Fatherhood Socialization of Masculinity Through Parental Involvement in Youth Sport

By

2019, Vol. 11 No. 10 | pg. 1/1

IN THIS ARTICLE

KEYWORDS

AbstractFathers often use sport to socialize their sons into masculinity. When coaching their own son in a sport, men must juggle their own desire to win with their son’s enjoyment. This paper examines the types of masculinity in coaching, while integrating theories of parental participation and involved fathering. As identified with mixed research methods, inclusive masculine fathers have better father-son relationships than orthodox masculine fathers. Techniques used by inclusive masculine fathers were studied through qualitative interviews; they often delegate their own son to other coaching fathers in order to maintain a positive father/son relationship Men often promote masculinity in fatherhood. This paper investigates how fathers use sport to teach masculinity to their sons and how this affects the father-son relationship. Coaching is a popular way to promote masculinity; in youth sports, fathers often coach their own kids. Gottzén and Kremer-Sadlik (2012) show this topic’s relevancy by examining how fathers juggle masculinity when coaching youth sports (Gottzén and Kremer-Sadlik 2012). This research considers the changing roles of modern fatherhood, and how this relates to the roles sports serve in father-son relationships (Graham, Dixon, and Hazen-Swann 2016). This general question began the research: How do fathers use sport to promote masculinity, and how does this affect father-son relationships? This general question stemmed from three specific questions regarding fatherhood, parenting, and masculinity:

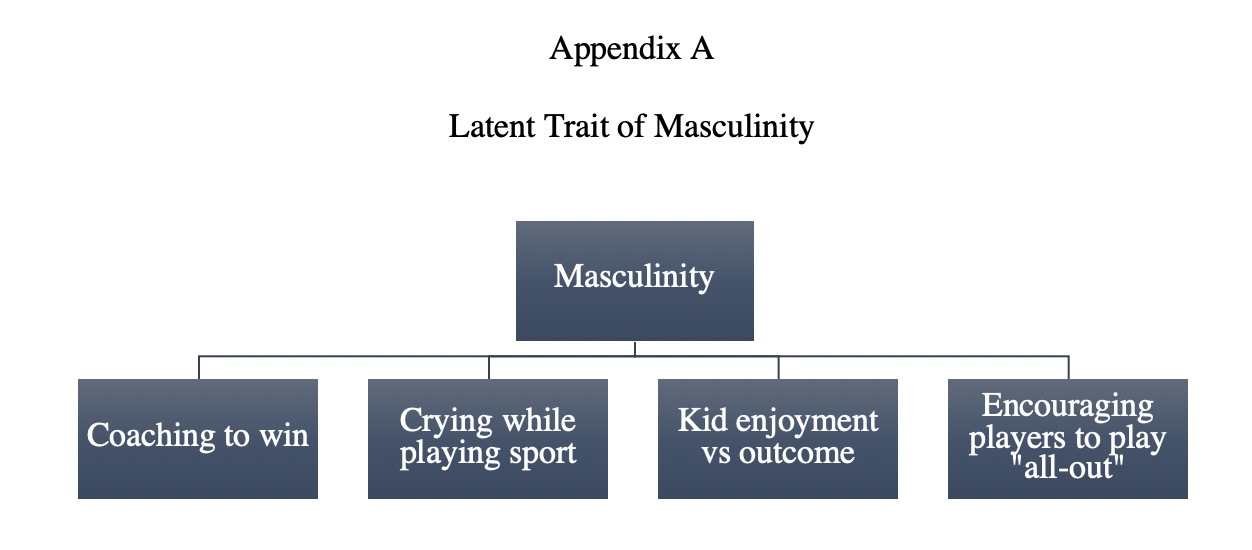

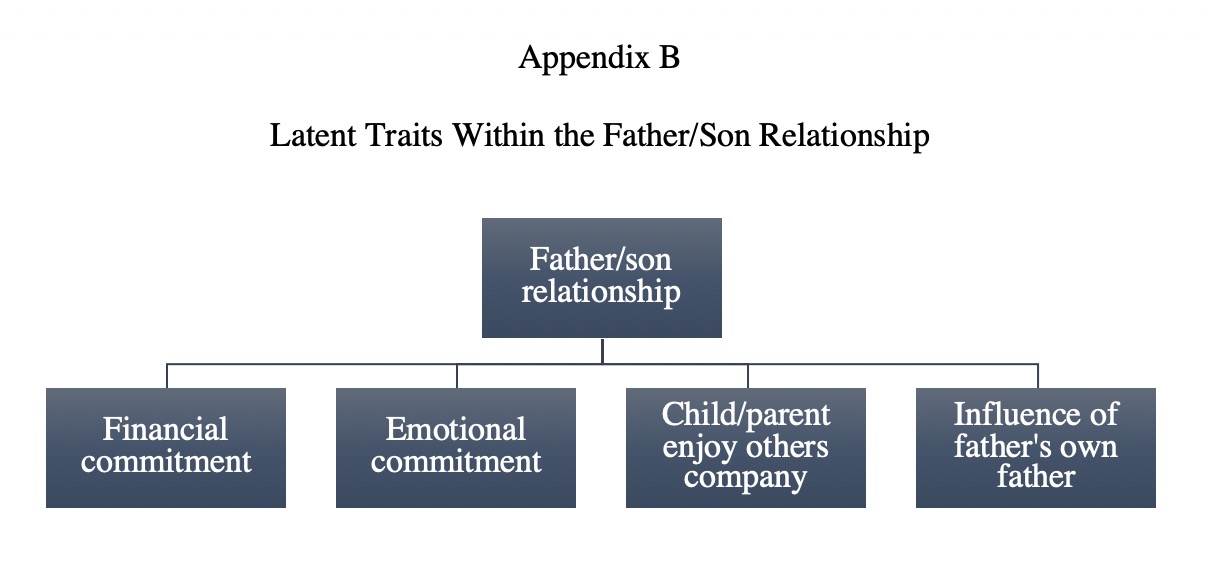

A negative relationship between orthodox masculinity and positive father-son relationships was found via a correlation test, and the results were significant at the 0.05 level. Coaching fathers who displayed more inclusive masculine traits tended to have better father-son relationships than orthodox masculine fathers. All three interviewees showed similar levels of inclusive masculinity, and all three had positive father-son relationships. Dunn, Dorsch, King, and Rothlisberger’s (2016) study on parental involvement and youth sports showed that high levels of parental involvement (both emotional and financial) could lead to a negative father-son relationship. Based on this finding, this research examined involvement and masculinity in a linear regression, hypothesizing that properly involved fathers showed more signs of inclusive masculinity than over-involved fathers. However, a weak correlation between masculinity and parental involvement was found; properly involved fathers were not more likely to show inclusive masculinity. The qualitative findings indicate that inclusive masculine coaching fathers tend to delegate their own son to another coaching father. All three qualitative interview respondents stated a preference to delegate their own son to another coach with the same team when possible; this was done by assigning coaches to handle certain positions. Respondents expressed concerns about overloading their son with at-home and on-field responsibilities, along with avoidance of bias. This emergent finding could be the basis of further research. Literature ReviewFathers often use sport to socialize their sons to masculinity (Gottzén and Kremer-Sadlik 2012). Men feel free to express masculine ideals while coaching sport, though they must decide whether these ideals are important compared to their own son’s enjoyment (Graham et al. 2016). When intersected with youth sports and parenting, masculinity takes two forms: orthodox and inclusive, as defined by Gottzén and Kremer-Sadlik (2012). Within the context of youth sports, orthodox masculinity is defined by the hegemonic ideal of fierce competition and playing to win. In this same context, inclusive masculinity is defined as ensuring the child enjoys and learns from their experience, even if winning doesn’t occur (Gottzén and Kremer-Sadlik 2012). When coaching their sons, fathers must balance support for their kid with the hegemonic ideal of fierce competition (Gottzén and Kremer-Sadlik 2012). Therefore, it is crucial for fathers to strike a balance between their ingrained masculine ideals and their son’s enjoyment of youth sports. Parental involvement (whether it be financial or emotional) also correlates with a son’s enjoyment of their sport (Dunn et al. 2016). Overly involved parents can potentially hinder a child’s enjoyment of a youth sport, as can parents with very little involvement in their son’s activities (Dunn et al. 2016). Masculinity can be conveyed generationally; the methods used by a grandfather cascade to their grandson, with the father as a liaison (Trussell and Shaw 2012). This research compliments previous research on the relationship between masculinity, sport, and parenting; this was done most prominently by Gottzén and Kremer-Sadlik (2012). Gaps exist in this field, as referenced by Dunn, Dorsch, King, and Rothlisberger (2012), and Shirani (2013).The research also considers Trussell and Shaw’s (2012) theory of involved fathering, and how this relates to masculinity and father-son relationships. Fatherhood Socialization of Masculinity through SportMen see sport as a means to develop close relationships with their sons (Gottzén and Kremer-Sadlik 2012). Fathers can practice inclusive masculinity when coaching their sons; the priority is to support their sons via positive reinforcement and effort given for the son (Gottzén and Kremer-Sadlik 2012). An alternative to this is orthodox masculinity; fathers would prioritize competitive traits and winning over supporting their sons (Gottzén and Kremer-Sadlik 2012). Graham et al. (2016) discover that many youth sports leagues train parents to be better coaches, but rarely do they focus on improving parental skills. Parenting through sport can be an effective tool; a comfort zone would have to be established between no involvement and over-involvement (Graham et al. 2016). Fathers must also balance inclusive and orthodox masculinity, a difficult-yet-attainable task. Gottzén and Kremer-Sadlik found that many fathers do not choose one type over the other, they synthesize the two types (Gottzén and Kremer-Sadlik 2012). Fathers can orient their coaching to the game’s score, while still caring for and supporting their sons (Gottzén and Kremer-Sadlik 2012). If performed correctly, this mix can be effective. Masculinity and Youth SportOne of the ways men show their masculine abilities is through sport (Shirani 2013). As men age, their physical abilities decrease, but they gain the responsibility of imparting masculinity onto their son(s). Sports are considered a masculine space; in this domain, men can feel free to express masculine ideals (Graham et al. 2016). However, because of inclusive masculinity’s rise, one can argue that orthodox and inclusive masculinity can coexist in the sports realm (Graham et al. 2016). Fathers who have aggressive outbursts can be categorized as overinvolved; these fathers become dependent on their son’s success for their own feeling of hegemonic masculinity and self-esteem (Graham et al. 2016). Financial standing can also play into masculinity, as does age (Shirani 2013). Graham et al. (2016) reiterates the importance of sport in building a father-son relationship. Recent trends show inclusive masculinity can coexist with orthodox masculinity (Graham et al. 2016). However, fathers must be careful of over-involvement in their son’s sport, a balance made harder due to the proliferation of year-round leagues (Gottzén and Kremer-Sadlik 2012; Graham et al. 2016). Parental Commitment and SportWhen a parent is more committed to the sport their child plays, the child tends to like playing the sport more. In fact, a child’s perception of parental commitment directly effects their enjoyment and commitment to their sport (Dunn et al. 2016). To create the perception of a “good” father in sports, Gottzén and Kremer-Sadlik argue that fathers should impose a balanced masculinity; this perception can decide whether a child has positive experiences in sport (Dunn et al. 2016; Gottzén and Kremer-Sadlik 2012). One way to measure parental commitment to sport is through a family’s financial investment; a higher investment correlates with greater parental pressure and decreased enjoyment for the child (Dunn et al. 2016). However, activities such as buying equipment, paying registration fees, or attending events can also create a positive connotation for the child (Kanters, Bocarro, and Casper 2008). Fathers show commitment to their sons by being involved in their sports. Since fathers see sport as an important building block to a positive father-son relationship, commitment is another way for fathers to parent through sports (Graham et al. 2016). This also shows the importance of balancing involvement and over-involvement, which factors in orthodox and inclusive masculinity (Gottzén and Kremer-Sadlik 2012; Graham et al. 2016) Theory of Involved FatheringTrussell and Shaw examine the theory of involved fathering; in a generalized sense, fathers spend time with their children in play, nurturing and socializing their kids through sport (Trussell and Shaw 2012). Fathers also see youth sport as an opportunity to improve their moral worth (Trussell and Shaw 2012). Trussell and Shaw identify involved fathering as the byproduct of an ideological shift from a “breadwinner” mentality (Trussell and Shaw 2012). The move from orthodox ideals is difficult, but a father’s own parents can help this transition. Fathers with overbearing parents may be more inclined to give a balanced parenting approach to their children (Trussell and Shaw 2012). While fathers don’t have to choose one type of masculinity over the other, the right mix between a ‘breadwinner’ mentality and inclusive masculinity is vital to the father-son relationship (Trussell and Shaw 2012; Graham et al. 2016). This makes the balance of masculinity even more important to master; to provide inclusive masculinity, fathers must move beyond cultural norms of fatherhood (Gottzén and Kremer-Sadlik 2012). Fathers with overbearing parents may be more inclined to give a balanced parenting approach to their children, eschewing orthodox masculinity (Trussell and Shaw 2012). Culturally, sports are viewed as a masculine place (Graham et al. 2016). When parenting, fathers must toe the line between the long-standing urge to over-involve themselves and to nurture their sons (Gottzén and Kremer-Sadlik 2012). The family’s attitude toward a sport correlates with how much a child enjoys the sport; when a financial commitment is involved, the size of the commitment can also drive a kid’s enjoyment levels down (Dunn et al. 2016; Kanters et al 2008). Culturally, fathers see sport as their opportunity to be involved with their sons; therefore, the masculinity line must be handled well (Gottzén and Kremer-Sadlik 2012; Trussell and Shaw 2012). In summary, theories by Gottzén and Kremer-Sadlik (2012) and Trussell and Shaw (2012) are heavily integrated in this research. The theory of inclusive and orthodox masculinity was the core of this research; several hypotheses were centered around studying the dynamic between these opposing halves of masculinity. While taking inclusive and orthodox masculinity into effect, theories by Graham et al. (2012), Kanters et al. 2008) and Shirani (2013). were considered as well. Men often show masculine traits through sports; synthesizing these theories offers a glimpse at how the added responsibilities of fatherhood interact with masculine ideals and aging (Shirani 2013). This research proposes to fill gaps Dunn et al. (2016), and Shirani (2013) reference in their work, while opening discussion regarding the roles fathers play with their own fathers and sons. Methods and ProceduresFathers use sport to promote masculinity; the purpose of this research was to examine how this effects father-son relationships. Mixed method explanatory research design was used to gather data for this study (Punch 2014). In this explanatory research, quantitative data was collected first, and qualitative data was collected to support and/or explain the quantitative data (Punch 2014). To gather quantitative data on the subject, 17 survey responses were received from fathers who have coached their sons in sports. This data was supplemented with three semi-formal intensive interviews with respondents from the quantitative surveys. Initially, 20 survey responses and four interviews were targeted, but those goals were not met due to time and resource constraints. Punch (2014) finds tangible benefits in mixed method research; the strengths of qualitative and quantitative research complement each other, and the weaknesses generally do not overlap. The population remains constant throughout both quantitative and qualitative research; fathers who have coached their sons in youth sports were interviewed. The population was therefore gender-controlled, and ranges from ages 28-67. Quantitative Research DesignThe first part of this research project was based on a quantitative survey. The surveys were conducted from January to April 2017, which gave me May 2017 to analyze collected data and conduct interviews. As with any research instrument, there were limitations. Sample size was a weakness of the research. A sample of 17 survey respondents was too small to make broad generalizations; this number was low due to financial and time constraints. Another weakness was in the survey itself. Because survey answers were predetermined, there was little room for respondent variance. This was compensated by using mixed research methods; qualitative interviews filled in information not answered by the survey. Quantitative Data CollectionThe quantitative survey was 20 questions long and took approximately 10-15 minutes to complete. The survey was hosted on Google Forms and distributed through email. The first portion of the survey collected general demographic data to analyze on race, class, gender, and age lines. The second portion asked sports-related demographic questions. These were asked to determine each respondent’s individual coaching experience. Knowing which sports and genders each father had coached, along with the father’s experience in coaching, was important to the study. The third portion asks questions to uncover latent traits within the research. By asking the questions about playing-to-win and crying in sports, the respondent’s attitudes towards masculinity can be assessed. Asking these questions reveals whether each respondent preferences winning or their son’s enjoyment of the sport coached (Gottzén and Kremer-Sadlik 2012). This represents two views of masculinity, theorized by Gottzén and Kremer-Sadlik (2012): inclusive and orthodox. Parental commitment can correlate with a child’s enjoyment of the sport; by asking questions about parental commitment and father-son relationships, the respondent’s father-son relationship was further understood (Dunn et al. 2016). Quantitative Hypotheses and VariablesGottzén and Kremer-Sadlik (2012) propose two types of masculinity: Inclusive and orthodox. By deducing each survey respondent’s type of masculinity as an independent variable, the effect both types of masculinity have on father-son relationships can be examined while considering Gottzén and Kremer-Sadlik’s (2012) theory that a mixture of both produces the best results.Orthodox masculine fathers had worse father-son relationships than inclusive masculine fathers, though a larger sample is required to draw a conclusion. Appendix A charts how the latent trait of masculinity was uncovered through survey questions. Dunn et al. (2016) found that a child’s perception of parental involvement correlates with their enjoyment of the sport. Graham et al. (2016) found that fathers who have outbursts while coaching can be categorized as overinvolved. Therefore, level of involvement was tested as an independent variable and the masculinity traits shown as a dependent variable, finding a weak correlation between type of masculinity and parental involvement levels. Trussell and Shaw (2012) found that fathers with overbearing parents tend to be more balanced fathers (between orthodox and inclusive masculinity). A father’s own father (as an independent variable) affected their likelihood of showing inclusive traits. Inclusive masculine fathers desire to raise their kids differently than how their own fathers did (Trussell and Shaw 2012). Qualitative interviews helped make the connection between inclusive coaching fathers and their own orthodox fathers, though a larger sample is necessary to draw generalizations. The effects of parental commitment and a father’s own father on a father/son relationship are mapped in Appendix B. In all hypotheses, gender and age were controlled for by only surveying male-identified adults with sons old enough to play organized sports. The hypotheses were as follows:

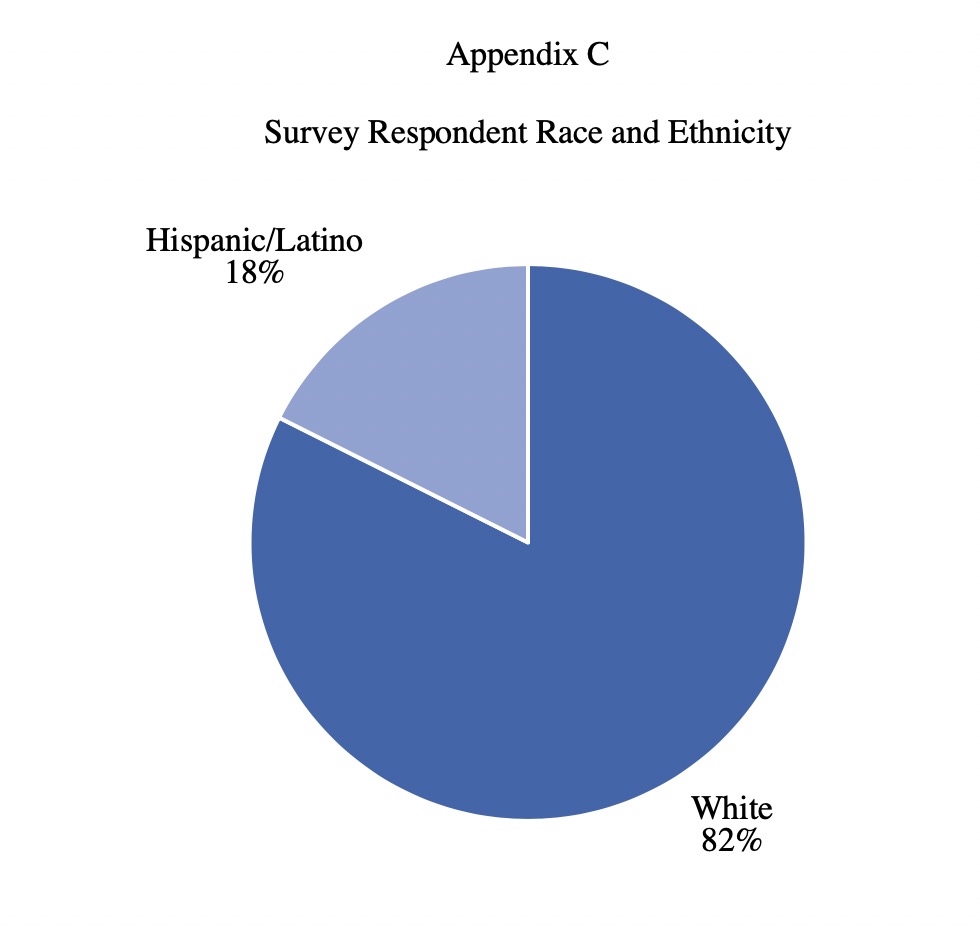

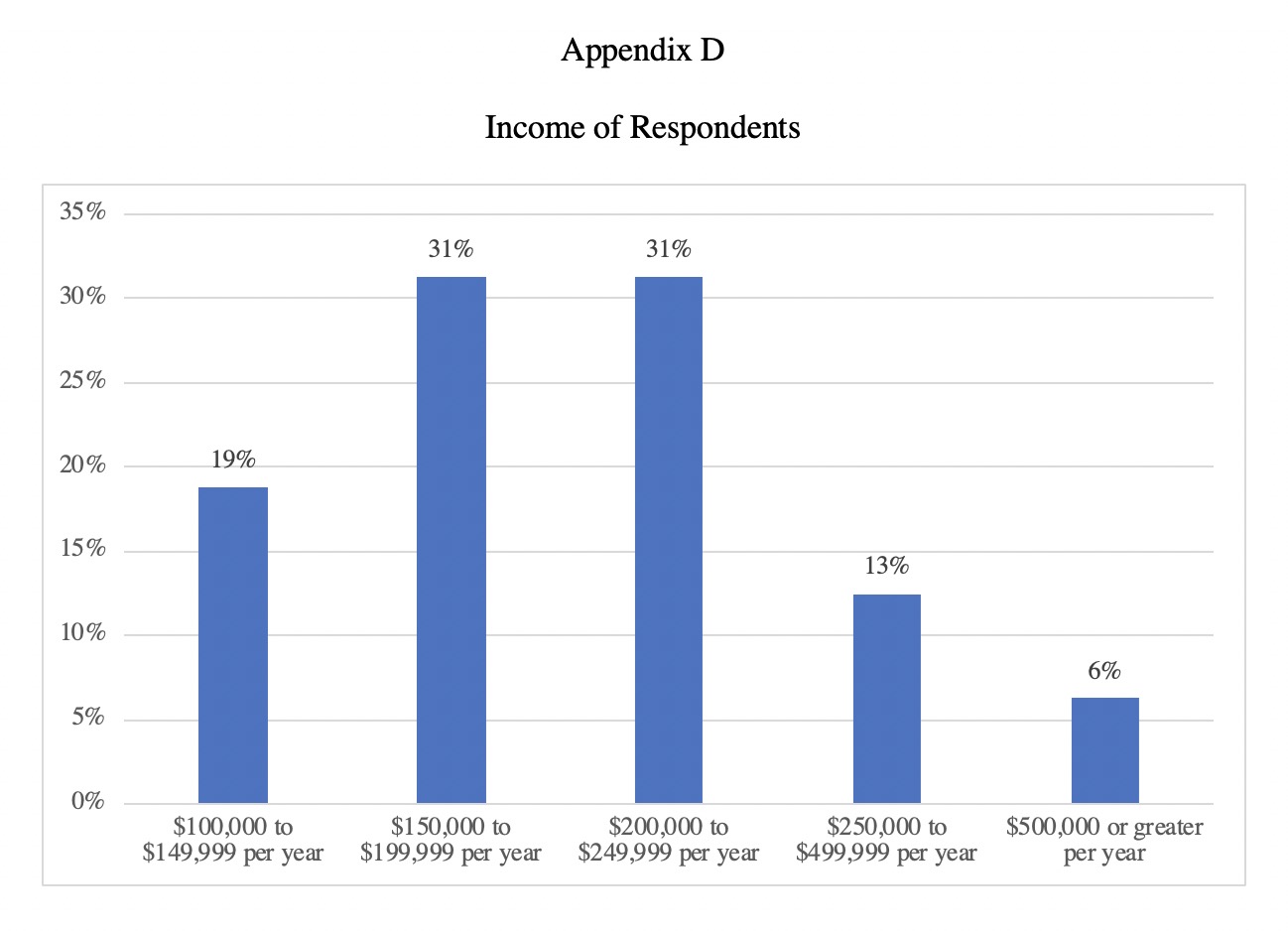

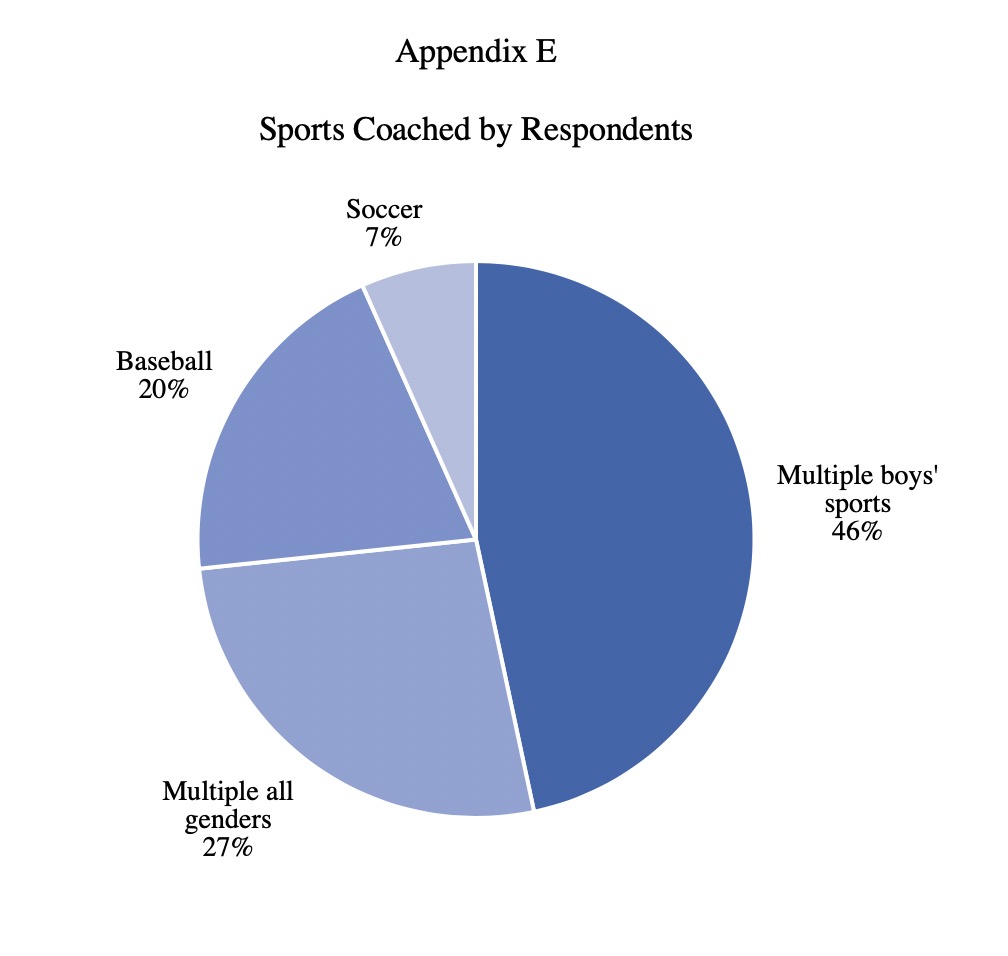

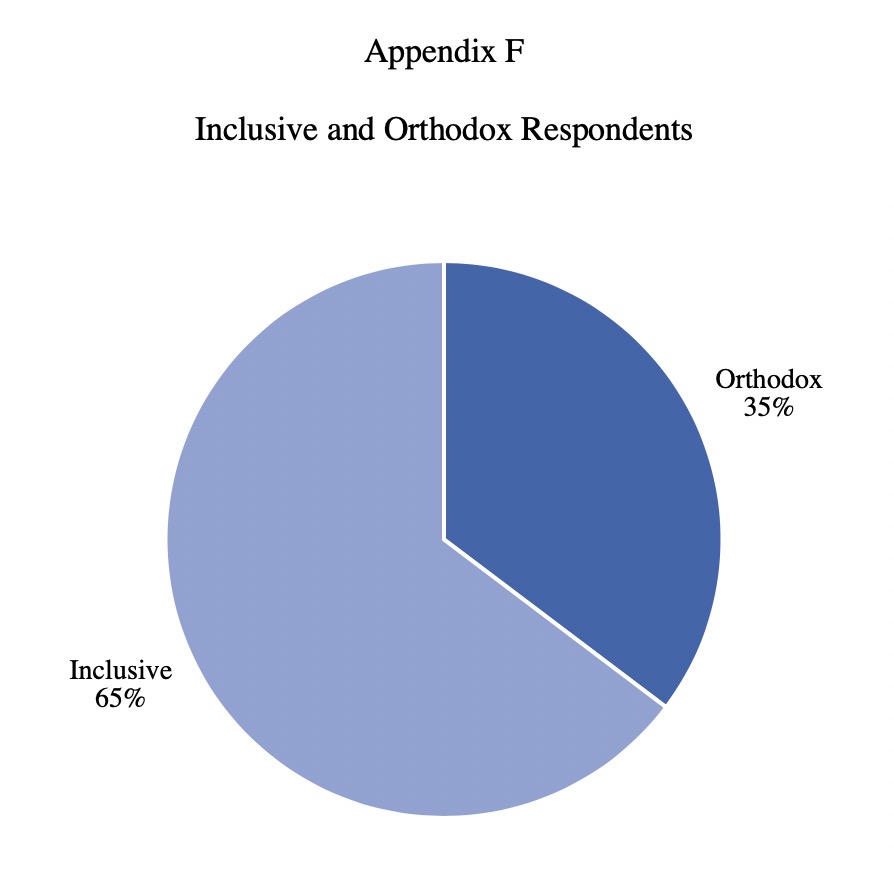

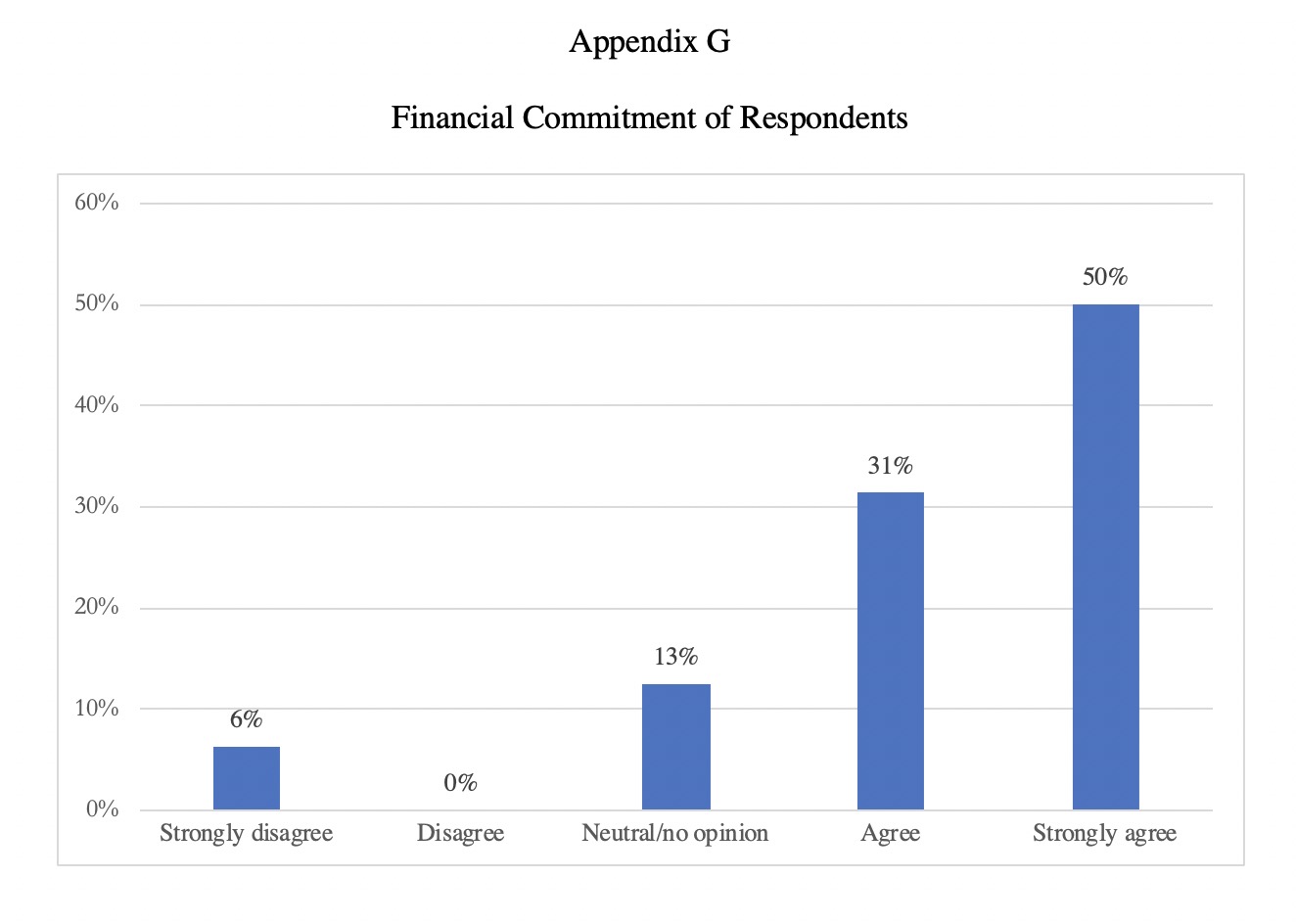

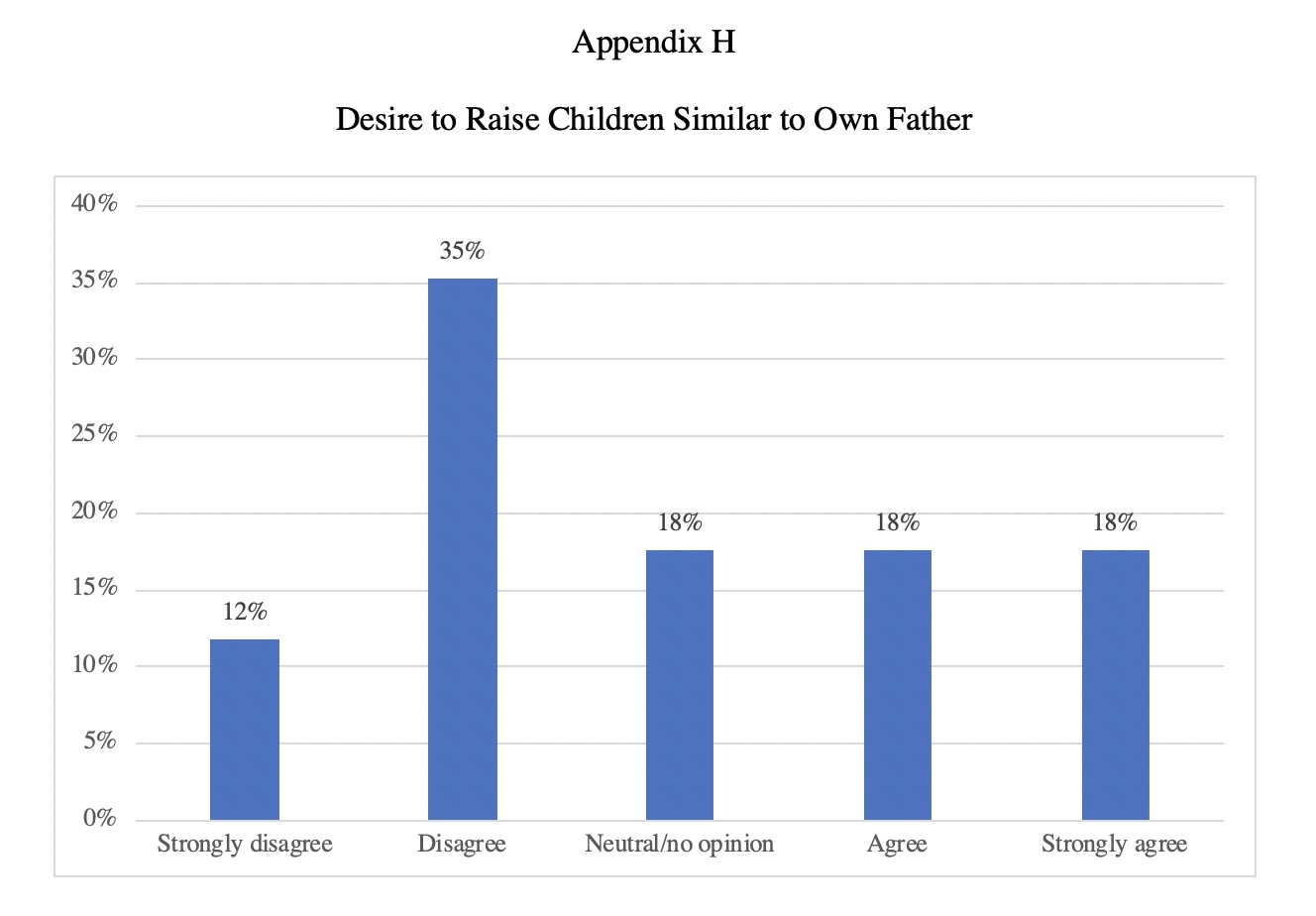

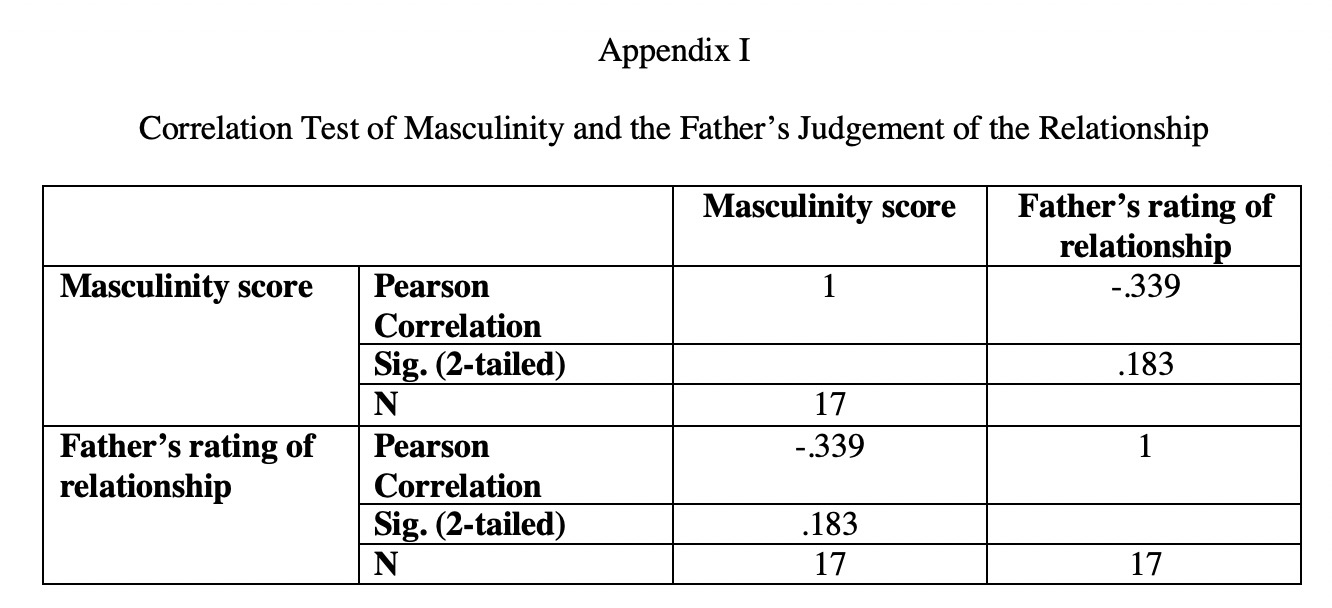

Quantitative Sampling StrategyThe population consisted of fathers (either cis-gendered or transgendered men with children) who coach or have coached their sons (either cis-gendered or transgendered boys) in youth sports; this excludes men without sons, and parents who do not identify as men. The population resides in the San Francisco Bay Area. The sample from this group is gender-controlled and ages range from 28 to 67. The sample consists of 17 fathers from this population. The Association of Bay Area Governments (2016). definition was used to identify the San Francisco Bay Area: nine counties (Alameda, Contra Costa, Marin, Napa, San Francisco, San Mateo, Santa Clara, Solano, Sonoma) encompassing 101 cities and towns. Two-stage cluster sampling was used in this research. Punch defines cluster sampling as a two-stage (or more) procedure that randomly selects clusters, then randomly selects people within each cluster. 7 Each city was defined as a cluster. The sampling frame consisted of each city in the San Francisco Bay Area; all cities had at least one youth sports league. Every city in the San Francisco Bay Area was compiled in a list, then randomly assigned a sport using a random number generator. If a city/sport combination did not exist, a new city sport/combination was selected. Cluster sampling began by randomly selecting cities from the sample frame, then contacting the randomly selected league from each city. If the league member qualifies as part of the population, they were asked to take a survey. The league member had the option to decline; if they did so, a new youth sports league was randomly selected. Because masculinity is a latent trait that cannot be deduced before surveying, and participants were already controlled for gender, stratifications were not used in quantitative sampling. This process was repeated until 17 survey respondents were received. The survey was hosted on Google Forms. As stated, the survey took approximately 10-15 minutes to complete. Due to financial and time-related constraints, a simple-random sample could not be run. Because respondents were not selected with a simple random sample, the generalizability within the sample was limited. However, cluster sampling created a viable sample for this study by randomizing the elements of the sample frame. Qualitative Research DesignSemi-structured intensive interviewing was used to gather qualitative data. Three interviews were completed in approximately 50 minutes each. Semi-structured intensive interviews gave me the best data possible; running semi-structured interviews allowed for the interviewee to show variability in their responses, which would not be possible in structured interviewing. Open-ended questions were asked, which led to more flexibility in the researcher’s role (Punch 2014). There were limitations to intensive interviewing, and some problems arose. Because the sample size was small, generalizations could not be drawn (Punch 2014). What was gathered from intensive interviewing could be a small-sample anomaly. Intensive interviewing is time-extensive, which limits the potential data bandwidth. Defending the privacy of interviewees was also important. Therefore, interviewees signed consent forms, and their names were not mentioned in this study. Qualitative Data CollectionThree fathers who have coached their sons in youth sports for at least one season were interviewed. Each of the three interviews lasted approximately 50 minutes, and each interviewee was only interviewed once. The interviews took place throughout May of 2017. Questions were progressively more personal, peaking at the second to last question and ending on a positive note for the participant. The interview respondents were given the option to skip questions they deemed were too personal, though this scenario did not arise. Questions were asked about first-hand coaching experience to catch a glimpse of how individual fathers act in coaching situations. Other points of focus were the interviewee’s father-son relationship, the interviewee’s coaching experiences, and the interviewee’s own father. The interviews were recorded with a smartphone’s microphone function. All interviewees gave consent to record them, though extensive notes would have been taken if not. Once finished, the interviews were transcribed manually. Qualitative Sampling StrategyThe qualitative population was identical to the quantitative population, consisting of fathers (cis-gendered or transgendered men) who currently coach or have coached their sons (cis-gendered or transgendered boys) in youth sports. The qualitative sample was aged from 35 to 55, approximately. To generate qualitative data, three semi-structured intensive interviews with members of the population were conducted. Each interview was approximately 50 minutes long and transcribed for easier analysis. Non-probability purposive sampling was originally planned to gather these respondents. Non-probability sampling does not use random chance; purposive sampling selects interviewees based on certain characteristics. 7 However, the responsiveness of potential participants could not be controlled. Two participants were self-selected by being more responsive to emails regarding the study; this was a convenience sample (Punch 2014). A third participant was recommended to me via an earlier interviewee; this was snowball sampling as defined by Punch (2014). Gottzén and Kremer-Sadlik define two types of masculinity: inclusive and orthodox. 4 The original plan was to pull quantitative survey respondents for qualitative interviews based on which respondents best showed orthodox and inclusive masculinity. However, the lack of correspondence from potential respondents necessitated a change away from purposive sampling and to convenience and snowball sampling. Probability sampling was not feasible for this portion of the research; generalizations cannot be made based on a sample size of three, but theory groundwork can be laid. Because of the use of convenience sampling, some level of bias has been introduced to the research. Ethical ConsiderationsTwo ethical issues arose within the study. First, participants’ data had to be kept secure. This was done by keeping physical data in a locked and hidden place, and by keeping digital data password-protected. Second, the psychological well-being of the participants had to be maintained. If any interview or survey question caused too much emotional harm, the question could’ve been skipped. Participants also held the right to stop either the interview or the survey at any time. Respect for persons was maintained by using Punch’s (2014)teleological approach to ethics; risks and benefits were weighed, and the study would not continue with a research participant if risks outweigh benefits, though this scenario did not occur. Punch’s (2014) aretaic approach was shown by ensuring beneficence; all decisions were made with virtue in mind. Justice was upheld using Punch’s (2014) theory of deontological approach; I acted in the best interests of ethical reporting and justice. American Sociological Association research guidelines were followed (Punch 2014). Any subjects who experienced adverse physical or emotional effects were allowed to quit the study at any time without penalty; this situation did not arise. Informed consent was received before starting any interview or survey. There was no deception in the research. Anonymity and confidentiality were secured through both physical and digital locks, and all identifying data has been deleted and/or redacted from the study. Because the risk was minimal and all proper precautions have been made, the benefits of this study outweighed the risk. Research Methods SummaryTo examine how fathers use sport to socialize masculinity to their sons, a 20-question quantitative survey was run, receiving 17 responses. Three semi-formal qualitative interviews were used to augment the quantitative data. While there were sample size issues, these concerns were quelled with an explanatory mixed methods approach. The survey collected thin data across 17 respondents, and the interviews obtained thick data on three interviewees. The survey uncovered information about the latent traits of masculinity and father-son relationships. Two interviewees self-selected from the pool of survey respondents, a third was selected via snowball sample from an earlier interviewee. One hypothesis postulated that inclusive masculinity leads to better father-son relationships. Another hypothesis claimed that properly involved fathers show more inclusive masculinity traits. Fathers with orthodox masculine fathers may be more likely to become inclusive masculine fathers, which correlates with what was hypothesized. ResultsThe data gathered shows prospective results for all three hypotheses. The quantitative survey sample was 17 fathers, predominantly white with upper education experience and household incomes over $100,000. The respondents have coached for an average of 6.8 years. As a group, they did not want to raise their kids similarly to how their own father raised them. They prioritized inclusive masculinity over orthodox; inclusive respondents reported having better father-son relationships than orthodox respondents. Quantitative ResultsThe respondents were predominantly white; 82.6% stated their race as such. As a collective, the respondents were well-educated and have higher-than-average incomes. This, combined with their race and ethnicity, gives evidence that the respondents have higher than average socioeconomic standing. No respondents were college-age adults; the respondent’s own education level and household income were better measures of socioeconomic status than that of their parents. The median respondent age was 48.5 years old, and all 17 respondents identify as men. The respondents primarily coach boys’ sports, and they’ve been coaching for a median amount of 8 years. In both univariate and bivariate analysis, the participants have shown signs of inclusive masculinity and proper parental involvement and may not want to raise their sons similar to how their fathers raised them. Three bivariate statistics tests were used to examine the three hypotheses. A correlation test examined masculinity traits and father-son relationships, finding that higher levels of masculinity led to less positive father-son time. A linear regression between levels of parental involvement and a father’s masculinity traits showed no correlation between the two variables, which fails to support the hypothesis. Supporting data was found regarding the potential connection between a father’s masculinity traits and a father’s own father; inclusive masculine coaching dads tend to raise their kids differently than how they were raised. Race and EthnicityAll 17 respondents listed their race and ethnicity. Fourteen respondents (82.4%) identify as White non-Hispanic, and three respondents (17.6%) listed their ethnicity as Hispanic/Latino/Spanish/etc. Sixty-seven percent of Americans are White non-Hispanic, so this sample signifies an overrepresentation of whites (Gallagher 2011). The race and ethnicity of participants is charted in Appendix C. GenderAll 17 respondents identify as men. “Woman” and “Other” were listed as choices on the survey, but none of the respondents chose these categories. The target audience was men who have coached their sons in youth sports; these results were logical and expected. No respondents withheld their answer to this question. Socioeconomic StatusThe respondents were highly educated as a group. Sixteen respondents (94.1%) graduated college with a Bachelor’s Degree or higher. Of those 16 respondents, half have a Bachelor’s Degree, five have a Master’s Degree, and three have a Ph. D., J. D., or an M. D. One respondent reported having some college experience, no respondents reported an education level lower than this. All 17 respondents reported their level of education. Sixteen of seventeen respondents reported their annual household income; no respondents report making less than $100,000 per year. Eighty-one percent make over $150,000, and half of all reporting respondents make over $200,000 per year. No respondents reported making less than $100,000 per year. This is charted in Appendix D. AgeThe median age of survey respondents was 48.50 years old, and the mean was 48.44 years. There were two modes: 44 and 45. Respondent age ranged across 39 years, from 28 to 67. Considering the target population was men with sons they have coached in youth sports, these results were logical. The 28-year-old respondent could potentially be an outlier; the mean was very slightly skewed toward the lower end of the scale due to this. One respondent did not list his age. Coaching DemographicsAs shown in Appendix E, 46.7% of respondents coached multiple sports, such as baseball, boys’ soccer, and boys’ basketball. Twenty-seven percent of participants reported coaching sports with multiple genders. The most popular single sports were baseball and soccer of any gender. Eighty-six percent reported coaching baseball, 53% reported coaching soccer. This shows a potential for seasonal bias. Many of the contacts made were through league-issued emails. While the process in selecting each league was random, there was no control over potential participant responsiveness. Because baseball and soccer were ‘in-season,’ their coaches and administrators may be more responsive to their league email than out-of-season sports like football or basketball. Two respondents declined to state what sports they coached. Respondents have coached an average of 6.8 years, and a median of 8 years. The number of years coached ranges 12 years, from 2 to 14 years. There were six modes in this dataset, each number appears twice: 2, 4, 6, 8, 9, and 12. The mean was likely skewed by the collection of modes under the median of 8. MasculinityAppendix F shows the respondents’ masculinities broken down into inclusive and orthodox masculinity. To differentiate between levels of masculinity, respondents were classified into two categories – inclusive and orthodox – based on their aforementioned masculinity score. The five-point scales cut-off was the halfway point (2.5). Eleven respondents held inclusive masculinity traits, and six respondents held orthodox masculinity traits. Relating back to the survey results, 82.4% of participants either disagreed or strongly disagreed with the idea of winning as a top priority in youth sports. One participant (5.9%) agreed with winning as a top priority; 11.8% had no opinion or were neutral. No participants withheld an answer. Only one participant felt that their kids having fun was not the top priority; the remaining 94.1% of participants either agreed or strongly agreed that their kids having fun was the top priority. Again, all 17 participants gave an answer to this question. Thirty-five percent of participants either disagreed or strongly disagreed that their kids should go ‘all-out’ to win. Another 35.3% had neutral and/or no feelings towards this question. Twenty-nine percent of participants either agreed or strongly agreed that their kids should go ‘all-out’ in search of a win. Father’s InvolvementSeventy-one percent of respondents feel they were (or were) financially committed to their kid’s sport; 50% strongly agreed. One participant did not feel he was financially committed, two others were neutral on the topic. Sixteen of seventeen respondents listed their level of financial commitment. Appendix G details the respondents’ financial commitment. Participants were asked to rate the statement, “I am (or was) financially committed to my son’s sport.” Most respondents feel they do not get too emotional when coaching (62.6%). Only one participant (6.3%) feels they get too emotional, though five (31.3%) were neutral to the question. One participant did not answer. Influence of Father’s Own FatherForty-seven percent of respondents do not want to raise their son similarly to how their own father raised them; this is graphed in Appendix H. However, 35.2% of respondents would want to raise their son similarly to how they were raised. This question was further investigated in qualitative interviews. Inclusive Masculine Fathers Enjoy Better Father-Son RelationshipsOne hypothesis claimed that coaching fathers with inclusive masculine traits would have better relationships with their sons than coaching fathers with orthodox masculine traits. To test this, a correlation test ran between level of masculinity as an independent variable, and the father’s own rating of their father-son relationship as a dependent variable. Masculinity was created as a composite rating from four survey questions; a higher masculinity score denotes orthodox masculinity traits, and a lower masculinity score denotes inclusive masculinity traits. A negative relationship between masculinity scores and the father’s own rating of the relationship (r= -.339), as shown in Appendix I. Therefore, orthodox masculinity may lead to worse father-son relationships than inclusive masculinity. This does not corroborate with Gottzén and Kremer-Sadlik’s study; they found a mixture of both inclusive and orthodox masculinity produces better father-son relationships.4 The qualitative interviews supported this quantitative finding. For example, Respondent A has inclusive masculinity traits. When coaching his youth sports team, he eschews from yelling at the kids on his team (and, by extension, his own son) when they do not do as they were told. Instead, he’ll show disappointment in his kids by voicing his concerns.

Respondent A has a positive relationship with his children, fitting Trussell and Shaw’s definition of an involved father.9

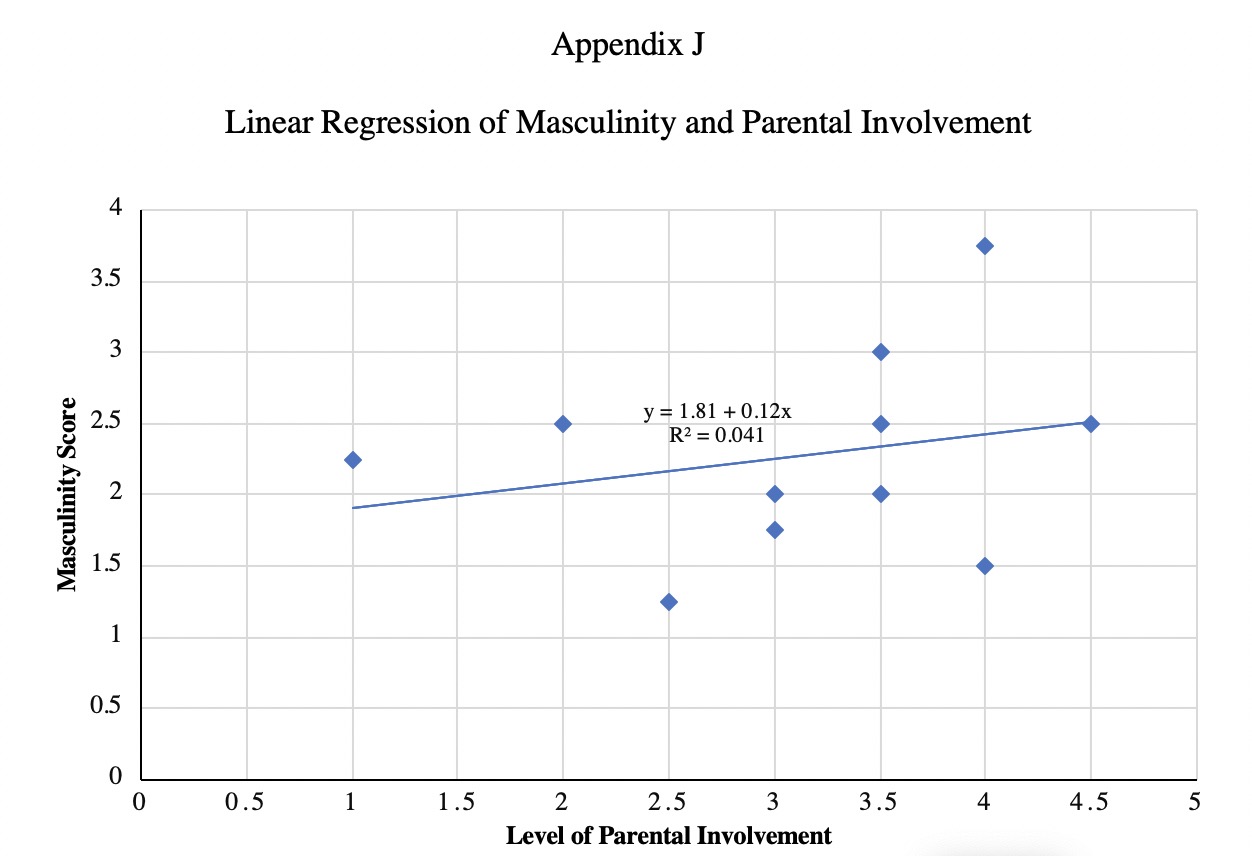

Weak Correlation Between Parental Involvement and MasculinityBased on Dunn, Dorsch, King, and Rothlisberger’s study on parental involvement and youth sports, one of the study’s hypotheses claimed that properly involved fathers were more likely to show inclusive masculinity than over-involved fathers.2 There was a weak correlation (r2= 0.04) between levels of parental involvement and masculinity score. Based on quantitative data, one can conclude the hypothesis is unlikely to be true. Further surveying would have to be done to solidify this position. To deduce this, a linear regression was run, shown in Appendix J. Involvement was created as a composite scale variable from two survey questions regarding financial and emotional involvement; this is the independent variable. Lower involvement scores denote less parental involvement, and higher involvement scores denote more parental involvement. Masculinity composite score was used as a dependent variable. As with the previous hypothesis, a higher masculinity score denotes orthodox masculinity, and a lower masculinity score denotes orthodox masculinity. Again, qualitative interviews supported the quantitative data; fathers who were more committed to their son’s sport did not show more signs of orthodox masculinity. Respondent C qualified as having inclusive masculinity and has coached three sons and two nephews across 24 years. Respondent C started this season not coaching his youngest son’s team, the first such season since his youngest son started playing youth sports. When describing the relationship he has with his youngest son, he displayed a potential correlation between high levels of involvement, a positive father-son relationship, and inclusive masculinity.

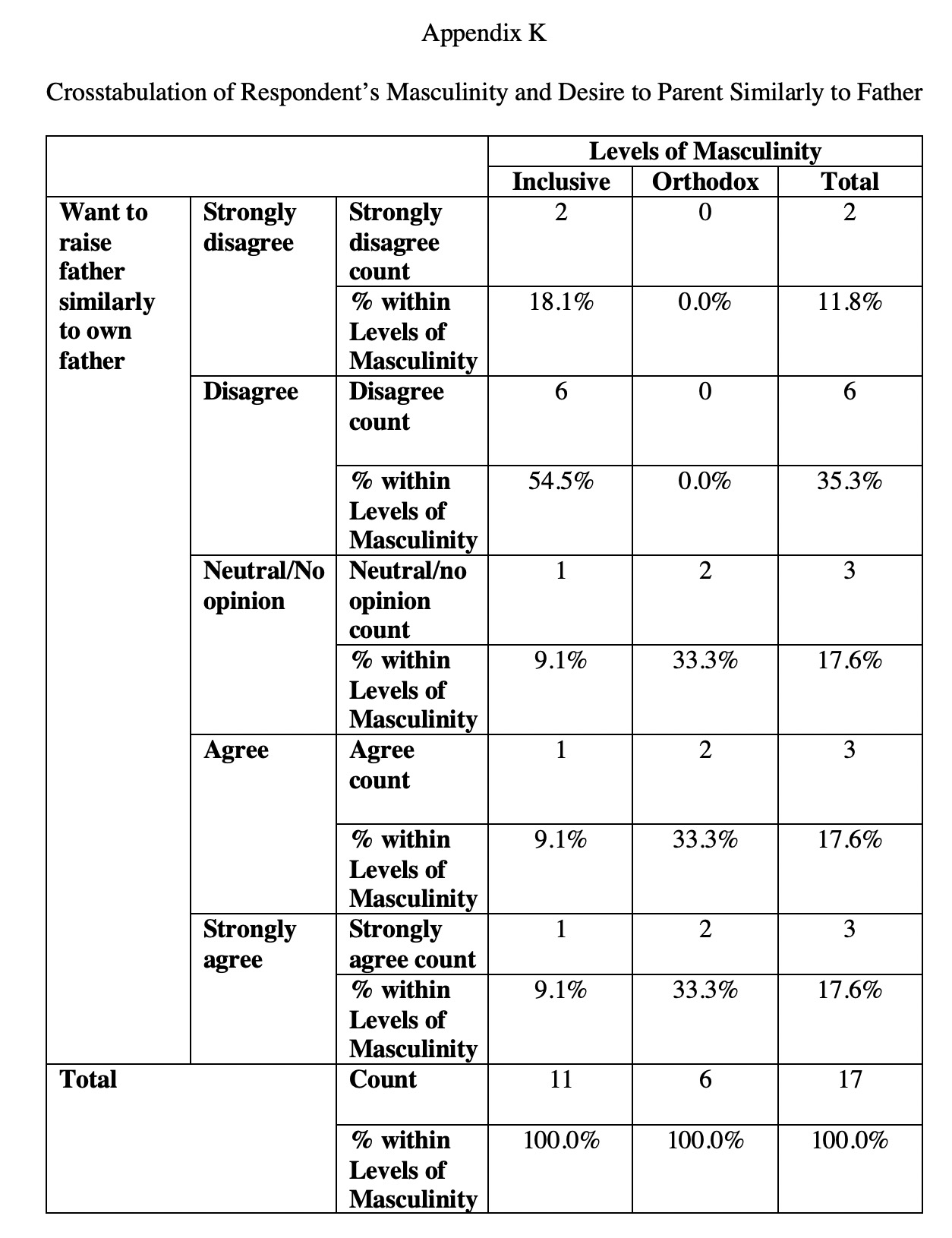

Even though Respondent C was highly involved in his son’s youth sports, he maintains inclusive masculinity and a positive father-son relationship. While further research would need to be done, there is potential for a correlation between involvement levels, inclusive masculinity, and positive father-son relationships. Orthodox Masculine Fathers Beget Inclusive Masculine SonsThe final hypothesis proposed that fathers with orthodox masculine fathers were more likely to be inclusive masculine fathers. Trussell and Shaw (2012) found that fathers with overbearing fathers themselves tended to have a balanced approach towards masculinity. 12 By testing one’s desire to parent like his own father, and testing one’s own masculinity level, the masculinity levels of both the father and his own father can be deduced. To test this hypothesis, a crosstabulation ran between the respondent’s masculinity level and the respondent’s desire to parent similarly to their own father’s parenting style. Appendix K shows the crosstabulation in full. As stated, respondents were classified into inclusive and orthodox based on masculinity score; this is derived from the quantitative survey. Of the eleven inclusive masculine fathers, eight (72.7%) either disagreed or strongly disagreed with the idea of raising their kids similarly to how their father raised them. Because these eleven respondents were inclusive masculine fathers, their fathers likely carried orthodox masculine traits. No fathers with orthodox masculine traits disagreed with the idea of raising their kids similarly to how their fathers raised them. This quantitative finding was also reflected in the qualitative interviews. Respondent B grew up on the East Coast during the 1970s. During his high school football practices, his coaches would withhold water, forcing the team to eat ice chips for hydration. While Respondent B’s father wasn’t one of his youth sports coaches, he still held “old school” views. Even with this exposure to orthodox masculinity, Respondent B shows an inclusive approach.

To Respondent B, youth sports were not solely for winning; rather, they were a way to teach dedication and coping skills to the kids at play. This supports confirmation of the hypothesis that inclusive masculinity within a sports context leads to better father-son relationships than orthodox masculinity within a sports context. Bivariate Statistics SummaryThe data gathered shows interesting evidence regarding all three hypotheses. A negative relationship between levels of masculinity and a father’s own rating of the relationship was observed; fathers with inclusive masculinity indicators tend to have better relationships with their sons. This finding does not corroborate with the theory of masculinity proposed by Gottzén and Kremer-Sadlik; they found a mixture of orthodox and inclusive masculinity would produce the best results. 4 A linear regression of masculinity and fatherly involvement uncovered a weak correlation between the two variables, which counters the proposed hypothesis. Dunn et al. (2016) theorized that high levels of parental involvement would lead to lower levels of enjoyment from their children. Lastly, inclusive masculine fathers seem less likely to raise their children similarly to how their fathers raised them. The finding certifies Trussell and Shaw’s theory that fathers with overbearing parents show fewer traits of orthodox masculinity (2012). Emergent Qualitative ResultsThree semi-formal qualitative interviews have allowed me to gather thick data on several topics; the three findings are listed below. One emergent finding has been identified: fathers often delegate their son to other coaching fathers. The reasoning was twofold; fathers want to avoid overloading their son, and they want to avoid potential bias in their coaching techniques. The other two findings are supported by existing literature on the topics of masculinity, fatherhood, and youth sports. Second, sports are considered a masculine place, and when in the domain of sports, fathers feel free to express their masculine ideals (Graham et al. 2016). As shown in the qualitative interviews, inclusive masculine fathers use youth sports as an opportunity to express their inclusive masculine ideals to the kids they coach. This builds a reciprocal relationship; the kids learn from the coach, and the coach learns about different backgrounds and perspectives from the kids. Graham et al. (2016) also theorizes that some fathers can become dependent on their son’s success for their own feelings of masculinity and self-esteem. Third, all three respondents noted parents as an issue while coaching; non-coaching parents may feel the need to reinforce their self-esteem through their own children. However, this can cause damage to the father-son relationship, or to the opportunities for growth presented by coaching youth sports. Two interview respondents were white, and a third identified as mixed White/Asian. Respondents ranged in age from mid-30s to mid-50s. All were of average to above-average socioeconomic status. Coincidentally, all three had exactly three children; though not all children were boys. Two of the three coached tackle football primarily; a third coached baseball primarily. While each respondent showed strong signs of inclusive masculinity, levels of orthodox masculinity varied across respondents. Several interesting trends arose from these interviews; three will be studied in closer focus below. Father’s Delegation of SonWhen in a head coaching positions, all three respondents prefer to delegate the duty of coaching their own son to another coach. For the respondents, this does not detract from the father-son bond that can be created through youth sports; all three reported having positive relationships with their sons. One reason coaching fathers delegate their own son to another coach was to give their son a different voice to listen to other than their own father’s. Respondent C found that the lack of differentiation between at-home and on-field responsibilities could harm the father-son relationship by overloading his son.

Respondent C delegates the responsibility of coaching his own son to another coach, and the other coach delegates the coaching of his son to Respondent C. This scenario is harder to find in baseball, as there are fewer position groups than other sports. Respondent C specializes in one particular position group, making this delegation easier to manage. Respondent C’s reasoning also shows respect for other coaching fathers involved with the team; he trusts and respects the other coaches on the team to share their knowledge with his son. Respondent C’s viewpoint was similar to Respondent A’s. The positions Respondent A watches over were different than the positions his son plays. As the head coach, Respondent A builds-in a structure so that his son can receive instruction from multiple coaches, rather than solely himself.

This structure lessens the probability of Respondent A treating his son preferentially, though the open communication lines between father, son, and non-father coach allow for father-son relationships to still exist in this context. Because of this delegation, Respondent A can maintain an inclusive masculinity; in this system, he is less likely to get mad at his own son. Respondent B, a football coach made a pact with his own son regarding his coaching. On the field, he’s the coach. Off the field, he’s dad. Like Respondent A, he coaches football, so delegation is easier than in other sports. This balance was kept because Respondent B coaches another position group.

Respondent B avoids any possible bias with his son by avoiding coaching his position. This stance was cemented by Respondent B’s desire to make his son earn playing time; there was no benefit to being the coach’s son. Respondent B’s father-son relationship was still positive, even if their on-field relationship was reported as being no deeper than a coach-player dynamic. The two haven’t made a pact to ignore each other, rather, the pact ensures all kids being coached get fair treatment. This fair treatment is a tenet of inclusive masculinity. Father-son relationships within a sports context can be positive without constant contact. Delegation is a tool coaching fathers use to avoid oversaturation in the father-son relationship; this tool has shown to be effective in practice. Although the sample size was small, there is potential for a correlation between delegated sons and positive father-son relationships. One could make the logical jump, then, that a vital part of coaching one’s own son successfully is knowing when to delegate responsibility to another coach. Growing Through CoachingCoaching fathers with inclusive masculine traits feel that youth sports can teach life lessons to the kids in their care. All three respondents expressed how virtues of discipline can be passed through coaching youth sports. Respondent B has used his position as a youth coach to teach sports as a metaphor for life experiences; playing youth sports creates early coping mechanisms for when serious issues crop up later in life.

Respondent B wants his teams to do well on-field. However, most important was that his players learn how to adapt and cope with situations that may arise in life. A youth league fumble does not equate to losing a job. However, Respondent B’s coaching style builds basic coping mechanisms that are progressively tested and improved over years, helping kids he coaches be more resilient in the face of adversity. The three respondents also felt they had experienced some degree of personal growth while coaching youth sports. Respondent A felt his years coaching youth sports have helped him understand different socioeconomic backgrounds. By coaching youth sports, he was socialized to conditions dissimilar from his own as a child.

Respondent A grew up with positive male role models in and out of youth sports. Through the years he has coached, Respondent A has become more aware of the impact lower socioeconomic status has on a kid. Therefore, he tries to be a positive role model for kids less fortunate than his own. While his son was on most teams he has coached, Respondent A can also make a strong impact on kids to whom he is unrelated. Emotionally, he has grown from a young father and former football player to a role model and youth coach. Coaching fathers feel they can help young people grow emotionally; these fathers also experience personal growth from the years they have coached. This builds a mutually beneficial relationship between coach and player; the coach imparts his knowledge onto the players, and the players expose the coaches to different mindsets and backgrounds. Coaching fathers with inclusive masculine traits often have strong positive impacts on their sons through youth sports. This relationship is important, and is the focus of this study. The relationship between coaching father and non-related player is also important, as most of the kids a father will coach are not their own; further studies could take this relationship into account. The idea of coaching fathers imparting their masculine ideals through youth sports was theorized by Graham et al (2016). This finding further examines how inclusive masculinity was imparted to kids through youth sport, while introducing the idea of the coach-player dynamic as a reciprocal relationship. Coaching Father and Other Parent RelationsRespondents A and C both discussed the phenomena of youth sport parents. Through these interviews, parents expressed the need to act for their kids; this interference can damage the coach-player relationship. Respondent A felt that handling parents was “the biggest challenge of youth sports right now.” When asked to explain further, Respondent A theorized that non-coaching parents feel empowered to speak out due to their experiences at professional sporting events.

Non-coaching parents could be inspired to speak out in defense of their child because of their attitudes towards professional sports teams. However, the goals of youth sports are vastly different than the goals of professional sports. Therefore, implementing the same mentality to both types of sport can give negative connotations of the coach to their son. This negative relationship can be damaging to the child if they see their coach as a role model. Respondent C has negative experiences with other coaches in his league. While coaching a baseball game played by eight-year-olds, an opposing coach took issue with the umpiring. He felt the umpire’s calls were unfair and decided to pull his team off the field in protest.

According to Respondent C, his first concern was not about the game itself, his first concern was on the kids of the opposing coach’s team. One could hypothesize that the opposing team’s coach had orthodox masculine traits. Respondent C felt the opposing coach was more concerned with winning than teaching life virtues. In youth sports, coaches have great influences on their players; teaching them to quit sends a non-inclusive message. Graham, Dixon, and Hazen-Swann propose that fathers can become dependent on their son’s success for their own self-esteem. 7 This, along with the reasons previously proposed, work to display the conflict between orthodox and inclusive masculinity Summary of Qualitative FindingsCoaching fathers with inclusive masculinity have learned to delegate the responsibility of coaching their own son; this was an emergent finding. Delegation allows the coaching father to avoid bias with his own son, while freeing the coach to nurture other kids on the team. The coach’s son also benefits; he can receive coaching instruction from multiple coaches rather than just his father. Delegation also helps create a mutually beneficial relationship between coaching father and non-related players. The players learn expertise from multiple sources, and the coaching fathers become more socially aware of different backgrounds. Graham et al. (2016) observed how fathers impart masculinity onto their sons. Further research into the father-son relationship would, ideally, lead to closer consideration of the coaching father-unrelated player relationship. The relationship between coaching fathers and non-coaching parents could also call for further research. If the coaches and parents in direct conflict with Respondents A and C showed overt signs of orthodox masculinity, the potential for conflict between Gottzén and Kremer-Sadlik’s (2012) orthodox and inclusive masculinity could be studied in further detail. 4 This study could also consider the effect a father’s own self-esteem has on their feelings towards masculinity, as alluded to by Graham et al. (2016). Due to sample and resource restraints, a potential study centering these points will not commence at this time. The role of delegation in a positive father-son youth sport environment could challenge the current knowledge in this field. While the idea of delegation runs in contrast to fathers spending time with their sons, the three respondents used delegation to create positive impact with their children. Because the sample size was limited, a concrete conclusion was not possible. However, with further research, one could decide whether delegation makes for better father-son relationships. DiscussionI would be remiss to not acknowledge and respect the impact women and other genders have in youth sports. While the father-son relationship through sports is often studied in academics and sepia-dipped throughout culture, mother-daughter, mother-son, and father-daughter relationships are equally as important, if not more. The biggest regret with this study was not being more inclusive. Any future researcher of these topics is strongly advised to study the relationships non-male parents and children create through this prism. Further research into the father-son relationship would need to consider a few more points in further detail. As previously noted, the relationship between coaching father and unrelated child is important to this field of study. Much of a coaching father’s job regards kids to whom he is unrelated. A study considering this in further detail could also consider the experience of playing youth sports while growing up without a father. Given more resources (both financial and time-wise), the connection between race, gender, and youth sports could be studied further. While the data gathered was adequate for this study, both the qualitative and quantitative samples displayed an overrepresentation of white fathers. This bias was partially created by the lack of correspondence from individuals in the sample frame; more baseball coaches were available. This could be because baseball was in-season during the surveying and interviewing period. However, the data gathered shows interesting findings. While the sample sizes were too small to generalize broadly, interesting trends have been illustrated. ConclusionUsing a mixed methods approach, the connections between fatherhood, masculinity, and youth sports have been studied in qualitative and quantitative lenses. Through 17 quantitative surveys, inclusive masculine fathers tended to have better relationships with their kids than orthodox masculine fathers. Through three qualitative interviews, one potential reason for this emergent finding was discovered: coaching fathers delegate their sons to other coaching fathers in order to avoid overloading their son with responsibilities, along with avoiding potential bias. Other findings were backed up by the current literature. Orthodox masculine fathers tend to beget inclusive masculine sons, as shown both in quantitative analysis and qualitative interviewing. This could potentially be true, as Trussell and Shaw (2012) theorized that overbearing fathers have sons with more inclusive masculinity traits. During qualitative interviews, respondents noted how they view youth sports as a way to impart knowledge onto the kids they coach. This finding was backed up by Graham et al. (2016), who theorized that fathers see youth sports as a way to impart masculinity onto their sons. This creates a mutually beneficial relationship; the inclusive masculine fathers were exposed to different backgrounds via the kids they coach. A potential conflict between Gottzén and Kremer-Sadlik’s (2012) inclusive and orthodox masculinity was also observed. Inclusive masculine coaching parents identified non-coaching parents as a rising problem in youth sports. Graham et al. (2016) noted that some fathers see their own self-esteem as tied with their son’s success in sport. The two primary sides of this conflict represent Gottzén and Kremer-Sadlik’s (2012) inclusive and orthodox masculinity; the coaching father wants to nurture his team, and the non-coaching parents wants their son to win and/or do well within the sport, even if the team’s success was placed in jeopardy. If a male-identifying adult is fortunate enough to become a father, they have undertaken one of the most important tasks of their life. This is a task that should not be taken lightly. However, with proper technique, coaching fathers can be positive role models to their sons through youth sports. ReferencesAssociation of Bay Area Governments. 2016. “ABAG: Overview.” Retrieved March 13, 2017. Dunn, C. R., Dorsch, T. E., King, M. Q., and Rothlisberger, K. J. (2016) The impact of family financial investment on perceived parent pressure and child enjoyment and commitment in organized youth sport. Family Relations 65(2), 287–299. Gallagher, C. A. (2011) Appendix. Rethinking the Color Line (Gallagher, C. A., Ed) 5th ed., 403–422, McGraw-Hill, New York. Gottzén, L., Kremer-Sadlik, T. (2012) Fatherhood and youth sports: a balancing act between care and expectations. Gender & Society 26(4), 639–664. Graham, J. A., Dixon, M. A., and Hazen-Swann, N. (2016) Coaching dads: understanding managerial implications of fathering through sport. ARTICLE Journal of Sport Management 30, 40-51 Kanters, M. A., Bocarro, J., and Casper, J. (2008) Supported or pressured? An examination of agreement among parents and children on parent’s role in youth sports. Journal of Sport Behavior 31(1), 64–80. Punch, K. (2014) Introduction to Social Research: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches, Sage Publications, Los Angeles. Shirani, F. (2013) The specter of the wheezy dad: masculinity, fatherhood and ageing. Sociology 47(6), 1104–1119. Trussell, D. E. and Shaw, S. M. (2012) Organized youth sport and parenting in public and private spaces. Leisure Sciences 34(5), 377–394. AppendixSuggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in Sociology |