Racialized Discourse and Economies of Female Saracen Bodies in The Sultan of Babylon

By

2020, Vol. 12 No. 10 | pg. 1/1

IN THIS ARTICLE

AbstractThe fifteenth-century Middle English romance "The Sultan of Babylon" partakes in the Orientalist literary tradition through the poet's linguistic economy of the Other. The paradoxical shortages and surpluses of ethnic descriptors of East female bodies suggest that the poet has consciously constructed and relies on a racialized discourse built upon the commodified Other. Viewing the Saracen woman as capital demonstrates how the female bodily otherness defines, agitates, and threatens masculine Christian identity. The politics of trade relations between Europe and the East emerge in uncanny fashions in the fifteenth-century Middle English (ME) Charlemagne romance The Sowdone of Babylone (The Sowdone). While no diplomatic transactions between Saracens and Europeans take place, peculiar, hyper-exoticized goods at times do fall into the possession of Charlemagne's men, such as Saracen princess Floripas' magic girdle that nourishes the Twelve Peers in captivity or Ferumbras' healing balm that Oliver throws into the river mid-battle.1 What Geraldine Heng refers to as the "mercantile imaginary" in the Middle Ages is instrumental to a discussion of fantasized economic benefits from the East.2 Within this mercantile imaginary, the acquired value of commodities is placed on equal footing with human agency and female sexuality, meaning that "both commodities and humans can be entered into exchange relations that yield profit for all.” In other words, all "human relations are economical." Heng considers how especially women, and even race function as commodities to be passed around, since the mercantile imagination considers otherness as "units of capital."3 Looking carefully at The Sowdone, I will consider how the mercantile imaginary depends upon a linguistic economy of the Other, especially the linguistic economy which crafts and negotiates the female Saracen body. The source of the romance's preoccupation with Oriental goods, including the exoticized female Saracen body, roots from Charlemagne's own engrossment with his oversight of interterritorial trade with Islamic empires. Gene Heck investigates the ways in which Charlemagne (742-814) navigated exchanges with the East; citing the economic historian W.C. Heyd's assertion, Heck writes that Charlemagne traded many "valuable goods borne by his ambassadors" explicitly "as enticements to develop new consumer tastes–and thereby, to produce commerce."4 Even though the literary presences of Charlemagne, the first ruler of the Romans in the Latin West who propelled medieval Europe's sense of nationalist identity, so routinely deviate from his historical person, negotiating such historical happenings with poetic action can enrich the grounds of analyses of events surrounding his literary career.5 The Sowdone, like so many other romances, is Orientalizing in the way that it expresses Charlemagne's, or more generally, the Latin West's preoccupations with Oriental goods. Edward Said's Orientalism as it applies to this discussion of trade in the Middle Ages considers how Latin Christian Europeans crafted pictures of the outside world and explores how certain understandings of distant peoples and lands were transmitted through academic studies and specific ways of thinking. Said speaks of Islam as a "lasting trauma" for Europe which began after Mohammed's death in 632, when Muslim armies had conquered Persia, Syria, Egypt, Turkey, North Africa, Spain, Sicily, and parts of France by the advent of the tenth century and then India, Indonesia, and China by the fourteenth century.6 Christian authors who lived through these conquests wrote with the intention of "controlling the redoubtable Orient" through intensified representations of Muslims, Ottoman, or Arabs in poetry and superstitions.7In light of historical accounts of Charlemagne utilizing Islamic goods to entice Europeans and to produce commerce, along with Said’s conditions of Orientalism, the poet of The Sowdone certainly partakes in this Orientalist literary tradition through a linguistic economy of the Other. The paradoxical shortages and surpluses of ethnic descriptors of the Eastern female body suggest that the poet has consciously constructed a racialized discourse built upon the commodified Other. Viewing the Saracen woman as capital helps demonstrate how the Eastern female body defines, agitates, or even threatens masculine Christian identity. Despite the unification of Floripas and the black giantess Barrok under the blanket term ‘Saracen,’ a rigid dichotomy exists between the princess’s and giant’s physical descriptions. In terms of Floripas, no physical descriptions of her occur in the text other than a few vague modifiers here and there; whereas the giantess, who appears in only one textual moment, garners an excess of ethnic descriptors which promulgate her monstrous behavior and quasi-human features. Nonetheless, this sharp contrast in physicality does not change the fact that both typologies of the Eastern female body in The Sowdone help constitute the poet’s racialized discourse which expresses the Latin West’s perceptions and fears of the East; and when such discourse utilizes aggressive Saracen women, it produces anxiety about distorted female behavior, bodily otherness in the Orient, and the realistic possibility of an infiltration of abnormal femininities into the Latin West. Politics of the Term ‘Saracen’ in Medieval Europe

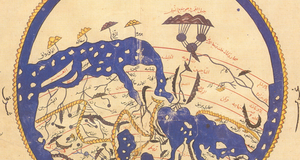

Here, the allegorical figure Lady Rectitude collates women’s marital abuse with imagined Saracen tortures of prisoners in The Book of the City of Ladies. Though Christine de Pizan’s depiction of Saracens in this moment incites terror and resentment of monstrously-depicted Eastern tyrants, in other areas of The Book, de Pizan crafts Saracen women, for instance, as admired, gentle figures whose actions merit their belonging in the City of Ladies. These varied depictions of the Other attest to the contested nature of the term ‘Saracen’ and illuminate the propensity of a Christian author to demonize and elevate the Saracen Other depending on certain criteria. For instance, Ferumbras, beloved Saracen knight in The Sowdone, is overly chivalrous and more civil than his other Saracen counterparts such as the fearsome race of giants known as the Ascopartes or Astragote, an Ethiopian Saracen giant with distorted physiognomy. Speaking to this contrasting depiction of Saracens, Siobhain Calkin points out that when Saracen knights appear too similarly to the enemy, they not only help propel an ideal of Englishness, but they dangerously underscore similarities between conflicting cultures and communities.9 By the time de Pizan cultivates her portrayals in fourteenth-century France, the word ‘Saracen’ had already acquired rich and disputed histories. Despite the term’s frequent exploitation, especially in literature, no true Saracens existed in the Middle Ages; instead, the label ‘Saracen’ is what the Latin West coined for diverse populations of peoples in the Orient.10 A term of Greco-Roman origin, pre-Islamic Arabs in late antiquity were referred to as Saracens. After the late eleventh century, however, Saracens “streamlined a panorama of diverse peoples and populations into a single demographic entity” determined by their Islamic creed.11 Most often, then, the term referred to non-Christian Arabs; but the more the Latin West utilized and villainized the Saracen Other–for reasons such as Crusade propaganda–the more inclusive the term became. At the Council of Clermont in 1095 Pope Urban II spoke of Muslims as a licentious and polluted people who, among many other demonized actions, assaulted women and terrorized Christians. Urban assured the gathered that the Holy Land was the Christians’ “rightful inheritance.”12 The frequent use and flexible criteria of ‘Saracens’ even lead to the categorization of people outside of the East as such in literature and elsewhere, meaning that attention to particular cultures was substituted for broader, often culturally inaccurate generalizations. In a plethora of medieval romance narratives, poets show ignorance to religions Muslims practiced; in Richard Coeur de Lyon, Heng underscores the poet’s incorrect characterizations of Islam in showing that the poet interchangeably uses “pagan” and “heathen” and surrounds Muslims with “Saracen idols, gods, and temples abound.”13 Meanwhile, Chaucer’s Man of Law’s Tale speaks of Scandinavians as Saracens, Lydgate’s Lives of Saints visually classifies Danes as Saracens, and the Byzantines referred to the Normans as the “new Saracens,” defining the North as Other.14 As I will demonstrate later on, The Sowdone shoves everyone outside of Christendom under the term ‘Saracen’ at moments when the Other appear in large numbers; or, as Said borrows from Gibbon, when Eastern armies appear as a “swarm of bees.”15 Geographical confusions over the Orient account for monstrous and inaccurate assumptions about the appearances of Saracen bodies. Jeffrey Cohen maintains that the term added to the overall “negative representation of difference” in the Middle Ages, making “dark skin and diabolical physiognomy” the most prominent and “familiar, most exorbitant embodiment of racial alterity.”16 Visual representations of Saracens in art and various mappae mundi often capitalize on these forms of physical alterity. The late fourteenth-century Catalan Atlas (Fig. 1), a combination of a mappa mundi and a sea-chart drawn by Jewish cartographer Cresques Abraham in Majorca, visually politicizes land based on its inhabitants. For instance, Figure 1 is a detail of North Africa, where the two largest features of this area are a black king near Timbuktu who holds a golden globe and scepter on his throne and a Muslim in a turban riding a camel. Francisco Bethencourt notes that in cartographic representations, the majority of Muslim rulers are drawn with white skin accompanied by other symbolic markers of alterity such as headdresses, elaborate clothing, and groups of animals.17 Black bodies on maps, as Thomas Hahn reminds us, “visually mark territorial distance and exoticism.”18 Interestingly enough, both the Muslim and the black king are wearing identical green tunics. Despite the differentiation in skin color, the parallel pigment of their clothing, similar size, and proximity on the map could serve as the cartographer’s identification of a wide array of peoples as Saracens. Kathleen Kelly recognizes that from antiquity to the late medieval period, many geographers expressed significant uncertainty over the exact locations of places such as Ethiopia and India, with some geographers even imagining that the two shared a border.19 As long as the Other remains clumped into this–to borrow Heng’s phrasing–streamlined panorama on maps of “human landscape,” the easier it became for the Latin West to distance themselves from the Other and see race merely as “something the rest of the world has.”20 In short, while the term ‘Saracen’ encompasses multiple populations yet often portrays such peoples as a single unit, subsets of contested depictions of Saracens manifest in art and literature, often due to authorial ignorance, confusion, discrimination, or all of the above; and these contrasting representations (i.e. beloved Saracen knight vs. monstrous dark body) are entirely dependent upon the political intentions of the Christian author. In romance too, Saracens with different skin tones from different territories are united under one militaristic force, yet simultaneously are in stark contrast with each other in terms of their morals and physiognomic features. In The Sowdone, Muslims, Ethiopians, Asians, Africans, and a fictionalized race of giants known as the Ascopartes, “some bloo, some yolowe, some blake as More” are just a fraction of the peoples which constitute Laban’s army;21 upon the news of Charlemagne’s attacks on “thre hundred thousand of Sarsyns,” Laban sends his ambassadors “to realms, provynces ferre and nere” to retrieve more personnel:22 To Inde Major and to Assye, This global assembly of Saracens in the Sultan’s empire would have troubled the medieval reader’s Orientalist observations. Here, the poet clusters foreign peoples to confront a Christian army and presents a possibility of an outcome where the fearsome Other is unable to be controlled. R.W. Southern’s assertion that Islam was the epitome of alterity for unpredictability and immeasurability couples well with this moment, since the reader cannot determine an exact number of peoples who will emerge from the Orient, or where they come from.24 Likewise, the idea of Saracens being “nere” hints at the fearsome possibility of the Other being closer than the medieval reader would wish to imagine. Additionally, this bunch of Saracen territories would have taunted Christianity’s authority and threatened European’s unifying identity due to Saracens symbolizing “the blurring of ideal boundaries” (i.e. man/animal or man/barbarian).25 When Saracens encroach upon European territory, literature like The Sowdone imagines them as monstrous, dehumanized figures who, in large numbers, are capable of unsettling the security of an unreachable Christendom. At the same time, the “sheer extent of the East enticed the aristocratic and chivalric audiences of ME romances and, accuracy aside, the author’s ability to pile up exoticized names and places establish textual credibility.26 In The Sowdone, other romances, and travel writing in the Middle Ages, an overwhelming amount of Saracen bodies are black with distorted and hybrid physiognomy. Indeed, not all Saracens subject to the Sultan Laban can be as beloved or redeeming as the knight Ferumbras, whose superlative chivalry remains constant pre- and post-conversion. Contrary to this more ‘positively-depicted’ Saracen, in his fourteenth-century travel memoir The Travels of Sir John Mandeville, Mandeville portrays the people of Ethiopia as “men of dyuers shappis” who have four feet and sacrifice their children’s blood in front of idols.27 The Sowdone’s quasi-human Astragote “of Ethiop” is the epitome of a monstrous Saracen: supposedly “a develes sone,” Astragote is described as a “kinge of grete strength” with a boar’s head and skin “black and donne,” who is born to cause Christians pain.28 His hybrid black body terrifies but also captivates; for even when the Latin West showed an awareness of the variety of Muslim skin colors, in fantasies about Muslim bodies, Christians routinely imagined the skin as dark as the traditional Ethiopian.29 When the poet of The Sowdone writes that Astragote’s skin is not just black, but “black and donne [dark],” dealing this Saracen double categorizations of darkness not only enhances his black flesh, but also conjures up the belief that black pigmentation could signal spiritual darkness. Jean Devisse’s observes that “blackness as a hermeneutic” flourished in Western Europe in place of real interactions with black peoples; yet there is a distinction between theological discourse which pins black as the color of sin and actual medieval hostilities toward black physiognomy.30 However the Ethiopian was overwhelmingly considered, as Heng puts it, a “symbolic construct of personifying sin,” marking the population by their blackness which “blazoned to all Christendom their innate sinfulness.”31 The Ethiopian body served a special hermeneutic purpose in a variety of textual spaces, such as the renowned letter exchanges between twelfth-century theologian Peter Abelard and prioress Heloise. In these writings, Abelard offers her spiritual counsel through an Ethiopian woman’s body, which Thomas Hahn in his work on textual representations of color and race in the Middle Ages sees as a classical and contemporary reading of the Song of Songs:32

Disorder and hideousness characterize the Ethiopian’s “exterior appearance” and thus overshadows the purity found in her white “bones and teeth”; even though sin does not infect her internal state in the way that it does to devilish Astragote in The Sowdone, Abelard nonetheless contributes to the negative discourses of blackness since not only does he insist that her skin exiles her “in this life” on earth, but also since he, pinning a subtly erotic gaze on her, fantasizes about her predestined transformation from black to white in the afterlife. The giantess Barrok in The Sowdone, another distorted black body among the Saracens, serves an even darker hermeneutic purpose than Abelard’s Ethiopian. Even Barrok grins “like a develle of helle,” which decays her teeth and suggests that the poet imagines even her white, “lovelier” tissue as dark and sinful.34 Conversion to Christianity often grants dark-skinned Saracens in medieval literature the opportunity to exchange their sin and blackness for white bodies. After the Sultan in the fourteenth-century ME romance The King of Tars forsakes his faith at the request of his Christian wife, his skin transformation occurs at an instant: “That on Mahoun leved he nought / For changed was his hewe.”35 A common trope in romance, the transformation from dark to light assimilates newly converted peoples into Christendom. Yet a significant number of Saracens in literary productions are white from the outset and therefore do not depend upon Christianity for their light complexions. In examining discourses of bodily diversity in the late Middle Ages, Suzanne Akbari observes how white, attractive, European-looking Saracens appear alongside darker, more monstrous ones; the light and “well-proportioned” Saracens are never subject to the same amount of resentment and destruction as the dark and distorted bodies.36 In The Sowdone, no matter how violently the Saracen princess behaves, she ends up marrying a chivalrous Christian while the dark and devilish giantess falls victim to the Twelve Peers’ murderous attack. Additionally, a Saracen’s white body becomes eroticized in crusade romances through its potential to be liberated by conversion. The Sowdone’s poet never specifies the skin color of pagan Floripas, but in the original twelfth-century chanson de geste Fierabras, she is a blonde, attractive, light-skinned princess, and her whiteness makes her more appealing to Christian knights as a potential marriage partner.37 A preoccupation festers also in Chaucer’s The Knight’s Tale with Ypolita and Emelye’s racial alterity, affirms Dennis Britton, who finds that their white skin and noble status conceal their Amazonian alterity. He even compares Ypolita and Emelye to “the white Saracen princess that Christian knights find so desirable in crusade romances.”38 Why then does the poet of The Sowdone settle for a complete omission of descriptions of Floripas’ physiognomy if her white skin could have provided such a straightforward feature to eroticize? The princess’ train of “fayrest” Saracen maidens certainly accumulate a variety of physical descriptors of their gleaming pigmentation, which Floripas even eroticizes as she markets her women to Roland, her selling point being their skin “white as swan.”39 Indeed, Floripas is the only Saracen woman in this romance with undeciphered skin color, yet she marries Guy and inherits a kingdom. Since the romance does not execute any eroticization of Floripas’ skin, I will explore how her body participates otherwise in the linguistic economy of the Other operating within the text and how her lack of descriptors challenges a classical postcolonial interpretation of a Saracen princess. Linguistic Economy of Saracen WomenFor their genders and otherness, The Sowdone engages thousands of women in what Heng refers to as the ‘mercantile imaginary.’ Recalling this concept, the mercantile imagination requires human relations to serve economic purpose, meaning that commodities, human agency, and especially female sexuality, intertwine to benefit all who deal the exchanges. Through the poet’s linguistic economy of otherness, or in other words, the poet’s semantic system in place to exploit and exoticize difference, the commodified women participate in exchange relations with outcomes that satisfy and terrify the medieval reader and Christian men in the romance. Between the ten thousand Christian “maidyns fair of face” put to death by the Sultan, the aggressive, shockingly independent Saracen princess Floripas, her train of maidens, and the ill-favored giantess overpowered by Charlemagne’s army, men maneuver these bodies with personal and political intents.40 Of these featured females, Floripas and the giantess actively partake in violence and attempt to monopolize control of their bodies. Their belligerence fails repeatedly, but when their hostilities breed success, masculine Christian identity is jeopardized, thus resulting in panic over abnormal Eastern femininities.41 An examination of the ways in which the linguistic economy of the female Saracen body functions in The Sowdone requires careful attention to these bodies in action and bodies in the poet’s descriptions. In the sixteenth-century Castilian rendition of Fierabras, Floripas appears gentle and fairly passive.42 In the original twelfth-century chanson de geste, Akbari classifies the princess as vicious yet still the “exquisite object of men’s admiration.”43 Her ME persona is particularly abnormal, since readers neither know the reality of her physical appearance nor the true motives behind her manipulation and hostility. Due to the few descriptors the poet grants her in The Sowdone along with the harsh nature of her interactions with Christians and Saracens, I would argue that she is certainly an “object,” but never receives enough verbal validation from those around her to be exquisitely admired. In lieu of admiration, she invites repulsion through moments when she stabs a jailer, confidently speaks up against religious authorities, shoves her governess out the window, starves and nourishes her prisoners, and markets her body as well as her maidens’ to reputable knights.44 Although the mastermind behind the eventual Christian triumph over her father’s forces, she utilizes her regal authority to standardize abnormal femininity while terrified chivalrous knights must surrender to her unfeminine behavior. Ethnic descriptors flood the lines for every Saracen woman besides Floripas; however, the few modifiers the poet repeatedly employs to describe the princess’ persona not only help decipher her unusual agency, but also demonstrate how she plays her part in the poet’s linguistic economy. Three times in the text other men refer to her as “free.”45 Before Laban catches on to his daughter’s schemes against him, in a proud declaration, addresses her as “My doghtir dere, that arte so free.”46 Just ten lines later, the poet recalls a conversation between Floripas and Roland, proclaiming that she “was both gente and fre.”47 When Floripas approaches her prisoner, “Duke Neymes” to confide in him her love for Guy, the poet labels her as “that mayde fre.”48 The ME word free carries over twelve different senses, and in the most general senses, Floripas is “fre” due to her “social status of a noble” and because she is “not in captivity.”49 The troubling operation of Floripas’ agency in the text reveals how her commodified body lives up to numerous definitions of both the medieval and modern senses of free. Molding Floripas to a variety of the ME meanings of free aids the poet in concretizing his racialized discourse, a discourse which propels fantasies and horrors of an uncanny amount of Eastern female freedom in commercialized scenarios. Floripas seizes control of the mercantile imagination’s exchanges of female otherness and enters female Saracen bodies in the romance’s marriage market for free. Floripas’ religious status remains in flux for a lengthy period in The Sowdone; from the moment she renounces “Mahoundes laye” until her ultimate baptism, she floats between Islam and Christianity.50 Namely, considering one definition of “fre” which indicates a release “from an oath or obligation,” for more than half of the narrative she is “fre” from committing herself to one religion–– a prolonged accentuation of her hybridity.51 Akbari sees this phase in the narrative as Floripas being “in the process of assimilation into Western Christian normative modes of behavior, which intersects with normative modes of feminine behavior.”52 Viewing Floripas’ identity in the midst of this process indicates that she does not quite attain complete assimilation until the romance’s conclusion, making this transitional period key in amplifying and freeing her alterity. Certainly carrying a “privileged status” as a Sultan’s daughter, her classification as a free maiden, according to the MED, could grant her exemptions from more than just her religious obligations.53 The poet’s descriptions constitute a liberation of her agency to maneuver beyond certain expectations typically placed on noblewomen; and based on her decisions, whether or not she utilizes this liberation to her advantage is unchallenged. Arguably some of her most gruesome actions are when she stabs her father’s jailer “with the keye cloge that she caught” so violently that “the brayne sterte out of his hede than” in order to overtake surveillance of the prison, or when she watches the Christian knights she holds captive burn alive King Lukafere of Baghdad.54 Perhaps the most sardonic sense of the ME “fre” Floripas fits is her freedom from confinement, the antithesis of the Christian knights she retains in Laban’s tower. Despite her self-declared Christian identity and her generosity toward Charlemagne’s imprisoned personnel, Floripas does manipulate and demand dreadful ultimatums, which is how she manages to monopolize the economy of Saracen female bodies in the text. Interestingly enough, white Saracen skin does not seem sufficient to satisfy the Christian knights, since they hand Floripas more rejections than acceptances when she markets Eastern bodies to them, even when the women’s pigmentation is “white as swan.”55 Floripas offers herself and her maiden’s bodies for free, yet still no man wants their bodies, troubling the romance ideal of the desired white-skinned Saracen body. In the midst of her brother Ferumbras’ battle with a member of the Twelve Peers, Ferumbras renounces his faith for Christianity, but insists that Oliver marry his sister: “Thou shalt be a duke in my contre…To my sustir shaltowe wedded be–.“56 In fact, Oliver avoids this marriage comment altogether, replying vaguely with “And of my strokes shaltow more fele / Er I to the shalle yelde me.”57 The significance of this refusal in particular lies in the fact that Oliver maintains the denial of her body despite the offer coming from another man. This detail not only obscures the mercantile imaginary where female sexuality routinely functions as a major unit of capital to be passed around, but also reveals that the men wholeheartedly resent the female Saracen body for what it is, and not who the offer comes from. The inclination for Charlemagne’s men to reject her body under any circumstance traps them into a deadly scenario. While Floripas secretly nurtures her father’s prisoners during her time as jailer, she presents a marriage proposal to Guy moments after gazing upon him. Swearing that she has loved him “many a day,” Floripas declares she will “for his love…christened be / And lefe Mahoundes laye.”58 Her confidence in securing this marriage roots from her authority as warden; she commands for Duke Neymes to “Spekith to [Guy] now for me” and reminds the men that if Guy refuses her offer, “Of you askape shalle none here.”59 Out of instinct, Guy denies the proposition because he refuses to marry someone unless chosen by Charlemagne; but Guy’s response results in a desperate economic negotiation between the Twelve Peers:

As Floripas watches this debate nearby, Guy is trapped in a scenario where he has no choice but to surrender to peer pressure and consent to the hardship ad maius bonum. The only way for all of the troops to yield profit is through Guy’s interracial union with the commodified Other. Guy’s stubbornness and delay in agreement along with the other knights’ taunts constitute a visual representation of a prevailing resentment of Eastern female bodies. Upon the news of his consent, Floripas continues to self-commodify as she announces to her new husband “Myn herte, my body, my goode is thyn.”61 Continuing her economic bargaining of female Saracen bodies in the text, Floripas presents her maidens as free “goode[s]” to the imprisoned Twelve Peers. After Floripas and her captives have driven the Sultan out of his empire, in a rapturous celebration she insists that the knights “take [their] sport” with her “thirti maydens lo here of Assye, / The fayrest of hem ye chese.”62 In this case, the knights’ responses to her offer are omitted, leaving no trace of the men’s levels of satisfaction or aversion to the Asian women. More explicitly though, Roland rejects one of Floripas’ proposals later, which sheds light on the standings of white-skinned Eastern physiognomy in The Sowdone:

Roland’s harsh rejection of the Saracen body indicates that religious convention still has a place in this text despite the surplus of moments which disregard it, such as Floripas’ physical intimacy with Guy long before her baptism. While Floripas is not troubled by the possibility of a pagan-Christian union delaying or even lacking conversion altogether, anxiety of a dissolution of religious difference through sexual intercourse is ventriloquized through Roland. In an open declaration that such intercourse would be “myscheve,” he not only hints at the transgression of Floripas and Guy’s hybrid intimacy, but he also suggests that engagement with the Eastern female body engenders sinful and supernatural (“cursed”) consequences. As expected then, Roland rejects Floripas’ fantasy of eroticized Oriental whiteness since, as Britton points out, “eroticized whiteness becomes a not-yet-realized racial sameness,” but this sameness is never realized until after conversion and marriage to European knights.64 Among her many attempts at bodily exchanges, Floripas (and the men who negotiate for her) rarely triumph in successful transactions. However, we should not measure Floripas’ agency in the linguistic market of bodies by her number of failures, but by the level of danger her one prosperous transaction potentially brings to the supposed stability and purity of Christian identity. Her own commodified body, with its whiteness never confirmed and overall absence of ethnic descriptors, unites with Guy, inherits all of Spain, and by default becomes the country’s producer of heirs. Her freedom, aggressive behavior, and undescribed physicality amalgamate to generate readerly anxiety about the King and Queen’s reproduction of potentially hybrid heirs of a Christian empire. The Giantess, Princess, and Hybridity AnxietyBarrok, the ferocious giantess whose femininity is physically antithetical to Floripas’, garners a multitude of ethnic descriptors to make her physicality impossible to overlook. When speaking of the dichotomy of Saracens who are “white, well-proportioned, and assimilable,” and those who are “dark-skinned…deformed…and doomed to destruction,” Akbari references Jaqueline de Weever’s assertion that clarifies how white Saracens embody the East’s wealth and allure when black Saracens represent the Orient’s “strangeness and horror.”65 The murder of Barrok’s spouse Alagolofure, also a giant, prompts Barrok’s aggressive entrance into the battle scene and results in her own death at the hands of Christians.66 A “cursede fende” who grins “like a develle of helle,” Barrok “did the Cristen grete distresse.”67 Upon her death, the poet comments on the foul nature of Barrok’s production of an entire giant race, expressing gratitude that “might she never aftyr ete more brede!”68 Barrok’s giant babes are a product of Alagolofure’s dark Ethiopian skin and animal anatomy bred with the giantess’ devilish facial features and noticeable size: “Richarde, Duke of Normandy, / Founde two children of sefen monthes oolde, / Fourtene fote longe were thay.”69 Richard and Charlemagne attempt to rescue and convert these babes, who soon die from a lack of their mother’s milk. Coincidentally the discontinuation of this giant family takes place right before Charlemagne hands over Spain to Guy and Floripas. Due to Floripas’ undetermined skin color and likewise a potential hybrid union between the now rulers of Spain, how much should we align Floripas’ marriage with the monstrosity of this giant family? The presentation of an entire giant race’s extinction right before a Saracen-Christian assimilated marriage signifies a potential, immediate reincarnation of Saracen monstrosity infiltrating the Latin West. The romance’s conclusion does leave the state of Spain under Guy and Floripas undetermined, which reinforces the possibilities that Floripas could in fact be dark-skinned and thus produce dark Christians. No matter how many giants the Christian armies murder, their body count of Saracens in battle, or how many brides they convert, the prosperity of the undecipherable Floripas breeds anxiety of the cyclic Saracen encroachment upon a race united in Christendom. As Akbari identifies, the Latin West’s attempts to define the Orient and Islam are merely indirect ways of defining themselves.70 Yet the poet’s limited definition of Floripas limits how much Western Christians can see themselves in her; therefore, the medieval reader is left with a choice to assume the simple assimilation of Floripas, or ponder a darker ending. Despite the romance’s system of lack and surplus in ethnic descriptors – meant to visually distinguish Floripas from other more monstrous Saracens like Barrok and her children – in the poet’s linguistic economy, the function of their bodies produce similar if not identical typologies of readerly anxiety concerning racial hybridity and tyrannical female Saracen authority. Such similarities and absence of Floripas’ physicality render a postcolonial interpretation of female Saracens more ambivalent than expected. As I’ve shown before, at times, neither Floripas’ eagerness to convert to Christianity nor the white skin of her pagan maidens are enough to sell themselves as ideal marriage partners to the Christian knights, complicating the trope of the fair-skinned Saracen princess always functioning as the object of desire on what Edward Said refers to as the “Orientalist stage.”71 In no way am I suggesting that the dichotomy of black and white Saracen bodies always evokes similar readerly responses or that the poet places the body of the giantess on equal footing with the princess. Black bodies are overwhelmingly subject to more monstrous portrayals and harsher realities than the assimilated light-skinned Saracen bodies in medieval English literature; the eventual prosperity of Floripas and sudden deterioration of Barrok speaks for itself. I am pointing to how the poet’s racialized discourse enters the commodified female Other into a trade system in which the goods can be both revered and feared, and how one abnormally “fre” Saracen woman monopolized the mercantile imaginary’s exchanges of female sexuality and inserted herself into a Christian marriage without explicitly meeting any of the prerequisites traditionally expected of her race in romance. ReferencesA. Grinberg, “The Lady, the Giant, and the Land: The Monstrous in Fierabras,” in eHumanista 18 (2011), 186-192. C. de Pizan, The Book of the City of Ladies, (transl.) E.J. Richards (New York: Persea Books, 1998). D.A. Britton, “From the Knight’s Tale to the Two Noble Kinsmen: Rethinking Race, Class and Whiteness in Romance,” in postmedieval 6.1 (2015), 64-78. E. Said, Orientalism (New York: Penguin Classics, 2003). F. Bethencourt, Racisms: from the Crusades to the Twentieth Century (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014). “fre,” Middle English Dictionary (MED), quod.lib.umich.edu/m/middle-english-dictonary. G. Heck, Charlemagne, Muhammed, and the Arab roots of capitalism (Berlin: de Gruyter inc, 2006). G. Heng, Empire of Magic: Medieval Romance and the Politics of Cultural Fantasy (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003). G. Heng, The Invention of Race in the European Middle Ages (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018). J.J. Cohen, “On Saracen Enjoyment: Some Fantasies of Race in Late Medieval France and England,” in Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 31.1 (2001), 113-46. J.J. Cohen, “The Body in Pieces: Identity and the Monstrous in Romance,” in Cohen (ed) Of Giants: Sex, Monsters, and the Middle Ages (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999), 64-95. J. de Weever, Sheba’s Daughters: Whitening and Demonizing the Saracen Woman in Medieval French Epic (New York: Garland, 1998). J. Mandeville, Mandeville’s Travels: Texts and Translations (London: Hakluyt Society 2010). K. Cawsey, “Disorienting Orientalism: Finding Saracens in Strange Places in Late Medieval English Manuscripts,” in Exemplaria 21.4 (2009), 380-97. K.A. Kelly, “’Blue’ Indians, Ethiopians, and Saracens in Middle English narrative texts” in Parergon 11.1 (1993), 35-52. L.F. Cordery, “The Saracens in Middle English Literature: A Definition of Otherness,” in Al-Masaq: Islam and the Medieval Mediterranean 14.2 (2002), 87-99. M. Uebel, “Unthinking the Monster: Twelfth-Century Responses to Saracen Alterity,” in J.J. Cohen (ed) Monster Theory: Reading Culture (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996), 264-91. P. Hardman and M. Ailes, The Legend of Charlemagne in Medieval England: Matter of France in Middle English and Anglo-Norman Literature (Cambridge: D.S. Brewer 2017). R.W. Southern, Western Views of Islam in the Middle Ages (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1962). S.B Calkin, “The Perils of Proximity: Saracen Knights, Sameness, and Differentiation,” in F.G. Gentry (ed) Saracens and the making of English identity: the Auchinlek manuscript (2005), 13-60. S.C. Akbari, Idols in the East: European representations of Islam and the Orient, 1100-1450 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2009). T. Hahn, “The Difference the Middle Ages Makes: Color and Race Before the Modern World” in Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 31.1 (2001), 1-37. The King of Tars, (ed.) J.H. Chandler (New York: TEAMS online, 2015). The Sowdone of Babylone, (trans) Alan Lupack (New York: TEAMS online, 1990). Endnotes1.) The Sowdone of Babylone, (transl.) A. Lupack (New York: TEAMS Texts online, 1990. Floripas first offers the Twelve Peers her magic girdle and calls it “a medycyne in my thoughte” (2301), and Oliver throws Ferumbras’ beloved balm into the river at line 1185. 2.) G. Heng, The Invention of Race in the European Middle Ages (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018), p.334. 3.) Ibid, p.334. 4.) G. Heck, Charlemagne, Muhammed, and the Arab roots of capitalism (Berlin: de Gruyter inc, 2006), p.181. 5.) P. Hardman and M. Ailes, The Legend of Charlemagne in Medieval England: Matter of France in Middle English and Anglo-Norman Literature (Cambridge: D.S. Brewer 2017), p.1. 6.) E. Said, Orientalism (New York: Penguin Classics, 2003), p.59. 7.) Ibid, p.60. 8.) C. de Pizan, The Book of the City of Ladies, (transl.) E.J. Richards (New York: Persea Books, 1998), p.119. 9.) S.B Calkin, “The Perils of Proximity: Saracen Knights, Sameness, and Differentiation,” in F.G. Gentry (ed) Saracens and the making of English identity: the Auchinlek manuscript (2005), p.14. 10.) J.J. Cohen, “On Saracen Enjoyment: Some Fantasies of Race in Late Medieval France and England,” in Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 31.1 (2001), p.121. 11.) G. Heng (2018), p.111. 12.) Ibid, p.114. 13.) G. Heng, Empire of Magic: Medieval Romance and the Politics of Cultural Fantasy (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003), p.80. 14.) L.F. Cordery, “The Saracens in Middle English Literature: A Definition of Otherness,” in Al-Masaq: Islam and the Medieval Mediterranean 14.2 (2002), p.89, K. Cawsey, “Disorienting Orientalism: Finding Saracens in Strange Places in Late Medieval English Manuscripts,” in Exemplaria 21.4 (2009), p.384, and F. Bethencourt, Racisms: from the Crusades to the Twentieth Century (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014), p.56. 15.) E. Said (2003), p.59. 16.) Cohen (2001), p.114. 17.) F. Bethencourt (2014), p.55. 18.) T. Hahn, “The Difference the Middle Ages Makes: Color and Race Before the Modern World” in Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 31.1 (2001), p.11. 19.) K.A. Kelly, “’Blue’ Indians, Ethiopians, and Saracens in Middle English narrative texts” in Parergon 11.1 (1993), p.36. 20.) G. Heng (2018), p.35. 21.) The Sowdone of Babylone (1990), 1005. 22.) Ibid, 1004, 996. 23.) The Sowdone of Babylone (1990), 999-1003. 24.) R.W. Southern, Western Views of Islam in the Middle Ages (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1962), p.4. 25.) M. Uebel, “Unthinking the Monster: Twelfth-Century Responses to Saracen Alterity,” in J.J. Cohen (ed) Monster Theory: Reading Culture (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996), p.268. 26.) L.F. Cordery (2002), p.90, 88. 27.) J. Mandeville, Mandeville’s Travels: Texts and Translations (London: Hakluyt Society 2010), p.458-59. 28.) The Sowdone of Babylone (1990), 352, 356, 353, 347. 29.) J.J. Cohen (2001), p.119. 30.) G. Heng (2018), p.185. 31.) Ibid, p.185. 32.) T. Hahn (2001), p.23. 33.) The Letters of Abelard and Heloise, (ed and trans) Betty Radice (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1974), p.138-39. 34.) The Sowdone of Babylone (1990), 2946. 35.) The King of Tars, (ed.) J.H. Chandler (New York: TEAMS online, 2015), 938-39. 36.) S.C. Akbari, Idols in the East: European representations of Islam and the Orient, 1100-1450 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2009), p.156. 37.) Ibid, p.156. 38.) D.A. Britton, “From the Knight’s Tale to the Two Noble Kinsmen: Rethinking Race, Class and Whiteness in Romance,” in postmedieval 6.1 (2015), p.65. 39.) The Sowdone of Babylone (1990), 2086, 2749. 40.) The Sowdone of Babylone (1990), 226. The Sultan kills the Christian maidens out of pride and in the heat of militaristic vengeance, declaring immediately after that he will “distroie over all / The sede over all Christianite,” 234-35. 41.) My claim about readerly anxiety is informed by Cohen’s acknowledgement that romance authors “believed that they could have a formative, even transfigurative effect on their audiences,” which transforms romance into a “culturally engaged practice.” J.J. Cohen, “The Body in Pieces: Identity and the Monstrous in Romance,” in Cohen (ed) Of Giants: Sex, Monsters, and the Middle Ages (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999), p.79. 42.) A. Grinberg, “The Lady, the Giant, and the Land: The Monstrous in Fierabras,” in eHumanista 18 (2011), p.188. 43.) S.C. Akbari (2009), p.175. 44.) The Sowdone of Babylone (1990), 1601, 1516, 1580, 2301, 2081. 45.) The Sowdone of Babylone (1990), 1615. 46.) Ibid, 1615. 47.) Ibid, 1628. 48.) Ibid, 1884. 49.) “fre,” Middle English Dictionary (MED), quod.lib.umich.edu/m/middle-english-dictonary. 50.) The Sowdone of Babylone (1990), 1896. 51.) “fre” (MED). 52.) S.C. Akbari (2009), p.175. 53.) “fre” (MED). 54.) The Sowdone of Babylone (1990), 1606-08, 2015. 55.) Ibid, 2749. 56.) Ibid, 1223, 1225. 57.) Ibid, 1229-30. 58.) The Sowdone of Babylone (1990), 1891, 1895-96. 59.) Ibid, 1897, 1900. 60.) Ibid, 1919-24. 61.) The Sowdone of Babylone (1990), 1929 (emphasis added by me). 62.) Ibid, 2085-87. 63.) Ibid,2747-54. 64.) D.A. Britton (2015), p.65. In The Sowdone, Floripas’ maidens all undergo Christian baptism at the same time as she does (The Sowdone of Babylone (1990), 3192), which finally identifies the maidens’ whiteness as a desirable feature to constitute this newfound “racial sameness.” 65.) S.C. Akbari (2009), p.156, 160. For more information on de Weever’s insight, see her Sheba’s Daughters: Whitening and Demonizing the Saracen Woman in Medieval French Epic (New York: Garland, 1998). 66.) In most adaptations of Fierabras, the giant Estragote defends the bridge for Laban and is married to Barrok. However, in The Sowdone, Estragote is killed off earlier in the romance, and the giant defending the bridge is named Alagolofure, who seems to be married to Barrok, yet the poet claims that Barrok is Estragote’s wife. Whether a scribal error or intentional, in most scholarship this confusion is either not addressed or scholars refer to her as Astragote’s wife. In my analysis I assume her marriage to Alagolofure. 67.) The Sowdone of Babylone (1990), 2945-53. 68.) Ibid, 2955. 69.) Ibid, 3019-21. 70.) S.C. Akbari (2009), p.280. 71.) E. Said (2003), p.66. Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in Literature |