From Cornell International Affairs Review VOL. 8 NO. 1A Beautiful Mess: The Evolution of Political Graffiti in the Contemporary City

By

Cornell International Affairs Review 2014, Vol. 8 No. 1 | pg. 1/1

KEYWORDS:

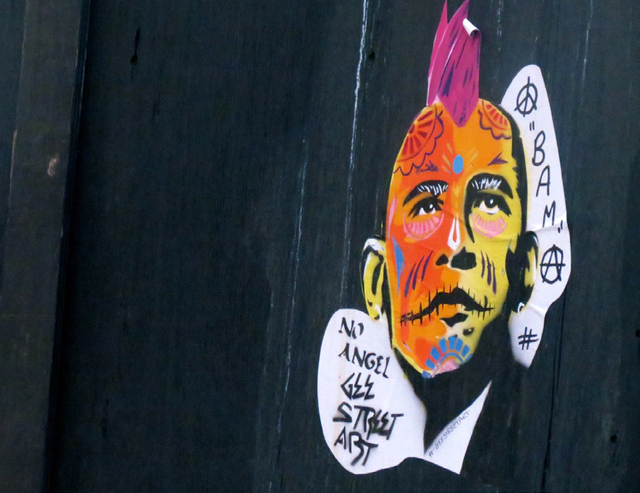

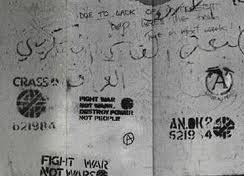

In the late 1990's the spray-painted name "Banksy" began accompanying stenciled images throughout the cities of London and Bristol, England. Taking inspiration from the anarchic messages of punk music and hip-hop graffiti popularized by New York City youth, infamous street artist Banksy began writing traditional graffiti as a teenager and eventually transitioned into image-based street art. His stenciled images were provocative, political and sharply criticized capitalism, CCTV, consumerism and war. In 2003, Banksy was at the center of global attention when he painted an image on the West Bank wall in Gaza Strip that ingeniously criticized Israel's policies towards Palestine. Banksy often culture jams by subverting advertisements, material goods or even currency to proliferate his political views. In 2004 he managed to hang a doctored Mona Lisa that depicted her with a smiley face in the Louvre. In the same year he replaced 500 Paris Hilton CDs with altered versions that read "Every CD you buy puts me even further out of your league" and printed his own satirical money with the image of Princess Diana and the headline "Banksy of England". Banksy's street art as well as his international stunts have made him popular at prestigious auctions. Christina Aguilera bought a Banksy work for £25,000 and his silkscreen print of Kate Moss sold at Sotheby's for £54,000. Because of Banksy, street art has entered the realm of high art and become extremely lucrative for those who had succeeded in the craft; in 2007, a Banksy work received a record £102,000 at auction. The unprecedented influence and commercial success of Banksy has broad implications for urban art in the contemporary city. While graffiti has traditionally been highly controversial, the advent of iconographic street art has opened new platforms for international youth to creatively express sociopolitical discontent and ultimately increased public officials' tolerance of illegal urban art.In his analysis of Banksy's street art, cultural geographer L. Dickens calls modern street art "post-graffiti" and argues that tagging "as the core component of graffiti writing, is increasingly being replaced by ‘street logos'; a shift from typographic to iconographic forms of inscription." Schacter, an ethnographer, further examines the contemporary function of street art, and after interviewing street artists, concludes that street artists ultimately seek "alternative ways of approaching public space" to make "meaningful connection to their surroundings" in pursuit of artistic expression that aims to "re-affirm the city as a place of social discussion." In an impersonal metropolitan environment, street art is a manner through which individuals reclaim territory in spaces where organic meaning and identity are obscured by logos, sociopolitical oppression or consumerism. This study aims to determine the sociopolitical motivations and implications of urban graffiti's most recent incarnation, street art, in London and in a broader international context. While graffiti has traditionally been highly controversial, the advent of iconographic street art has opened new platforms for international youth to creatively express sociopolitical discontent. Street art, or post-graffiti, is ubiquitous on the surfaces of public and private spaces in the East End of London, making it one of the graffiti capitals of the world. Walking down a dingy street, one can see the aesthetically stunning and highly visible artwork by street artists from all over the world that are often left intact by the authorities. Doors to closed businesses and public road signs are "bombed" with stickers carrying witty phrases or cartoon images. Plastic figures and cardboard cutouts of characters are up as if the streets were a gallery. Yet, rather than being perceived as purely depreciative to the area, as was hip-hop graffiti in New York City in the 1970's and 80's, street art appears to be a phenomenon that has improved the aesthetic appearance of the traditionally gritty environment of the East End and is perceived as comparatively less controversial. The international explosion of street art in global metropolises including London, Buenos Aires, Toyko, New York, Berlin, Paris and Barcelona legitimizes the question of the effect street art has on sociopolitical conditions. Street artists in the East End frequently mock political figures and society; doctored images of President Obama and Queen Elizabeth II and comical critiques of materialism appear on East End walls. At the same time, seemingly arbitrary images, posters, text, stickers and paintings take up wall space. Observing the aesthetically focused graffiti in the East End reveals that much contemporary urban art supplants literal text with visually striking iconography. This emphasis on iconography has facilitated the commercialization of street art, broadened its international audience and made it more acceptable to authorities. In contrast to the commercial success and official tolerance of street art, traditional graffiti has been less institutionally accepted. Graffiti's close ties to groups with lower socioeconomic status and Black and Latino youth has made it historically provocative. The word "graffiti" often evokes images of urban squalor and crude scrawls on dilapidated buildings or idle trains. Archetypally, a graffiti writer is a disenfranchised youth that rebels against society by spray-painting their name to claim unique space in the society that makes him or her feel invisible. In sociology, the broken windows theory asserts that markers of urban disorder, such as graffiti and broken windows, escalate over time to increased violent crime in society. This theory influences New York City's strict anti-graffiti legislation and further characterizes graffiti and street art as anti-social vandalism. Traditional hip-hop graffiti was born when youth in New York City and Philadelphia developed the practice of graffiti writing. For early graffiti writers, it was a way to claim gang territory, but many simply wanted to claim symbolic space in an alienating metropolis that systematically marginalized them. Early graffiti tags were simple; the writer's name followed by their house number. "Tracy168" was one of the most well known New York City tags. The motivating factor for youth was to "get up", or have many pieces on the streets as possible. More advanced forms of graffiti such as "pieces", short for masterpieces, the complex works done on subway trains, and "throwups", large, stylized letters, were also prevalent. Hip-hop graffiti began to disseminate from the East Coast of the United States as the visual component of hip-hop culture in the late 1970's, when European graffiti artists began writing graffiti in hip-hop style. French street artist Blek le Rat began spray painting stencil images of small rats and army tanks on Paris streets in the early 1980's after visiting New York in 1971 and witnessing the large amount of graffiti in the city. Blek began spraying New York style graffiti in France but soon began using stencil art, eventually popularizing stencil street art in Europe. As one of the first street artists, Blek's artistic skill and emphasis on aesthetics aided in the succinct articulation of sociopolitical grievances. A turn away from the traditional, text-based roots of stencil graffiti, which has its origins in the protest stencils utilized by Latin American student groups in the 1960's and Italian fascist propaganda during the Second World War, Blek's street art focused less exclusively on critical typography, but primarily on seemingly arbitrary images. Blek's iconic images of rats and tanks influenced other European street artists, drew a new distinction between graffiti and street art, and popularized a post-modern function for graffiti: to interact with and enhance the built environment. Unlike the hip-hop heritage of urban art in New York, urban art in England has strong roots in the rebellious punk rock scene of the 1970's. Lesser-known English punk group Crass, in between belting out anarchic tunes such as "Demoncrats" and "Banned From the Roxy" (quite literally), made spray paint stencils. These text-based stencils were mainly used for spreading the band's anti-consumerism and anti-establishment ideologies. Crass aimed to self-advertise and shock people out of perceived state-enforced political complacency. Putting graphic magazine collages and black stencils on the state's property were acts of rebellion. Crass was not the only punk band to integrate art and music to critique sociopolitical conditions. Successful punk rock band, The Clash, in the do-it-yourself tradition, put stencils on band t-shirts and leather jackets. These punk-crafted stencils did not go unnoticed. Jef Aerosol, one of Paris' first generation of street artists, was influenced by The Clash's stencils and began illegally spray-painting stencils in the early 1980's. It was only after street art's humble beginnings in British punk rock culture that the hip-hop graffiti style of New York—block letters, tags, and colorful "wildstyle" pieces, would become prevalent on London facades. Because the Internet was not available to expose English youth to photographs of the tags and pieces that adorned New York, this transmission of visual culture was not immediate. While hip-hop graffiti gained popularity amongst Philadelphia gangs as early as the 1960's, it was not until the early 1980's that hiphop style graffiti became widely practiced in England. Fade2, an early London graffiti writer, reflects on the nature of graffiti in his country and claims "graffiti in this country has come like a model, an airplane model. It's come here already built. Graffiti in America has taken years to develop, all the styles like wildstyle and bubble lettering. Over here we haven't added anything to it apart from brushing up on a few techniques" Ultimately, graffiti evolved in England to an entirely new form of urban art. Since the 1990's and the rise of Banksy, street art has been a popular mode of expression in London. The East End of London, traditionally the dangerous and impoverished area of London, attracts prominent street artists from all over the world to put up incredible pieces of art. As a witness to this phenomenon, it is prudent to trace the socioeconomic and political precedents for the abundance of street art in East London and examine the sociopolitical consequences street art has had on the formerly marginal space. In contrast to the grandeur of London's West End— home to Buckingham Palace, Westminster Abbey and the Houses of Parliament—the East End of London has historically been viewed as "wrong-side-of-the-tracks London". The close proximity of the East End Boroughs of Tower Hamlets and Hackney to the River Thames made the area suitable for industrial activities and trade. The 1827 opening of the St. Katherine Docks, a commercial harbor in the bustling Port of London, provided the area's population with port industry work. The Docklands, the colloquial title of the southern half of the Borough of Tower Hamlets, sustained two docks in addition to St. Katharine's and as a result received a large influx of foreign immigrants seeking work in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The arrival of these Jewish and French Huguenot immigrants intensified the problem of over-crowding. The industries also lessened the cleanliness and aesthetic appeal of the East End; tanneries and other pollution-heavy industrial trades spewed exhaust fumes and made the area generally undesirable. Poor sanitary conditions and overcrowding led to rampant disease; a cholera outbreak took over three thousand lives in 1866. Disease and poverty were synonymous with the East End and Jack the Ripper, the infamous serial killer, who allegedly disemboweled East End prostitutes in 1888. These events added to the mystique and perceived danger of London's lesser end. Tragedy would continue to strike the embattled East End Boroughs of Hackney and Tower Hamlets even into the mid-twentieth century. Targeted for its industry and proximity to three major docks in the Port of London, the East End was particularly damaged by the World War II Blitz in 1940 and 1941. The East End suffered the first of London's major bomb attacks on September 7th, 1940 and would continue to be pummeled with bombs for months. The East End District of Bethnal Green alone saw over 21,700 homes damaged. Post-blitz, the East End experienced severe population decline as many abandoned its virtual ruins; between 1931 and 1951, the population of Bethnal Green decreased by 46 percent from 108,194 to 58,353. Bethnal Green, historian T.F.T Baker chillingly observes, "Bombing had one beneficial effect in clearing slums". Another post-Blitz phenomenon was the emergence of warehouse studios and galleries in the East End. After the Blitz, comparatively lower rents and the general undesirability of the East End allowed penny-wise artists and gallerists to easily convert disused industrial spaces into galleries and studios. SPACE studios were opened by two artists near the old St. Katherine Docks in 1968 and provided studio spaces to prospective artists, increasing the concentration of artists in the East End and helping develop the East End's identity as a space for artists. Other temporary studio buildings following the model of SPACE studios were established in the East End, including ACME studios in 1972 and Chisenhale Artplace in 1980. As of 2012, there were 35 studio rental buildings throughout East London that provided studio spaces to approximately 940 artists. Remarkably, almost 3,000 artists occupied the waiting lists for these highly desirable studio spaces in 2013. Even still, an untold number of artists make work in their homes or other impromptu creative spaces. The studio rental model exists throughout England, yet in 2012 over 25 percent of all buildings dedicated to renting studio space were located in the East London boroughs of Tower Hamlets, Hackney, Greenwich, Newham and Waltham Forest. The World War II destruction of the East End and its long history of poverty and urban decline contributed to the affordability of its real estate in the late 20th century. Artists, traditionally a demographic with unstable or little income took advantage of these decaying, economical spaces as platforms for creative exhibition and aided in transforming negative perceptions of the East End. Today, the East End is a regenerating area with rising housing costs, shifting racial demographics and abundant street art. According to London-based street artist Pure Evil, the East End is experiencing rampant gentrification; old buildings are being torn down and replaced by new flats and businesses. Because of this regeneration, it makes sense for street artists to paint on dilapidated, underused buildings that will be torn down anyway. Often, street artists can simply ask a building owner if they can paint on their building. The owner will usually say yes because it adds a unique flair to their building that may attract customers. Some street artists are even hired to put up work because of the appeal of street art. Pure Evil also noted that police are less vigilant when it comes to street art in the East End. The area already is riddled with street art and it goes up at such frequency that it is time-consuming to constantly remove it. Authorities also recognize the aesthetic and economic value of free public art. Artists, traditionally a demographic with unstable or little income took advantage of these decaying, economical spaces as platforms f or creative exhibition. Famous for his enigmatic paintings of cartoon rabbits, Pure Evil makes a living by representing street artists through his self-titled gallery. He recruits street artists, brings them indoors and aids them in selling their canvases. Pure Evil Gallery displays works from international and local street artists in a tiny, bright gallery space. The lower level of the gallery purposefully resembles a rubble-ridden alleyway with dim lights and a soundtrack of haunting classical music. Pure Evil Gallery is just one of several galleries in the East End that focuses on showing and selling work done by street artists. With street artists, such as Shepard Fairey, the creator of the iconic tri-color image of Obama, moving from the streets to the galleries and achieving fame, street art has become a lucrative practice. Following a similar format to advertising, putting up a decent piece can get an artist noticed by the public and allow that artist to sell his product to a willing audience in a gallery space. It is ultimately up to the discretion of the artist to "sell out" or remain faithful to the streets. In contrast to the social disorder that researchers claimed graffiti could cause, street art, with fewer adverse class and race implications, has not hampered economic development in the East End. Following the global recession in 2008, a cluster of technology and media companies including Cisco, Facebook, Google and Vodafone established headquarters in Shoreditch, an East End neighborhood. In 2010, Prime Minister David Cameron declared this development "Tech City" and encouraged other tech-focused companies to establish headquarters there. The development of Tech City after the global recession of 2008 has ultimately encouraged greater economic growth in the East End. This painting of a woman juxtaposed with garbage and graffiti scrawls was inspiration for the title of this paper. Observing the East End, transition is evident. I witnessed an elderly Bangladeshi man make curry in his storefront window and simultaneously observed a twenty-something year-old hipster grab coffee in an independent café. A colorful and intricate piece of street art by world-renowned C215 appears next to a dilapidated park. Rotting bags of garbage and scribbled graffiti on grubby buildings lie across the street from BOXPARK Shoreditch, a new "pop-up" shopping complex that was constructed from train cars and sells generously priced clothing from trendy clothiers. Brick Lane, nearly empty during the day, is transformed into a festering ground for nightlife on Friday and Saturday and a bustling area of commerce on Sunday, the day of the Brick Lane Market. During which, blue-collar families sell inexpensive fruit while independent designers sell t-shirts for Ł35. There is a curious juxtaposition of lifestyles in the East End. On one end of the cultural spectrum lies a diverse traditional workingclass, while the other end is characterized by a controversial gentrification and a gradual influx of untraditional residents, largely students and middle to upper class, white Britons. Brick Lane, which simultaneously functions as the high street of the East End's Bangladeshi community and prime real estate for street artists, could be an anthropological case study on its own. Walking the street's course from north to south, Brick Lane progressively transitions from a blend of curry houses, council estates and convenience stores to recently opened thrift shops, newer housing developments, and cafes blasting bass and peddling Ł4 lattes. Brick Lane's transition point is the Old Truman Brewery, a gargantuan brick building that was once London's largest brewery. Since the 1990's the brewery building has been repurposed as "East London's revolutionary arts and media quarter." Walking north on Brick Lane past this bohemian mecca of office space, energetic bars and clothing boutiques, one can see how Brick Lane transforms. Public officials' tolerance of street art has been apparent in recent controversy surrounding the removal of illegal urban art. In its official graffiti policy, The Council of the East London Borough of Hackney states that it possesses no authority to remove graffiti on buildings not owned or managed by the Hackney Council. A nod to the broken windows theory, the policy states "graffiti has a major impact on people's perceptions of crime levels in a community. It is illegal, antisocial and diminishes the local environment." This policy means that graffiti removal for the majority of buildings in the Borough of Hackney is completely dependent upon the actions of the property owner or manager. The Council offers a graffiti removal service should private individuals or business owners request it—but for a fee. If building owners do not remove graffiti, they are served with a graffiti removal notice. This notice informs owners that if graffiti is not removed from their property within 14 days, council authorities will cover it with a fresh coat of paint and the owners must foot the bill. This policy was the subject of controversy when, in 2010, world-renowned Belgian street artist ROA painted a black and white rabbit on the side of The Premises Studios and Café. The recording studio/cafe combination received a graffiti removal notice from Hackney Council, despite the owner granting permission for ROA to paint a rabbit on their property. The forced removal of a piece of art that beautified a dingy street sparked outrage; over 2,000 people signed a petition demanding that the 12-foot tall rabbit remain intact. Because of the widespread public support for ROA, Hackney Council reversed its decision and allowed the rabbit to remain. By launching public campaigns in support of street art, Hackney residents pledged support for the controversial art form and encouraged the Borough's council to reconsider its indiscriminate graffiti policy. Hackney council stated "whilst it is not the council's position to make a judgment call on whether graffiti is art or not, our task is to keep Hackney's streets clean". Since graffiti as an umbrella term encompasses two distinct branches of illegal urban art: traditional graffiti and street art, which are typographic and iconographic, respectively, judging the aesthetic and cultural value of urban art invites controversy. Tension between "old guard" urban art and more recent forms of public expression including stencils, paste-ups, paintings, and even yarn installations has made simply painting over illegal public art highly controversial. Street art has aided officials' legitimatization of urban art and created new modes for encountering city space and articulating sociopolitical positions. This tension between traditional hiphop graffiti and street art has been contested in a well-publicized conflict between late graffiti writers King Robbo and Banksy. In the London Borough of Camden, a wall underneath a canal bridge was the home of a large tag done by King Robbo in 1985 that read "King Robbo." In 2009, Banksy stenciled a street art image of a man putting wallpaper over the decades-old tag. This sparked a cycle of each person painting the other's work and debate over which style was more legitimate. Banksy's symbolic painting over traditional graffiti implies a new, decorative, role for urban art in cities and a transition from hip-hop graffiti practiced by disenfranchised youth to street art done by older, less diverse groups. The debate over graffiti and street art is even relevant to elected officials, who are responsible for protecting the images of city spaces. In 2010, to quell arguments over definitions of art and vandalism, the London Borough of Sutton held a vote for residents to determine if a piece by Banksy should be covered over, in accordance with borough graffiti policy. In all, nearly 90 percent of respondents voted in favor of keeping the piece. Nevertheless, the building owner eventually removed Banksy's piece because vandals had purposely tagged it. This concrete example of street art's greater legitimacy means that, globally, individuals are turning to the respected medium and ultimately redefining traditional graffiti. Graffiti is an umbrella term that encompasses two distinct branches of illegal urban art: traditional graffiti and street art. This paper has thus far traced the evolution of street art in the East End and explored how street art has increased official tolerance of illegal urban art. The East End's regeneration and gentrification has not been hindered by street art. It's abundant, dilapidated buildings and traditional image as grimy and dangerous, influenced street artists to paint there. The mystification and ongoing gentrification of the East End has defined it as a creative, increasingly affluent and developing space. Simultaneously, street art has softened officials' intolerance of illegal urban art and opened new paths for individuals and groups to express political, social and economic grievances on public walls. Demographic measures reflect the growing popularity and affluence of the East End—the population of Tower Hamlets grew by 18 percent between 2001 and 2010 and is expected to grow faster than the whole of London for the next 11 years. Street art is an illegitimate form of artistic expression, thus street artists choose to put up work in similarly illegitimate spaces—perceived countercultural areas removed from greater affluence. Following this assertion, once a space becomes "dead" for artists, meaning gentrified and transformed by a more affluent populace, artists will move outside of that space. When will the East End exit this ongoing transition stage? Or, will it ever? At the present, there is no perceptible mass exodus of street artists from the East End; field observation in January 2013 and again June 2013 revealed an increase in the amount of art on the streets. As rents rise— central Hackney rents increased by 21 percent between 2010 and 2012, alien high-rise residencies appear in the East End, East End districts increasingly become known to Londoners as insufferable hipster enclaves, and art galleries even move westward to less expensive real estate, will street artists seek less gentrified spaces to put up street art? Even if street artists cease putting up work in the East End in search of fresher walls, the effects of street art on the East End's aesthetic appeal and global perception have thus far been largely positive; one East End resident remarked that many residents are drawn to the space because of its street art and that tourists are drawn to the area because it has essentially become an outdoor gallery. Bourgeoning economic development in the area has made it a desirable space, thus the buildings of old are being torn down and replaced by more costly housing, restaurants and boutiques. Transition is apparent in the East End, where dilapidated buildings are juxtaposed with modern shops frequented by younger (and hipper) demographics. The advent of street art has, in many ways, depoliticized urban art, specifically in Western contexts where socioeconomic gaps and social instability are less severe. My analysis of urban art in Salvador, Brazil, a space with severe socioeconomic disparity, revealed that street art and hip-hop graffiti that confronts feminism, corruption and racial and economic inequality are more common. These political images and texts are paradoxically juxtaposed onto favela slums; one month before the 2014 World Cup, graffiti writers in Salvador expressed resentment by writing "Menos copa, mais educação" (Less world cup, more education) and "Copa global? Para quem?" (World cup? For who?) on public walls. A generation of disillusioned youth have used street art as a means of public political expression. Now, policymakers can simply walk down the street to gauge popular opinion. A similar case of socioeconomic and political chaos inciting political graffiti was observed in Spain and Greece, two of the European countries most affected by the global recession. From 2008 to 2013 Spaniards experienced crippling economic recessions. These financial crises have had serious consequences for Spanish youth, including unprecedented unemployment, home foreclosure and widespread cynicism towards government. In response, many young activists and artists haven taken to the city walls, armed with spray cans, to protest the growing lack of opportunity and government corruption. By using the compelling medium of street art, youth are able to express their disillusionment directly onto city streets. A generation of disillusioned youth with limited economic and career prospects have used street art, instead of hip-hop graffiti, as a means of public political expression. Now, policymakers can simply walk down the street to gauge popular opinion. Geographer David Ley, in "Artists, Aestheticization, and the Field of Gentrification" (2001) discusses how an influx of conventional artists in Toronto neighborhoods, over time, unintentionally changed the areas from spaces of near or total poverty to affluence. Ley describes this phenomenon as "the movement of a product, and indeed a place, from junk to art and then on to commodity." In a similar manner, the evolution of urban art from "junk to art and then on to commodity" has sophisticated it as a language for voicing dissent and transformed it into a valuable art commodity. This observation is relevant to the East End, notable for its street art, and other international up-and-coming neighborhoods where street art is highly visible during and after the regeneration process. Williamsburg in Brooklyn, Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg in Berlin, The U Street Corridor in Washington D.C., Wicker Park in Chicago and Rio Vermelho in Salvador, Brazil are international examples of neighborhood regeneration being complemented by street art and public officials, in many instances, tolerating street art to appease residents and boost tourism. Ultimately, the commodification of street art and its ability to aid in the transformation of formerly dilapidated spaces unearths a new, contemporary function for street art. Street art, with its focus on images and artistry, has become a primary mode of public expression in international 8 I up-and-coming neighborhoods where street art is highly visible during and after the regeneration process. Williamsburg in Brooklyn, FriedrichshainKreuzberg in Berlin, The U Street Corridor in Washington D.C., Wicker Park in Chicago and Rio Vermelho in Salvador, Brazil are international examples of neighborhood regeneration being complemented by street art and public officials, in many instances, tolerating street art to appease residents and boost tourism. Ultimately, the commodification of street art and its ability to aid in the transformation of formerly dilapidated spaces unearths a new, contemporary function for street art. Street art, with its focus on images and artistry, has become a primary mode of public expression in international metropolises and a global language for citizens to articulate sociopolitical criticisms all the while expressing individual artistry. AcknowledgementsThis research was made possible by the generous support of the Nanovic Institute for European Studies, The Center for Undergraduate Scholarly Engagement and the Kellogg Institute for International Studies at the University of Notre Dame. References“The Art Of Punk - Crass - The Art of Dave King and Gee Vaucher - Art + Music -MOCAtv” You-Tube video, 12:17. Posted by “The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles,” 18 June 2013. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ubzKiomuUB0 Batty, David. “East End Art Galleries Forced to Go West as Local Scene dies’.” The Guardian. 07 June 2012. Accessed January 2014. Chalfant, Henry and James Prigoff. “England. “ In Spraycan Art. (London: Thames and Hudson, 1987), 7-13, 58-66. Coleman, Jasmine. “Council U-turn in Row over ROA Graffiti Rabbit in Hackney Road.” Hackney Gazette, 10 Nov. 2010. Accessed Jan. 2014 Dickens, L. “Placing Post-graffiti: The Journey of the Peckham Rock.” Cultural Geographies 15.4 (2008): 471-80. doi: 10.1177/1474474008094317. History. “East End - Land of the Cockney.” Accessed December 2013. http://www.history.co.uk/study-topics/history-of-london/east-end-land-of-the-cockney “The Flows of Prosperity.” The Economist, 30 June 2012. Accessed December 2013 Fender, Leanne. “Entire Banksy Mural Removed by Wall’s Owners.” Sutton Guardian. 11 Nov. 2009. Accessed January 2014. Field, Geoffrey. “Nights Underground in Darkest London: The Blitz, 1940–1941.”International Labor and Working-Class History 62 (2002): 13-14. doi: 10.1017/S0147547902000194 Foord, J. “The new boomtown? Creative city to Tech City in east London.” Cities, Vol. 33, (2013): 51-60. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2012.08.009 Gabbatt, Adam. “ROA’s Graffiti Rabbit Faces Removal by Hackney Council.” The Guardian, 26 Oct. 2010. Accessed January 2014. Green, C.N. “From Factories to Fine Art: The Origins and Evolution of East London’s Artists’ Agglomeration.” (PhD. diss., University of London 2001): 1968-1998. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2012.08.009 Hackney Council. “Graffiti.” Accessed December 2013. http://www.hackney.gov.uk/ew-graffi-ti-584.htm#.UsnWEmRDt2w Kelling, George R., and James Q. Wilson. “Broken Windows.” The Atlantic, 24 Oct. 2012. Accessed November 2013. Ley, David, and Roman Cybriwsky. “Urban Graffiti As Territorial Markers.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 64.4 (1974): 491-505. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8306.1974.tb00998.x Ley, David. “Artists, Aestheticization, and the Field of Gentrification.” Urban Studies 40.12 (2003): 2527-2529. doi: 10.1080/0042098032000136192. Manco, Tristan. Stencil Graffiti. New York, NY: Thames & Hudson, 2002. Print. Mathieson, Eleanor, Xavier A. Tàpies, and Glenn Arango. “Banksy,” “C216,” “Invader,” “Swoon,” “Jef Aerosol,” and “Blek le Rat” in Street Artists: The Complete Guide (London: Graffito, 2009). Millington, Val. “London 2012: What legacy for artist’s studios?” Axis Webzine, Autumn. Accessed March 2013. http://www.axisweb.org/dlForum.aspx?ESSAYID=18066 The Official Website of the City of New York. “Anti-Graffiti City and State Legislation.” Accessed January 2013. http://www.nyc.gov/html/nograffiti/html/legislation.html. Pure Evil. Personal interview. 7 Jan. 2013. Robbo vs Banksy- Graffiti Wars. Demand Media, 2012. YouTube. Demand Media, 11 June 2012. Web. 9 Nov. 2014. Schacter, R. “An Ethnography of Iconoclash: An Investigation into the Production, Consumption and Destruction of Street-art in London.” Journal of Material Culture 13.1 (2008): 35-61. doi: 10.1177/1359183507086217 T.F.T. Baker (Editor). “Bethnal Green: Building and Social Conditions from 1915 to 1945.” A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 11: Stepney, Bethnal Green (1998): 132-135. British History Online. Accessed January 2014. <http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=22753> Thompson, Nick. “Why Gritty East End Is London’s Gold Standard.” CNN, 26 July 2012. Accessed January 2014. Tower Hamlets Corporate Research Council. “Population: Key Facts: A Demographic Profile of the Tower Hamlets Population.” Ed. Lorna Spence. 4-10. Aug. 2011. Tower Hamlets Council. “Borough Statistics: Ethnicity.” Accessed January 2014. http://www.towerhamlets.gov.uk/lgsl/901-950/916_borough_statistics/ethnicity.aspx Tower Hamlets Council. “Borough Statistics: Population Growth.” Accessed January 2014. Accessed 4 January 2014 http://www.towerhamlets.gov.uk/lgsl/901950/916_borough_statistics/population University of Portsmouth: Vision of Britain Through Time. “Reports of the 1951 Census.” Accessed January 2013. http://www.visionofbritain.org.uk/census/census_page. Wacławek, Anna. “From Graffiti to Post-Graffiti.” Graffiti and Street Art. (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2011), 7-63. Yelp. “Art Galleries London: Shoreditch, Bethnal Green, Hoxton, Islington.”Accessed 2 January 2014. http://goo.gl/Fi1GDG. Map tool used to determine number of art galleries in the aforementioned districts. Image AttributionsAll photos are original work by author Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in Political Science |