Featured Article:The Horn of Africa: Critical Analysis of Conflict Management and Strategies for Success in the Horn's Future

By

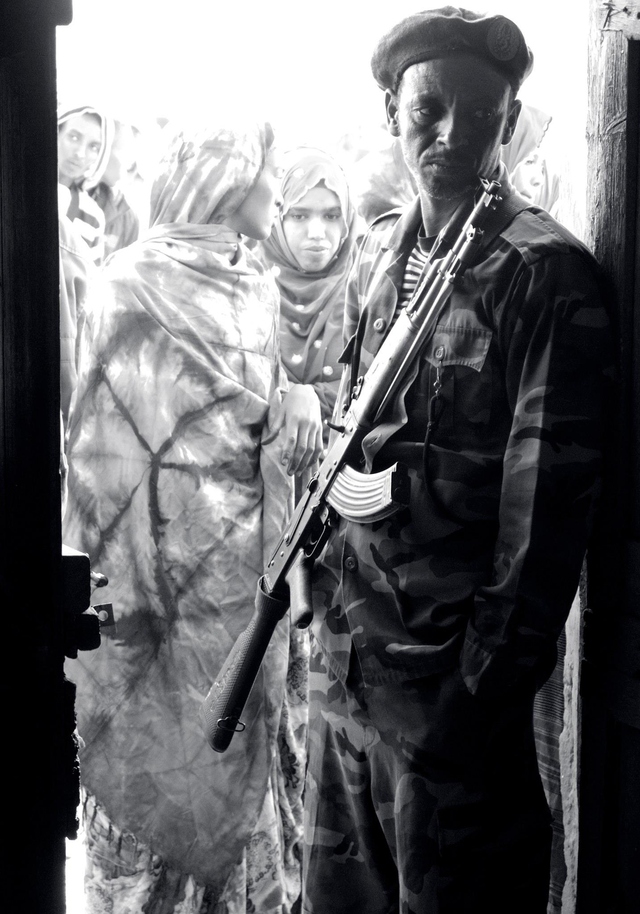

2010, Vol. 2 No. 06 | pg. 1/6 | » Conflict management in the Horn of Africa has been relatively unsuccessful. Foreign colonialism created boundaries that have yet to be resolved, and newly independent nations engaged in conflicts responsible for human rights atrocities, child conscription, and collapse of state infrastructure. Cold War superpower intervention did little more than arm opposing parties with millions of dollars in military weapons that continue to propagate violence and death. Oppressive regimes rise and fall in the form of communist juntas, dictators, and rivaling militias, warlords, and clan leaders. Mediation of conflicts in the Horn occurs locally, regionally, and through the international community. Each form requires different communication strategies that must be implemented to be successful. Local conflict management requires communication channels to be easily accessible and frequently utilized. States that communicate often tend to be more rational in their policies toward one another because aims are better defined and have less chance of being unresolved or misunderstood. However, the Horn’s nations hardly promote communication. Little is said between nations before action occurs and even less is communicated mid-conflict. When negotiations do occur, parties are typically accusatory, and more than once parties have walked out on negotiations.To be sure, frequent communication is best face to face; it fosters trust and negotiation through mediation instead of violence. Unfortunately, the culture of the Horn is characterized by distrust and suspicion, so regional intervention has been necessary. Usually regional intervention offers rivaling states a third party’s good offices. These services must be offered by a mutually trusted, neutral agent otherwise arbitration will fail. Often, third parties will simply provide a neutral location for negotiations to occur. Locations that are biased toward one party or the other will immediately put the visiting party in a defensive posture and can limit the efficacy of collaborative talks before they begin. Third parties may also perform an inquiry to establish the facts of the dispute and subsequently offer acceptable solutions. Regional third parties have acted in the Horn, but resulted in little success for reasons to be later examined. In this region, third parties must be carefully selected; mediators have been difficult to designate due to alliance swapping, perceptions of illegitimate representatives, and a deep-rooted cultural adherence to war, deception, and distrust. A soldier stands in the doorway of a polling station in Somaliland, an internationally unrecognized region of northwestern Somalia that has nevertheless acheived a modicum of stability relative to neighboring Somalia. November 2012, photo © Dustin Turin. Finally, conflict management is conducted through the international community. Various nations have influenced the Horn, including the colonial powers of Britain, France, and Italy, later replaced by the Cold War superpower influence of the United States and the Soviet Union. The United Nations has attempted interventions since the early 1990s, most notably through peacekeeping. Peacekeeping is strictly defined as UN troops physically separating two sides after an armed conflict and is not meant to be enforcement or collective security. UN peacekeeping in the Horn developed into peace enforcement, which resulted in disaster for the United States and the UN immediately following the fall of Somali dictator, Siad Barre. Later examination will suggest that intervention by the international community is a primary reason for continued conflict in the Horn. Total conflict resolution in the Horn may be chimerical, but conflicts can be successfully managed if diplomatic strategies focus on opening political space through communication between leaders of nations, factions, militias, and clans. In Ethiopia and Eritrea, the boundary has yet to be demarcated, and the political elite push their agenda through violence. Minimal communication between nations suffocates political space, and people living on the border are forced into violent action. In Somalia there is also little room for dissention, but the problem there rests on the validity of representatives. Peace conferences have previously excluded certain groups, and the resulting backlash was often violent. Opening a forum for all parties to actively communicate could negate the winner-take-all mentality, and allow diplomacy to be effective. However, political space can allow peaceful dissent only if it is simultaneously promoted with public accountability and representation. HISTORICAL ANALYSIS OF STATE CONFLICTThe Horn of Africa is known for being riddled with conflict. The great northeastern shield of Africa is comprised of Somalia, Ethiopia, Eritrea and Djibouti, and conflict persists in all four nations. The disagreements between these nations are longstanding and complex, described as first a clash of tribes, then imperial consolidation and foreign colonialism. Once independent, these expectant nations desired to test their newfound sovereignty, which was complicated by superpower support during the years of the Cold War. Violence continued through revolution, fractured militia competition, and a failed state. To understand the progression of the Horn’s conflicts, colonization of the region must first be examined. ColonialismThe Horn of Africa, not including Ethiopia, was colonized at the end of the nineteenth century between the French, British, and Italians. Djibouti was designated French Somaliland in 1885; British Somaliland included the region of the Gulf of Aden, and Italian Somaliland included control of the region nearest the Indian Ocean, as well as the Red Sea colony of Eritrea. In Ripe for Resolution, I.W. Zartman suggests Ethiopia’s expansion eastward into colonial Somaliland necessitated the boundaries that were established through European agreement in 1897. The British eventually demarcated their frontier in 1932-34 by joint agreement, but the Italian boundary was never demarcated. In an effort to claim more territory, the Italians launched an invasion against Ethiopia under the pretext that the Ethiopians were within Italian Somaliland. In fact, the Ethiopians were within their own border, but the invasion effectively moved the Somali boundary westward to include the grazing area of the Ogaden, an Ethiopian portion of the Horn of Africa. Subsequently, the Ogaden was returned to Ethiopian administration. However, the boundary became a barrier to nomadic migration. This was an unacceptable proposition for the Somalis, and a border dispute between Italian Somaliland and Ethiopia followed. Despite negotiation, arbitration, and mediation, little was resolved. This Italian Somali-Ethiopian border dispute was a direct result of colonialism in the region. Borders imposed on Somalia and Ethiopia were something that the “Somali nomads had neither needed nor encountered before” and were ambiguously assigned, hung on non-existent points, or established around nomadic tribe and clan territory (1985 p.75). This resulted in tensions between two nations that both relied on a common region for nomadic survival. The Ethiopians were “arguing a legal case over where the border was, and the Italians [were] arguing a social-moral case on behalf of the Somalis over where the border should be” (1985 p.76). The Ethiopians were justified to claim the territory by law, and the Somalis were convinced of their claim through colonial power support. Despite Italian support, colonial Somaliland gained nothing from the dispute. Somali bitterness toward colonial rule led to independence movements that resulted in a united Somalia by 1960. This newly emergent state of Somalia was comprised of tribal leadership and had no continuity for central governance. Consequently, tumultuous power struggles ensued and the development of relationships between bordering nations created conflict as the new state struggled to establish its identity in the region. States that must develop fundamental structures of their relationships, compared with altering established relationships, have difficulty maintaining order because their diplomatic process has no continuity. In the border dispute between Somalia and Ethiopia, the nations were forced to develop a new system of interaction because of the formation of boundaries and creation of the Somali state. This claim is also observable in Eritrea’s call for independence from Ethiopia. When Ethiopia’s government changed from a traditional empire to that of a military junta, a new form of negotiation was forced to occur, and the conflict grew in complexity. The following section examines the conflicts associated with independence movements in the region.Continued on Next Page » Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in International Affairs |