Featured Article:The Legacy of International Cooperation at the Nuremberg Trials

By

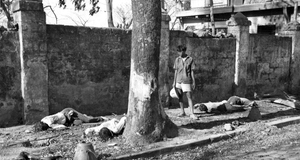

2011, Vol. 3 No. 10 | pg. 2/2 | « The Complicity of the Soviets: A Precursor to the Cold WarThe actual trials for war crimes and crimes against humanity, handled by the French and Soviets were far less contentious and, in many, respects self-explanatory. The Nuremberg trials are, in retrospect, remembered for prosecuting the Nazi leadership for its attempted genocide of the Jews and countless other groups of civilians who did not explify their concept of the German master race. However, the participation of the Soviets in these particular crimes troubled some of the American prosecutors. Thomas J. Dodd, who was second to Jackson and went on to serve as the United States Senator from Connecticut, wrote to his wife: “The Russian participation in this prosecution is the Achilles heel of the great trial. Some day we may have to explain it.”29 His letters to his wife, published long after his death, are filled with suspicious and criticisms of the Soviets, drawing on conflicts from before the war and foreshadowing the coming Cold War. The Soviet Union had been a problematic ally from the beginning—only fighting against in response to being attacked by Germany in 1943. The Soviets had signed a Non-Aggression Pact with Germany in 1939 and had partitioned Poland between them after Germany’s invasion. They had also invaded Finland and several other Baltic states and signed a pact of neutrality with Japan shortly before Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the Soviet Union. The US included the Soviets in the Lend-Lease Act. According to Kochavi, the British were so eager to gain the military power of the Soviets that “if necessary, the British would sacrifice their relations with Poland,”30 whose government-in-exile had been recognized by Great Britain. The Soviets committed great atrocities as a result of their invasion from the East. The worst example of their brutal violence was innumerable report of rape among the civilian female population. The Red Army’s advance through Hungary, Silesia and East Prussia were accompanied by these reports. “The screams of help from the tortured could be heard day and night,” Norman M. Naimark wrote.31 He cited the anti-Nazi propaganda used the Soviet government which inflamed the regular soldiers. The brutal violence continued into the occupation period. During the summer of 1946, while the Nuremberg trial was under way across the country, the following was reported:

Though the Soviet administration and officers tried to crack down on this type of violence, particularly after occupation began, reports continued through the founding of the German Democratic Republic. There was no mention of the countless Soviet rapes of German women or even Nazi-Soviet Pact made at the trial. Instead, the Russian counsel, in his presentation, whitewashed the Soviet participation in the Polish invasion, leading Göring to comment: “I did not think they [the Russians] would be so shameless as to mention Poland.”33 Ehrenfreund defended the participation of the Soviets “in light of the tremendous losses suffered by soldiers and civilians of the USSR at the hands of Nazis…they deserve to be there.” 34 Without question, Stalin was a dictator, and the Russian atrocities committed against Germans—women, specifically—were in many ways comparable to some of the crimes of the Nazis, but the Russians had lost twenty-five million men and in that respect, had earned a right to be represented at the trials. There was a continual breakdown between the powers as the trial progressed though it never seriously threatened the process. It was, rather, the passing of an important military alliance, without which the Allies could not have won the war. Ehrenfreund, who observed the surrender of Germany at the end of the war, observed Nuremberg trials, long after other journalists returned home, bored by the prosecution’s reliance on documents rather than the excitement of witnesses. He remembered celebrating the end of the war with Soviet soldiers, and then not being able to speak with fellow Soviet journalists. “This was certainly a drastic change from that day in May 1945 when we celebrated the meeting of our armies on the banks of the Enns River in Austria.” 35 The tensions between the Soviet Union and the Western democracies became more apparent after former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill delivered a speech on March 5, 1946 in Fulton, Missouri, using the iron curtain description for the first time in reference to the Soviet Union. Dodd wrote to this wife: “I would not be surprised if this trial broke up—or at least if the Russians withdrew. Of course they will probably back down—they always do when their bluff is called…they are no different from the Nazis—the same breed of cat and they are predatory and aggressive and they intend to run the world.”36 The Legacy of International CooperationThe cooperation seen at Nuremberg and during the International Military Tribunal Charter negotiations seems implausible now, with what is now known about the ensuing Cold War, the revelations of Soviet complicity in the early years of the war, and the breakdown of international relations beginning with the Berlin blockade in 1948. The process might have been complicated at every turn with unfamiliarity with legal systems, the ambiguities of international law and the victorious powers’ hands not being as clean as one would hope. However, the Nuremberg trial was not a show trial, with the guilt of the German defendants already decided. The Soviet delegate, Major General Ion T. Nikitchenko, found this position very difficult, according to Ehrenfreund. “The fact that the Nazi leaders are criminals has already been established. The task of the Tribunal is only to determine the measure of guilt.”37 Jackson fought against this vigorously at the London conference, and was able to sway the rest of the delegation to his view. The trial at Nuremberg was not simply, as many called it, the winners punishing the losers, though that was certainly a factor. Heinz Eulau, a political science theorist wrote at the time:

However, the importance of Nuremberg and the international cooperation achieved there was more than just punishing the Nazis for those deaths. Nuremberg provided a voice for those that had been silenced by the war and the Nazi regime and its record is its most enduring legacy. Of the legacy created in all the proceedings at Nuremberg, Ehrenfreund wrote, “But like the main trial, perhaps the most valuable contribution of the twelve other trials was to provide a permanent and authoritative record of the Holocaust and of the barbarism to which civilized human beings can descend.”39 On this Otto Kranzbühler could agree. “For the historical knowledge, the Nuremberg material is a valuable resource, but it must be drawn from with caution.”40 The International Military Tribunal that oversaw the trials in Nuremberg would eventually give way to the United Nations, and other international committees, specifically NATO and the more recent International Criminal Court. Unlike the aftermath of World War I, in which the countries involved retreated into their own isolation only to face a more devastating war two decades later, the post-World War II period has fostered an international community that is rooted in the perception that no person, no group, no government can make a decision that would adversely impact other nations without penalty. A contributor to The New Republic wrote, “They [the Nuremberg judges] hoped to set forward the standards of civilization, so that any nation contemplating war in the future would be deterred by the prospect that the statesmen who plot such a war are liable to be taken out and hanged.”41 It is true that the trials at Nuremberg have not ended wars or military actions. Genocide, unfortunately, continues around the world. In Europe, however, it is safe to conclude that Nuremberg served its purpose—a continental war on the scale of the twentieth century seems unthinkable, especially with the emergence of the European Union. Herman Phlefger, who worked on behalf of the Allied military government in Germany after 1945, wrote of the trial, “I take it as a remarkable display of international cooperation that agreement should have been reached on a matter so close to the national prejudices of all, and that resultant procedure, both in theory and fact, should conform so closely to our own idea of justice.”42 The trials at Nuremberg and the unprecedented international cooperation despite ideological and procedural issues can offer some hope for future areas of cooperation between nations that are so different, as the United States and the Soviet Union were in the 1940s. ReferencesSecondary SourcesEhrenfreund, Norbert. The Nuremberg Legacy: How the Nazi War Crimes Trials Changed the Course of History. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007. Kochavi, Arieh. Prelude to Nuremberg: Allied War Crimes Policy and the Question of Punishment. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998. Landsman, Stephan. Crimes of the Holocaust: The Law Confronts Hard Cases. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005. Naimark, Norman M., The Russians in Germany: A History of the Soviet Zone of Occupation, 1945-1949. Cambridge: The Belknap Harvard University Press, 1995. Persico, Joseph E. Nuremberg: Infamy on Trial. New York: Viking Penguin, 1994. MemoirsDodd, Christopher. Letters from Nuremberg: My Father’s Narrative of a Quest for Justice. New York: Crown Publishing, 2007. Harris, Whitney R. Tyranny on Trial: The Trial of the Major German War Crimines at the End of World War II at Nuremberg, Germany, 1945-46. Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press, 1999. Kranzbühler, Otto. Rückblick auf Nürnberg. Hamburg: Zeit-Verlag E. Schmidt & Co.. 1949. Mettraux, Guénaël, ed. Perspectives on the Nuremberg Trial. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008. Sprecher, Drexel A. Inside the Nuremberg Trial: A Prosecutor's Comprehensive Account. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1999. Taylor, Telford. The Anatomy of the Nuremberg Trials: A Personal Memoir. New York: Alfred A. Knof, 1992. Primary SourcesTrial of The Major War Criminals before The International Military Tribunal. Vol. 1. Buffalo: William S. Hein & Co., Inc., 1995. Originally published 1947 by US Government “The Results at Nuremberg”, New Republic 115, no. 15 (October 14, 1946) 467-468. Eulau, Heinz, “The Nuremberg War-Crimes Trial: Revolution in International Law”, New Republic 20, no. 113 (1945: November 12): 625-628. Phleger, Herman, “Nuremberg – A fair trial?: Dynamic law”, The Atlantic 177 (1946: Jan/June): 60-65. Stimson, Henry L., “The Nuremberg Trial: Landmark in Law”, Foreign Affairs 25, no. 2 (1945/47) 179-89. Wyzanski, Jr., Charles E., “Nuremberg-A fair trial?: Dangerous precedent”, The Atlantic 177 (1946: Jan/June): 66-70. Wyzanski, Jr., Charles E., “Nuremberg in Retrospect”, The Atlantic 178 (1946: July/Dec): 56-59. Endnotes1.) Trial of The Major War Criminals before The International Military Tribunal, Vol. 2 (Buffalo: William S. Hein & Co., 1995), 100. 2.) Stephan Landsman, Crimes of the Holocaust: The Law Confronts Hard Cases, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005), 15. 3.) Robert H. Jackson., “The Challenge of International Lawlessness”, in Perspectives on the Nuremberg Trial, ed. Mettraux, Guénaël, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 11. 4.) Thomas J. Dodd, “The Nurnberg Trials” in Perspectives on the Nuremberg Trial, ed. Mettraux, Guénaël, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 191. 5.) Stefan Glaser, “The Charter of Nuremberg Tribunal and New Principles” in Perspectives on the Nuremberg Trial, ed. Mettraux, Guénaël, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 55. 6.) Stimson, Henry L., “The Nuremberg Trial: Landmark in Law”, Foreign Affairs 25, no. 2 (1945/47) , 179. 7.) Ehrenfreund, 216. 8.) Sheldon Glueck, “The Nuernberg Trial and Aggressive War”, in Perspectives on the Nuremberg Trial, ed. Mettraux, Guénaël, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 82. 9.) Drexel A. Sprecher., Inside the Nuremberg Trial: A Prosecutor's Comprehensive Account, ( Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1999),, 17. 10.) Stimson, 179. 11.) Sprecher, 27. 12.) Ibid, 31. 13.) Kochavi, Arieh, Prelude to Nuremberg: Allied War Crimes Policy and the Question of Punishment, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998), 83. 14.) Ehrenfreund,10. 15.) Ehrenfreund, 7. 16.) Kochavi, 72. 17.) Stimson, 180. 18.) Ehrenfruend, 219. 19.) Sprecher, 97 20.) Taylor Telford, The Anatomy of the Nuremberg Trials: A Personal Memoir, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1992), 153. 21.) Taylor, 155. 22.) Ehrenfreund, 99. 23.) Ehrenfreund, 14-15. 24.) Henry L. Stimson, “The Nuremberg Trial: Landmark in Law”, in Perspectives on the Nuremberg Trial, edit. Mettraux, Guénaël, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 619 25.) Ibid, 620. 26.) Der Unterschied dieser Maßstäbe gegenüber denen, he wrote, die auf deutsche Soldaten in Nürnberg angewandt wurden, ist offensichtlich.“ Otto Kranzbühler, Rückblick auf Nürnberg, (Hamburg: Zeit-Verlag E. Schmidt & Co.), 1949), 14. 27.) Otto Kranzbuhler, “Nuremberg Eighteen Years Afterwards”, ed. Mettraux, Guénaël, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 444. 28.) Wyzanski, Jr., Charles E., “Nuremberg in Retrospect”, The Atlantic 178 (1946: July/Dec), 57. 29.) Dodd, Christopher, Letters from Nuremberg: My Father’s Narrative of a Quest for Justice, (New York: Crown Publishing, 2007), 341. 30.) Kochavi, 10. 31.) Norbert M. Naimark, The Russians in Germany: A History of the Soviet Zone of Occupation, 1945-1949, (Cambridge: The Belknap Harvard University Press, 1995), 74. 32.) Ibid, 87. 33.) Taylor, 307. 34.) Ehrenfreund, 62. 35.) Ehrenfreund, 105. 36.) Dodd, 251. 37.) Ehrenfreund, 13. 38.) Eulau, Heinz, “The Nuremberg War-Crimes Trial: Revolution in International Law”, New Republic 20, no. 113 (1945: November 12), 628. 39.) Ibid, 104. 40.) Für die geschichtliche Erkenntnis nietet daher das Nürnberger Material eine wertvolle Quelle, aber eine Quelle, aus der mit großer Vorsicht geschöpft werden muß. Kranzbuhler, 41.) “The Results at Nuremberg”, New Republic 115, no. 15 (October 14, 1946), 468. 42.) Phleger, Herman, “Nuremberg – A fair trial?: Dynamic law”, The Atlantic 177 (1946: Jan/June), 62. Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in History |