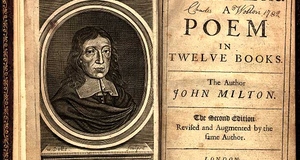

Featured Article:Comparing Godly and Satanic Happiness in John Milton's Paradise Lost

By

2016, Vol. 8 No. 08 | pg. 2/2 | « At the centre of this creation myth is the emphatic reminder that man should be ‘grateful’ and ‘acknowledge’ God from ‘whence his good descends’, with the added encouragement to direct his ‘heart and voice and eyes’ upward ‘in devotion to adore and worship God supreme’ (7.512-515). In this story, God is the figurative author of man, and man should repeatedly show signs of obeisance acknowledging this fact. As for man’s agency, he is left little when he is told that he will be ‘thrice happy’ when he is content ‘in all the earth yields’, and that he should best spend his time ‘to dwell and worship’ God and ‘multiply a race of worshippers’ (7.625-630). Through the juxtaposition of these two creation myths, we see in Paradise Lost that there is little promotion of the kind of human ingenuity that is described in Protagoras. We quickly learn from such a comparison that Milton invests much confidence in the ability of God to curb and sufficiently satisfy humanity’s hunger to make, create, and innovate. In the hands of Milton, God is presented as the great ‘nourisher’, with a power to satisfy humanity’s restlessness (5.398). This purported power can be detected in the genial features of Paradise offering the utmost variety in ‘all trees of noblest kind for sight, smell, taste’, ‘flowers of all hue’, food ‘the choice of all tastes’, and generally ‘all sorts... variety without end’ (emphasis added) (4.215, 4.254, 7.40, 7.54). The common feature in these descriptions is the capping of variety that is signified by the ever-present, all-encompassing, adjectival all, which indicates there is no room for more variation or improvement in Paradise. All of God’s subjects must be content with the variety nature offers, and they are instructed to ‘enjoy [their fill] what happiness this happy state’ can offer ‘incapable of more’ (5.503). Paradisal contentment appears unsustainable if we consider for a moment the eventual dissatisfaction Eve will experience in that ‘narrow room [of] nature’s whole wealth’ (4.207). E. M. W. Tillyard suggests such confining conditions ‘provide no adequate scope for [Adam and Eve’s] active natures’.31 This poses a problem for Milton’s message, since his portrait of beatitude sits at odds with what Tillyard calls the ‘primal requirements of the human mind’.32 When Tillyard talks of the primal he is surely referring to humanity’s drive toward perfection that would ultimately trigger Eve’s curiosity to develop methods to produce, for instance, the seedless watermelon, SPF50+ sunscreen, or synthetic contraception—all promising to facilitate a seemingly more easeful existence in her pocket of Eden. But God’s plan doesn’t allow for such human innovation. In an enlightening exercise in turning the fruits of Milton’s imagination back onto himself, Tillyard envisions that ‘Milton, stranded in his own Paradise, would very soon have eaten the apple... and immediately justified the act in a polemical pamphlet’ since ‘any genuine activity would be better than utter stagnation’.33It appears then, that the static features of Milton’s Paradise provide yet another example of the tension between the propensity of humanity to progress in its pursuit of happiness and the propensity of God to cap that potential to progress. The problem of course is revealed in Milton’s varied descriptions of God-ordained Paradise with its infinite offerings—‘I am who fill infinitude’ (7.168). The result produces a paradox that suggests any purported infinite variety in Paradise is in effect made finite by the authoring presence and perpetual prescription of a God who limits such variety. Adam comes to understand such limits in the closing book of Paradise Lost when he is ‘greatly instructed’ to ‘sole depend’ on God for the ‘fill of knowledge’ that he ‘can contain’ (12.558, 12.564). This is yet again another example of Milton deploying Augustinian metaphors to represent God as a ‘fountain of truth’ providing the primary source of satiety for his audience.34 Such a lesson for Milton’s audience leaves little freedom to seek happiness outside the limits imposed by God—who is figured as the end of perfection—which could be viewed as problematic for Milton’s project if we take into account humanity’s incessant pursuit of perfection throughout history. Malouf directs our attention to Marquis de Condorcet’s Outlines of an Historical View of the Progress of the Human Mind, which interprets history up until the late eighteenth century as a slow, intensifying ‘march of understanding’, revealing our inherent inability to recognise any ‘limits’ to our own hopes for perfection.35 Indeed, Condorcet reminds us that there will never be a limit to these hopes ‘but the absolute perfection of the human species’.36 His survey has particular relevance for our inquiry since he suggests humanity’s pursuit of perfection has always been synonymous with its pursuit of happiness. What we take from Condorcet’s study of progress is the historically informed notion that humans will always be under the dominion of an unappeased irritation to always move toward some imagined form of perfection. With this general assessment of humanity in mind, Milton’s scheme appears lacking in its failure to recognise that the limiting principles of God, and his limited offerings in nature, cannot be considered sufficient to satisfy the inherent, and arguably enduring, restlessness of humanity. We can additionally say that Milton doubly fails when his scheme instills guilt or shame in his audience—through the example of Eve—for their pursuit of perfection undertaken with the aim of attaining a version of happiness that is illusory or otherwise. Milton’s failure sits at the heart of this unresolved conflict between representations of happiness pursued obediently and disobediently within Paradise Lost. Turning to yet another permutation of such tension, we shift our focus to Milton’s well-established reputation as a champion of freedom. His defence of the civil virtues of reading have played a significant role in shaping such a reputation, especially in his urging that everyone should be given ‘the liberty to know, to utter, and to argue freely according to conscience, above all liberties’.37 Indeed, the high value Milton places on a person’s faculty of reason in their enjoyment of freedom is exemplified through the example of Eve’s correct use and misuse of such reason in the choices she makes throughout Paradise Lost. Milton reinforces this point repeatedly when he reminds his audience that ‘God [chooses] not to captivate [them] under a perpetual childhood of prescription, but trusts [them] with the gift of reason to be [their] own chooser’.38 Yet the precepts set down by Milton’s God limits the very nature and number of choices passable under the scrutiny of his audience’s well-exercised reason, since all action and thought, according to Milton, should be centred on ‘the highest perfection’ of God.39 For Milton, this steady gaze on God should lead his audience to ‘love’, ‘imitate’, and ‘be like’ God.40 In Milton’s paradox of free will, God sets the standard of action and thought, leaving humanity to direct their course within the limits of that standard. Put another way, humanity is left with the task of colouring in between the lines of a picture of life that is drawn by the creator in his colouring-in book—surely an apt vision of infancy that rebuts any claim that humans are treated as anything but children under Milton’s theology. Indeed, there is enough evidence within Paradise Lost depicting God’s supernal and terrestrial subjects as existing under the care of a guardian who is figured as their ‘parent’ and ‘eternal father’ (5.153, 7.504). Yet this aspect of existence for God’s subjects appears to be mocked by Milton’s insistence that they should see themselves as ‘lords of the world’, ‘lords of all’, and ‘over all other creatures’ (1.32, 4.288, 4.429). Herein lies another instance of that familiar conflict we repeatedly find between the will of God and the will of God’s subjects that continually escapes resolution throughout Paradise Lost and Milton’s polemical prose. All in all, we are left with an image of Milton that is riddled with a myriad of contradictions surrounding his conception of free will. On the one hand, a person’s faculty of reason is put forth as a function of the freedom that every person is entitled to enjoy under Milton’s God; yet that very faculty of reason is required to operate within the God-ordained bounds of faith, thereby limiting the essential but wandering nature of humanity in its pursuit of an illusory form of perfection promising happiness. We might better think of free will for Milton in this respect as working with blinkers that are operated first by Milton himself through his well-reasoned examples published for the education of his audience, and second by his God in the commandments of faith delivered to that audience as guides to good—albeit curbed—living. This essayby no means puts forward a meliorist approach to the general movement of humanity through history and beyond, and it certainly is not within the scope of this essay to assess the benefits or otherwise of anything that might be described as humanity’s progress. What this essay is putting forward is an interrogation of the paradox of free will that sits at the centre of a poem that claims to explain and justify the actions and commandments of a perfect but limiting God. We must remember that Milton lauds the ability of a poem to help his readers ‘apprehend and consider vice with all [its] baits and seeming pleasures, and yet abstain, and yet distinguish, and yet prefer that which is truly better’.41 But what is ‘truly better’ is dictated by Milton’s God and herein lies the paradox of free will—free to choose but only within God’s bounds. After such an interrogation we are left with the conclusion that God’s chief detractor, Satan, appears to have a sounder grasp of humanity’s restless and disobedient nature when compared to the prescriptive and hierarchical nature of Milton’s God. If posterity is considered the only true judge of a poem’s value, then it is surely the figure of Satan, and more importantly the essence of his argument quoted in introduction to this essay, that contributes to any assessment of Paradise Lost as an enduring epic carrying lasting relevance for successive generations of readers to come. Endnotes

Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in Literature |