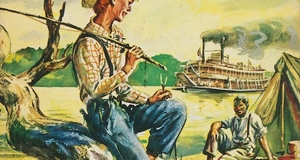

The Father-Son Relationship of Jim and Huck in Mark Twain's Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

By

2014, Vol. 6 No. 11 | pg. 2/2 | « Jim’s own conduct throughout the book demonstrates increasing paternal tendencies toward Huck and a true love and concern for Huck’s well being, although Jim, too, must progressively grow in his trust and understanding of Huck. Forrest Robinson observes that Jim “is from the very outset uneasy with Huck, alert to his acquiescence in the ideology of the slave system, and aware that the boy's best intentions are only half of a perilously divided sensibility.” Jim knows the innate perceptions of a southern-born white boy toward the subordinate black slave and he is initially cautious around Huck, for good reason, and “careful to confirm the boy's prejudiced expectations before moving carefully, imperceptibly beyond them” (Robinson 374). It doesn’t take long for Jim to place his confidence in Huck, however, and long before Huck mentally chooses to support Jim and accept him as permanent family, Jim has already demonstrated love and care as a surrogate father toward Huck. In the hairball scene, in which Jim tells Huck’s “fortune” regarding Pap, Jim begins to display his fatherly instincts toward Huck. Although a simple “magic hairball” that supposedly can speak to Jim is not an impressive object of authority in a father-son relationship, Jim still utilizes it in an authoritative manner and, as Valkeakari points out, “in consoling and advising Huck he actually substitutes for the young boy’s father” (35). Not only does Jim use this action as a sign of authority, but Jim also responds in “genuine human kindness and unselfish generosity” (Valkeakari 34) with the emotional support that Huck desperately needs. As Jim and Huck realize the personal worth of each other and their need for one another, their actions and behavior begin to exhibit the necessary qualities of father and son. Besides the growing paternal inclinations Jim shows toward Huck in the hairball episode and after finding Pap’s body in the houseboat, there are other demonstrations throughout Huck Finn of Jim’s care and concern as a father for his adopted son and his taking responsibility for Huck’s safety and welfare.Several times Huck makes reference to Jim’s selflessness in frequently taking over Huck’s night shifts on the raft during their adventure down the Mississippi River so that Huck “could go on sleeping” (Twain 206). The raft on which Huck and Jim live and travel during the river escapade functions as home for them, a place of “relief from the outside” and a “sanctified place of trust separate from the disguise and duplicity assumed by nearly everyone in the public realm” (Knoper 127). Together, Huck and Jim agree after their departure from the bloody Grangerford-Shepherdson feud that “there warn’t no home like a raft, after all” (Twain 113). In addition, Jim shows a genuine care and sacrificial compliance in subjecting himself to Huck and Tom Sawyer’s multitude of unnecessary and demeaning prison requirements during the evasion episode at the Phelpses’. Jim’s willingness to meekly allow the two younger boys to put him under such humiliating conditions indicates his unconditional love toward and implicit trust in Huck as the “bes’ fren’ Jim’s ever had” and the “on’y white genlman dat ever kep’ his promise to ole Jim” (Twain 87). Ultimately, as Robert Shulman indicates, Huck and Jim’s relationship is characterized by “genuine feelings of joy and grief, real laughter and tears, the authentic language of the heart,” which “all contribute to the value of the family [they] create” (33). Ultimately, Huck and Jim’s relationship is characterized by “genuine feelings of joy and grief, real laughter and tears, the authentic language of the heart,” which “all contribute to the value of the family [they] create." Huck and Jim’s relationship takes on the attributes of a father-son bond for several reasons. The major cause of this unlikely connection is the fact that both have been compelled by chance into a situation that will either require their mutual cooperation or invoke their mutual doom. Both Huck and Jim have been forced to flee from their respective enslaving conditions and, being thrust into each other’s company, they must each, out of necessity, take refuge in the other or else face the prospect of being recaptured. “Long before they learn to respect or love one another,” Robinson points out, “Huck and Jim need each other” (368) in order to survive their voluntary exclusion from public society and obtain their freedom. Additionally, Huck and Jim find a connection and consolation in each other not only because they must survive but also due to a mutual loss of family and a need for substitute family members. Both have lost or given up family members in order to gain the freedom and the better life they desire, leaving a gap in their lives that is waiting to be filled by each other. Jim loves his real family and longs to be reunited with them, but since that is presently an impossibility, he takes up Huck as his child in place of his blood relations and acts as Huck’s father and guardian. Likewise, Huck, because of his broken ties with Pap, accepts Jim as his substitute father. Though he does not immediately appreciate Jim as an equal human being, Huck still has a need for Jim as his father, whether he realizes it or not, and this need acts as a starting point for the development of a strong and unique relationship with Jim. Together, the two create what Shulman calls “sustaining ties” (44) and they “embody a cohesive family” (46) unified by a nearly ideal father-son relationship. Huck Finn contains a timeless portrait of two individuals overcoming the obstacles of two markedly different backgrounds, personalities, and values and finding in each other a true, meaningful relationship that brings them both the strength and determination they need to reach their goals of freedom and equality. With the support they receive from one another, they find their true purposes and arrive at promising points in their lives that would not have been otherwise attainable. Through the many depictions of Huck and Jim and their relations with one another, it is clear that, in contrast to the claims of Leslie Fiedler and Axel Nissen, the two share a unique relationship characterized by the affection and care of a father and child toward one another. Their story is a rarity in the realm of classic literature, communicating a much-needed message to the world that no social or ethnic barrier is too great to surmount for the sake of humanity and equity. ReferencesFiedler, Leslie A. “Come Back to the Raft Ag’in, Huck Honey!” The Devil Gets His Due: The Uncollected Essays of Leslie Fiedler. Ed. Samuele F. S. Pardini. Berkeley: Counterpoint, 2008. 46-53. ebrary. Web. 15 Oct. 2013. Freedman, Carol. “The Morality of Huck Finn.” Philosophy and Literature 21.1 (1997): 102-13. Project MUSE. Web. 15 Oct. 2013. Hansen, Chadwick. “The Character of Jim and the Ending of Huckleberry Finn.” The Massachusetts Review 5.1 (1963): 45-66. JSTOR. Web. 15 Oct. 2013. Joshi, Vijaya Narendra. “Relationship Between Huck and Jim in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.” Indian Streams Research Journal 2.1 (2012): 1-4. Google Scholar. Web. 15 Oct. 2013. Knoper, Randall. “ ‘Away From Home and Amongst Strangers’: Domestic Sphere, Public Arena, and Huckleberry Finn.” Prospects: An Annual of American Cultural Studies 14 (1989): 125-140. bepress. Web. 2 Aug. 2013. Nissen, Axel. “A Tramp at Home: Huckleberry Finn, Romantic Friendship, and the Homeless Man.” Nineteenth-Century Literature 60.1 (2005): 57-86. ProQuest. Web. 25 July 2013. Robinson, Forrest G. “The Characterization of Jim in Huckleberry Finn.” Nineteenth-Century Literature 43.3 (1988): 361-91. JSTOR. Web. 26 July 2013. Shulman, Robert. “Fathers, Brothers, and ‘The Diseased’: The Family and Alienation in Huckleberry Finn.” Social Criticism & Nineteenth-Century American Fictions. Columbia: U of Missouri P, 1987. 28-49. Google Books. Web. 2 Aug. 2013. Solomon, Andrew. “Jim and Huck: Magnificent Misfits.” Mark Twain Journal 16.3 (1972): 17- 24. ProQuest. Web. 25 July 2013. Twain, Mark. The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. New York: Bantam, 1981. Print. Valkeakari, Tuire. “Huck, Twain, and the Freedman's Shackles: Struggling with Huckleberry Finn Today.” Atlantis 28.2 (2006): 29–43. Academic Search Premier. Web. 16 Oct. 2013. Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in Literature |