Featured Article:Scientific Federal Agencies & the United States Negotiation for the Limited Test Ban Treaty, 1962-1963

By

2017, Vol. 9 No. 03 | pg. 1/1

IN THIS ARTICLE

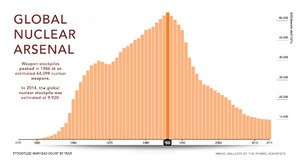

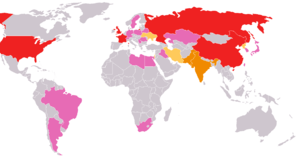

In October of 1962, the United States and Soviet Union’s arms race in ballistic missiles escalated to an unnerving confrontation that lasted thirteen days, while both world leaders waited on opposite sides of the world for the other to say the word and start a nuclear war. This confrontation became known as the Cuban Missile Crisis and is equated to be the climax of the Cold War.1 During these frightening thirteen days, President John F. Kennedy and Premier Nikita Khrushchev deliberated over launching nuclear warheads to begin a nuclear war in the Western hemisphere. The magnitude of this situation led to intensified public fears of nuclear weapons, and resulted in the realization by top government officials of the importance of slowing the nuclear arms race. During the twentieth century, advancements in military technology, like ballistic missiles, called for the transformation of foreign policy on nuclear warfare. The development of intercontinental ballistic missiles by the Soviet Union in the late 1950s made nuclear warfare possible from far-reaching locations. Parties in conflict no longer had to be in the same country, or even continent to engage in war. This added an element to the nuclear arms race and meant that foreign policy had to adapt, and expand to meet needs of scientific developments to ensure international security. The President and his administration had to turn to experts in nuclear science to form foreign policy, instead of relying on the limited nuclear knowledge from politicians. The Cuban Missile Crisis and Limited Test Ban Treaty are often approached from a strictly a historical or political perspective. Authors such as Michael Dobbs in One Minute to Midnight, recall a historical timeline of events from both the United States and Soviet Union accounts of the Cuban Missile Crisis. The historical perspective lends itself to comparing the experience of the United States to that of the Soviet Union to understand how the progression of events occurred. Paul Hammondin The Cold War Years: American Foreign Policy Since 1945, evaluates United States foreign policy, such as the Limited Test Ban Treaty, during the Cold War and compares foreign policies of different presidential administrations. This research stems from the work of Lawrence Badash, Scientists and Development of Nuclear Weapons From Fission to the Limited Test Ban Treaty, 1939-1963.2 Badash’s work approaches the Cold War by providing a brief overview from the perspective of scientists and nuclear policy from World War II until the Limited Test Ban Treaty. This research will expand on last chapter in his book on the Limited Test Ban Treaty to engage the perspective of scientists and nuclear policy with history and political science. This research serves to bridge a the gap between history, political science, and nuclear public policy by deconstructing the relationship between science and policy, the actors in international conflict resolution, and the historical significance of science during the arms race in the 1960s.In the year immediately following the Cuban Missile Crisis, President Kennedy used collaborative efforts by the Atomic Energy Commission, Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, and the Presidential Science and Technology Committee, to shape the United States position on nuclear disarmament to try and settle public fears about nuclear war. The influence of each of these actors led to the demand for a treaty to limit nuclear testing to underground, and to reduce nuclear fallout in the atmosphere. The Atomic Energy Commission ran the experiments to evaluate nuclear fallout in the atmosphere, the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency led the negotiations in Geneva for the treaty, and the President’s Science Advisory Committee communicated the information to the President and eased domestic concerns about the treaty. In the year from the Cuban Missile Crisis until the Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, the dialogues from the Atomic Energy Commission, the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, and the President’s Science Advisory Committee to President Kennedy and his top advisors, revolutionized the process of the spread of knowledge between the scientific community and politicians in the United States. This communicative partnership between these two separate spheres permitted successful negotiations of the Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, began the movement to slow the nuclear arms race, and expanded public policy to incorporate scientific actors. The Cold WarThe Cold War started at the conclusion of World War II, and was a time of political tension and military competitions between the Eastern and Western Bloc. The Eastern Bloc included the Soviet Union and its Warsaw Pact allies, and the Western Bloc consisted of the United States and their NATO allies. The conclusion of the Second World War, left President Harry Truman and Premier Joseph Stalin at odds about the development of Eastern Europe and Germany. President Truman fought for the future of Germany to have liberalism and free markets, but Premier Stalin wanted strong communist governments to help protect the Soviet Union, and Soviet invasions in Eastern Europe. This disagreement about ideologies led to the “Iron Curtain” dividing Eastern and Western Europe. To combat the spread of Soviet ideas throughout Europe, President Truman used “containment” in his Truman Doctrine in 1947. Containment was a foreign policy that was sought to prevent the spread of communism abroad. With the death of Premier Stalin and the end of the Presidency for Truman, the next stages of the Cold War were left to President Dwight D. Eisenhower and Premier Khrushchev. This time period was characterized by the rearmament of weapons between the Eastern and Western Bloc, in hopes that they would each deter the other, and the non-violent space race. The arms race was known as the “missile gap,” which referred to the estimation of ballistic missiles between the two parties.3 With the Soviet’s early advances in the space race with Sputnik 1, public fears began to sink in that the Soviets also had more advanced nuclear capabilities than the United States. False reports, inconsistent numbers, and political objectives between President Eisenhower and Senator Kennedy complicated the missile gap situation, and the fears about the “gap” remain largely invalid.4 In August of 1957 the Soviet Union test launched the first successful intercontinental ballistic missile, and ICBMs became the most important part of their nuclear weapon arsenal.5 By the end of the decade, both sides had the capabilities for “Mutual Assured Destruction,” meaning that both parties had enough nuclear power to destroy the other.6 Because of the rapid succession of nuclear warheads, very early discussions of a test ban treaty started to take place. However, discussions were halted in May of 1960 after the U-2 incident. The incident occurred when a United States U-2 spy plane was shot down in Soviet airspace and the pilot was captured. President Eisenhower and the Central Intelligence Agency were forced to admit that they had sent the plane on a spy mission over Russia.7 This incident greatly deteriorated United States relations with the Soviet Union, and intensified the arms race for newly elected president, John F. Kennedy, in 1961. The Disarmament MovementAtomic energy testing had been debated between politicians and federal agencies in the United States since the 1950s, and informal agreements among countries within the United Nations had been reached. But the agreements showed to be ineffective, because regulating underground testing proved to be a problematic endeavor. The United Nations could not distinguish underground tests form earthquakes, which meant on-site tests were necessary to make sure the agreements were being kept. The Soviets heavily opposed on-site tests, and for this reason did not want to comply with a complete nuclear test ban treaty.8 Then, after the U-2 incident, efforts for a treaty stifled as tensions worsened for the United States and Soviet Union. President-elect Kennedy promised to make disarmament negotiations for a more peaceful society a priority during his time in office. After his election, he made a movement for this promise by establishing the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency to research and negotiate with the Soviet Union, and other countries with nuclear weapon capabilities, for a comprehensive test ban. From 1953 to 1961, Fidel Castro led an armed revolt and political movement, which became known as the Cuban Revolution to overthrow the current President. Castro aligned himself with the Communist Party and sought to make Cuba a communist state. The relationship between Cuba and the United States worsened when Castro nationalized all United States property in Cuba. In retaliation, on January 3, 1961 President Eisenhower ended diplomatic relations and restricted trade with Cuba. In 1959, after the Cuban Revolution ended and Castro rose to power, Cuba began a political relationship with the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union and Cuba agreed to mutually defend each other. In 1961, the Kennedy administration launched an attempt to overthrow Castro and communism in Cuba, called the Bay of Pigs Invasion, which failed drastically. This event infuriated Castro, the Communist Party in Cuba, and the Soviet Union. To show the strength of the Soviet Union and send a message to the United States about interfering in communist countries, Khrushchev ordered ballistic missiles to be placed in Cuba, which became known as the Cuban Missile Crisis. Following President Kennedy’s address to the nation on October 22, 1962, which disclosed the military threat of Soviet missiles in Cuba, public fear about nuclear weapons was at an all time high. President Kennedy warned the nation that, “no one can see precisely what course it will take or what costs or casualties will be incurred… but the greatest danger of all would be to do nothing.”9 The frightening words from the president petrified the American people, and sparked unsettling reactions from the media during the rest of the crisis. On October 23, the New York Times headline read “U.S. Imposed Arms Blockade on Cuba on Finding Offensive Missile Sites; Kennedy Ready for Soviet Showdown.”10 The newspaper article is filled with apprehensive rhetoric, such as using the word “showdown” to describe the imminence of the conflict. The New York Times was fearfully anticipating the negotiations between the United States and Soviet Union, describing the event as a “critical moment in the cold war.”11 Ultimately, the Cuban Missile Crisis would be over in a matter of days, but for Americans who lived through the anxious thirteen days, the threat of nuclear danger was distressingly close, the two leaders of the countries’ agreed that the crisis had escalated too far and something must be done. President Kennedy was left to respond to their public, and settle their fears about the nuclear arms race by mobilizing his scientific policy-makers for a rapid disarmament treaty to change public perceptions about the threat of nuclear weapons. Five days later, on October 27, Premier Khrushchev sent the letter to President Kennedy presenting him with the negotiation terms for removing missiles from Cuba. His letter stated the willingness of the Soviet Union to remove missiles in Cuba if the United States removed their missiles from Turkey and promised never to invade Cuba again.12 At the end of his letter, Premier Khrushchev made a prolific statement that spoke to the future of both, the policy on nuclear weapons and the advancement of Soviet-American relations. He wrote, “I attach great importance to this agreement in so far as it could serve as a good beginning and could in particular make it easier to reach agreement on banning nuclear weapons tests.”13 Much like Premier Khrushchev, President Kennedy was alarmed over coming so close to engaging in nuclear war. In a White House meeting following the Cuban Missile Crisis, President Kennedy declared, “it is insane that two men, sitting on opposite sides of the world, should be able to decide to bring an end to civilization.”14 Both power leaders were confronted in the aftermath of the Cuban Missile Crisis with the realization that limits needed to be in place on the nuclear arms race to control the power of heads of state, and to control nuclear proliferation around the globe. The Cuban Missile Crisis was vastly important in changing United States foreign policy on nuclear weapons because it was the first time a major nuclear threat was made against the United States. In the 1960s, the United States was seen as a superpower, especially pertaining to nuclear weapons, because the United States was the only country to use the nuclear bomb. But when the Soviet Union threatened to send ballistic missiles from Cuba, the dangers of nuclear weapons became increasingly relevant for foreign policy in the United States. No longer did the United States have the upper hand in military technology, the Soviets became a major world power matched with nuclear capabilities. The threat of nuclear attacks pushed the United States to prioritize nuclear disarmament among countries with nuclear weapon capabilities. The Cuban Missile Crisis instilled public fears about nuclear weapons and was the event that expedited conversation among top leaders for nuclear disarmament. Just two months after the Cuban Missile Crisis, Premier Khrushchev and President Kennedy exchanged letters calling for a “cessation of nuclear tests.”15 As Premier Khrushchev put it, “it seems to me, Mr. President, that time has come now to put an end once and for all to nuclear tests.”16 But he goes on to state that they do not agree on banning underground tests, and that he considers on-site visits a violation to Soviet freedom.17 Scientific federal agencies confirmed that to in order for the Soviets to agree, and the treaty to be ratified in the near future, it would have to be a “limited” nuclear test ban treaty. They advised President Kennedy of their decision to create a treaty that would ban testing in the atmospheric, outer space, and underwater tests, in hopes that this offer would be more appealing to the Soviets.18 Although the treaty would still allow underground atomic testing, the goal was to limit nuclear fallout in the Earth’s atmosphere from the radiation from nuclear arms and to try and decrease nuclear proliferation.19 Scientific Federal AgenciesThe Atomic Energy Commission, the Arms and Disarmament Commission, and the Presidential Science and Advisory Committee were independent federal agencies that during the Kennedy administration made significant contributions to the making of the Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty. They are considered “scientific” agencies because of their work in researching and synthesizing scientific information for the President and his top advisors, and “independent” meaning they were not headed by the President or a cabinet member. Instead, the president would appoint members of the committee or commission to serve as experts in their field. Unlike other federal agencies that consisted of politicians who then later explored the issues of their agency, most of the members of independent federal agencies were already professionals in their field at their time of appointment. For example, Dr. Jerome B. Wiesner was a professor of electrical engineering at Massachusetts Institute of Technology before serving as the chairman of the Presidential Science Advisory Committee under President Kennedy. Members of these agencies played a unique role in engaging scientific research with foreign policy. The purpose of these independent federal agencies was to supply the president and executive branch with scientific reports that would help make informative decisions and shape foreign policy. The agencies intersected in politics most commonly with the National Security Council in white house meetings on international security matters. Although now each defunct or transformed in shape, the Atomic Energy Commission, the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, and the Presidential Science Advisory committee were the central actors in providing the scientific foundation for the formation and negotiation of the Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty. The members of these agencies not only performed their role in providing the scientific framework for the treaty, but also transcended their role as scientists to makers and advisors of scientific public policy. The Atomic Energy CommissionThe Atomic Energy Commission was formed in 1947, following World War II by President Truman. Their mission was to foster and control peacetime development of atomic science and technology.20 Dr. Glen T. Seaborg, professor of chemistry of the University of California at Berkley, was appointed by President Kennedy and served as chairman of the AEC from 1961 to 1971. Dr. Seaborg arrived as an expert in nuclear chemistry, and in his position as chairman, became an expert in nuclear policy.21 The responsibility of the AEC changed shaped between its creation and the beginning of President Kennedy’s term. At first, the commission was focused more on developing the United States nuclear arsenal, but by the end of the 1950s they added peaceful uses of atomic energy to their responsibilities. Dr. Seaborg and the other members of the AEC contributed to making of the Limited Test Ban Treaty by running experiments and collecting data needed to formulate a position on atmospheric nuclear testing. Before the Limited Test Ban Treaty could be negotiated and presented to the Soviet Union, public, and the Senate, the Kennedy administration had to rely on scientists to gather information on nuclear testing to solidify a position. The Kennedy Administration, the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, and the Presidential Science Advisory Committee relied largely on the AEC to conduct these tests. On December 5, 1961, Chairman Seaborg sent a letter to President Kennedy that summarizing the progress of on going tests conducted by the AEC. In his letter, Chairman Seaborg states that the results of the high altitude effects experiments need to be pushed back to July 1 in order to have accurate readings.22 But the AEC had a proposal for the President that planned to accelerate these experiments in the future to supply information to policy-makers sooner.23 When completed, these investigations would provide the definitive conclusions on nuclear fallout in the Earth’s atmospheric and assist the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency in explaining the United States position on atomic testing. This letter was written a ten months before the Cuban Missile Crisis when the United States government was still considering a comprehensive test ban rather than a limited test ban. The unwillingness of the Soviets to comply with banning underground tests would make the underground fall out tests administered by the AEC unnecessary for the Limited Test Ban Treaty, but important in understanding the effects of nuclear testing on the environment. On January 3, 1963, two months after the Cuban Missile Crisis, a White House security meeting record reviewed the scheduled tests for that year by the commission. The report indicated that the AEC would be decreasing underground tests in the next year, as a result of considering the “longer range picture.”24 Although the AEC was almost positive that the treaty would not include underground testing in the beginning of 1963, they decided slow underground testing as a result of their findings in nuclear fallout experiments. Perhaps the greatest contribution to the Limited Test Ban Treaty by the AEC was their scientific reports on the nuclear capabilities of the Soviet Union. On March 4, 1963 the commission submitted a report that included a detailed table comparison between the United States and Soviet Union’s development in nuclear technology. 25 The table showed efforts by the United States to slow their nuclear arms race, while the Soviet Union did not make efforts to do the same.26 For example, the table shows that in the United States “personnel worked on test ban treaty, and spent extended time in Geneva,”27 opposed to the Soviet Union, “no weapons laboratory people were in Geneva; there was no evidence by weapons laboratories in test ban considerations.”28 This information by the AEC revealed that although the Soviet Union had participated in test ban discussions, their nuclear technology programs continued without restriction. This informed the President, the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, and the Presidential Science Advisory Committee that the nuclear activities in the Soviet Union were not supporting their test ban discussions, and the United States was in danger of falling behind to the Soviets in the arms race. May 19 through 31, 1963, The AEC embarked on a trip to Russia to follow up on their assertions about the Soviet Union’s current state of nuclear programs. They submitted their findings and results, which Chairman Seaborg stated as “successful,” in an eighty-four-page report outlined their trip by day as they traveled to universities and institutes in Russia that were working on atomic energy. 29 Chairman Seaborg reported that the Soviet scientists were very hospitable, and that “science can successful serve as a meeting ground between the East and the West.”30 During the AEC’s time in Russia, the two sides agreed to utilize nuclear energy for peace purposes.31 After producing the comparative report in March that the Soviets were still making efforts to expand the nuclear arms race, the AEC was able to use this trip to Russia to meet with the top Soviet leaders and nuclear experts, and have them agree to change their perspective on nuclear energy to a more peaceful approach. This trip, only three months before the treaty was signed, was a critical effort by the AEC in gaining the support of the nuclear scientists in Russia. In July of 1963, only one month before the signing of the treaty, the AEC submitted their official explanations for endorsing the nuclear test ban treaty. Among the reasons were their main two: slowing the arms race, and limiting the diffusion of nuclear weapons.32 Although, the commission was still supportive of a comprehensive ban, after their trip to Russia they knew Primer Khrushchev would only agree for a limited, atmospheric ban. Compared to the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency and the President’s Science Advisory Committee, the role of the AEC was more centered on conducting scientific experiments regarding nuclear test bans, and collecting the information on the Soviet Union’s atomic energy projects to supply to the other agencies. During their trip to Russia, they did have a hand in helping the negotiations, but more prominently their contributions to the treaty were providing the scientific framework for the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency and the President’s Science Advisory Committee to negotiate the terms of the treaty. In reflecting on his time in the AEC, Chairman Seaborg was disappointed that a comprehensive test ban could not be agreed upon, but nonetheless considered his work in negotiating the Limited Test Ban Treaty, to be one of his greatest accomplishments.33 The Arms Control and Disarmament AgencyThe Arms Control and Disarmament Agency’s mission was to “strengthen the national security of the United States by formulating, advocating, negotiating, implementing and verifying effective arms control, nonproliferation, and disarmament policies, strategies, and agreements.” 34 Established by President Kennedy on September 26, 1961, only a year before the Cuban Missile Crisis, the ACDA was major part of the President Kennedy’s promise for peaceful future in international security. In his remarks on signing the bill, H.R. 9118, to establish the ACDA, President Kennedy stated, “it is a complex and difficult task to reconcile through negotiation…but the establishment of this agency will provide new and better tools for this effort.”35 As stated in their mission and in Kennedy’s remarks, the role of the ACDA was to gather the information by the Atomic Energy Commission and to negotiate the terms of the Limited Test Ban Treaty with the Soviet Union. Members of the agency were a mix of scientists, and experts in international security and defense. The ACDA was heavily involved in the meetings in Geneva, Switzerland with the United States, United Kingdom, and Soviet Union to negotiate agreeable terms for the treaty. A report from the ACDA from March to September of 1961 recorded the failed negotiations from the agency with the Soviet Union the year before the Cuban Missile Crisis.36 The United States and United Kingdom proposal to the Soviet Union was shot down by the Soviets because of their refusal to agree with on site inspections. And the ACDA was forced to go back to the United States and review their position for the treaty. On September 25, 1961 the ACDA presented a declaration of disarmament at the General Assembly of the United Nations.37 As the leaders and experts of disarmament negotiation in the world, this program set forth the principles for the negotiations in the coming years. The program stated that the negotiations should be as rapidly as possible, not harm any state, and assure international security.38 The latter would be extremely important in the coming years when the United States and Soviet Union would have to trust that the other was not testing nuclear weapons as they finalized their negotiations. The negotiation principles by the ACDA would guide the height of the treaty negotiations from the Cuban Missile Crisis to the signing of the treaty. The December 5, 1961 letter by the Atomic Energy Commission to the President summarizing the on going investigations of fallout helped the ACDA to strengthen their position on testing. On January 5, 1962 the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency released their program to explain the U.S. position on atmospheric testing.39 This program used the results collected by the Atomic Energy Commission to explain dangers of nuclear fallout and influence the necessity for a treaty. In 1962, the ACDA would work hard negotiating terms, traveling back in forth between the United States and Geneva, Switzerland. The other part of their job was to convince the public that the treaty was needed. In the summer of 1963, after receiving the news from the Atomic Energy Commission that the Soviet scientists agreed to use nuclear energy for peaceful purposes, the ACDA presented a list to the public of the reasons support the treaty, to convince the public and therefore the Senate to ratify the treaty. The list included: to “reduce the likelihood of nuclear war, discourage nuclear proliferation, create a better climate to slow the arms race, and to protect our children from exposure to nuclear fall out.”40 With help from the Atomic Energy Commission, the ACDA formed the United States position on nuclear testing and led the negotiations in Geneva for passing the treaty. The Agency worked hard in gathering information from all actors in the negotiation process including the United States, United Kingdom, and Soviet Union. Their part as negotiators left them working abroad with the Soviets more so than working closely than with the President, like we will see from the President’s Science Advisory Committee. In setting up the principles for negotiations, gathering the information from the Atomic Energy Commission, and working hard with the Soviets for two years for agreeable test ban treaty terms, the ACDA was able to be the successful mediator between the United States and Soviet Union. President's Science Advisory CommitteeThe President’s Science Advisory Committee was first established under President Truman in 1951, but ultimately started take shape under President Eisenhower. President Eisenhower reinstated the importance of the committee after the Soviet Union’s successful launch of Sputnik in 1957. Unlike the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, the PSAC was made up completely of scientists: thirteen professors and seven who worked for laboratories. The purpose of the committee was to “provide advisory opinions and analysis on science and technology matters to the entire federal government and specifically the President.”41 The mission of the committee was broadly stated to advise the federal government on science and technology issues, but from 1961-1963 the committee, especially chairman Weisner, focused their energy on assisting the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency and the Atomic Energy Commission on drafting the Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty. The role of the PSAC in the making of the treaty was communicating and discussing the progress to the President and focusing on the domestic effects of the treaty. Two months before the Cuban Missile Crisis, on August 9, 1962, Advisor Weisner sent a letter to President Kennedy addressing his, and the rest of the PSAC’s initial thoughts a “limited” test ban treaty. At this time, the Atomic Energy Commission had communicated to the PSAC that a “limited” treaty might be the more reasonable option. The committee had some concerns they wanted to be brought before the President. The first one was that not including on-site inspections in the limited treaty would set the precedent as a first step against arms control that inspections would not be implemented.42 This worried the PSAC that the Soviets would expect the same from a comprehensive test ban treaty in the coming years. At the end of the letter, Advisor Weisner stated the PSAC’s main goal for the next year. The committee would seek to answer for President Kennedy if the “advantages of such a proposal as a disarmament measure outweigh the domestic disadvantages.”43 In the next year the PSAC conferred with the Atomic Energy Commission to evaluate the domestic effects of the treaty, and specifically if the treaty would be a threat to national security. After deliberating and assessing the results of the nuclear fallout tests by the Atomic Energy Commission, the committee submitted a draft statement for the nuclear test ban treaty on August 17, 1963.44 This draft was intended to convince the president to sign the treaty, and for the President to use to help persuade the public for support for ratification. In this letter, they addressed some lingering national security concerns, such as that under the treaty weapons could still be develop just untested, which would still promote the arms race.45 Because the President’s Science Advisory Committee was concerned solely on domestic affairs, the committee took longer to convince that the treaty was in the best interest of the United States than the Atomic Energy Commission and the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency. However, in their conclusions decided to support ratification. In their final statements they wrote “in our judgment, this treaty poses no danger to our military security. Its acceptance would provide relief from radioactive fallout and contribute to…preventing the spread of nuclear weapons to other countries… an important step toward a safe and secure peace in the world.”46 After influencing the president, the next job of the committee was to gain the support of the public so the Senate would vote to ratify the treaty. On August 25, 1963 the PSAC released a statement of official support for the Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, with the Presidents approval, for the Sunday paper. In the statement they announced their strong support for the Senate for ratification, and addressed public concerns over fallout and questions about the treaty.47 The committee explained that, “the treaty would provide relief from radioactive fallout” and contribute to “preventing the spread of nuclear weapons to other countries.”48 The most important aspect of their statement was to ensure national security, “it is our judgment that the present advanced state of U.S. nuclear technology…makes it possible to accept the restrictions of this treaty with confidence in our continuing security. Although certain technical possibilities will have to be foreclosed, these limitations also apply to other nations.”49 In defensive of their approval to ban nuclear tests, the PSAC reminded the United States that the same limitations would also apply to other nations, and in this regard would slow the nuclear arms race. Through this document the President’s Science Advisory Committee was able to translate the science behind the treaty, rally the support of the public enough for the Senate’s ratification on September 24, 1963. Through their work with the Atomic Energy Commission and the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, the President’s Science Advisory Committee assisted with the passing of the Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty by briefing the president on the progression of the negotiations and by persuading the public and Senate for its ratification. Although their contributions were not as purely scientific as the Atomic Energy Commission, their responsibility of explaining the scientific analysis to the president and public was a great endeavor. The committee communicated more directly with President Kennedy, than the other agencies, and was able to work close with him to address the domestic issues surrounding the treaty. Not even a year after the Cuban Missile Crisis and one of the most turbulent times in national security in history, the President’s Science Advisory Committee was able to ensure the public that the treaty would not put the United States in danger, but would take steps to combat such incidents and promote a more peaceful world. Response From the President and RatificationAfter the U-2 incident under President Eisenhower the public was fearful and nuclear policy reform was a major political issue. President Eisenhower’s failure to pass a test ban treaty was widely criticized by Kennedy during his presidential campaign. When President Kennedy assumed the office he was adamant about making policy to please the public and making advances to a more peaceful world as part of his political platform. The influence on the President from these three scientific federal agencies in making the treaty was abundant. Similar to the President’s Science Advisory Committee, the President’s job was also to convince the public to support the treaty, but more directly by being the mediator between the federal agencies to the people. The original motivation for nuclear disarmament was pushed because of public fears, and it was President Kennedy’s job to inform the public on the negotiations for the treaty worked on in the past year. On June 10, 1963 President Kennedy gave the commencement speech at American University, which has been quoted as, “the most important speech by an American president in the last half century.”50 The President decided to deliver his speech on the relevant and momentous topic: world peace. President Kennedy was able to use the scientific research on nuclear fallout from the agencies and turn it into an emotional plea for a nuclear test ban, specifically calling for the Soviets to oblige to the treaty. In explaining nuclear fallout President Kennedy stated, “it makes no sense in an age when the deadly poisons produced by a nuclear exchange would be carried by the wind and water and soil and seed to the far corners of the global and to generations unborn.”51 He went on to discuss why he supports the treaty and how banning atmospheric test would lead to peace: “It would increase our security – it would decrease the prospects of war.”52 President Kennedy’s speech was extremely successful in gaining the approval of the public because of his ability to present peace as attainable, by passing the treaty. He used the information presented to him by the President’s Science Advisory Committee, from the Atomic Energy Commission and the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency to piece together a demonstrative speech that promoted peace and encouraged collaborative efforts with the Soviet Union. On August 8, 1963, three days after the treaty was signed, President Kennedy would send a similar message, but this time to the United States Senate calling for ratification. In his “Special Message on Nuclear Test Ban to the Senate of the United States,” President Kennedy presented many ideas that would be reiterated in the “Statement of Official Support for the Limited Test Ban Treaty” by the President’s Science Advisory Committee on August 25.53 He called for the Senate’s bipartisan support to ratify the treaty because it would inhibit the arms race, advance world peace, curb pollution, and would not halt American nuclear progress.54 On September 24, 1963, after years of research and negotiations and messages from the President and the President’s Science Advisory Committee, the Senate ratified the treaty in a vote of 80 to 19. The treaty went into effect on October 10, 1963.55 ConclusionOn October 3rd and 4th of 1963, representatives from the President’s Science Advisory Committee attended the “Ministerial Meeting on Science” in Paris, France. The meeting was put on by the Organization for Co-Operation and Development, an organization established in 1960. This meeting addressed the themes that were occurring in the early 1960s between science and politics in the United States, but at a global level. The meetings focused on problems of national science policy and the strength and success of countries measured in science and technology.56 In the representatives’ summary on the meeting, they wrote: “there results a growing role for government in scientific affairs, and a need for greater appreciation and communication among all sectors of society of their mutual tasks, attitudes, and responsibilities toward science.”57 This statement broadened the approach of analyzing how the fields influence and affect each other. In analyzing an international negotiation, such as the Limited Test Ban Treaty, it is apparent that science has a place in foreign policy, but at the Ministerial Meeting on Science, the scientists concluded that not only are a greater range of actors involved in politics, but also a greater range of actors are now engaged in science. During the entire term of President Kennedy leading up to the ratification of the Limited Test Ban Treaty, the communicative partnership with scientists and scientific federal agencies was indispensible in creating, negotiating, and drafting the treaty. Just as scientists are not experts in running political campaigns, politicians are very rarely experts in the science behind nuclear technology. But the scientists in their role as members of the Atomic Energy Commission, Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, and the President’s Science Advisory Committee became advisors in nuclear public policy. In this capacity, these scientists became world leaders and frontrunners in slowing the arms race. President Kennedy recognized and acknowledged the role of the scientists and communication with them in collaborating on scientific policy matters. In a Statement by the President on the Science Advisory Committee the president wrote of the necessity of science integrated in public policy, and the importance of communication between the scientific community and federal government. He stated, “the observations of the Committee deserves serious consideration by scientists and engineers engaged in research and development and by those administering the large Government research and development programs.”58 President Kennedy saw his Science Advisory Committee as filling a need of communication between the scientific community and government officials. The early 1960s, especially the making of the Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, saw a unique and new interdisciplinary focus in both science and politics. The scientific federal agencies under President Kennedy developed an incomparable role in foreign policy. Although today their position in the government has been transformed. The Atomic Energy Commission was dissolved in 1975, and replaced by a similar entity, the Department of Energy, in 1977 under President Jimmy Carter. The Arms Control and Disarmament Agency was merged into the Arms Control and International Security Affairs, under the Department of State in 1999. In 1972, President Richard Nixon eliminated the President’s Science Advisory Committee, and a similar organization was not developed until 2001 under President George W. Bush, the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology. The first two agencies have now been stripped of their “independent” status, now being headed by members of cabinet and conforming to relevant foreign policy needs. But the President Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, play almost an identical role as the Science Advisory Committee under President Kennedy. The legacy of the Limited Test Ban Treaty of 1963 is one of great perplexity. The United States settled for a limited test ban, after the Soviets would not agree to a comprehensive test ban. The “limited” test ban served as a measure to respond to the public that the government was taking disarmament seriously. The goal was for the treaty to serve as a preliminary measure for the comprehensive ban. But it was not until 1996 that a Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty was adopted by the United Nations, but currently lacks ratification from 8 states, including the United States, to be put into force. It is remarkable that a treaty that was fought for fervently in the 1960s is yet to be ratified in 2015. The scientists in the federal agencies deconstructed in this paper, were the driving force behind the limited treaty. With the members now being replaced by politicians, instead of scientists, there are dramatic effects in foreign policy decision-making. Most obviously seen in the prolonged efforts to ratify the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty. Regardless of the legacy and current politics on nuclear test bans, the negotiations in 1962 and 1963 hold a fundamental position in the history of United States foreign policy, for their impacts in transcending the roles of scientists and politicians, and expanding the fields of science and public policy. In Advisor Weisner’s obituary on October 23, 1994, there was a quote from a New York Times editorial that stated the advisor played “a key role in trying to work a sensible public policy out of the increasingly complex interrelationships between Government and science.”59 Most prominent in his obituary was not his Presidency at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, but being the Special Assistant to the President for Science. The accomplishments of Weisner, and the other members of the agencies who worked tirelessly to draft and negotiate the Limited Test Ban Treaty were never forgotten. As stated early, Chairman Seaborg considered his contributions to the treaty to be one of his greatest accomplishments, but he also the stated the fact that a comprehensive test ban was not passed, was a great shortcoming.60 Through this case study, it is apparent that the presence of scientists in formulating policy played the defining role in passing the Limited Test Ban Treaty, and current and future nuclear arms negotiations could benefit from following the model of the agencies and communicative partnerships of 1962-1963. ReferencesBadash, Lawrence. Scientists and the Development of Nuclear Weapons: From Fission to the Limited Test Ban Treaty, 1939-1963. Atlantic Highlands, N.J.: Humanities Press, 1995. Blanton, Thomas. "Annals of Blinksmanship,"The Wilson Quarterly, (Summer: 1997), The National Security Archives: George Washington University. Accessed October 18, 2015. http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/nsa/cuba_mis_cri/annals.htm Chang, Laurence, and Peter Kornbluh.The Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962: A National Security Archive Documents Reader. New York: The New Press, 1992. Hammond, Paul Y,The Cold War Years: American Foreign Policy Since 1945. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1969. “JFK’s Virtuoso Turn at the Bully Pulpit - US News.” Accessed November 6, 2015. http://www.usnews.com/opinion/articles/2013/06/10/jfks-virtuoso-turn-at-the-bully-pulpit. Kennedy, John F."Commencement Address at American University in Washington," June 10, 1963.Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley,The American Presidency Project. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=9266. Kennedy, John F. "Statement by the President on the Science Advisory Committee Report "Science, Government, and Information,” February 17, 1963.Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley,The American Presidency Project. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=9564. Kennedy, Robert F., and Arthur M. Schlesinger.Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis. New York: W.W. Norton, 1999. Khrushchev Communiqué to Kennedy, October 27, 1962. (Calling for Trading Cuban Missiles for Turkish Missiles) (State Department Translation). P. 197 Reeves, Richard.President Kennedy: Profile of Power, New York: Touchstone, 1994. Papers of John F. Kennedy. Presidential Papers. President's Office Files. Departments and Agencies. Arms Control and Disarmament Agency (ACDA). Papers of John F. Kennedy. Presidential Papers. President's Office Files. Departments and Agencies. Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), 1963. Papers of John F. Kennedy. Presidential Papers. President's Office Files. Departments and Agencies. Office of Science and Technology (OST), 1963. Papers of John F. Kennedy. Presidential Papers. National Security Files. Meetings and Memoranda. National Security Action Memoranda [NSAM]: NSAM 116, Instructions from President as a result of November 30 meeting re: atmospheric testing. JFKNSF-332-018. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. Papers of John F. Kennedy. Presidential Papers. National Security Files. Meetings and Memoranda. National Security Council meetings, 1963: No. 515, 9 July 1963. Papers of John F. Kennedy. Presidential Papers. President's Office Files. Press Conferences. 24 January 1963: Background materials. Papers of John F. Kennedy. Presidential Papers. President's Office Files. Special Correspondence. Bethe, Dr. Hans, 1961: November-December. Papers of John F. Kennedy. Presidential Papers. President's Office Files. Subjects. Disarmament: Nuclear test ban negotiations, 9 September 1963 meeting. Papers of John F. Kennedy. Presidential Papers. President's Office Files. Subjects. Disarmament: Nuclear test ban negotiations, April 1962-August 1963. Papers of John F. Kennedy. Presidential Papers. President's Office Files. Subjects. Disarmament: Nuclear test ban negotiations, July 1962 meeting in Moscow. Papers of John F. Kennedy. Presidential Papers. President's Office Files. Speech Files. Remarks on signing bill establishing U.S. Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, 26 September 1961. Papers of John F. Kennedy: President’s Office Files, Radio and Television Report to the American People on the Soviet Arms Buildup in Cuba, President’s Reading Copy, October 22, 1962 (National Archives Identifier: 193899). Papers of John F. Kennedy. Presidential Papers. President's Office Files. Staff Memoranda. Wiesner, Jerome B., 1962. Papers of Robert F. Kennedy. Attorney General Papers. Attorney General’s Confidential File. 6-9: Cuba: Cuban Crisis, 1962: USIA (1 of 3 folders). Paterson, Thomas G.Kennedy's Quest for Victory: American Foreign Policy, 1961-1963. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989. “U.S. Imposes Arms Blockade on Cuba on Finding Offensive Missile Sites; Kennedy Ready for Soviet Showdown.” Accessed October 28, 2015. https://www.nytimes.com/books/97/10/19/home/crisis-23.html. Walton, Richard J. Cold War and Counterrevolution; The Foreign Policy of John F. Kennedy. Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1973. Werrell, Kenneth P.Death from the Heavens: A History of Strategic Bombing. Annapolis, Md: Naval Institute Press, 2009. Endnotes

Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in History |