From Cornell International Affairs Review VOL. 9 NO. 2Consequences of Iraqi De-Baathification

By

Cornell International Affairs Review 2016, Vol. 9 No. 2 | pg. 1/1

IN THIS ARTICLE

KEYWORDS

AbstractAmbassador Paul Bremer of the Coalition Provisional Authority, America's interim government between Saddam's fall and the independent establishment of a new Iraqi government, issued two specific orders during his term which combined to create a power vacuum in the weakened nation. The first order, or the De-Baathification order, eliminated the top four tiers of Saddam's Baath party from current and future positions of civil service. The second disbanded the Iraqi military. Both orders worked to eliminate the institutional memory of all Iraqi institutions, requiring Bremer to establish the nation's new government from its foundations up. This resulted in a poor security situation that ultimately allowed a strong insurgency, recruited from unemployed disaffected youth, to develop, which paved the way for the beginnings of the Islamic State in Iraq and al-Sham. IntroductionWhile the 2003 US invasion of Iraq led to the fall of abusive dictator Saddam Hussein and his Baathist party, it also contributed to the formation of a power vacuum in the weakened nation. Hussein's ousting brought the Iraqi people a chance for political freedom while also ending a stable, established regime. This Baathist government was replaced by a series of US-led reconstruction efforts ending with the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA), chaired by Ambassador Paul L. Bremer, who ran the interim organization from 21 April, 2003 to 28 June 2004. Decisions made by Bremer and other top policymakers of the Bush administration, paired with the new liberation of the Iraqi people, led to greater sectarian violence which ultimately proved catastrophic for the future of Iraq. This paper aims to outline the consequences, both direct and secondary, of the Coalition Provisional Authority Orders 1 and 2, including the De-Baathification of the Iraqi political and military institutions, in hopes of explaining the emergence of the power vacuum in the nation which worked against US reconstruction efforts. MethodologyThe research for this paper focused first on close readings of the CPA orders, specifically Order 1, 2 and 22. The inclusion of Bremer's intentions, as well as the details he chose to include in these documents provide context to the controversial orders. Order 22 was included alongside the primary Orders 1 and 2 in order to show the extent necessary reconstruction required in reinstating what was demolished by the first orders. Research then transferred to the personal memoir of Paul Bremer in order to provide an individual perspective of the events which occurred during the time that the CPA was in power. Since many analyses of the Iraq war point to a variety of conclusions, many facts and anecdotes were taken from other accounts and reorganized and reanalyzed for this paper. Additionally, interviews, both new and derived from online transcripts provide key perspectives from various military and policy leaders who were firsthand witnesses in country during the CPA's rule. Finally, some assistance for the paper's analysis was developed with assistance by discussion with National Defense University personnel. A timeline of events and a chart showing Baath/ISIS relations follow this paper in two attached appendices. The Coalition Provisional AuthorityThe Coalition Provisional Authority was the second interim US government in Iraq after the defeat and fall of the authoritarian regime of Saddam Hussein. Administrator of the organization, Ambassador Paul L. Bremer, was then presidential convoy to Iraq and was given near autonomy, answering only to President George W. Bush and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, in the reconstruction of the war-torn nation. The CPA was the organization which took over the rebuilding of Iraq from the Office for Reconstruction and Humanitarian Assistance (ORHA), the initial US humanitarian organization deployed to Iraq from 20 January, 2003 until the CPA took over that April. Lieutenant General Jay Garner provided its leadership, however the ORHA was replaced with the Department of State's CPA in hopes that a civilian body could better integrate political aspects with the reconstruction efforts. Ambassador L. Paul Bremer was a long time Department of State employee who served as a Foreign Service officer in various countries, finishing his service as Ambassador to the Netherlands under President Ronald Reagan. Upon retiring, Bremer served both as managing director of Henry Kissinger's "Kissinger and Associates" and Chairman and CEO of Marsh Crisis Consulting. Prior to returning to government, Bremer also took part in publishing multiple reports for the US federal government on Counterterrorism Strategies before and after September 11, 2001. In 2003 Ambassador Paul Bremer was approached to serve once again, this time as Presidential Convoy to Iraq and head of the Coalition Provisional Authority. While Bremer had incomparable experience as a diplomat and businessman, many argued against his placement within the CPA since he had limited experience in the Middle East. Bremer echoed this concern when describing a colleagues' credentials, "…he was one of the State Department's leading Arabists, had spent much of his career in the Middle East, and knew Baghdad well. I did not."2 Paul Bremer, other than a short tour in Afghanistan, spent little time in the Middle East and no time in Iraq. As a result, he admittedly had limitations in his knowledge of the Arabic language and culture, however he believed his experience in interagency politics, resulting from his counterterrorism work, provided him and his team more potential benefit than harm. The CPA had three main goals that Ambassador Bremer wished to accomplish before initiating the ultimate goal of handing the Iraqi government back to the Iraqi people. First, the security situation of the nation would have to be improved in order to develop stability on which to rebuild the Iraqi society. Even though official combat operations ended before the creation of the CPA, a growing insurgency intensified violence in Iraq, violence often targeting US forces. This chaos led to little remaining sense of the rule of law in the nation, causing all political progression to become dangerous until the insurgency and crime in Baghdad and throughout the nation was controlled. Second, Bremer needed to repair or rebuild the nation's infrastructure, including the government's ministries. In addition to the security issue that came as a result of the lack of law and order, widespread looting, which took place throughout Baghdad shortly after the fall of Saddam, left many government ministries and other forms of infrastructure, such as the oil refineries and power grid, destroyed. As a result of such looting, Bremer and his team had to rebuild ministry buildings from the ground up, as well as keep them and oil refineries guarded from insurgent attacks. Such attackers wished to push back the successes of the CPA in order to both tarnish the image of the "infidel" CPA and Coalition forces and push the nation into a sectarian war, allowing the Sunni Arabs to restore power. Third, Bremer and his team needed to organize a representative body which, it was hoped, would lead the country's push towards establishing a new constitution and running elections for the first time. As stated above, no power existed within the Iraqi political system that could begin to counter Saddam's Sunni Baathists. As a result, there were limited sources in which to pull new leadership from for the nation. Therefore, Bremer and his team had to travel throughout the various ethnic and religious regions in the country recruiting respected individuals who would eventually form an inclusive governing council until the nation was in a state to hold secure, honest elections. This interim body would work with the CPA in the transfer of power from the US back to Iraq, as well as draft a new democratic constitution that would ultimately be put to referendum by the Iraqi people. CPA Order 1Less than a month after the establishment of his organization, Bremer released the first of what would end up as a hundred documents aiming to reconstruct war battered Iraq. Coalition Provisional Authority Order 1 is known as the "De-Baathification of Iraqi Society," and succeeded to eliminate "Senior Party Members" from any position of civil service. It also banned them from future service in the private sector. The order defined "Senior Party Members" as those who were identified with the top 4 levels of the former Baathist party, more specifically group, section, branch, and regional command leaders. Additionally, the top three tiers of management of "national government ministry, affiliated corporations and other government institutions"3 would be intently interviewed for ties to the Baath Party, including lower member and active member tiers. Those labeled as a security risk would be removed from government employment. There is no clause in the order however that bans the 4th and 5th levels of Baath membership from future employment in government institutions. There are many reasons for Bremer to issue such an order. First, the disestablishment of any ties between the former regime and the newly sprouting Iraqi institutions would limit the possibility for Saddam's Baathists to regain power and influence in the nation. As the insurgency in Iraq began to surface, this distancing would also provide greater security for the new Iraqi government. Bremer also explained his intentions to be a response to the brutality of Saddam's former regime. The order is quoted to recognize the "large scale human rights abuses and deprivations" and note the "threat" and "intimidation"4 that the Iraqi citizens encountered at the hands of the Baathists. Bremer understands that full dissolution of the former regime and its political institutions was required to develop the desired Iraqi democratic institutions, as well as gain the trust of the Iraqi citizens. Moreover, continued Baathist stronghold, no matter how small, would have provided major security concerns for the Coalition Forces. The men of the Baath party were the same men who faced Coalition Forces during the 21 days of combat missions in Iraq during March of the same year. CPA Order 2The second order issued by Paul Bremer's organization was the CPA Order 2 or the "Dissolution of Entities." While this order was issued to dissolve all defense, intelligence, and related organizations within the Iraqi government, its primary implication was its inclusive termination of the Iraqi military, which included the Republican Guard, Navy, and Air Force.5 All chain of command, rank, title, or status which once resulted from the Iraqi military was also canceled. In addition, Bremer added any member of the military holding the rank of Colonel or above in the former regime to his past classification of "Senior Party Member," unless they were able to prove to the CPA otherwise. Finally, the order stated that all of the property once owned by these organizations was now under the authority of the Administrator, Paul Bremer himself. Ambassador Bremer's reasons to issue this order were aligned closely to those of the first order. Primarily, he feared that possible military loyalties to Saddam's regime would threaten his efforts to reconstruct the nation. How could Bremer trust individuals who just led the defense against the Coalition Forces earlier that year? Furthermore, Bremer included that, "the prior Iraqi regime used certain government entities to oppress the Iraqi people and as instruments of torture, repression and corruption."6 The Iraqi people would never begin the transition towards governmental trust if the same people who conducted themselves with brutality towards Iraqi citizens kept their positions after the fall of Saddam's regime. Political Consequences 2003-2006Longtime Iraqi president and Authoritarian Saddam Hussein was a Sunni Muslim and leading member of the Iraqi Baath party. This political party ran the nation for the entirety of Saddam's regime with an exclusive, militant, and secular doctrine. All civil and military leaders, even at the lower levels of society, were required to have membership within the party. Bremer elaborates, "Many people had joined the party because it was often the only way to get a job as a teacher or civil servant or because the person or a family member had been coerced."7 This not only led to an overwhelming majority of the Baath party in Iraq's white collar society, but the inclusion of Baath membership —which was tied to civil careers— complicated the CPA's ability to implement overarching orders of De-Baathification. The CPA had to account for the inclusion of possible Coalition supporters within the "Baath" classification, who simply identify as such for employment reasons. This muddled the De-Baathification orders, which led to the conclusion that an exception clause was needed. The Baathists, who consisted of a majority of Sunni Muslims, but a minority of the Iraqi people, held a constant hostility towards their mostly Shia Muslim citizens. Therefore, Saddam kept a strong grasp on the people of Iraq, outlawing any opposition party in order to maintain his rule. Not only did he use violence to maintain Iraqi submission, Saddam also worked to, "ensure that the Iraqi state had a secure grip on the collective deployment of violence within society."8 If Saddam loosened his hold of power, sectarian violence within the different religious sects of Iraq could escalate, ultimately endangering Saddam's rule. This authoritarianism kept sectarian tensions at bay, as Saddam's security forces would target anyone who stood up against Sunnis Islam, Saddam, or the Baath Party. The CPA Order 1 purged the Iraqi government of anyone who identified as or was tied to the upper levels of the Baath party. Therefore all senior political, military, and civil leaders within Iraq's exclusive society were removed from employment, leaving the entire top tier of Iraqi society vacant. Additionally, as CIA station chief in Baghdad, Charlie Sidell explained to Bremer: "[Y]ou will have between 30,000 and 50,000 Baathists go underground by sundown; the number is closer to 50 than to 30."9 As a result of being the only existing political party during Saddam's reign, the Baath party, although a minority, became a sizable group within Iraqi society. Therefore, the De-Baathification order isolated many employees, forcing them into unemployment. This provided the US with their first of many Iraqi subpopulations that would become disenfranchised from the Iraqi reconstruction efforts. Bremer's first CPA order also did little to help improve Iraq's already failing infrastructure. Many of the governmental leaders who were removed through the De-Baathification order came from head offices of each of Iraq's ministries. Consequently, the Iraqi government largely stalled after the order, causing all government funding, revenue, and services to halt. This combined with a great influx of looting in the streets of Baghdad which had the effect of destroying many ministry buildings and structures, ultimately made Iraqi reconstruction even more difficult. In additional to the looting of the ministries, much of the Iraq's power grid and oil infrastructure was also targeted by those looking for quick profit. This provided an even worse situation for the CPA, leaving the organization to reconstruct a wartorn, fractious nation with no governmental foundation or means of revenue. Alongside its effects on Iraqi infrastructure, CPA Order 1 also forced an overall reorganization of the Iraqi political system. While this was a primary objective of the order, its ability to demolish all of Iraq's political institutional memory was greatly underestimated. As mentioned, the Baath party was the only significant party that was legal in the country under Saddam, therefore many political opposition leaders were forced into exile during Saddam's rule. This left no opposition within Iraq who could restore order after the Baathist collapse, allowing the formation of an early power vacuum in the nation. Moreover, this vacuum could not be filled by immediate elections since no political foundation remained in the country. Bremer described the political condition of Iraq during this time stating that, "Thirty years of tyranny had gravely distorted civil administration, jurisprudence, and any semblance of representing governance. Elections and the rule of law had been a rude charade."10 If Bremer was going to succeed in the formation of a democratic Iraq, he would have to build an entirely new political groundwork, including reintroducing political parties into the nation and leading the efforts for the Iraqis to write a new constitution. Iraqi Governing CouncilBremer's strategy in forming a new Iraqi government began by recruiting the former politicians, who were exiled abroad under Saddam, to return to Iraq. This movement was ignited by what Bremer nicknamed the "Council of Exile," a group of seven former Iraqi political leaders who would provide the foundation for a new Iraqi democracy. Bremer's goal was to add to this group until it was representative of Iraqi society, containing a proportionate number of Sunni, Shia, Kurds, men, and women, and then transfer authority from the CPA to this Iraqi Governing Council (IGC). Once the group contained a representative number of around thirty members, Bremer planned to, "officially name the enlarged body the ‘interim administration' and then quickly give it ministerial power."11 It was important to Bremer and other senior US government officials to put the Iraqi government into the hands of the Iraqi people as soon as a stable enough body existed to maintain control. This would provide the entire political process with greater legitimacy in the eyes of Iraqi citizens. While the sprouting IGC clearly needed US assistance, the CPA understood that prolonged, intense US influence in Iraqi governing affairs would lead to increased anti-Coalition sentiments. This was echoed in a conversation between IGC member Dr. Ahmad Chalabi and Ambassador Bremer, where Dr. Chalabi explains how any potential slowing of a political transition to the IGC would not be a good "signal" to the Iraqi people. Bremer followed by declaring, "The president has been very clear. We will stay in Iraq until the job is done but not a day longer." Dr. Chalabi followed, "I know he [President Bush] said that. But by going slowly, you give the impression to some people that America wants to stay in Iraq."12 This exchange between the current and a future leader of Iraq reveals misunderstandings of both the political processes occurring and desired outcome. First, Dr. Chalabi, as well as the entirety of the IGC underestimated the process of reconstruction, and the necessity of a complete inclusive political body. The basic principles of democracy are new to these emerging national leaders, leading them to undervalue the importance of time in the transition of power. This time would allow the Iraqi society to develop balanced political parties, notable candidates, and a generally informed electorate, all of which took a significant span of time to blossom. Additionally, this dialogue between these leaders hinted at inconstancies relating to the overall end state of the CPA. As an experienced American politician, Bremer was well informed of the complexities of democratic governments and developed his actions aiming towards a stable Iraqi democracy. Even though Dr. Chalabi (a Shia Muslim) supported Bremer's promotion of democracy, he focused a greater bulk of his efforts towards establishing Shia dominance in the evolving political system. No matter how cooperative Dr. Chalabi was towards Bremer's plans, it would take a great deal of work on Bremer's part to help the Shia leaders of Iraq to begin mending the sectarian-fueled mistrust of their Sunni counterparts, which they developed under Saddam's rule. This glimpse of mistrust between Shia and Sunni leaders of the IGC stood as the first hint at the political "tug of war" that developed within the post invasion Iraqi government. This political stalemate within the IGC continued until 13 July 2003 when the CPA officially rolled over authority of the Iraqi state to a twenty-five person, ethnoreligiously proportionate Iraqi Governing Council. This success however did not imply an end to sectarian rivalries, as evident by the council's nine person rotating presidency which was the closest the IGC could come in a structural compromise for the position. Although Bremer's efforts regarding the IGC were met with constant friction, the organization managed to make a few leaps towards stability and order. At their first press conference, the IGC was confronted with mixed views regarding the body's ties to Western powers. For instance, Council Member Jalal Talabani, in responding to a BBC reference to the IGC as an American creature, declared, "The Council is the most representative government Iraq has ever had." In both support of and rivalry towards Talabani, fellow Council Member Nasser al-Chaderchi added, "I say this to the Arab media: stop advising the Iraqis to fight the Americans."13 This support of the US efforts in Iraq, as well as for the premise and future of the IGC, provided a sign of democratic hope for Iraq and its people. The new government was representative of its electorate, supportive of relative compromise, and proud of the change they were making for their county. This hope continued in Iraq through two elections, the second of which instituted an Iraqi governing body who, for better or worse, maintained power of the country in some sense from 2006 to 2014. Military Consequences 2003-2006While the CPA was initiating the full implementation of De-Baathification, Paul Bremer was simultaneously combatting a decreasing security situation in the nation. This increase in violence rapidly developed into an insurgency in Iraq as US military leaders and policy makers made numerous small decisions which, when combined, worked to segregate portions of Iraqi society. Upon the US invasion of Iraq, the Iraqi forces simply deserted, which allowed for quick combat operations. However, this "self-demobilization" was in part due to prior deals the ORHA made to moderate Iraqi officers; if their men resisted confrontations with Coalition forces, they would be recalled into the new Iraqi army. This promise, however, was not carried through to the CPA's administration. Bremer believed, like the Baathist party, that Saddam's Army was one of the former dictator's "instrument of repression" and therefore held the nation back from reconstruction. Franklin C. Miller, Member of Bush's National Security Council during the time of the invasion, explained the fear others had in regards to Bremer's plan. He recalls, "It was recommended to maintain the regular Iraqi army as an institution, as we believed it would be dangerous to put 300,000 men on the street with guns, without jobs."14 As feared by some within the Bush administration, the CPA Order 2 created a 400,000 man influx of newly unemployed and mostly uneducated, yet armed, men onto the already insecure Iraqi streets. These former soldiers were angry with the US's unfulfilled promises and were desperate to locate some form of income to support their families. As a result these men, who held no loyalty to the US and often very limited loyalties to their national government, simply followed financial opportunities regardless of if they supported or opposed Coalition causes. In an interview with retired Marine Colonel Clark Lethin, Assistant to the Chief of Staff of Operations for the First Marine Division during the first battle of Fallujah, he explains many instances where someone witnessed the same man assist US intelligence one day, while being paid to plant insurgent IEDs the next.15 The young men of Iraq became isolated from society after Bremer's second order and, as a result, turned towards actions in which took advantage of the security deficiencies. In addition to unanswered promises, the US did not provide adequate resources to fill the security gap that existed between the end of combat operations and the formation of new Iraqi forces. In Lessons Encountered: Learning from the Long War, a book written by the National Defense University's Institute for National Security Studies, coeditors Dr. Joseph J. Collins and Dr. Richard D. Hooker, explain, "Because there were not enough forces to occupy the entirety of Iraqi population centers, these ‘Former Regime Elements' had time and space to recover and organize their forces for a campaign against the coalition."16 Baath Party loyalists were able to take advantage of the inadequate number of troops who were stationed in country by mobilizing disgruntled "Former Regime Elements" against US forces. These hostile forces eventually spread thought Iraq, succeeding in creating an even worse security situation. General Jack Keane, former Army Vice Chief of Staff reflected, "We never made a commitment to secure the population."17 The inherent consequences of dissolving the military may have been avoided if Washington provided US commanders in Iraq with a greater number of combat units. As alluded to above, Bremer's decision to dissolve Saddam's military forces before organizing a sufficient replacement force caused a gap in the effectiveness of the rule of law in the Iraqi society. In his book Iraq: From War to a New Authoritarianism, Toby Dodge states, "There was a growing perception amongst Iraqis that, after the removal of the Baathist regime, US troops were not in full control of the situation. This understanding helped turn criminal violence and looting into an organized and politically motivated insurgency."18 The second CPA order erased the Iraqi institutions which provided security to the nation's citizens. This was paired with a newly disenfranchised and displeased population which led to increased anti-Coalition sentiments, and eventually actions. In order to combat this declining situation, Paul Bremer needed to quickly begin the long process of creating a new military. In August 2003 Bremer issued the 22nd order of the CPA, the Creation of a New Iraqi Army. When he did this, the true effect of Order 2 became clear. The 22nd order began by recalling the Army's dissolution and acknowledging the need to establish an armed body as a new institution. The order then follows to describe the basic framework of the military, from code of conduct and purpose, to rank structure and personal requirements.19 The inclusion of these rudimentary principles show how immature the organization was, and how much time and resources it would take to form the military into an effective institution. Continuing, Order 22 also establishes the new Iraqi Military as a volunteer service with a twenty-six month minimum term of office. The volunteer, and extremely short nature of these military enlistments will later prove to be a hindrance in formatting an institutional memory for the new army, as training had to stay limited and soldier turnover rates proved to be high. InsurgencyBy early 2004, the incomplete approach towards the defense of Iraqi society, stemming from the initial effects of the CPA's second order, allowed the disgruntled citizens and the expelled Baathist members to join together and refocus their efforts against Coalition forces. The first battle of Fallujah in spring 2004 marked the initial heights of the insurgency within the country. Known as the city of mosques, Fallujah provided a home for the two most intense battles of the Iraq War. As a large suburb forty-three miles west of Baghdad, Fallujah lays in Iraqi's, Al-Anbar province and provided a safe haven to former Baathists during the war. Fallujah provides an useful case study regarding Iraqi insurgency as its population is comprised of 95% Sunni Muslims, many of which turned towards violence as Coalition and Shia leaders rose in Saddam's shadow. The first battle in the city was sparked by an insurgent ambush that targeted a group of four Blackwater USA military contractors, where insurgents murdered the contractors, and hung their burned bodies from a bridge in the city. The Sunnis in Fallujah were directly affected by Bremer's order as interpreted by former CPA Military Strategist, Colonel Thomas X. Hammes, as he explained, "Now you have a couple hundred thousand people who are armed, cause they took their weapons home with them, who know how to use the weapons, who have no future and have a reason to be angry at you."20 While Hammes's analysis stands true for the entire country, it proved exaggerated in Fallujah as the quantity of both hostile personnel and hidden weapon caches located in the city soared above that of the rest of the nation. Sunni AwakeningTo combat this now overwhelming insurgency, General David Petraeus rallied for Sunni support, hoping moderate Sunni tribal leaders in Al-Anbar could be paid to provide resistance against their extremist counterparts. The need for an increased support from the often hostile sect within Iraqi society descends directly from the military void resulting from the first Iraqi army's initial disbandment. General Petraeus did not have the bodies he needed to combat the insurgency and therefore had to become creative with his acquirement of resources. Petraeus, "placed ‘local security bargains', deals between neighborhood militias and the US military, at the center of consolidating and expanding the security gains made by the US military operations."21 This concept, called the Sunni Awakening, began in the Al-Anbar province and was met with much skepticism by the international community. Many thought it counterintuitive to arm the same Muslim sect that were the least predictable in their ties to the insurgency. However, as we have already concluded, many of the low end hostile fighters were more in line with a chance for income then any ideology. Therefore, Petraeus's attempts in allying with moderate Sunni tribesmen both worked to keep moderate Sunnis engaged outside of the insurgency, and assisted to begin bridging the fracture between the Iraqi populations. If the principles of the Sunni Awakening proved effective, moderate Sunni and Shia Muslims would unite towards a common cause: defeating the insurgency. In fact this concept worked. With help from an increased US presence in the country, these Sunni tribesman assisted in forming an Iraq with the lowest rates of violence in years. This paired with the first Iraq elections in January 2005 and May 2006, began to pave the way towards a blossoming Iraqi democracy. Nouri al-MalikiOn 20 May 2006, Nouri al-Maliki was democratically elected as Prime Minister of Iraq. He was a Shia Muslim of the formerly illegal Islamic Dawa Party, who lived abroad in exile during the Hussein regime. Maliki came to office with little experience and connection to the current state of Iraqi society, due to his 24 year exile in Iran, and therefore required much mentorship from US President George W. Bush. While US officials were optimistic towards the new leader, hoping he would assist the US push towards a democratic Iraq, Maliki quickly pulled away from his initial democratic tendencies and grasped power with an increasingly authoritarian nature. Maliki entered office carrying the support of an optimistic American president who was often said to trust the leader, regardless of his lack of political experience. However, after some time in office, especially after the end of the Bush administration, the image of optimism of the new Iraqi political system started to rapidly change. From the start of his rein, Maliki faced a heavily divided Iraqi population where sectarian violence and resentment, only intensified from the first CPA order, kept the society from uniting to rebuild its struggling nation. As stated, once Saddam's Baathist regime fell, the Shia population of Iraq leaped to grasp power which they held with fear and resentment towards the Sunni population. Maliki did little to initially mend the growing sectarian rift in the nation, eventually overcompensating for his lack of experience and sectarian nation by turning towards increased authoritarianism. As the US began to give Maliki increased independence in order to begin to turn the government over to the Iraqi people, he started to act for fear of being challenged, grasping power with a rigid approach. Toby Dodge described Maliki's actions as: [F]aced with a fractured political elite consumed with infighting and self-enrichment, Maliki placed the Malikiyoun (his crony followers) at the center of a network of influence and patronage that bypassed the cabinet and linked the prime minister directly to those generals and senior civil servants who were exercising stat power below ministerial level.22 Fear of rebellion led Maliki to undo all the work of the CPA. His reinstitution of sectarian favoritism into the Iraqi "representative" government caused the invalidation of the organization, essentially causing the history of the IGC to be proven pointless. Even though Shia Muslims fill the authoritarian seat this time, the general lack of equality and compromise between the Islamic sects caused a repeat decline in political freedom and confidence parallel to Saddam's Baathist regime. Not only did Maliki lead Iraqi's political matters with crony leaders, he also altered the US built military in favor of Shia dominance. In an interview for PBS, The Gamble author Thomas Ricks stated, "Maliki gets rid of a lot of well-trained commanders in the Iraqi army and replaces them with political loyalists. It's as if he's more worried about a coup then he is in having an effective military."23 Maliki, once again afraid of challenge, traded experience for guaranteed loyalty. This isolated angry Sunni commanders as well as many Sunni followers, leading to additional fuel for the insurgency. These actions also began the eventual conversion of the Sunni Awakening tribesman from friend to foe, as the tribesman greatly resented their declining political status. These now traders against the US took the US funds and increasingly turned to align with the insurgency, eventually becoming radicalized and joining the region's various terror networks. The rise and fall of a Nouri al-Maliki would not have been likely outside of the political and military vacuums created by the CPA orders. While President Bush did trust Maliki, Bush and the rest of the US government did not have many viable non-Baathist options to head the new Iraqi government after the first CPA order. Additionally, any leader, regardless of their level of experience, would not have found easy success in Maliki's position. The chaos which was beginning to ensure in every portion of Iraqi society after the CPA's orders simply did not give Maliki a fighting chance to run his own government successfully. The overall effects of Maliki's actions ignited a civil war as the overall Iraqi infrastructure, already fractured by the actions of the CPA, could not endure further internal friction. Civil WarThe combined actions by the Sunni Awakening tribesmen and Prime Minister Maliki paved the way for deepened sectarian rifts within Iraq, a majority of such Iraq has still failed to mend. The Sunni dominated insurgency in Iraq progressively transformed into a nationwide civil war as anti-Coalition violence turned overwhelmingly sectarian, leading to a cycle of attack and retaliation between the Sunni and Shia populations. On 22 February 2006 the Al-Askari Mosque in Samarra was bombed and destroyed by what many believe to be a symbolic, religionbased attack against Shia Muslims. This event is described by some as the final event that provided the catalyst for the beginning of the outright civil war within Iraq, a concept further examined by Dr. Collins, "In February 2006, Iraq exploded in sectarian violence after the bombing of the Shiite al-Askari mosque in Samarra … Shiite militias went on the warpath after the bombing, and al Qaeda exploited the alienation of the Sunni from the Shia-dominated Iraqi government under Nouri al-Maliki."24 Since the 2003 invasion, but with extreme emphasis after the destruction of Al-Askari, Iraqi society became a battlefield of exploited opportunity. This terrorist exploitation of the sectarian disorder of Iraqi political and security structure created the foundation for the failing of the Iraqi state. Dodge adds, "[The] Iraqi state lost the ability to control its own borders, which has left Baghdad vulnerable to extended covert and overt interference from its neighbors."25 This national collapse led to an immense power vacuum which kept Iraq from securing its borders when neighboring Syria spiraled into its own internal conflict, spilling terrorist leaders across the border. Baathists and the Islamic State. While the rise of the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) has never been limited to the borders of Iraq, no matter how porous, long-term ties to De-Baathification and forced demilitarization helped provide resources and leadership for the group. This convergence between former Baathist leaders and current members of ISIS is examined by Truls Hallberg Tonnessen in an article titled, "Heirs of Zarqawi or Saddam? The Relationship Between al-Qaida in Iraq and the Islamic State." Tonnessen begins by explaining, "The top leadership of ISIS seems to have been populated by former Iraqi officers who were removed from their positions when the Iraqi army was disbanded in 2003."26 This analysis directly correlates to CPA Order 2. As noted, the Sunni leaders of Saddam's regime became isolated from the state and were pushed into radicalization, ultimately aligning themselves with the extreme ideology of ISIS. Furthermore, "Several of the former Baathist were reportedly influenced by the ideology of [al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) and ISIS] in prison. This, in combination with a shared enmity toward the Shiite-dominated regime of Nouri al-Maliki, may have facilitated cooperation and integration of AQI members, former Baathists and other incarcerated insurgents."27 Maliki's authoritarian surge worked to push away Sunni leaders, forcing them to unite with other outside radicals until all remotely related terror networks unified their efforts against the Iraqi state. ConclusionEven though combat operations in Iraq at the beginning of the US invasion were relatively straightforward, the CPA's reconstruction efforts proved overwhelmingly complex. In the name of security, Paul Bremer demolished the Baath Party and military institutions. However, this led to an outpouring of now-unemployed citizens onto Iraqi streets. Additionally, rivalries within the IGC limited the organization's effectiveness. Hope for democracy did, however, manage to emerge during the early days of 2006, but was short-lived after Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki and General Petraeus's Sunni Awakening backfired and increased the extent of sectarian violence. This violence quickly spiraled into a full-blown civil war, spreading to a regional conflict with the addition of the Syrian conflicts. Conditions continued to deteriorate, allowing the CPA-created power vacuum in Iraq to expand rapidly, allowing alienated former Baathist members to align with emerging terrorist networks. These groups grew until ISIS claimed a global caliphate in the summer of 2014. The events which followed the US invasion of Iraq stand as an omnipresent reminder that, while intentions may prove sincere, a nation's indecision toward full intellectual and material commitment to a conflict can lead to vacuums of power strong enough to inhale entire nations. ReferencesBremer, L. Paul., and Malcolm McConnell. My Year in Iraq. New York: Threshold Editions, 2006. Coalition Provisional Authority. Order 1: De-Baathification of Iraqi Society. 2003. Coalition Provisional Authority. Order 2: Dissolution of Entities with Annex A. 2003. Coalition Provisional Authority. Order 22: CREATION OF A NEW IRAQI ARMY. 2003. Dodge, Toby. Iraq: From War to a New Authoritarianism. London: International Institute for Strategic Studies, 2012. Kirk, Michael. Frontline: Losing Iraq. Documentary. PBS, 2014. Lethin, Colonel Clark, USMC. Telephone Interview. Apr. 2015. Richard D. Hooker and Joseph J. Collins. Lessons Encountered: Learning from the Long War NDU Press, 2015. Rudd, Gordon W. Reconstructing Iraq: Regime Change, Jay Garner, and the ORHA Story. Lawrence: U of Kansas, 2011. Truls Hallberg Tonnessen. "Heirs of Zarqawi Or Saddam? The Relationship between AlQaida in Iraq and the Islamic State." Perspectives on Terrorism 9, no. 4 (2015). Endnotes

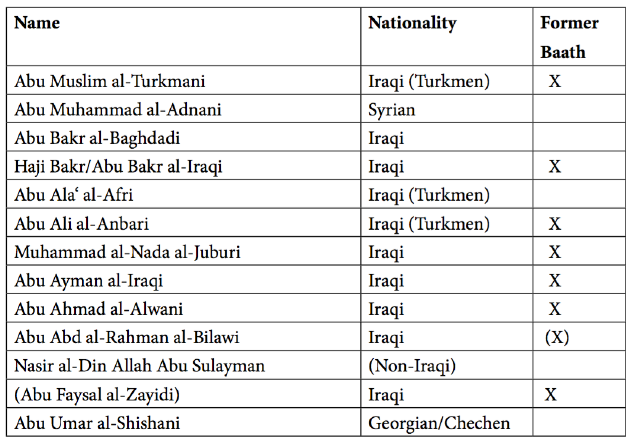

Appendix 1: Iraqi Timeline March 2003June 20142003 March 20: U.S.-led invasion of Iraq begins. 2003 April 9: Saddam’s rule is toppled and Baghdad comes under direct U.S. control. 2003 April 21: Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) is established. 2003 May 1: President Bush declares end of combat phase in Iraq. 2003 May 16: CPA Order 1 2003 May 23: CPA Order 2 2004 March 31: Four private security contractors killed in Fallujah. 2004 June 28: CPA hands over its ruling power to the Iraqi Governing Council 2005 October 15: Iraqi citizens vote for new constitution that will create Islamic federal democracy. The new constitution is approved. 2006 February 22: Al-Askari Mosque in Samarra is bombed. 2006 April 22: Nouri al-Maliki becomes Prime Minister. 2014 June: ISIS renames itself the Islamic State and declares an Islamic caliphate covering territories in Syria and Iraq. Appendix 2: Top Leadership of ISIS 2010-2014Source: Truls Hallberg Tonnessen. "Heirs of Zarqawi Or Saddam? The Relationship between Al-Qaida in Iraq and the Islamic State." Perspectives on Terrorism 9, no. 4 (2015). Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in International Affairs |