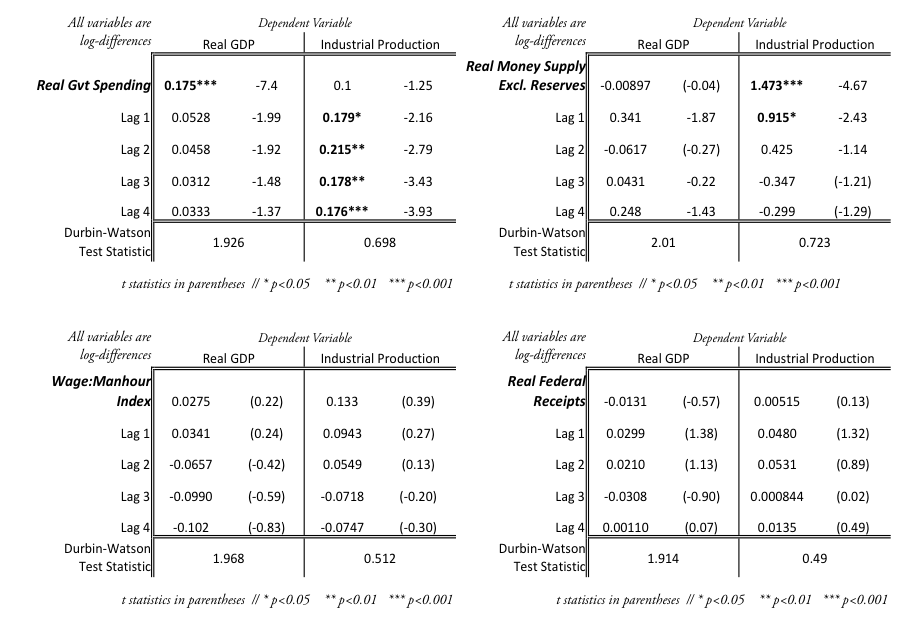

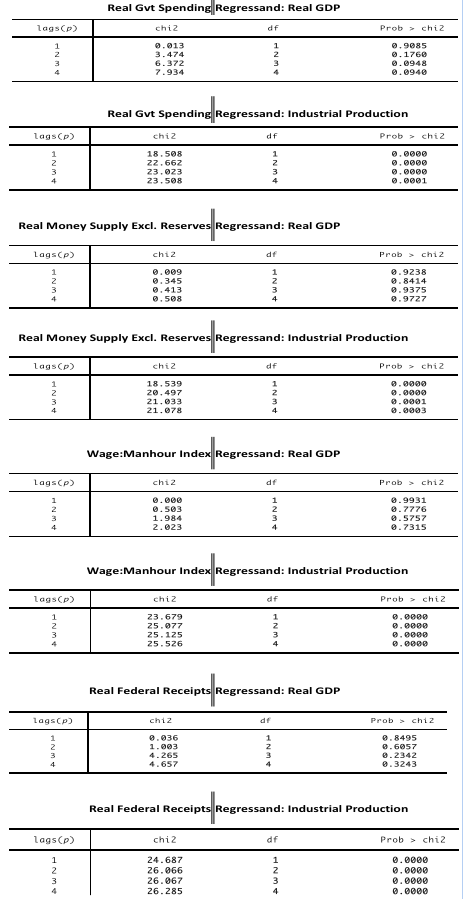

Table A-4. Simple regression of each independent variable on GDP or industrial production.

Table A-5. Breusch-Godfrey Test Results for Table A-4 regressions.

Figures

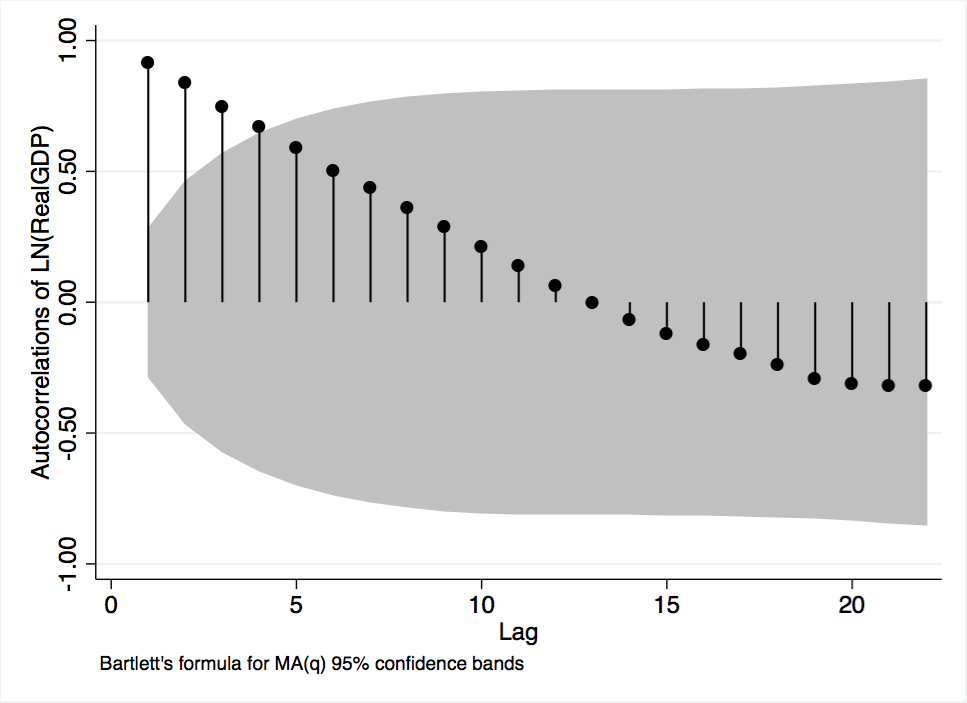

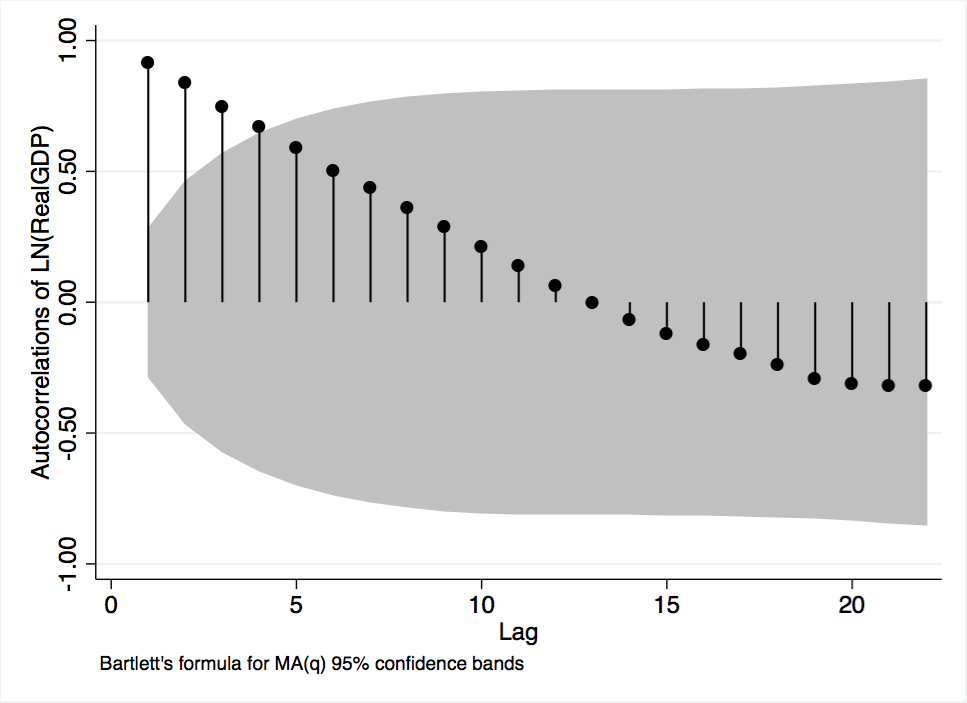

Figure A-1. Autocorrelation plot of GDP variable.

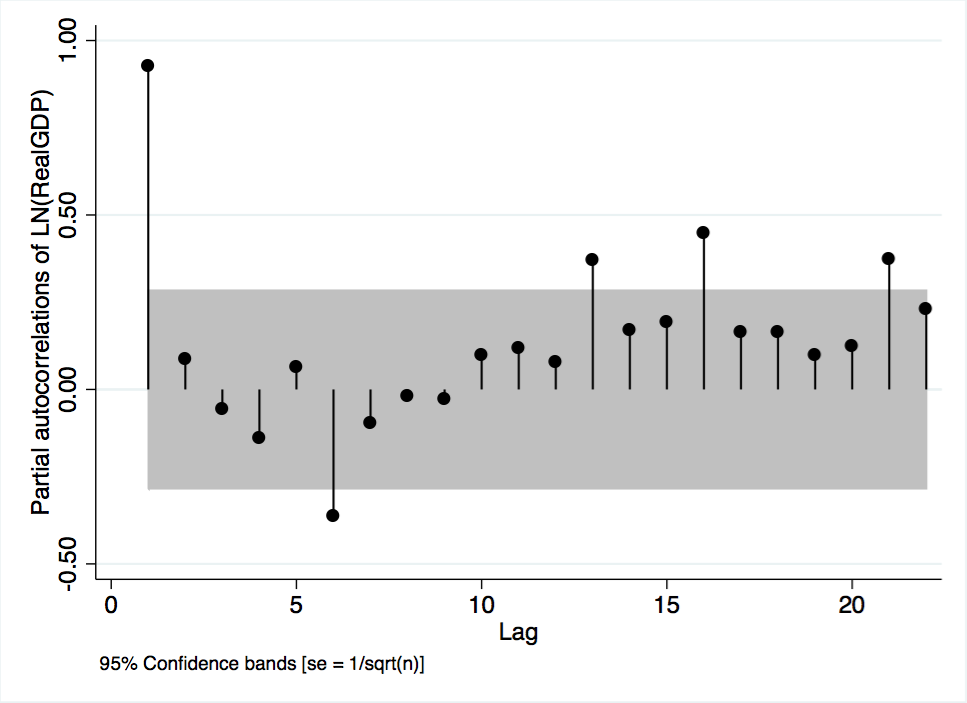

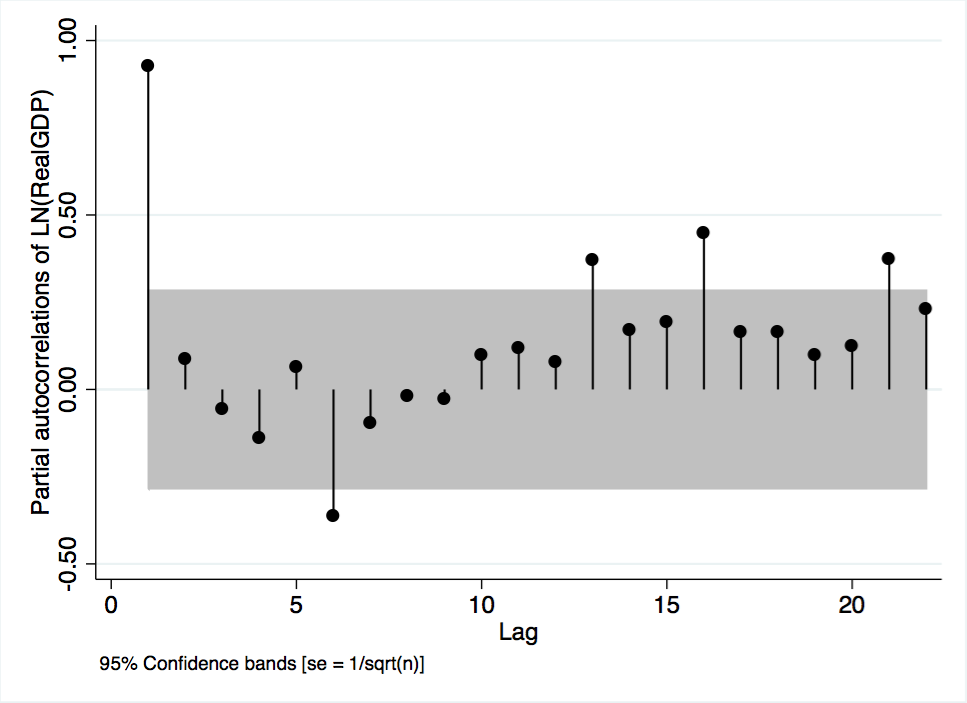

Figure A-2. Partial autocorrelation plot of GDP variable.

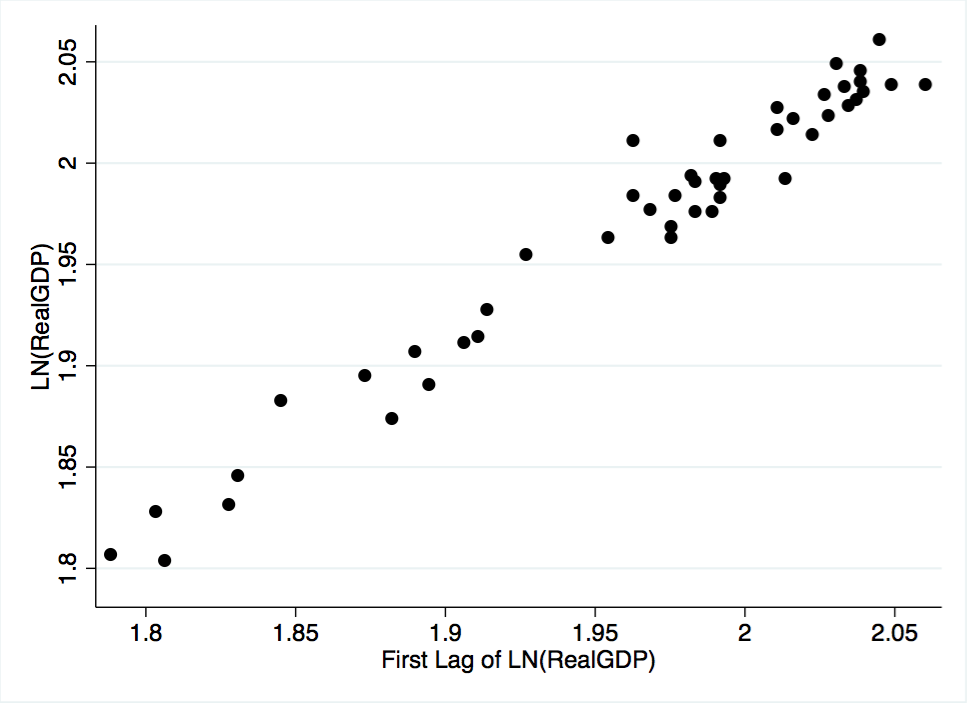

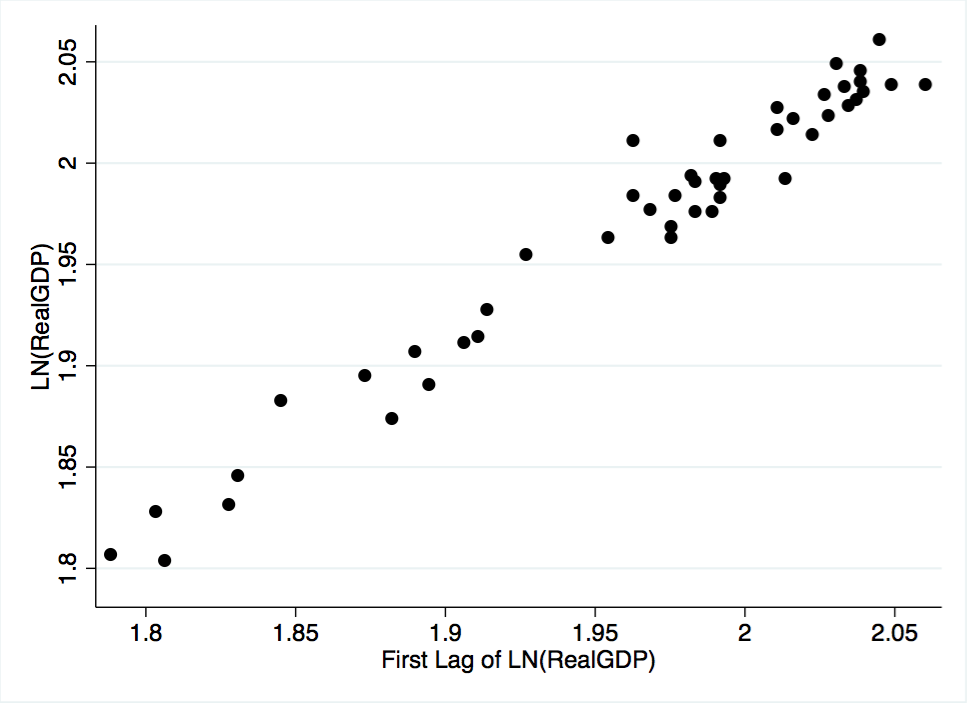

Figure A-3. Scatterplot of the GDP variable against its first lag.

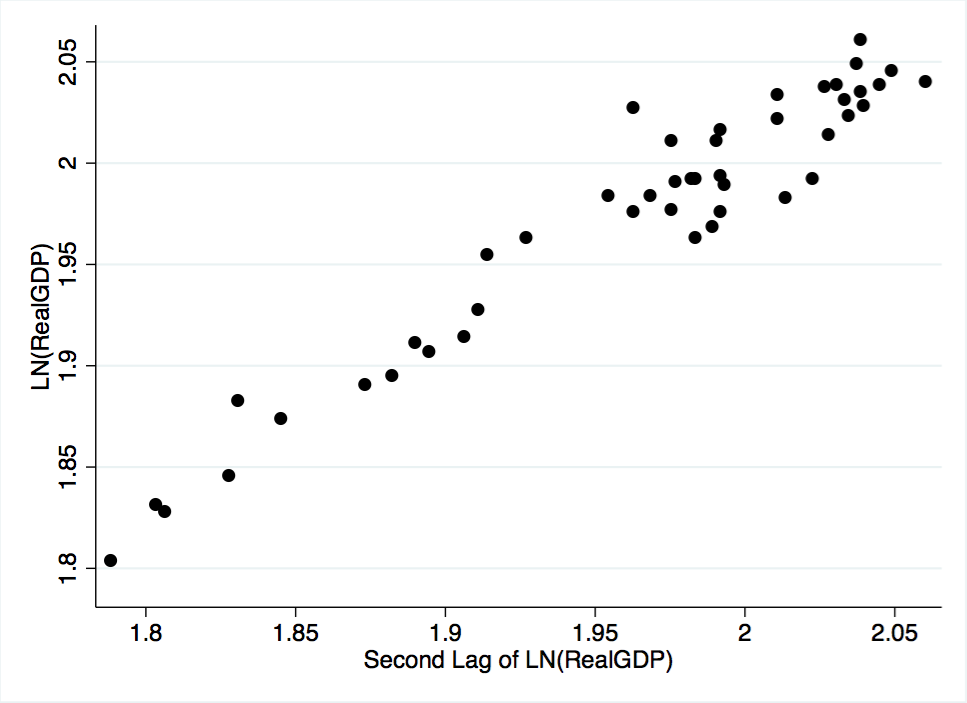

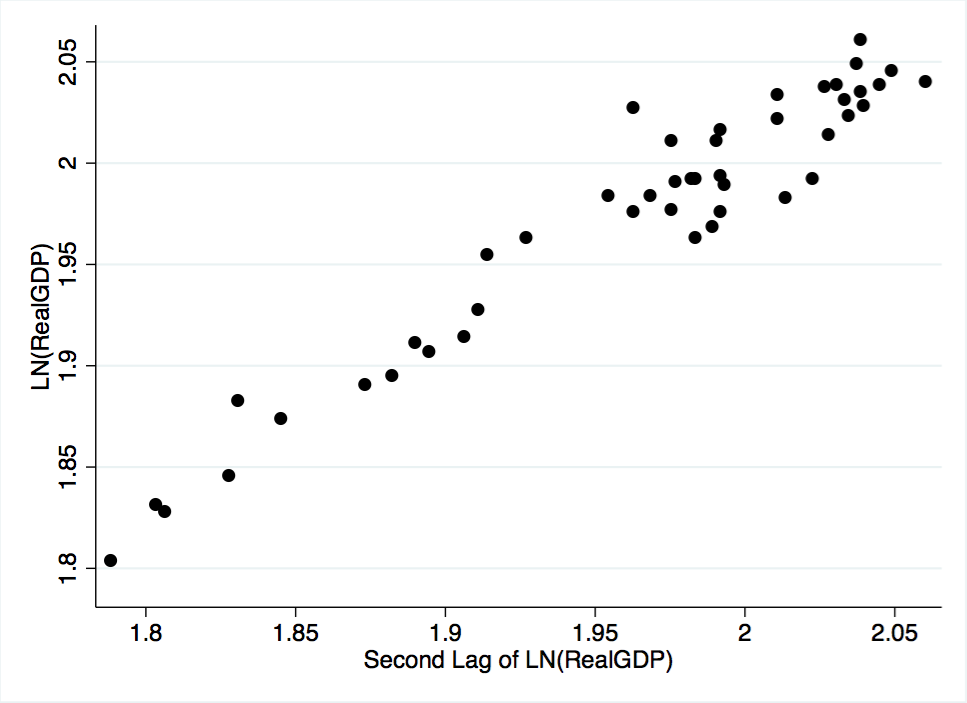

Figure A-4. Scatterplot of the GDP variable against its second lag.

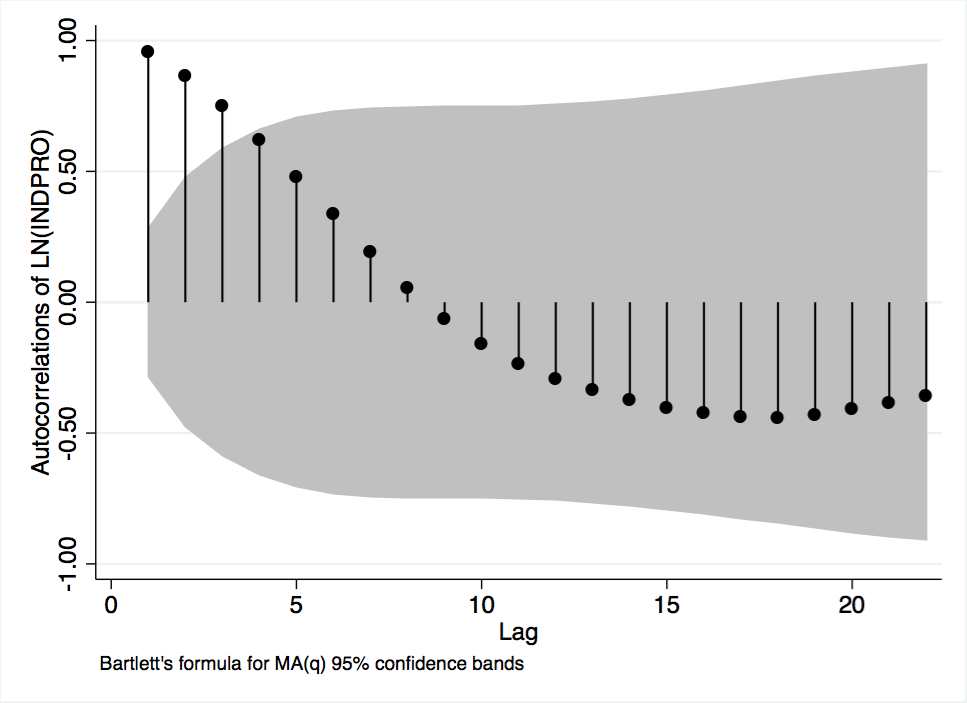

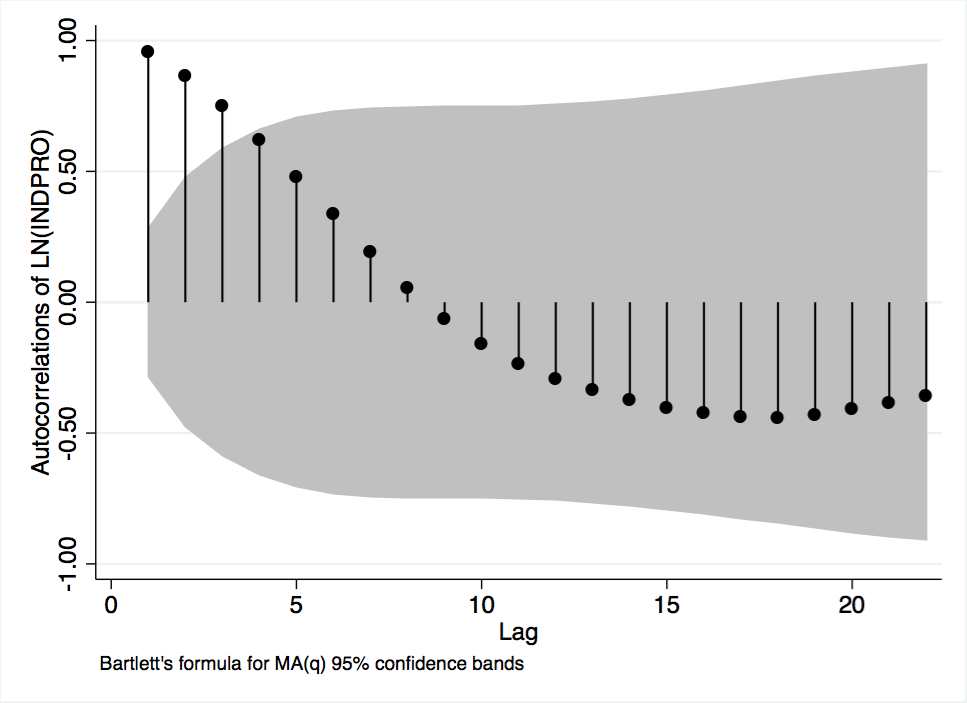

Figure A-5 Autocorrelations of Industrial Production

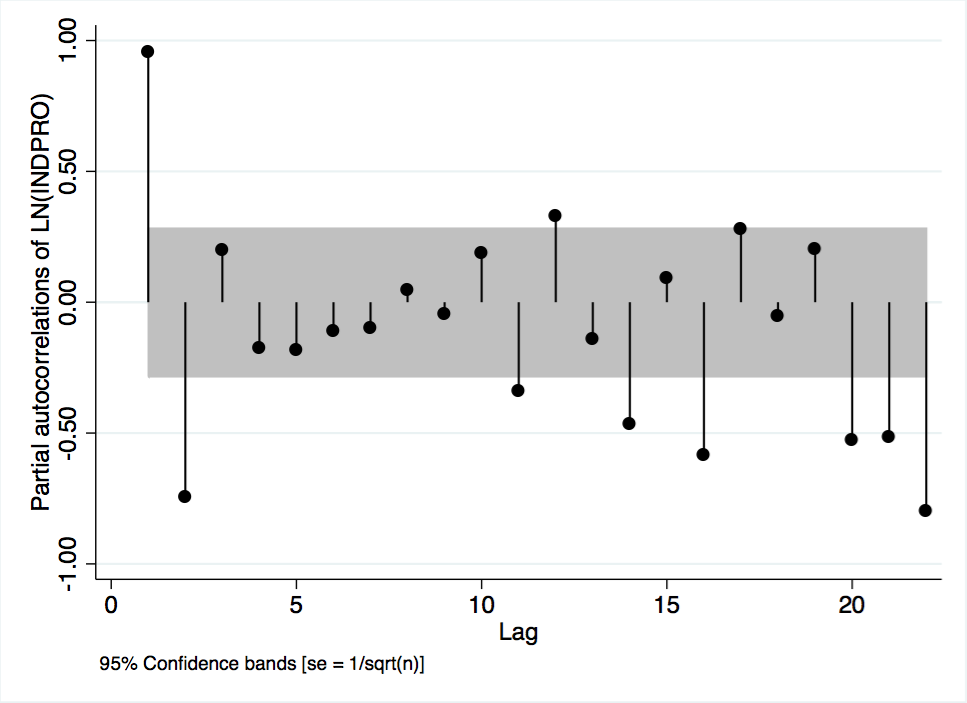

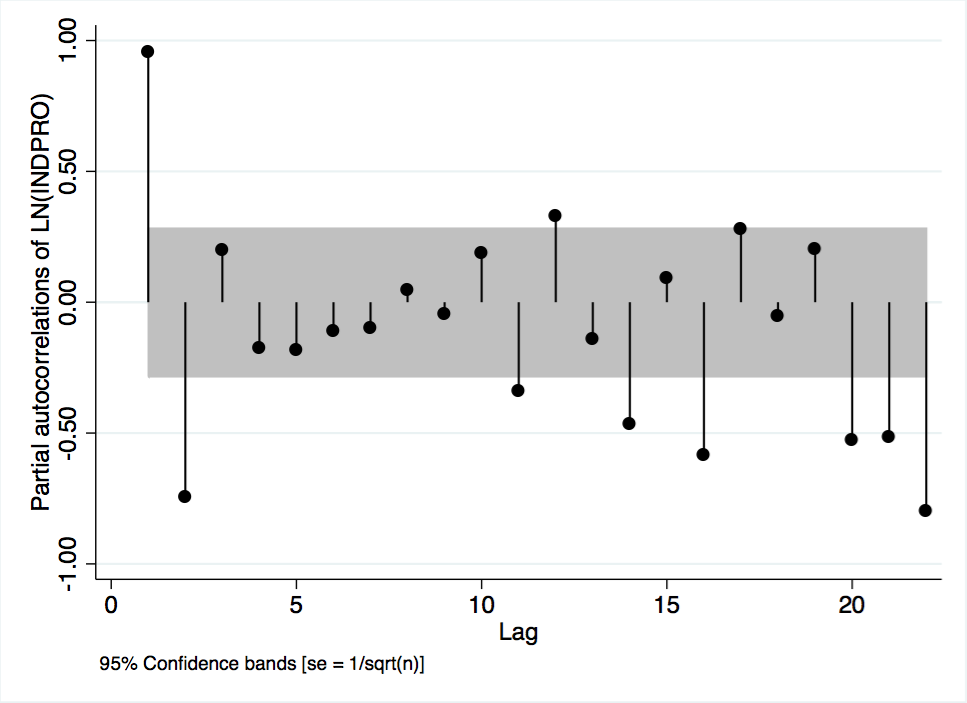

Figure A-6 Partial Autocorrelations of Industrial Production

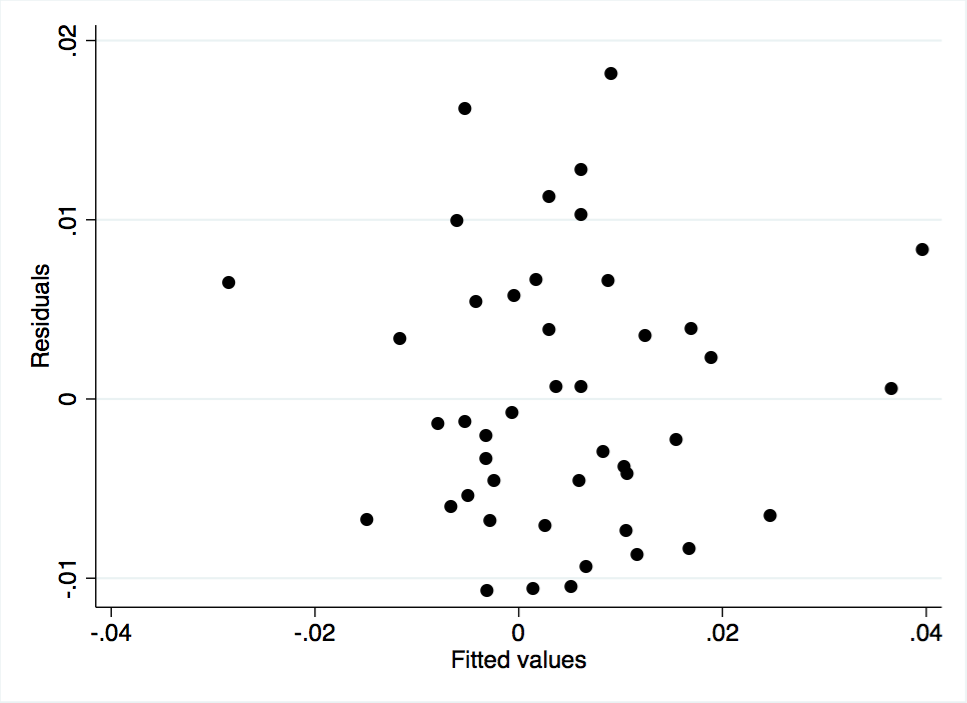

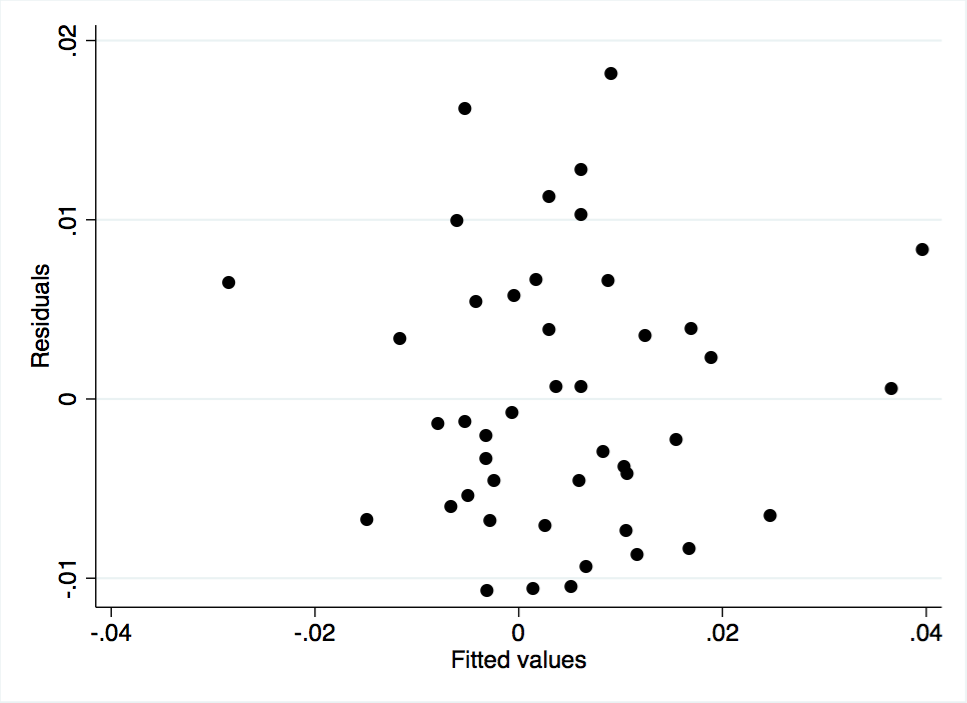

Figure A-7 Scatterplot of Model 1 Residuals Against Fitted Values

Figure A-8 Histogram of Model 1 Residuals

Figure A-9 Model 1 Residuals Plotted Over Time

Figure A-10 Autocorrelations of Model 1 Residuals

Figure A-11 Partial Autocorrelations of Model 1 Residuals

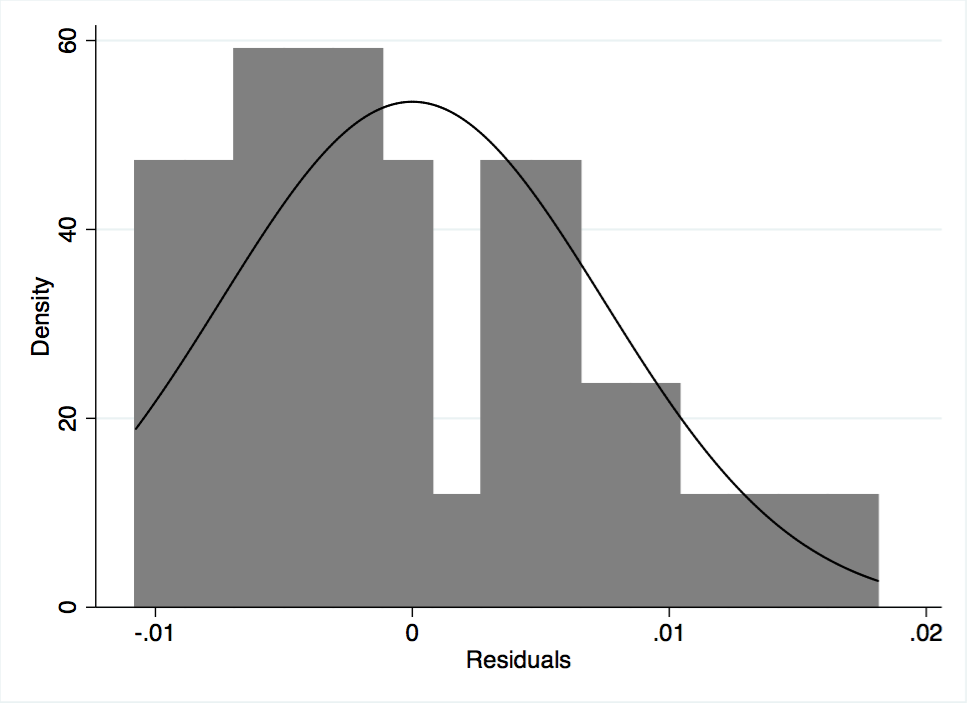

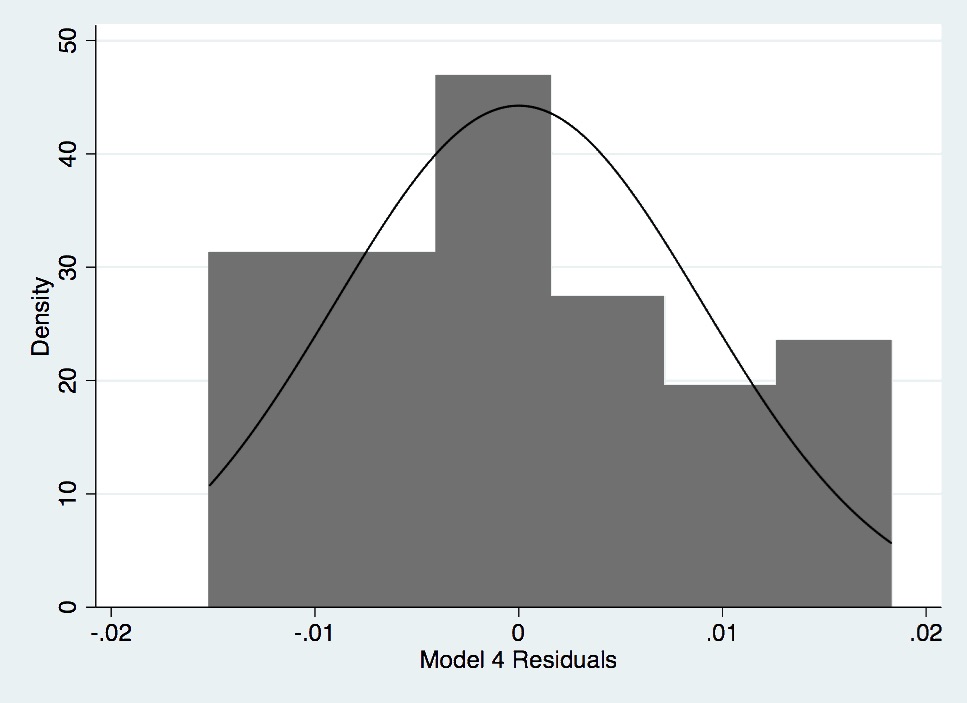

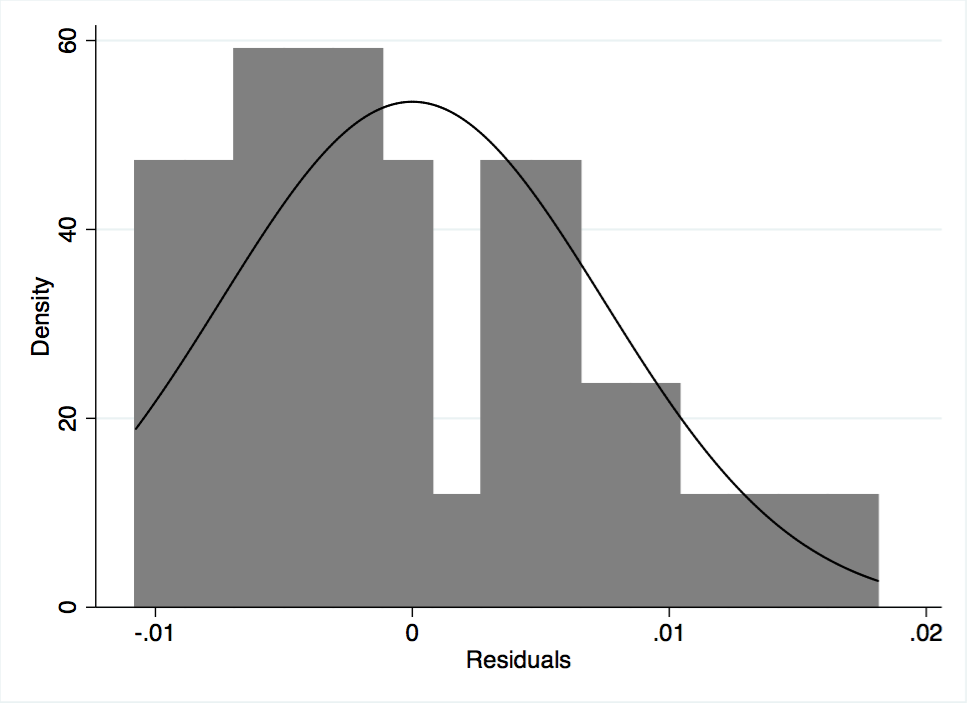

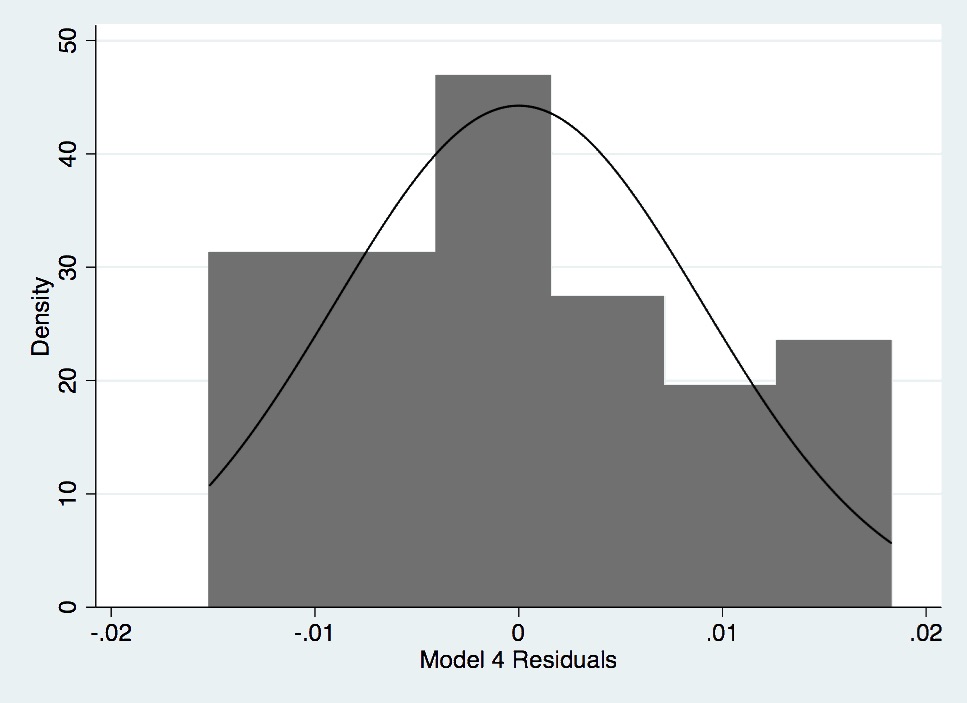

Figure A- 12. Histogram of Model 4 Residuals.

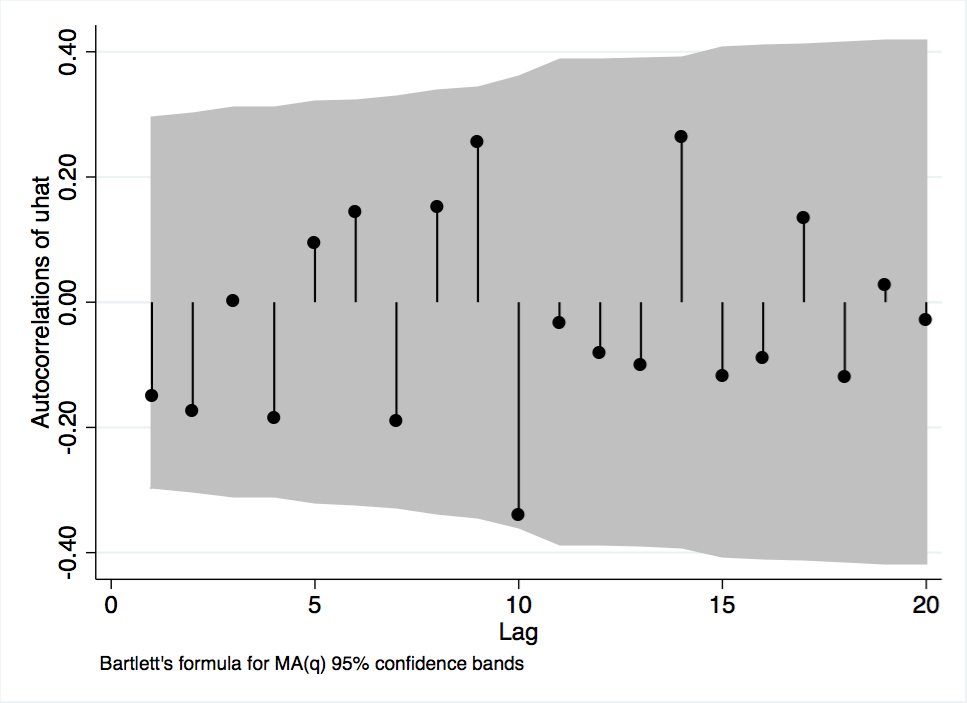

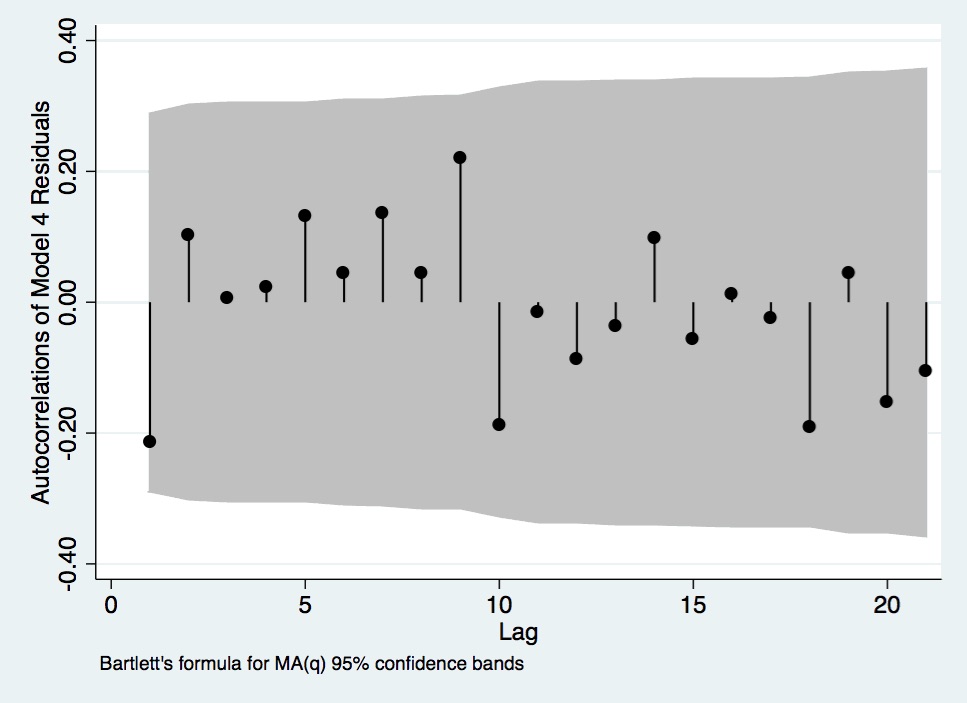

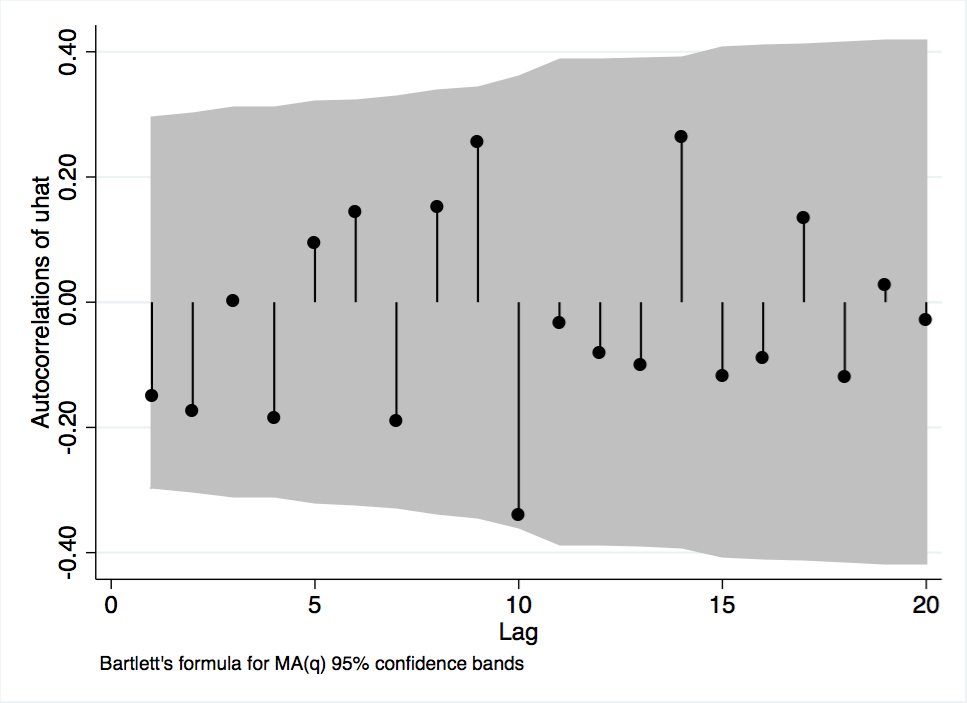

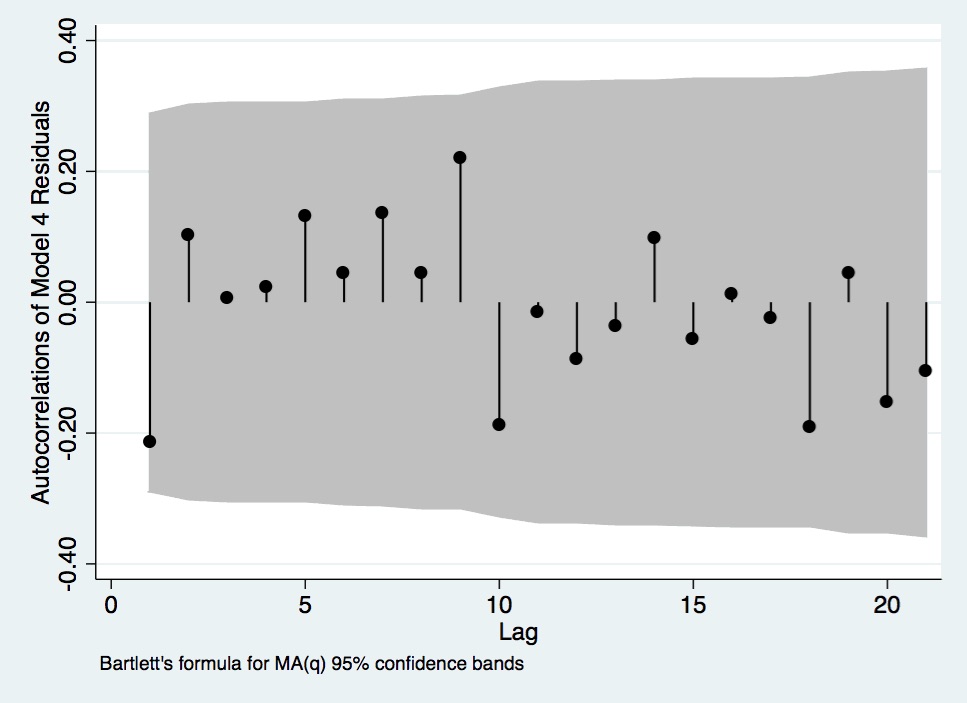

Figure A- 13. Autocorrelations of Model 4 Residuals.

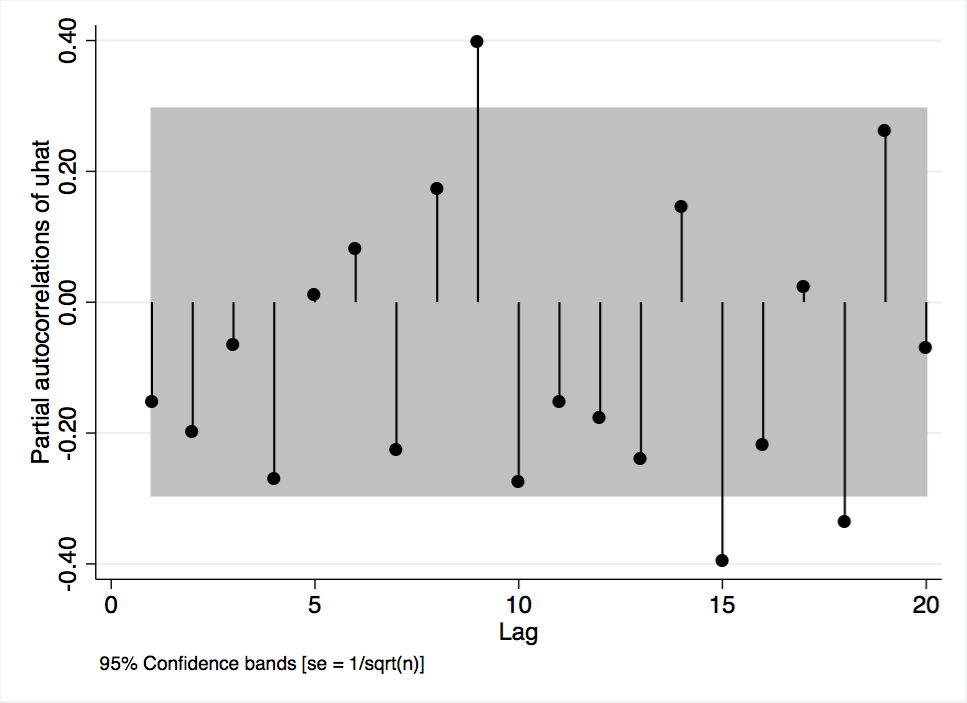

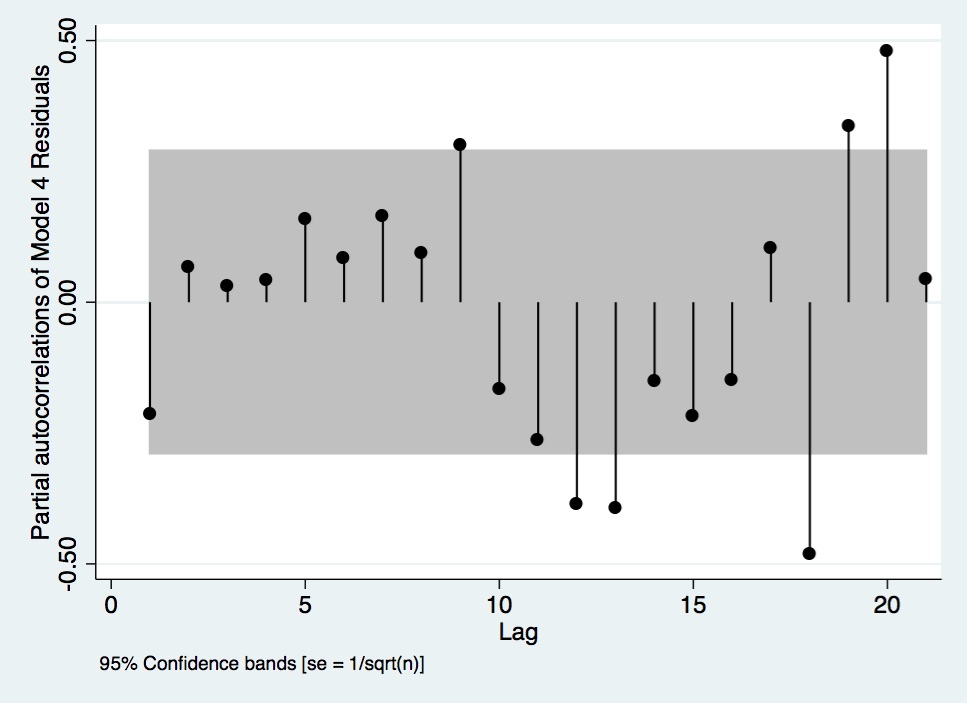

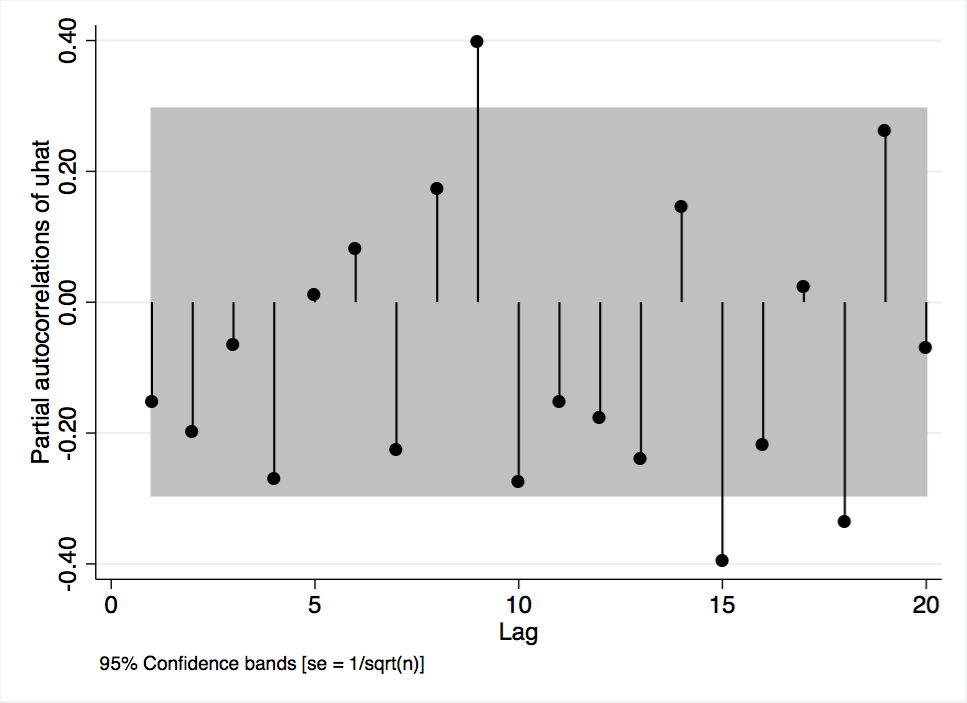

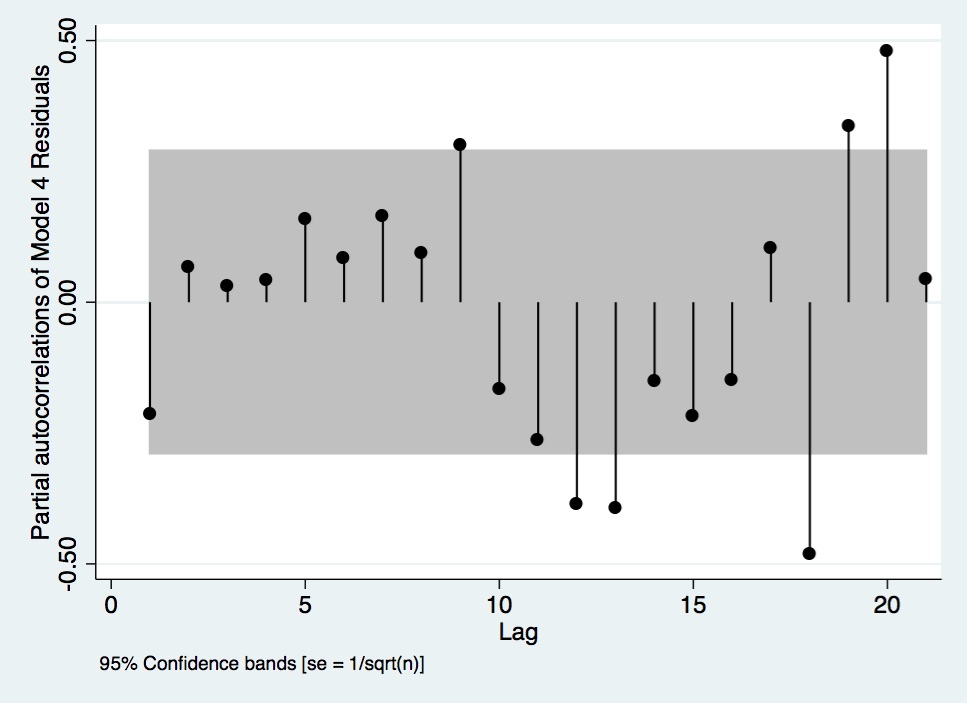

Figure A- 14. Partial Autocorrelations of Model 4 Residuals.

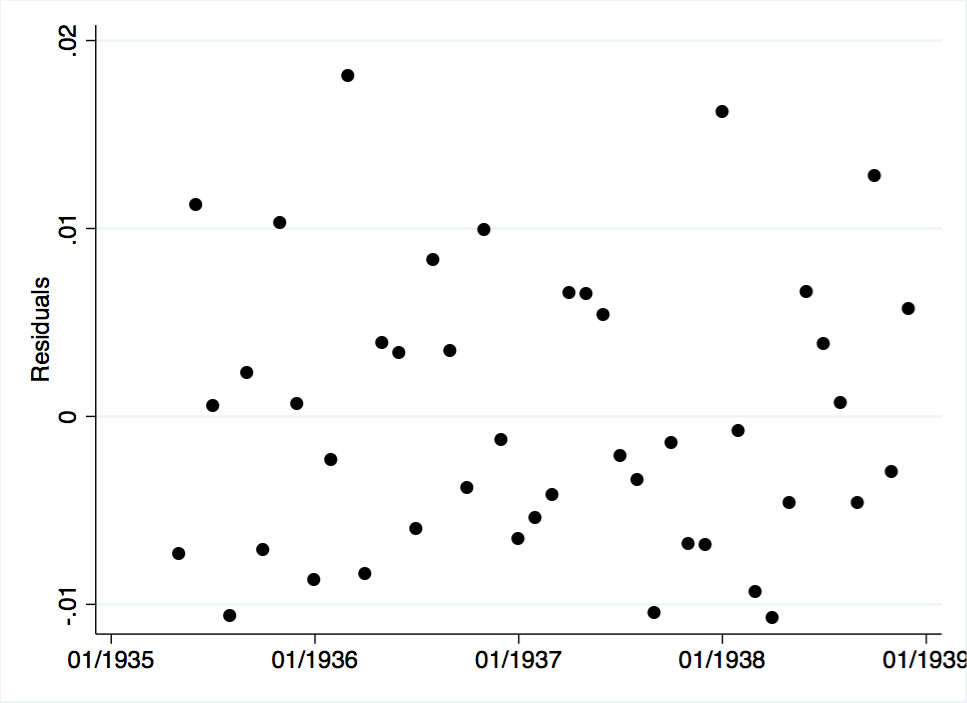

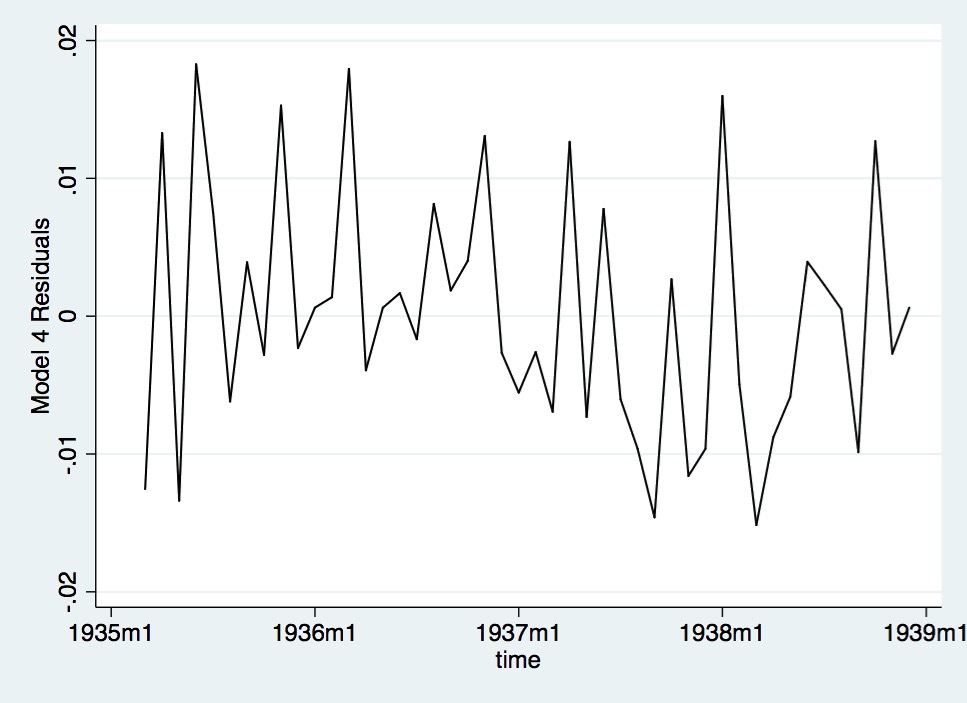

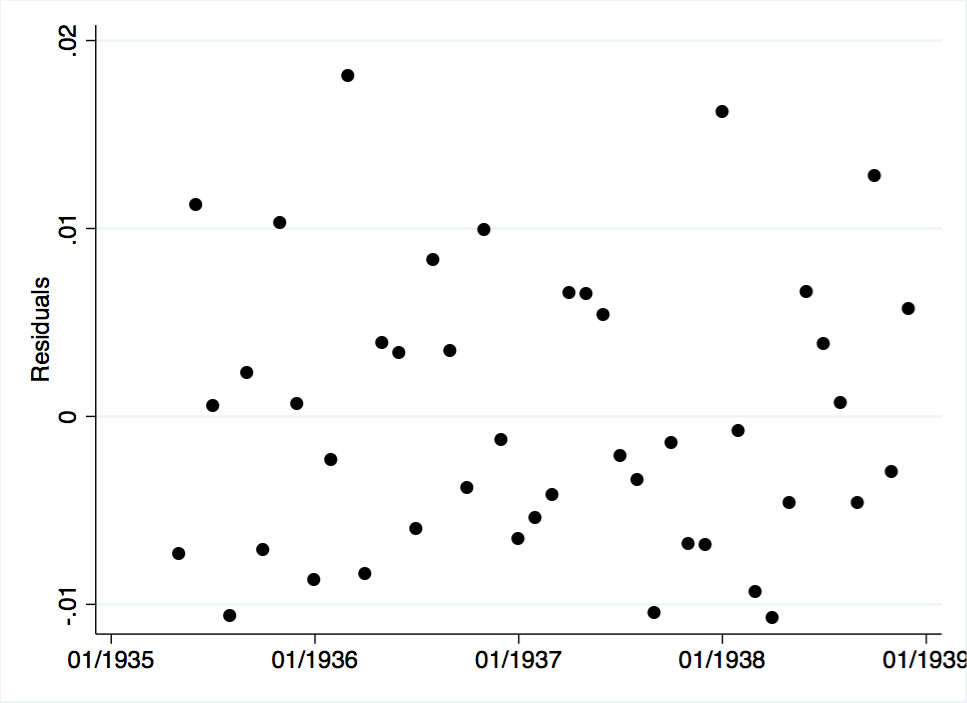

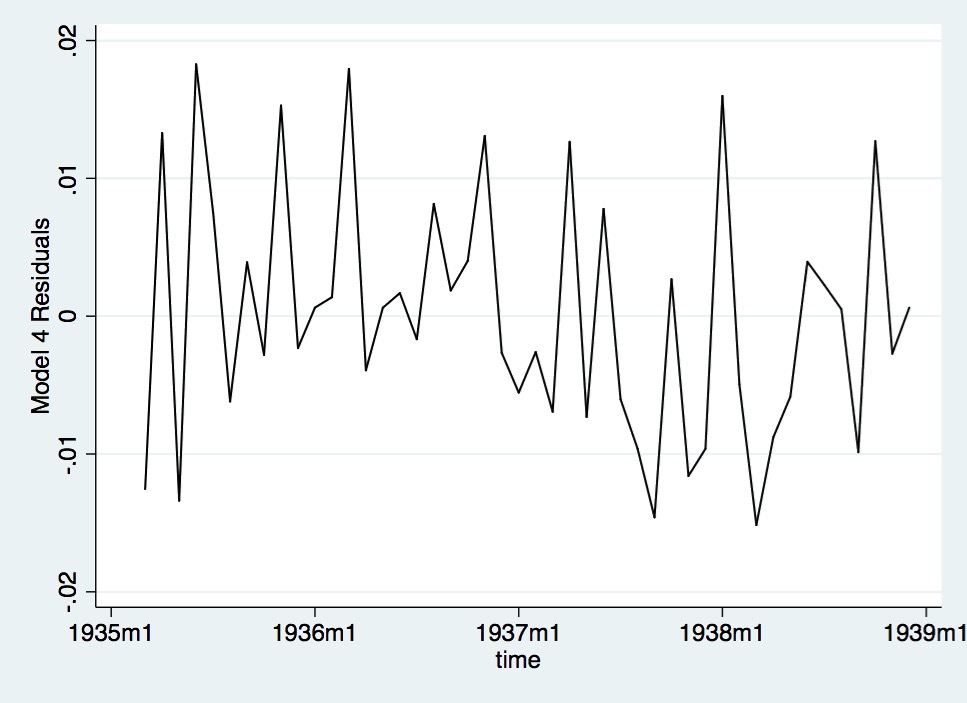

Figure A- 15. Lineplot of Model 4 Residuals.

Save Citation » (Works with EndNote, ProCite, & Reference Manager)

APA 6th

Rafti, J. (2015). "Roosevelt's Recession: A Historical and Econometric Examination of the Roots of the 1937 Recession." Inquiries Journal/Student Pulse, 7(06). Retrieved from http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/a?id=1053

MLA

Rafti, Jonian. "Roosevelt's Recession: A Historical and Econometric Examination of the Roots of the 1937 Recession." Inquiries Journal/Student Pulse 7.06 (2015). <http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/a?id=1053>

Chicago 16th

Rafti, Jonian. 2015. Roosevelt's Recession: A Historical and Econometric Examination of the Roots of the 1937 Recession. Inquiries Journal/Student Pulse 7 (06), http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/a?id=1053

Harvard

RAFTI, J. 2015. Roosevelt's Recession: A Historical and Econometric Examination of the Roots of the 1937 Recession. Inquiries Journal/Student Pulse [Online], 7. Available: http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/a?id=1053

Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

After years of economic downturn and recovery, the debate over stimulus packages and countercyclical policy continues globally. Proponents of such policies claim that the various stimulus packages and policy initiatives around the globe helped bring about quicker recovery, while opponents claim that in many cases these policies... MORE»

The Obama presidency will largely be defined by the administration’s ability to respond to the unique and historic challenge facing the country at the time of his inauguration: the Great Recession. This paper evaluates the president’s success throughout both of his terms in enacting an economic policy, which was largely... MORE»

The “Great Recession” of 2008 resulted in unprecedented levels of state deficit spending.[1] However, even though deficits are partly the result of economic forces beyond the control of state governments&mdash... MORE»

An exhibition entitled “The Quilts of Gee’s Bend” opened at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York in November, 2002 (McGee), bringing worldwide attention to a secluded hamlet in a curve of the Alabama River. Unbeknownst to many of the admirers of these brightly patterned blankets was that the national spotlight had once before been shone on the town. That time... MORE»

Latest in Economics

2020, Vol. 12 No. 09

Recent work with the Economic Complexity Index (ECI) has shown that a country’s productive structure constrains its level of economic growth and income inequality. Building on previous research that identified an increasing gap between Latin... Read Article »

2018, Vol. 10 No. 10

The value proposition in the commercial setting is the functional relationship of quality and price. It is held to be a utility maximizing function of the relationship between buyer and seller. Its proponents assert that translation of the value... Read Article »

2018, Vol. 10 No. 03

Devastated by an economic collapse at the end of the 20th century, Japan’s economy entered a decade long period of stagnation. Now, Japan has found stable leadership, but attempts at new economic growth have fallen through. A combination of... Read Article »

2014, Vol. 6 No. 10

In July 2012, Spain's unemployment rate was above 20%, its stock market was at its lowest point in a decade, and the government was borrowing at a rate of 7.6%. With domestic demand depleted and no sign of recovery in sight, President Mariano Rajoy... Read Article »

2017, Vol. 9 No. 10

During the periods of the Agrarian Revolt and the 1920s, farmers were unhappy with the economic conditions in which they found themselves. Both periods witnessed the ascent of political movements that endeavored to aid farmers in their economic... Read Article »

2017, Vol. 7 No. 2

In 2009, Brazil was in the path to become a superpower. Immune to the economic crises of 2008, the country's economy benefitted from the commodity boom, achieving a growth rate of 7.5 per cent in 2010, when Rousseff was elected. A few years later... Read Article »

2012, Vol. 2 No. 1

The research completed aimed to show that the idea of fair trade, using the example of goals for the chocolate industry of the Ivory Coast, can be described as an example of the economic ideal which Karl Marx imagined. By comparing specific topics... Read Article »

|